AP UNITED STATES HISTORY

advertisement

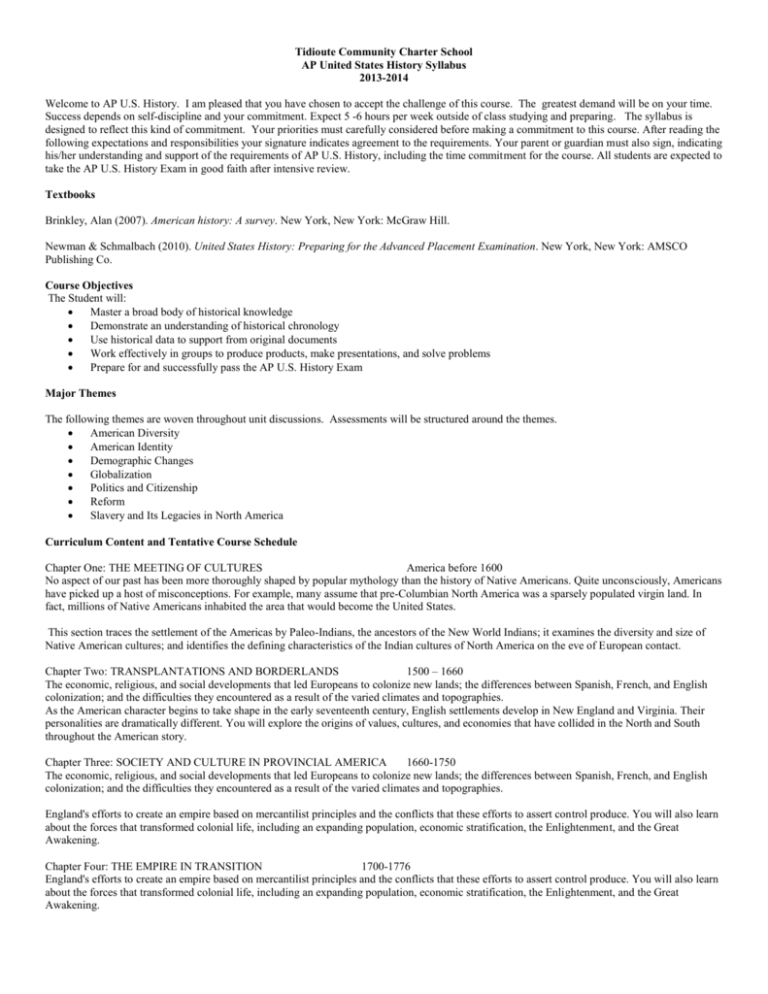

Tidioute Community Charter School AP United States History Syllabus 2013-2014 Welcome to AP U.S. History. I am pleased that you have chosen to accept the challenge of this course. The greatest demand will be on your time. Success depends on self-discipline and your commitment. Expect 5 -6 hours per week outside of class studying and preparing. The syllabus is designed to reflect this kind of commitment. Your priorities must carefully considered before making a commitment to this course. After reading the following expectations and responsibilities your signature indicates agreement to the requirements. Your parent or guardian must also sign, indicating his/her understanding and support of the requirements of AP U.S. History, including the time commitment for the course. All students are expected to take the AP U.S. History Exam in good faith after intensive review. Textbooks Brinkley, Alan (2007). American history: A survey. New York, New York: McGraw Hill. Newman & Schmalbach (2010). United States History: Preparing for the Advanced Placement Examination. New York, New York: AMSCO Publishing Co. Course Objectives The Student will: Master a broad body of historical knowledge Demonstrate an understanding of historical chronology Use historical data to support from original documents Work effectively in groups to produce products, make presentations, and solve problems Prepare for and successfully pass the AP U.S. History Exam Major Themes The following themes are woven throughout unit discussions. Assessments will be structured around the themes. American Diversity American Identity Demographic Changes Globalization Politics and Citizenship Reform Slavery and Its Legacies in North America Curriculum Content and Tentative Course Schedule Chapter One: THE MEETING OF CULTURES America before 1600 No aspect of our past has been more thoroughly shaped by popular mythology than the history of Native Americans. Quite unconsciously, Americans have picked up a host of misconceptions. For example, many assume that pre-Columbian North America was a sparsely populated virgin land. In fact, millions of Native Americans inhabited the area that would become the United States. This section traces the settlement of the Americas by Paleo-Indians, the ancestors of the New World Indians; it examines the diversity and size of Native American cultures; and identifies the defining characteristics of the Indian cultures of North America on the eve of European contact. Chapter Two: TRANSPLANTATIONS AND BORDERLANDS 1500 – 1660 The economic, religious, and social developments that led Europeans to colonize new lands; the differences between Spanish, French, and English colonization; and the difficulties they encountered as a result of the varied climates and topographies. As the American character begins to take shape in the early seventeenth century, English settlements develop in New England and Virginia. Their personalities are dramatically different. You will explore the origins of values, cultures, and economies that have collided in the North and South throughout the American story. Chapter Three: SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN PROVINCIAL AMERICA 1660-1750 The economic, religious, and social developments that led Europeans to colonize new lands; the differences between Spanish, French, and English colonization; and the difficulties they encountered as a result of the varied climates and topographies. England's efforts to create an empire based on mercantilist principles and the conflicts that these efforts to assert control produce. You will also learn about the forces that transformed colonial life, including an expanding population, economic stratification, the Enlightenment, and the Great Awakening. Chapter Four: THE EMPIRE IN TRANSITION 1700-1776 England's efforts to create an empire based on mercantilist principles and the conflicts that these efforts to assert control produce. You will also learn about the forces that transformed colonial life, including an expanding population, economic stratification, the Enlightenment, and the Great Awakening. Chapter Five: THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION 1764-1783 Examine the series of events that ruptured relations between Britain and the American colonies, and the long and bitter war that the colonists waged in order to gain independence. Chapter Six: THE CONSTITUTION AND THE NEW REPUBLIC 1776-1800 After the War for Independence, the struggle for a new system of government begins. You will loos at the creation of the Constitution of the United States. The Republic survives a series of threats to its union, and the program ends with the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson on the Fourth of July, 1826. Having won the Revolutionary war and having negotiated a favorable peace settlement, the Americans still had to establish stable governments. Between 1776 and 1789 a variety of efforts were made to realize the nation's republican ideals. New state governments were established in most states, expanding voting and office holding rights. Lawmakers let citizens decide which churches to support with their tax monies. Several states adopted bills of rights guaranteeing freedom of speech, assembly, and the press, as well as trial by jury. Western lands were opened to settlement. Educational opportunities for women increased. Most northern states either abolished slavery or adopted a gradual emancipation plan, while some southern states made it easier for slave owners to manumit individual slaves. Concern for the new nation's political stability led leading revolutionary leaders to draft a new Constitution in 1787, which worked out compromises between large and small states and between northern and southern states. Chapter Seven: THE JEFFERSONIAN ERA 1800-1815 At the dawn of the nineteenth century, the size of the United States doubles with the Louisiana Purchase. The Appalachians are no longer the barrier to American migration west; the Mississippi River becomes the country's central artery; and Jefferson's vision of an Empire of Liberty begins to take shape. As president, Thomas Jefferson sought to implement his Republican principles, including a frugal, limited government; respect for states' rights, and encouragement for agriculture. He cut military expenditures, paid off the public debt, and repealed many taxes. His most important act was the purchase of Louisiana Territory, which nearly doubled the size of the nation. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court established the principle of judicial review, which enables the courts to review the constitutionality of federal laws and invalidate acts of Congress when they conflict with the Constitution. The Jeffersonian era was marked by severe foreign policy challenges, including harassment of American shipping by North African pirates and by the British and French. In an attempt to stave off war with Britain and France, the United States attempted various forms of economic coercion. But in 1812--to protect American shipping and seamen, clear westerns lands of Indians, and preserve national honor—the county once again waged war with Britain, fighting the world's strongest power to a stalemate. Chapter Eight: VARIETIES OF AMERICAN NATIONALISM 1815-1828 The Era of Good Feelings was a period of dramatic growth and intense nationalism. The spirit of nationalism was apparent in Supreme Court decisions that established the supremacy of the federal government and expanded the powers of Congress. American interest and power in foreign policy was especially apparent in the Monroe Doctrine. Industrial development enhanced national self-sufficiency and united the nation with improved roads, canals, and river transportation. Forces for division were also at work. The financial Panic of 1819 led to the emergence of new political parties. The Missouri Crisis contributed to a growing sectional split between North and South. Chapter Nine: JACKSONIAN AMERICA 1810-1840 The period from 1820 to 1840 was a time of important political developments. Property qualifications for voting and office-holding were repealed; voting by voice was eliminated. Direct methods of selecting presidential electors, county officials, state judges, and governors replaced indirect methods. Voter participation increased. A new two-party system was replaced by the politics of deference to elites. The dominant political figure of this era was Andrew Jackson, who opened millions of acres of Indian lands to white settlement, destroyed the Second Bank of the United States, and denied the right of a state to nullify the federal tariff. Chapter Ten: AMERICA'S ECONOMIC REVOLUTION 1808-1852 After the War of 1812, the American economy grew at an astounding rate. The development of the steamboat by Robert Fulton revolutionized water travel, as did the building of canals. The construction of the Erie Canal stimulated an economic revolution that bound the grain basket of the West to the eastern and southern markets. It also unleashed a spurt of canal building. Eastern cities experimented with railroads which quickly became the chief method of moving freight. The emerging transportation revolution greatly reduced the cost of bringing goods to market, stimulating both agriculture and industry. The telegraph also stimulated development by improving communication. Eli Whitney pioneered the method of production using interchangeable parts that became the foundation of the American System of manufacture. Transportation improvements combined with market demands stimulated cash crop cultivation. Agricultural production was also transformed by the iron plow and later the mechanical thresher. Economic development contributed to the rapid growth of cities. Between 1820 and 1840, the urban population of the nation increased by 60 percent each decade. Chapter Eleven: COTTON, SLAVERY, AND THE OLD SOUTH While the North develops an industrial economy and culture, the South develops a slave culture and economy, and the great rift between the regions becomes irreversible. Students will examine the human side of the history of the mid-1800s by analyzing the lives of slave and master. Chapter Twelve: ANTEBELLUM CULTURE AND REFORM 1825-1846 The Industrial Revolution has its dark side, and the tumultuous events of the period touch off intense and often thrilling reform movements. Students will analyze the ideas and characters behind the Great Awakening, the abolitionist movement, the women's movement, and a powerful wave of religious fervor. Chapter Thirteen: THE IMPENDING CRISIS 1839-1850 Until 1821, Spain ruled the area that now includes Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. The Mexican war for independence opened the region to American economic penetration. Government explorers, traders, and trappers helped to open the West to white settlement. In the 1820s, thousands of Americans moved into Texas, and during the 1840s, thousands of pioneers headed westward toward Oregon and California , seeking land and inspired by manifest destiny, the idea that America had a special destiny to stretch across the continent. Between 1844 and 1848 the United States expanded its boundaries into Texas, the Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest . It acquired Texas by annexation; Oregon and Washington by negotiation with Britain; and Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming as a result of war with Mexico. For forty years, attempts were made to resolve conflicts between North and South. The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the northern half of the Louisiana Purchase. The acquisition of vast new territories during the 1840s reignited the question of slavery in the western territories. The Compromise of 1850 was an attempt to solve this problem by admitting California as a free state but allowing slavery in the rest of the Southwest. But the compromise included a fugitive slave law opposed by many Northerners. The Kansas-Nebraska Act proposed to solve the problem of status there by popular sovereignty. But this led to violent conflict in Kansas and the rise of the Republican party. The Dred Scott decision eliminated possible compromise solutions to the sectional conflict and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry convinced many Southerners that a majority of Northerners wanted to free the slaves and incite race war. Chapter Fourteen: THE CIVIL WAR 1861-1865 The election of a Republican president opposed to the expansion of slavery into the western territories led seven states in the lower South to secede from the Union and to establish the Confederate States of America. After Lincoln notified South Carolina’s governor that he intended to resupply Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, the Confederacy fired on the installation, leading the President to declare that an insurrection existed in the South. Early in the war, the Union succeeded in blockading Confederate harbors, and by mid-July 1862 it had divided the Confederacy in two by wresting control of Kentucky, Missouri, and much of Tennessee, as well as the Mississippi River. In the Eastern Theater in 1861 and 1862, the Confederacy stopped Union attempts to capture its capital in Richmond, Virginia. In September 1862 (at Antietam in Maryland) and July 1863 (at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania), Robert E. Lee tried and failed to provoke European powers intervention in the war by winning a victory on Northern soil. After futile pleas to the border states to free slaves voluntarily, Lincoln in the summer of 1862 decided that emancipation was a military and political necessity. The Emancipation Proclamation transformed the war from a conflict to save the Union to a war to abolish slavery. It also authorized the enlistment of African Americans. During the war Congress enacted the Homestead Act, which offered free public land to western settlers; and land grants, that supported construction of a transcontinental railroad. The government also raised the tariff, enacted the first income tax, and established a system of federally-chartered banks. Chapter Fifteen: RECONSTRUCTION AND THE NEW SOUTH 1865-1877 You will learn about President Lincoln’s and President Johnson’s plans to readmit the Confederate states to the Union; the more stringent Congressional plan; the struggle between President Johnson and Congress, including the impeachment vote; the Reconstruction era’s contributions to civil rights; the reasons for Reconstruction’s demise; and the emergence of sharecropping. Chapter Sixteen: THE CONQUEST OF THE FAR WEST 1860-1890 This chapter chronicles the construction of the transcontinental railroad; the settlement of the Great Plains; the mining, cattle, and farming frontiers; the oil industry’s birth; and popular culture’s treatment of the Western frontier. Chapter Seventeen: INDUSTRIAL SUPREMACY 1870-1910 The late 19th century saw the creation of a modern industrial economy. A national transportation and communication network was created, the corporation became the dominant form of business organization, and a managerial revolution transformed business operations. An era of intense partisanship, the Gilded Age was also an era of reform. The Civil Service Act sought to curb government corruption by requiring applicants for certain governmental jobs to take a competitive examination. The Interstate Commerce Act sought to end discrimination by railroads against small shippers and the Sherman Antitrust Act outlawed business monopolies. These were turbulent years that saw labor violence, rising racial tension, militancy among farmers, and discontent among the unemployed. Burdened by heavy debts and falling farm prices, many farmers joined the Populist Party, which called for an increase in the amount of money in circulation, government assistance to help farmers repay loans, tariff reductions, and a graduated income tax. In 1860, most Americans considered the Great Plains the “Great American Desert.” Settlement west of Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana averaged just 1 person per square mile. The only parts of the Far West that were highly settled were California and Texas. Between 1865 and the 1890s, however, Americans settled 430 million acres in the Far West--more land than during the preceding 250 years of American history. By 1893, the Census Bureau was able to claim that the entire western frontier was now occupied. The discovery of gold, silver, and other precious minerals in California in 1849, in Nevada and Colorado in the 1850s, in Idaho and Montana in 1860s, and South Dakota in the 1870s sparked an influx of prospectors and miners. The expansion of railroads and the invention of barbed wire and improvements in windmills and pumps attracted ranchers and farmers to the Great Plains in the 1860s and 1870s. This chapter examines the forces that drove Americans westward; the kinds of lives they established in the Far West; and the rise of the "West of the imagination," the popular myths that continue to exert a powerful hold on mass culture. The 250,000 Native Americans who lived on the Great Plains were confined onto reservations through renegotiation of treaties and 30 years of war. This section examines the consequences of America's westward movement for Native Americans. The 1880s and 1890s were years of unprecedented technological innovation, mass immigration, and intense political partisanship, including disputes over currency, tariffs, political corruption and patronage, and railroads and business trusts. The late 19th century saw the advent of new communication technologies, including the phonograph, the telephone, and radio; the rise of masscirculation newspapers and magazines; the growth of commercialized entertainment, as well as new sports, including basketball, bicycling, and football, and appearance of new transportation technologies, such as the automobile, electric trains and trolleys. This chapter examines the impact of and responses to industrialization among American workers, including the attempt to form labor unions despite strong opposition from many industrialists and the courts. Around the turn of the 20th century, mass immigration from eastern and southern Europe dramatically altered the population's ethnic and religious composition. Unlike earlier immigrants, who had come from Britain, Canada, Germany, Ireland, and Scandinavia, the “new immigrants” came increasingly from Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Russia. The newcomers were often Catholic or Jewish and two-thirds of them settled in cities. In this chapter you will learn about the new immigrants and the anti-immigrant reaction. Chapter Eighteen: THE AGE OF THE CITY 1876-1900 This chapter traces the changing nature of the American city in the late 19th century, the expansion of cities horizontally and vertically, the problems caused by urban growth, the depiction of cities in art and literature, and the emergence of new forms of urban entertainment. Chapter Nineteen: FROM STALEMATE TO CRISIS 1870-1900 The 1880s and 1890s were years of turbulence. Disputes erupted over labor relations, currency, tariffs, patronage, and railroads. The most momentous political conflict of the late 19th century was the farmers' revolt. Drought, plagues of grasshoppers, boll weevils, rising costs, falling prices, and high interest rates made it increasingly difficult to make a living as a farmer. Many farmers blamed railroad owners, grain elevator operators, land monopolists, commodity futures dealers, mortgage companies, merchants, bankers, and manufacturers of farm equipment for their plight. Farmers responded by organizing Granges, Farmers' Alliances, and the Populist Party. In the election of 1896, the Populists and the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan for president. Bryan’s decisive defeat inaugurated a period of Republican ascendancy, in which Republicans controlled the presidency for 24 of the next 32 years. Chapter Twenty: THE IMPERIAL REPUBLIC 1866-1917 At the turn of the 20th century, the United States became a world power. In 1898 and 1899, the United States annexed Hawaii and acquired the Philippines, Puerto Rico, parts of the Samoan islands, and other Pacific islands. Expansion raised the fateful question of whether the newly annexed peoples would receive the rights of American citizens. The Spanish American War and the acquisition of the Philippines represented both an extension of earlier expansionist impulses and a sharp departure from assumptions that had guided American foreign policy in the past. For the first time, the United States made a major strategic commitment in the Far East, acquired territory never intended for statehood, and committed itself to police actions and intervention in the Caribbean and Central America. Chapter Twenty-One: THE RISE OF PROGRESSIVISM 1900-1916 Convinced that rapid industrialization and urbanization had created serious problems and disorder, Progressives shared an optimistic vision that organized private and government action could improve society. Progressivism sought to control monopoly, build social cohesion, and promote efficiency. Muckrakers exposed social ills that Social Gospel reformers, settlement house workers, and other Progressives attacked. Meanwhile, increasing standards of training and expertise were creating a new middle class of educated professionals including some women. The Progressives tried to rationalize politics by reducing the influence of political parties in municipal and state affairs. Many of the nation's problems could be solved, some Progressives believed, if alcohol were banned, immigration were restricted, and women were allowed to vote. Educated blacks teamed with sympathetic whites to form the NAACP and began the movement that eventually wiped away Jim Crow. Other Progressives stressed the need for fundamental economic transformation through socialism or through milder forms of antitrust action and regulation. Chapter Twenty-Two: THE BATTLE FOR NATIONAL REFORM 1901-1919 Theodore Roosevelt became president as a consequence of the assassination of William McKinley, but he quickly moved to make the office his own. In many ways, Roosevelt was the preeminent progressive, yet it sometimes seemed that for him reform was more a style than a dogma. Although Roosevelt clearly envisioned a more activist national government, the shifts and contradictions embodied in his policies toward trusts, labor, and conservation reflected the complexity and diversity of progressivism. Despite being Roosevelt's hand-picked successor, President William Howard Taft managed to alienate Roosevelt and other progressive Republicans by his actions regarding tariffs, conservation, foreign policy, trusts, and other matters. In 1912, Roosevelt decided to challenge Taft for the presidency. When he failed to secure the Republican nomination, Roosevelt formed his own Progressive party. With the Republicans divided, Woodrow Wilson won the presidency. In actuality, Wilson's domestic program turned out to be much like the one Roosevelt had advocated. In the Caribbean, Wilson continued the pattern of intervention that Roosevelt and Taft had established. Chapter Twenty-Three: AMERICA AND THE GREAT WAR 1914-1929 The Associated Press ranked World War I as the 8th most important event of the 20th century. In fact, almost everything that subsequently happened occurred because of World War I: the Great Depression, World War II, the Holocaust, the Cold War, and the collapse of empires. No event better underscores the utter unpredictability of the future. Europe hadn't fought a major war for 100 years. A product of miscalculation, misunderstanding, and miscommunication, the conflict might have been averted at many points during the five weeks preceding the fighting. World War I destroyed four empires - German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Romanov - and touched off colonial revolts in the Middle East and Vietnam. WWI shattered Americans' faith in reform and moral crusades. WWI carried far-reaching consequences for the home front, including prohibition, women's suffrage, and a bitter debate over civil liberties. World War I killed more people (9 million combatants and 5 million civilians) and cost more money ($186 billion in direct costs and another $151 billion in indirect costs) than any previous war in history. Triggered by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, World War I began in August 1914 when Germany invaded Belgium and France. Several events led to U.S. intervention: the sinking of the Lusitania, a British passenger liner; unrestricted German submarine warfare; and the Zimmerman note, which revealed a German plot to provoke Mexico to war against the United States. Millions of American men were drafted, and Congress created a War Industries Board to coordinate production and a National War Labor Board to unify labor policy. The Treaty of Versailles deprived Germany of territory and forced it to pay reparations. President Wilson agreed to the treaty because it provided for the establishment of a League of Nations, but he was unable to persuade the Senate to ratify the treaty. Chapter Twenty-Four: "THE NEW ERA" 1920’s The 1920s was a decade of exciting social changes and profound cultural conflicts. For many Americans, the growth of cities, the rise of a consumer culture, the upsurge of mass entertainment, and the so-called "revolution in morals and manners" represented liberation from the restrictions of the country's Victorian past. Sexual mores, gender roles, hair styles, and dress all changed profoundly during the 1920s. But for many others, the United States seemed to be changing in undesirable ways. The result was a thinly veiled "cultural civil war," in which a pluralistic society clashed bitterly over such issues as foreign immigration, evolution, the Ku Klux Klan, prohibition, women’s roles, and race. The 1920s was the first decade to have a nickname: “Roaring 20s" or "Jazz Age." It was a decade of prosperity and dissipation, and of jazz bands, bootleggers, raccoon coats, bathtub gin, flappers, flagpole sitters, bootleggers, and marathon dancers. It was, in the popular view, the Roaring 20s, when the younger generation rebelled against traditional taboos while their elders engaged in an orgy of speculation. But the 1920s was also a decade of bitter cultural conflicts, pitting religious liberals against fundamentalists, nativists against immigrants, and rural provincials against urban cosmopolitans. Chapter Twenty-Five: THE GREAT DEPRESSION 1929-1941 This section examines why the seemingly boundless prosperity of the 1920s ended so suddenly and why the Depression lasted as long as it did. It assesses the human toll and the policies adopted to combat the crisis of the Great Depression. It devotes particular attention to the impact on African Americans, the elderly, Mexican Americans, labor, and women. In addition to assessing the ideas that informed the New Deal policies, this section examines the critics and evaluates the impact of the New Deal. The Great Depression was steeper and more protracted in the United States than in other industrialized countries. The unemployment rate rose higher and remained higher longer than in any other western country. As it deepened, the Depression had far-reaching political consequences. The Depression vastly expanded the scope and scale of the federal government and created the modern welfare state. It gave rise to a philosophy that the federal government should provide a safety net for the elderly, the jobless, the disabled, and the poor, and that the federal government was responsible for ensuring the health of the nation's economy and the welfare of its citizens. The stock market crash of October 1929 brought the economic prosperity of the 1920s to a symbolic end. For the next ten years, the United States was stalled in a deep economic depression. By 1933, unemployment had soared to 25 percent, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. Industrial production declined by 50 percent, international trade plunged 30 percent, and investment fell 98 percent. Chapter Twenty-Six: THE NEW DEAL This section examines why the prosperity of the 1920s ended so suddenly and why the Depression lasted as long as it did. It assesses the human toll and the policies adopted to combat the crisis of the Great Depression. It devotes particular attention to the impact on African Americans, the elderly, Mexican Americans, labor, and women. In addition to assessing the ideas that informed the New Deal policies, this section examines the critics and evaluates the impact of the New Deal. Chapter Twenty-Seven: THE GLOBAL CRISIS 1921-1941 In this chapter, you will learn about the war’s causes, the Holocaust, the military history of the war, the impact of the war on women and racial and ethnic minorities, the internment of Japanese Americans, and the dawn of the atomic age. Chapter Twenty-Eight: AMERICA IN A WORLD AT WAR 1942-1945 World War II killed more people, involved more nations, and cost more money than any other war in history. Altogether, 70 million people served in the armed forces during the war, and 17 million combatants died. Civilian deaths were ever greater. At least 19 million Soviet civilians, 10 million Chinese, and 6 million European Jews lost their lives during the war. World War II was truly a global war. Some 70 nations took part in the conflict, and fighting took place on the continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe, as well as on the high seas. Entire societies participated as soldiers or as war workers, while others were persecuted as victims of occupation and mass murder. World War II cost the United States a million causalities and nearly 400,000 deaths. In both domestic and foreign affairs, its consequences were farreaching. It ended the Depression, brought millions of married women into the workforce, initiated sweeping changes in the lives of the nation's minority groups, and dramatically expanded government's presence in American life. Chapter Twenty-Nine: THE COLD WAR 1945-1950 In 1945, the United States was a far different country than it subsequently became. Nearly a third of Americans lived in poverty. A third of the country's homes had no running water, two-fifths lacked flushing toilets, and three-fifths lacked central heating. More than half of the nation's farm dwellings had no electricity. Most African Americans still lived in the South, where racial segregation in schools and public accommodations were still the law. The number of immigrants was small as a result of immigration quotas enacted during the 1920s. Following World War II, the United States began an economic boom that brought unparalleled prosperity to a majority of its citizens and raised Americans expectations, breeding a belief that most economic and social problems could be solved. Among the crucial themes of this period were the struggle for equality among women and minorities, and the backlash that these struggles evoked; the growth of the suburbs, and the shift in power from the older industrial states and cities of the Northeast and upper Midwest to the South and West; and the belief that the U.S. had the economic and military power to maintain world peace and shape the behavior of other nations. Chapter Thirty: THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY 1946-1958 During the early 1970s, films like American Graffiti and television shows like “Happy Days” portrayed the 1950s as a carefree era--a decade of tailfinned Cadillacs, collegians stuffing themselves in phone booths, and innocent tranquility and static charm. In truth, the post-World War II period was an era of intense anxiety and dynamic, creative change. During the 1950s, African Americans quickened the pace of the struggle for equality by challenging segregation in court. A new youth culture emerged with its own form of music--rock ‘n' roll. Maverick sociologists, social critics, poets, and writers--conservatives as well as liberals--authored influential critiques of American society. Chapter Thirty-One: THE ORDER OF LIBERALISM 1948-1970 Between 1945 and 1954, the Vietnamese waged an anti-colonial war against France, which received $2.6 billion in financial support from the United States. The French defeat at the Dien Bien Phu was followed by a peace conference in Geneva. As a result of the conference, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam received their independence, and Vietnam was temporarily divided between an anti-Communist South and a Communist North. In 1956, South Vietnam, with American backing, refused to hold unification elections. By 1958, Communist-led guerrillas, known as the Viet Cong, had begun to battle the South Vietnamese government. To support the South's government, the United States sent in 2,000 military advisors--a number that grew to 16,300 in 1963. The military condition deteriorated, and by 1963, South Vietnam had lost the fertile Mekong Delta to the Viet Cong. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson escalated the war, commencing air strikes on North Vietnam and committing ground forces--which numbered 536,000 in 1968. The 1968 Tet Offensive by the North Vietnamese turned many Americans against the war. The next president, Richard Nixon, advocated Vietnamization, withdrawing American troops and giving South Vietnam greater responsibility for fighting the war. In 1970, Nixon attempted to slow the flow of North Vietnamese soldiers and supplies into South Vietnam by sending American forces to destroy Communist supply bases in Cambodia. This act violated Cambodian neutrality and provoked antiwar protests on the nation's college campuses. From 1968 to 1973, efforts were made to end the conflict through diplomacy. In January 1973, an agreement was reached; U.S. forces were withdrawn from Vietnam, and U.S. prisoners of war were released. In April 1975, South Vietnam surrendered to the North, and Vietnam was reunited. Chapter Thirty-Two: THE CRISIS OF AUTHORITY 1980-1988 Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter attempted to strengthen the United States' influence in foreign affairs through détente and arms control negotiations. President Reagan emphasized sharp increases in military spending and an assertive foreign policy. Reagan addressed economic stagnation and inflation through deregulation, tax cuts, reductions in government budget deficits, and the development of new computer and communication technologies. The collapse of Eastern European Communism and the Soviet Union made the United States the only superpower. Chapter Thirty-Three: FROM "THE AGE OF LIMITS" TO THE AGE OF REAGAN 1970-2000 The three decades of the 20th century were shaped by three fundamental challenges that arose in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The first was a crisis of political leadership. Public cynicism toward politicians intensified, political party discipline declined, and lobbies and special interest groups grew in power. The second challenge involved wrenching economic transformations. Economic growth slowed, productivity flagged, inflation and oil prices soared, family income stagnated, and major industries faltered in the face of foreign competition. The third challenge involved growing uncertainty over America's proper role in the world. A major challenge facing policymakers was how to preserve the nation's international prestige and influence in the face of mounting public opposition to direct overseas interventions. Homework There will be heavy reading and lots of writing. Assignments will include supplementary reading varying from a few pages to book length, research projects, presentations, oral reports, group discussions, weekly quizzes, objective and essay tests. Students will also be required to view several historical videos during the year. All work will be evaluated on its clarity, strength of analysis, historical content, presentation of argument, historical method and historiography, validity, and mechanics of English usage. Major assignments will be given in advance, with specific due date’s known far enough ahead to allow students to organize their time schedules and workload. Late assignments, though accepted, are penalized. Homework, if due a day a student is absent, is expected the day the student returns to class. Poor study habits can result in undue stress, emotional duress, poor grades and high level of frustration. AP American History is a demanding course, with homework every night. Grades Work in AP United States History is graded on a point basis. Points are totaled to determine the grade earned for each grading period There are several weighted categories; tests and historical essays (50%), homework and essential questions (30%), quizzes (15%), class participation and citizenship (5%), Of the total weighted averages, 90%=A, 80%=B, 70%=C, 60%=D. Grades will be updated and posted twice a month by computer. Missing more than 18 hours of class (excused or unexcused) a semester will result in the lowering of the academic grade. All assignments, articles and other associated AP materials are to be filed in the student’s individual resource book. Resource books will be reviewed and graded by the instructor during the semester. The key to success in this class and on the AP examination is your ability to take good notes in outline form for each assignment and topic covered. Don't throw anything away. Class Participation Student participation is required. Class criteria will focus on note taking during the lectures, in-class group assignments and classroom discussions. Consistent attendance is essential. Spring review sessions and study groups created outside of class during the year are for your benefit and are highly recommended. Times and dates will be announced in advance for the spring review sessions. Failure to bring working materials such as assignments, notes and textbook to class; disruptive behavior; working on other subjects during my class will have a negative impact on your grade. After an excused absence, it is the student's responsibility to find out what has been missed. If an absence occurs on a day when a class assignment is to be completed during the period, a different assignment may be given to students with an excused absence. Make-up tests are to be taken the week you return and are your responsibility to arrange with me. Being absent on the day before the test does not excuse you from taking the test when scheduled. Extra Credit assignments are not offered. Materials Students are to bring notebook, study guides, outlines, and articles we are working from during the week, on a daily basis. Outside course work in class is unacceptable. Failure to comply with these policies will lower the participation grade. Homework, essays, tests are to be written in ink. Papers and projects are to be typed. Students are required to maintain and effectively organize a resource book of all AP assignments, articles, study guides, notes and review material covered in this course for end of the year review. I will provide a 3-ring binder if needed. This will be extremely important to your AP Exam preparation. Academic Honesty There is an academic honesty policy at TCCS. Cheating and plagiarism will result in a zero for the assignment with no opportunity to make it up; an automatic discipline referral, and a call home. Fall and Spring Term All of the assigned readings should be completed by the end of the week during which they will be discussed. Each unit also utilizes discussions of and writing about related historiography: how interpretations of events have changed over time, how the issues of one time period have had an impact on the experiences and decisions of subsequent generations, and how such revelations of the past and continue to shape the way historians see the world today. These discussions are woven throughout the course. Examinations Weekly quizzes will be administered from each chapter. Three unit exams will be given each semester and will be a combination of objective questions and free-response essays. At the end of the first semester all students will take a comprehensive semester final. At the end of second semester, all students will receive a comprehensive take-home final consisting of ten free-response essays covering the entire year’s course. If you have any questions or want to discuss your participation in the course please do not hesitate to contact me. I am available after school by appointment. I am looking forward to a great year and am proud you have taken on this challenge. Ms. Wickert Instructor http://tccsfcs.pbworks.com awickert@tidioutecharter.com 814-484-3550