'Two Streams Flowing Together': Paul Muldoon's Inscription of

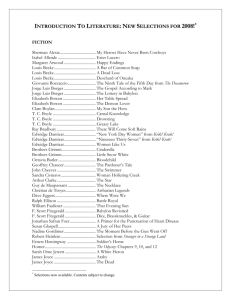

advertisement

'Two Streams Flowing Together': Paul Muldoon's Inscription of Native America. In the soliloquy which closes Paul Muldoon's libretto Shining Brow, the opera's protagonist, the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, declares, "Would that the Osage, bows in hand…might come sweeping back across the land . . ." It is a sentiment, Wright confesses, "goes back to those cowboy books/my mama gave me as a child."1 Wright's romanticism, which is undercut by a narrowly colonialist attitude towards the defeated nations of "the Ottawa, the Ojibwa, the Omaha Sioux"(SB 86), may well be intended to parody Muldoon's own interest in Native American cultures. These particular lines, however, allow a serious glimpse of both the source and the substance of Muldoon's sustained literary engagement with Native America. An adolescent passion for novels and films depicting the Wild West, not all of them sanctioned by his mother, fuelled Muldoon's avid curiosity about that far-flung 'otherworld', and was the beginning of what would develop into an informed appreciation of the historical and contemporary experience of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Events such as the release of John Ford's sympathetic 'revisionist western' Cheyenne Autumn (1964), the Indians of All Tribes' occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1967 and subsequent American Indian Movement protests in Washington and the Black Hills and, perhaps most importantly, the publication in 1970 of Dee Brown's popular Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, all made a deep impression: Muldoon sympathised, and indeed identified, with America's silenced minority. It is hardly surprising, then, that some of his earliest poems attempt to give a presence, and a voice, to Native America. 'The Indians on Alcatraz' and 'The Year of the Sloes', both published in New Weather 1 (1973) signalled the beginning of what has remained a central preoccupation, sometimes overt, more often oblique, throughout Muldoon's poetry. The significance of this pervasive 'otherness' has been debated by, among others, Jacqueline McCurry, Tim Kendall and Clair Wills, who have pointed out that Muldoon's poems about Native Americans indict colonialism in Irish, American and global contexts, as well as provide apt metaphors for the Euramerican creative artist.2 My own paper builds on those discussions, suggesting that not only does Muldoon's 'writing in' of Native America have political point and raise aesthetic issues, but that it also constitutes what the Choctaw-Cherokee-Irish theorist Louis Owens has described as "a richly hybridized dialogue"3 between cultures, a dialogue which takes place within "'frontier' space." This metaphysical frontier, as Owens defines it, is a "transcultural zone of contact," "wherein discourse is multidirectional and hybridized."4 While Owens is thinking principally about the unique position of contemporary Native American authors, his ideas are relevant to Muldoon's poetry. In an effort to tease out the possibilities within that relationship, this paper falls into two sections. The first considers Muldoon's response to Native America in a selection of shorter lyrics from New Weather through to Meeting the British. The second focuses on his assimilation of two key religious and mythological figures, the shaman and the trickster, in the later narrative poems 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants' and 'Madoc - A Mystery'. Together these approaches explore how Muldoon's inscription of Native America has developed during the past two decades, challenging and enlarging both Irish and Native American literary perspectives. 2 1. Forays into the New Frontier With the exception of John Montague5, Irish poets have tended to ignore the original inhabitants of the Americas, and to Ireland's involvement with them. So when Muldoon's first collection included one poem inspired by the Alcatraz take-over and a concluding twelve-stanza meditation dedicated to Ishi, the last known survivor of the Yahi people of southern California, it was clear that here was a poet with a decided interest in and knowledge of Native American history and culture. Characteristic of Muldoon, however, these poems harboured a 'doubleness': they were about something more, or other, than their ostensible subjects. As in later poems such as 'Meeting the British' or 'Madoc - A Mystery', the imagery and diction of 'The Indians on Alcatraz' and 'The Year of the Sloes' make it possible to read the poems as parables about the Northern Ireland 'Troubles'. The Sioux Treaty of 1868, which had effectively returned to the Sioux the Paha Sapa, the sacred Black Hills of Dakota, also granted nonreservation Indians the right to reclaim any disused government forts. In 1969 the federal prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, originally an army garrison, had been derelict for six years. The inter-tribal group which took part in the six-month occupation intended to focus public attention on a 300-year history of broken treaties, and to force the government to honour this particular aspect of the Sioux Treaty. In the event the government refused to recognise the Natives' claim, and the protestors were forcibly removed in June1971. The speaker in Muldoon's poem imagines that, like the Irish, the Indians who occupied Alcatraz "are decided/To be islanders at heart". The connection is intensified in the final stanzas: 3 After the newspaper and t.v. reports I want to be glad that Young Man Afraid Of His Horses Lives As a brilliant guerrilla fighter, The weight of his torque Worn like the moon's last quarter, Though only if he believes As I believed of his fathers, That they would not attack after dark6 The naming of Young Man Afraid Of His Horses, a Sioux warrior who fought against the Americans in the war for the Black Hills, conflates the 1967 protest with the plains peoples' resistance to Euramerican expansion in the nineteenth century. While Native warriors did employ guerrilla tactics, the phrase "guerrilla fighter," like the word "torque" - a type of body ornament worn in Celtic and Native American societies - places the poem in Irish contexts, drawing an implicit analogy between the colonisation of the Sioux in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and that of Irish, specifically Northern Irish, Catholics. What this embedded parallel emphasises is the primary, albeit divergent, significance of land to both coloniser and colonised. 'The Year of the Sloes' encourages a similarly parabolic reading. The majority of the Yahi people were massacred during the 1860s and 1870s, in the wake of the California Gold Rush. When Ishi, as he came to be known, stumbled out of the Lassen foothills in August 1911, he was terrified and starving; for the next four and a half years, until his death from tuberculosis in 1916, this so-called 'wild man' was cared 4 for, and studied, by two anthropologists at the University of California.7 In the poem, Ishi's story becomes that of two young lovers, presumably Sioux, as the narrator describes how they lose their land and their lives with the coming of the "others in blue shirts". The final stanza conjures a chilling image of genocide: In the Moon Of the Trees Popping, two snails Glittered over a dead Indian. I realised that if his brothers Could be persuaded to lie still, One beside the other Right across the Great Plains, Then perhaps something of this original Beauty would be retained. (NW 56) Muldoon has stated that this poem "was written as a direct response to Bloody Sunday, 1972, a fact that may not be immediately apparent to many readers."8 A slightly later poem, entitled 'My Father and I and Billy Two Rivers,' appears to draw a more explicit analogy between the Irish and, in this instance, the Mohawk. A closer look, however, discloses another subtle critique of the Irish contribution to global imperialism. Billy Two Rivers, a professional wrestler from the Kahnawake reserve in Quebec, toured England from 1959 to 1965, when Muldoon was a schoolboy. In the ring he wore a full feathered headdress, which he would remove to reveal a Mohawk haircut; when he lost his temper he would go into a war dance. The poem relates how father and son would attend televised broadcasts of these popular 5 "sham" wrestling matches in the local barber shop, their favoured contestant being "the Mohawk Indian." They watched him "suffer the slings and arrows/of a giant Negro who fought dirty", then return the next week to deliver: …one of his withering Tomahawk Chops to a Britisher's craw, dusting him out of the ring and into the wide-mouthed crowd like a bale of tea at the Boston Tea Party.9 In what has been described as a "cultural crosscurrent"10 a speaker whom we infer is Irish quotes Hamlet but scorns the British competitor, reinforces racial stereotypes in terminology and attitude (the honourable "Indian" is championed while the "Negro" fights dirty), and is entertained by the spectacle of 'coloureds' battering one another. Professedly sympathetic, the Euramerican speaker in fact conforms to the role of coloniser, an irony reinforced by the allusion to the Boston Tea Party. Although the rebellious colonists were disguised as Mohawks, to the Mohawk themselves the event was staged by invaders who would in turn become their oppressors. Muldoon's encoded approach to the volatile political climate in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s and subsequently has afforded the poetry its judicious, objective perspectives on 'the Troubles.' As regards his early incorporation of Native American material, though, Muldoon has conceded that "I started out in a fairly romantic way. I was interested in fairly crude parallels with the Irish situation."11 While those "crude parallels" are one effect of these and other of Muldoon's poems 6 about Native America, it could be argued that, as "My Father and I and Billy Two Rivers" shows, they are neither the primary nor the most important one. Jacqueline McCurry, in her studies of Muldoon's critique of colonialism, suggests that by "taking a global perspective [Muldoon] contrasts rather than equates the fates of American and Irish natives…" Clearly, as she concludes: …the status of Catholics in Northern Ireland as an oppressed native minority, while reprehensible, stands in sharp contrast with the status of America's natives, who, as Muldoon reminds us, were dispossessed of an entire continent.12 This crucial historical and, by extension, cultural distinction is a defining feature of Muldoon's poems. For while he highlights the destructive consequences of colonialism in a range of contexts (consider, for example, the yoking together of William of Orange, Hernan Cortes and Saul of Tarsus in 'The Centaurs'), he also makes us acutely aware of the unique experience of Native America, and of the role which the Irish have played in its political and cultural exploitation. Thus Muldoon's poems about Native America are 'double' in another sense. On the one hand, they inscribe cultures which have been consistently marginalised from Euramerican political and literary history. By introducing indigenous American history, idioms, beliefs and values, Muldoon grants Native peoples authenticity and autonomy, the poems working as a medium through which the subaltern speaks back, a Native voice is recovered. On the other hand, the poems point up Euramerican implication in, and indifference to, that absence. Without, I would argue, donning the robes of white shamanism, Muldoon -- instinctively sensitive to the importance of knowing one's 7 place -- positions himself as close to the Native as it is possible for the Euramerican writer to do, and with detached empathy makes the poems reveal our own undiscriminating acceptance of stereotypes and prejudice. In other words, Muldoon shape-shifts, shaman/trickster fashion, into the position of the colonised Native and performs what Homi Bhabha has identified as 'sly civility', or 'mimicry', the Native's subversive and parodic "refusal to satisfy the colonizer's narrative demand."13 Indeed, Bhabha's definition of mimicry is appropriate to Muldoon: …mimicry marks those moments of civil disobedience within the discipline of civility: signs of spectacular resistance. When the words of the master become the site of hybridity - the warlike sign of the native - then we may not only read between the lines, but even seek to change the often coercive reality that they so lucidly contain.14 Muldoon's resistance to the coercive realities of colonialist discourse, his fascination with or, more accurately, his dedication to, conditions of doubleness and plurality are part and parcel of his response to the social, political and historical realities of Northern Ireland. But his impulse towards the kind of hybridity Bhabha theorises is also an essential component in a clearly defined aesthetic. Indeed, the dynamic of Muldoon's engagement with Native America is perhaps most clearly summarised in his own comments in a recent radio programme: Artists may embody a multiplicity of positions, not out of selfdefence, not out of any notion of sitting on the fence, but a real regard for how people tick. And a real regard, could it be, for 8 what used to be known as Realpolitik. … The willingness to see through another's eyes and ventriloquise another's voice, to place one's self in another's place, is to give one's self over to the Zen of being a poet or painter or playwright.15 Early signs of the direction which Muldoon's interest in Native America might take are evident in the poems of New Weather. Both 'The Indians on Alcatraz' and 'The Year of the Sloes' are descriptive of Native lives from the point of view of a Euramerican speaker. However, theirs are voices which make us critically conscious of the damage done by cultural stereotyping and racial genocide. "The Indians on Alcatraz" is spoken by someone who has been following reports of the Alcatraz takeover. The poem immediately alludes to cinematic representations of Natives and, in particular, Hollywood's perpetuation of the 'vanishing race' stereotype: "The people of the shattered lances/Who seemed forever going back." (NW 39) The repetition of the phrase "as if", however, implies that these people -- the, in 1967, present-day Indians on Alcatraz -- may not conform to the Hollywood template. Far from vanishing, they are the subject of "newspaper and T.V. reports." Furthermore, the poem's lineation emphatically insures we understand that Young Man Afraid Of His Horses is not merely a name and a photograph in a history book but that he "Lives//As a brilliant guerrilla fighter." The poem's insistence on the regeneration of Native America is straightforward enough; more ambivalent is the speaker's attitude when he conveys that he wants to be glad, rather than that he is glad, that the spirit of Young Man Afraid Of His Horses is alive and well and living on Alcatraz Island. And even that desire (as opposed to the eclipsed certainty) is conditional upon Young Man believing 9 "As I believed of his fathers,/That they would not attack after dark." On one level Muldoon is clearly writing about paramilitary activity in Northern Ireland: there is a certain pride in the republicans' resistance to the British presence. However, the speaker makes plain that honour lies not in the terrorist methods of the post-1960s IRA, but in the 'daylight' negotiations of the old IRA. More complex is the speaker's final assertion that he can be glad Young Man lives only if he conforms to what by the 1960s had become a cinematic convention of the Hollywood western. Traditionally, some Natives would not have attacked after dark for fear that if they were killed their souls would not achieve an afterlife. But as the Plains Wars escalated, the period during which most Hollywood westerns were set, it was a practice which of necessity had become less frequently observed. In the course of the poem the speaker is sympathetic towards Native Americans, yet in the end accepts the stereotype and requires that Young Man and his comrades internalise it too. In this way he identifies himself with the perpetrators of the racial and cultural genocide which has all but eradicated the Natives. It is a bold move, one which invites Muldoon's Euramerican readership to identify with the same voice which, ultimately, castigates them. 'The Year of the Sloes' adopts a similar trajectory, tracing as it does the fate of the two young lovers (themselves a figurative 'doubling' or 'twinning' of the singular Ishi) in a effectively stylised idiom borrowed from Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: In the Moon Of Frost in the Tepees, There were two stars 10 That got free. They yawned and stretched To white hides, One cutting a slit In the wall of itself And stepping out into the night. (NW 53) The poem's structure, each stanza corresponding to a moon, or month, in a hierophantic reading of the natural year, as well as its stilted rhythms and iconographic imagery, establish the voice as belonging to a Native speaker, most likely an oral storyteller. It comes as a surprise, then, when in the final stanzas the third person account flips into first person: coloniser has usurped both the land and the voice of the colonised, and we are left with that horrific, yet paradoxically beautiful, picture of appropriation and extermination. Clair Wills has suggested that "The poem addresses the culpability of poetic language as it buries events and emotions in order to transform them into art."16 Yet if the poet contemplates his own guilt in the aestheticisation of violence, his skillful manipulation of language wins our sympathy for the Native voice, the range of joys and sufferings it expresses, only to have us admit, ultimately, our complicity with the source of its erasure. While one might be tempted to accuse Muldoon of reinforcing the vanishing race stereotype in these and subsequent poems -- for instance, the Natives who appear in 'The More A Man Has The More A Man Wants', 'Madoc' or 'Meeting the British' all seem headed, like the riders in Edward Curtis' famous photograph, into the final sunset -- the cumulative effect of a cache of Native words, figures and historical events is a declaration not of absence, but of presence. From the rewriting of Crazy 11 Horse's war cry as "Any day now would be good to die" (NW 56) through the list of New World commodities on offer in Golightly's Emporium, which includes "A skein of pemmican…Squashes, pumpkins,/An armful of pelts", 17 to the visions and speeches of Joseph Brant, Handsome Lake, Red Jacket and Cornplanter which pepper 'Madoc - A Mystery', Muldoon foregrounds a history and culture that for most Euramerican readers has been largely obscured. Encountering one narrator whose grandmother was part Cree and whose father chooses 'going native' in Brazil, Bolivia or the Argentine to staying put in Northern Ireland or New York, and another who listens to a bobolink scream in "Gaelakota" and hears "Oglalagalagool's/cackackle Kiowa's", we are steadily familiarised with what is less a parallel universe than a fully integrated one. By the time we arrive at 'The Birth' in The Annals of Chile, the navajo rugs and peyote buttons, Chester Callman's Kwakiutl false-face and glib and Montezuma's daughter's obsidian knife are all part of "the general hubbub/of inkies and jennets and Kickapoos with their lemniscs" into which the poet's daughter, Dorothy Aoife Korelitz Muldoon, arrives.18 The terrain which Muldoon negotiates in these poems is both linguistic and political; in its collision of Native and Euramerican cultures it occupies Owens' frontier zone, that "transcultural space" which is "always vulnerable, easily penetrated, and in endless flux," its vitality sourced in that very instability.19 While the poetry may enact a pluralist vision of cultural hybridity, and thereby proffers an alternative to the dualistic thinking that besets Ulster, it remains consistently critical of colonisation. After New Weather, virtually all of Muldoon's poems which look to Native America have as their baseline the stark contrasts between Native and Euramerican world views, concerning themselves, however obliquely, with the damages of the colonial project. What is notable about them is the 12 poet's effort not just to describe but to actually get inside Native experience, to look at the world from the other's perspective. For instance 'Sir Walter', which imagines Raleigh (who sponsored settlements but in fact never set foot in the Virginias) arriving in the New World: I picture the hands of a seaman Outstretched to say what they mean To an Indian. Freckled and veined As tobacco leaves, and not yet cured.20 Here the reader is invited, albeit with the benefit of hindsight, to ponder the significance of the Englishman's gestures, his sign language, from the point of view of a local who may be Powhatan, Croatan or Occaneechi. Raleigh's hands are outstretched and therefore friendly; figured as tobacco leaves, a substance that would have been familiar to the Natives, they appear unthreatening. That the hands are "not yet cured" suggests the Native's understanding that the newcomers are 'green', in need of the guidance and support which they willingly gave them during their first years in the Virginia colonies. But the phrase also carries meanings which the Native cannot know. Raleigh's participation the Irish campaign has left him no more cured of his acquisitive desire for land and personal glory than his successors will be of the deadly smallpox virus which in short time would decimate the indigenous population. In its attention to Native perceptions, and its conflation of them with Euramerican perspectives (the speaker, in the end, seems able to contain both), 'Sir Walter' prefigures 'Promises, Promises', in which the central stanza consists of a cognate reverie: "I am with Raleigh, near the Atlantic,/Where we have built a 13 stockade/Around our little colony."21 Marooned "On a farm in North Carolina" and pining for his beloved in Bayswater, the speaker becomes one of "eighty souls" abandoned by Raleigh on Roanoke Island. In fact the settlement was headed by Governor John White, who in 1587 returned to England for supplies. When he came back three years later, the settlers had vanished. The fate of the Roanoke colony remains a mystery, though one theory has it that they assimilated with the friendly Native population. 'Promises, Promises' develops this notion (and anticipates Muldoon's subsequent exploration of the Madoc legend), having Raleigh return to a mere "glimpse" of his former countrymen: He will return, years afterwards, To wonder where and why We might have altogether disappeared, Only to glimpse us here and there As one fair strand in her braid, The blue in an Indian girl's dead eye. (WBL 24) The stanza's final image, like the voice that speaks it, is a hybrid; blonde hair and blue iris are testament to the transformation of coloniser into colonised, the double metamorphosis of pining poet into exiled Englishman into mixedblood American. In terms of voice 'Promises, Promises' is the inverse of 'The Year of the Sloes' since here the move is towards, rather than away from, Native articulation. What unsettles this 'poem within a poem', and invests the framing stanzas with more than a hint of uncertainty, is the polysemeous "dead eye." Is the girl dead, or is it just her eye that 14 does not function? Does the image impact the full weight of the genocide to come, or does it suggest a freakish aberration, the consequence of genetic incompatibility? Whichever way we read it, the union of Native and Euramerican results in sorrow and loss. Alternatively, though, we might see the Indian girl with her streak of European wile as a 'dead eye' in the sense of a 'good shot', an enhanced version of Native or Euramerican alone who is well able to deal with the promises and betrayals of returning governors. In either case, one of the poem's achievements is that it concentrates our focus on that fusion of worlds, causing us to enter in and listen carefully to the hybridized dialogue of frontier space. Whereas the long poems 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants' and 'Madoc - A Mystery' are Muldoon's most expansive responses to Native America, two poems at the centre of Meeting the British, 'The Lass of Aughrim' and the title poem, constitute his most concentrated engagement. 'The Lass of Aughrim' borrows its title from an Irish ballad which tells of a young woman seduced then abandoned by Lord Gregory. For many readers the immediate resonance is with Joyce's short story 'The Dead', in which Gretta Conroy sings the song while remembering her lost love Michael Furey. Although Joyce's work is a provocative subtext, Muldoon upsets expectations of a parallel performance. Travelling by outboard motorboat "On a tributary of the Amazon", the speaker hears the music played on an Indian boy's flute. His delight at encountering the familiar tune perhaps disperses with the Native guide's comment: 'He hopes,' Jesus explains, 'to charm fish from the water 15 on what was the tibia of a priest from a long-abandoned Mission.'22 In a parable that echoes Conrad's Heart of Darkness, the Irish lament, incongruously taught to Brazilian Natives by Christian missionaries, perpetuates the legacy of the colonisers at the same time as it subversively celebrates the fact that they are now 'dead and gone'. The song has been transformed into an instrument of magic, a metamorphosis in keeping with the recycling of the priest's tibia as a flute and Christ's name as a common Spanish-American appellation. Things are recontextualised, assimilated and made other than they were. Rather than perpetuating colonial influence, the legacy is absorbed and hybridised. While the poem makes its indictment of colonialism, principally through the speaker's own repetition of the conquistadors' and missionaries' penetration of South America, it also allows for a postcolonial reclamation of voice and self-identification. Although Jesus must communicate in English, half the poem is spoken by him, and the appropriated strains of The Lass of Aughrim now belong to the Indian boy with his bone flute. More completely than any of the previous poems, this pithy lyric enters into the multidirectional, hybridized dicourse of Owens' frontier space. 'Meeting the British' takes us deeper still into that vital territory. Contrary to the expectations set up by the title of an encounter between Irish and English, the poem is set in North America in 1763, in the aftermath of the French and Indian War. Allies of the defeated French, the nations of the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley united under the Ottawa chief Pontiac and, in what came to be known as Pontiac's Rebellion, attempted 16 to drive back the victorious British and the tide of settlers flooding across the Alleghenies. Panicked by Pontiac's swift taking of British holdings, the British command devised an insidious offensive. Sir Jeffrey Amherst, Commander of the British forces, wrote to Colonel Henry Bouquet, "Could it not be contrived to send the Small Pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians?", to which Bouquet responded, "I will try to innoculate the [Indians] with some blankets that may fall in their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself."23 'Meeting the British' is the first and only of Muldoon's poems to be spoken entirely by a Native, an Ottawa, possibly Pontiac himself. Although the poem is, necessarily, scripted in English, we should imagine it as interior monologue recollected (perhaps, even, from beyond the grave) in the speaker's own language, breaking only briefly into French: We met the British in the dead of winter. The sky was lavender and the snow lavender-blue. I could hear, far below, the sound of two streams coming together (both were frozen over) and, no less strange, myself calling out in French 17 across that forestclearing. Neither General Jeffrey Amherst nor Colonel Henry Bouquet could stomach our willow-tobacco. As for the unusual scent when the Colonel shook out his hand- kerchief: C'est la lavande, une fleur mauve comme le ciel. They gave us six fishooks and two blankets embroidered with smallpox. (MB 16) The ironic delicacy of those fishhooks and embroidered blankets, combined with the Colonel's beguiling lavender-scented "hand-kerchief" shaken out not in a gesture of friendship or surrender, but as a calculated measure of self-protection, is Muldoon's sharpest indictment of the devastating effects of European colonisation on Native America. An initial reading of the poem might suggest an easy analogy between the vicitimization of Natives and Irish by the British, but historical context complicates that interpretation. As Jacqueline McCurry has shown, the decisive role played by Americans of Irish and Scots-Irish descent in the suppression of the Native nations during the French and Indian War equates them less with Pontiac and his allies than with the British. As McCurry writes, "The natives of America and, by implication, the 18 natives of Ireland, are yoked together in a way that shatters political preconceptions."24 Understood in this light, the title 'Meeting the British', like Muldoon's previous poems about Native America, takes on grim, self-accusatory meaning. That said, we are well advised to bear in mind Tim Kendall's observation that the poem is "at once distanced from the recent history of Northern Ireland and parallel to it,"25as well as Muldoon's statement that "It would be naïve of me to say that there's no parallel."26 The poem's anti-colonial lament, along with its funereal imagery -- "the dead of winter," the lavender-blue snow and iced-up streams, the incipient smallpox -would seem to imply that the speaker is at a dead end, he and his people destined for extinction. Again, Curtis' 'The Vanishing Race' flashes up. The speaker's present and prescient voice, however, pulls in the opposite direction. Not only is he acutely conscious of the sensual nuances of his environment, noting as he does the unusual correspondence between the scent on Bouquet's handkerchief and the colour shared by sky and snow, the sound of water running below ice and the strangeness of his own voice speaking French, the contrasting textures of fishhooks and blankets, but he also has an uncanny, shamanistic knowledge of the British intent. The icy stasis of the moment allegorises the speaker's inability to alter the course of history; aware that this 'gift' will seal his people's fate, he is compelled to accept it. Despite the surrounding hinterland, there is an oppressive claustrophobia in this tableau that is relieved only by "the sound of two streams coming together". Clair Wills has argued that in this poem "the consequences of trust and openness are devastating."27 On one level this is obviously the case. However, although the British and the Natives are divided by "that forest-/clearing", speak different languages and cannot "stomach" one another's ways, what the speaker hears "far below" the frozen surface is something we 19 can also hear in Muldoon's poem: the hybridised voice of the Native enunciating in a new "frontier space." Here, the Native who thinks Ottawa, whose words we read in English and who speaks in the mediating language of French, assumes a postcolonial presence that gives voice to the margins. Through this dialogue between cultures Muldoon symbolically expresses a human universal that transcends difference; having listened in, there is no returning to the silence. 2. Shamans and Tricksters 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants' and 'Madoc - A Mystery', two of Muldoon's major works to date, are far from silent on the subject of Native America. Both long poems contain Native characters, a catalogue of Native cultural and linguistic references, and a scathing indictment of Euramerican, specifically Irish American, treatment of Native peoples. These aspects of the poems have been examined in detail elsewhere;28 my intent in this section of the paper is to consider how Muldoon's incorporation of the shaman and the trickster in these pieces contributes to the "hybridized dialogue" which I have suggested is present in the shorter lyrics. The shaman and the trickster are pivotal figures in the majority of Native American societies, with variations in their nature and function determined by the cultural imperatives of each group. Whereas the shaman is embodied in an actual human being, sometimes a woman but usually a man, who fulfils the roles of priest, doctor and psychiatrist, the trickster in his different guises -- coyote, raven, hare or Iktome the spider -- is a creature of fiction, his by turns generous and self-interested actions providing one of the key components in Native myths and legends. On various 20 occasions Muldoon has invoked the shaman and the trickster as 'fitting emblems' for the poet, and a brief look at their respective positions reveals why the association is apposite. Shamans (a word, incidentally, of Sanskrit - srama, meaning 'religious practice' - via Russian - Tungus saman - origin and therefore not the term used by most Native American peoples) are intermediaries between material and spiritual worlds; they gain direct experience of sacred knowledge through dreams or visions, enlist the aid of spirit helpers to assist in cures, and in trance states can shape-shift, travel after souls, recover lost objects and diagnose and cure illness. Abuse of these powers renders them feared witches.29 The trickster is both culture hero and rebellious outsider. While as Promethean transformer he helps to create the world for humans, as foolish, bungling trickster he messes it up. He is, in essence, the mythical embodiment of human nature itself, acting out our achievements and our failures. As critic Larry Ellis has put it, "The Native American Trickster is a figure who defies category….[he] thrives in a region of in-betweeness where ambiguity [and] paradox are the natural order." 30 In many ways he is the opposite and the double of the shaman; his bad behaviour frequently parodies the good work of the shaman, and he can be seen as representing a humanist as opposed to the shaman's magico-religious sensibility.31 But what the shaman and the trickster share, and what they share with the poet, is their liminal position as mediators between human and supernatural realms. Clearly what has attracted Muldoon to the shaman, from early poems such as 'The Cure for Warts', 'Seanchas' and 'Party Piece' through the drug-induced hallucinations of 'Immrama' and Quoof to the vision-quests which inform 'Madoc - A Mystery', is the figure's proximity to the perceived role of the poet as seer and spiritual legislator, revealer and healer and skilled satirist. At the same time, Muldoon is wary of grand claims for the powers of poetry or the poet; for instance, in 'Glanders' 21 and 'Yggdrasill' he draws attention to the thin line between the shaman and the 'sham man'. The trickster has made fewer appearances than the shaman in Muldoon's poetry, but his presence in 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants' enables a powerful ethical interrogation, while more generally his ambiguous status as maker and iconoclast, inhabitant of borders and borderlands, and his playful, insatiably curious approach to the world contains not just Muldoon's ideas about the role of the poet, but his poetic style as well. Like the shape-shifting trickster, the poet executes linguistic metamorphoses which extend the possibilities of language in startlingly inventive ways. These are not new observations; several critics have noted the fit between these figures and Muldoon's aesthetics. But once again I would argue that there is more than simple appropriation going on here, something other than the use of one culture to talk about another. Muldoon's incorporation of the shaman and the trickster extends and intensifies the inscription of Native America which I have been tracing through the earlier poems. By focussing our attention on these key Native personalities, requiring us to discover their significance both within his poems and in their own right, Muldoon continues to give Native America a presence, and in ethnohistorical terms a remarkably authentic one, within Euramerican literary discourse. And it is through that presence, that "willingness to see through another's eyes and ventriloquise another's voice," that Muldoon is able to make his most emphatic statement about the importance of cultural hybridity and the energy freed up in frontier space. To return to Homi Bhabha for a moment, Muldoon's playful yet wholly serious form of mimicry, his attempt to regard, and to have us regard, the world from a Native American point of view, is more central to his aesthetic and ethical vision than is often acknowledged. 22 The epigraph to Quoof is taken from the Danish-Eskimo explorer-ethnologist Knud Rasmussen's The Netsilik Eskimos, and tells of a female shaman who is so powerful she can transform herself into a man, her genitals into a sledge with a dog to pull it "made out of a lump of snow she had used for wiping her end" (Q 6). Rasmussen's record of the foster-mother's shape-shifting introduces the shamanistic visions, metamorphoses and hybrid conditions prevalent throughout the collection, and which find their most complex expression in the closing long poem 'The More a Man Has the More a Man Wants.' This work takes the form of a series of forty-nine sonnets which improvise on the forty-nine sections of the Winnebago trickster cycle of stories as recorded by the anthropologist Paul Radin in his book The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology (1956). Radin's version, it should be pointed out, downplays trickster's acts as culture hero/transformer; in Muldoon's reworking of the tales, trickster's role as 'maker' is perhaps assumed more by the poet than his creation. Taking his cue from Radin's retelling of trickster's exploits, Muldoon relates the story of Gallogly, a republican terrorist on the run in Northern Ireland, whose bungling antics, gastrnomic and sexual appetites and shifting of shape from coyote to bear to hare, horse and mole identify him as a Sweenesque outsider (at one point he does transform into a manner of bird man) who transgresses rules and boundary lines. It is important to note that this central character's name, Gallogly, is itself a 'transformation' of the Irish galloglach, or gallowglass, meaning foreign soldier, or mercenary. Part of Gallogly's quest, though he himself does not recognise it, is the need to come to terms with the implications of that name -- his identity is not 'pure Irish'. 23 When the poem opens it is four a.m. and Gallogly is squatting, coyote-style, "in his own pelt." Six minutes previously a charter flight from Florida touched down at Aldergrove airport: Its excess baggage takes the form of Mangas Jones, Esquire, who is, it turns out, Apache. He carries only hand luggage. 'Anything to declare?' He opens the powder-blue attachecase. 'A pebble of quartz.' 'You're an Apache?' 'Mescalero.' (Q 40) Mangas Jones's geneology -- apparently he is Welsh, English, Mescalero Apache and, as we discover later, Oglala Sioux -- links him to Gallogly -- "otherwise known as Golightly,/otherwise known as Ingoldsby,/otherwise known as English" (Q 58) -- who also has mixed bloodlines. Mangas Jones's namesake, the Chiricahua Apache chief Mangas Coloradas, was a 'terrorist' involved in guerrilla-style raids and counter-raids along the Mexican border during the 1840s and 1850s, and thus creates another connection with the central character. While "har[ing]" his way towards the Armagh/Tyrone border, where he consumes "a brave dale" of damson plums and proceeds to shoot a U.D.R. corporal, Gallogly recalls "one evening after the night before" in the Las Vegas Lounge and Cabaret: when his eagle eye 24 saw something move on the horizon. If it wasn't an Indian. A Sioux. An ugly Sioux. He means, of course, an Oglala Sioux busily tracing the family tree of an Ulsterman who had some hand in the massacre at Wounded Knee. (Q 48) Like too many Hollywood directors, Gallogly assumes that any Indian is a Sioux Indian. Beyond a simple critique of racial stereotyping, however, what the narrator implies here is that, in broadly symbolic terms, Mangas Jones is in Northern Ireland to take revenge for, or at least as a reminder of, Ulster's contribution, in the form of five presidents and a hefty contingent of frontiersmen, to the suppression of Native America. More whimsically, though, Mangas Jones is also hunting the elusive Gallogly. As Muldoon has sumarised the plot: In the aisling or 'dream-vision' which forms the middle section of the poem, Gallogly muses on his own mercenary past. He has made an abortive trip to the United States to buy arms, in the course of which he imagines himself to have killed a girl. That, for him, is the root cause of his present plight, the reason for his being pursued by an avenging Indian.32 25 The identification of Gallogly with Mangas Jones is reinforced by the fact that Gallogly is an analysed rhyme on Oglala, and in light of Muldoon's gloss on the poem it is reasonable to read Mangas Jones as Gallogly's own troubled conscience. His concern than in "lob[bing]/an arrow into the undergrowth" (Q 56) he may have killed an American girl named Alice A. is linked to both an unacknowledged collective guilt about the "big-eyed, anorexic" girl tarred and feathered for her dalliance with a British soldier and to an anxiety that republican devotion to the aisling vision of Ireland -"Was she Aurora, or the goddess Flora,/Artemidora, or Venus bright" (Q 57) -- may not be worth the price. Gallogly's identity crisis, expressed through his shape-shifting and his strenuous efforts to be 'pure' Irish (despite the fact that he finds "that first 'sh'" in "Sheugh" "increasingly difficult to manage"), is epitomised in his relationship to Mangas Jones. For if Mangas Jones represents the still small voice of Gallogly's conscience, he also embodies his alter ego. In a world where Winnebago signifies a brand of family camper, Mangas is the exotic, romanticised 'real Indian' which, despite his racist attitudes, Gallogly fantasises himself to be. Thus when Mangas Jones touches down at 3.54 a.m., he becomes the dream-self that 'twins' or 'doubles' Gallogly until, exploded by a booby-trap bomb, he -- they -- utter Thoreau's "alreadyfamous last words/Moose . . .Indian" (Q 64). That this conflation of characters is part of the poem's design is indicated when, in a rewriting of one of the Winnebago trickster's antics, Gallogly "seizes his own wrist" and presses "an Asprin-white spot…into his own palm." Alluding to Treasure Island, the narrator explains that it was "As if Jim Hawkins led Blind Pew/to Billy Bones/and they were all one and the same" (Q 45). 26 A divided self, unwilling to acknowledge his 'mongrel' geneology and desiring to be someone he is not, the trickster Gallogly requires the healing powers of the shaman. What Muldoon's trickster tale seems to convey is that the 'cure' for Ulster's troubles lies in a recognition by both sides that Irish identities are not 'pure' but hybrid, that English and Irish, Euramerican and Native American, are not mirror opposites but "all one and the same". The pebble of quartz carried by Mangas Jones from Robert Frost's poem 'For Once, Then, Something', in which the speaker wonders whether the "whiteness" glimpsed at the bottom of a well is "Truth" or merely "A pebble of quartz,"33 may or may not contain that knowledge. That Gallogly is "none the wiser" in the instant before he is blown to smithereens suggests that for him it does not: the "hairy han'" found clinging to the "lunimous stone" is an image of hardened fanaticism. Gallogly's story may be one of pointless devotion to the cause, but in telling it Muldoon brings together Native and Euramerican cultures in a way that enacts the integration Gallogly resists. Psychic health, the poem implies, communal as well as individual, lies not in rigid division, but in 'the mixture.' That same imperative informs what to date has been Muldoon's most elaborate involvement with Native America. 'Madoc - A Mystery' is a 233-part narrative poem, the title of which alludes to a legendary twelfth-century Welsh prince who supposedly arrived in America before Columbus, he and his entourage assimilating with the Mandan nation. The myth was used to support Britain's prior claim to the New World, and was the basis for a poem, also called 'Madoc', by Robert Southey. Muldoon's 'remake' challenges Southey's assertion of the superiority of European over 'primitive' cultures, and revitalises the Madoc legend to fuel a critique of colonialist ideology. The narrative proper concerns itself with, among many other things, relations between a group of settlers and indigenous peoples in post-independence America. 27 The poem takes as its premise the notion that the two English Romantic poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey actually succeeded in carrying out their plan to found a utopian 'pantisocracy' on the banks of the Susquehanna River. This fantasy is transmitted, not by a speaking persona, but as a "retinograph" projected from the disintegrating eyeball of a man called South, a present-day descendant of one of the poem's eighteenth and nineteenth-century characters. The fragmented, atemporal way in which the story is conveyed, combined with a characteristic Muldoonesque play with words and their meanings, renders the poem's structure and style distinctly tricksterish; that 'Madoc - A Mystery' also constitutes a shamanic vision-quest for a curative form of knowledge indicates the increasing complexity of Muldoon's inscription of Native America. On a basic representational level, the presence of Natives within the text is notably inclusive and accurate. Muldoon's pantisocrats interact not with noble savages or bloodthirsty demons, but with Mandans, Cayugas, Spokanes, Mohawks and Senecas who are carefully defined 'flesh and blood' human beings, and whose behaviour, like that of the English settlers and Scots-Irish frontiersmen, ranges from the despicable to the honourable. The integration into the narrative of culturally specific myths and practices (such as the Seneca origin story of Sky Woman and her sons Flint and Sapling, or the Cayuga Society of False Faces), of the character and politics of actual Native leaders Red Jacket, Handsome Lake, Cornplanter and Joseph Brant, and of a virtual lexicon of Native words (moccasin, kinnikinnick, wannigan, quamash, toboggan) all contribute to a historically and ethnologically precise picture of Native realities in the 1800s. It is perhaps reasonable to assume that because the time frame of 'Madoc' (the seventy-five years between 1798 and 1873) begins with the five nations the Iroquois Confederacy dispossesed of their lands and ends with 28 Kentipoos (Captain Jack) and his followers defeated in the Modoc War of 1873, the poem, as Tim Kendall has put it, is "a paean (and elegy) for the culture of the native American tribes."34 But it is, I think, equally if not more important to realise the way in which the presence of Native America in 'Madoc', usually distorted or excluded altogether, writes these cultures back into contemporary Euramerican literary conscience. As in his earlier work, by giving Native America a voice and a presence, and by creating a 'hybridised dialogue' between cultures, Muldoon enriches our perspectives on both. Also in common with the earlier lyric poems, 'Madoc' indicts European and, particularly through the violent Scots-Irish scout Cinnamond, Irish/Northern Irish colonisation of Native America. Muldoon makes his critique in numerous direct and subtle ways, for example by contrasting the difference between Native and European concepts of land ownership. Whereas the Iroquois and other nations see themselves as the custodians, not the masters, of nature, the rich Irishman Blennerhassett is busy 'civilising' the land by building a Roman villa: That rather unsightly stand of birch and sugar-maple is destined soon to become a lawn.35 Muldoon also forcefully demonstrates, as Jacqueline McCurry has argued, that "such utopian schemes as Coleridge's and Southey's -- like the Enlightenment, 29 Romanticism, and Jeffersonian democracy -- were both elitist and racist."36 The differing responses of the two poets to the inhabitants of the New World is an index of Euramerica's failures and successes in coming to terms with Native America. Southey barricades himself into the settlement he dictatorially christens Southeyopolis, proscribing Native religious ceremonies and flogging his Native slaves, and is ultimately murdered by "the ghosts of a thousand Cayugas." Coleridge, on the other hand, abandons his search for his missing wife Sara to pursue his own vision-quest for the 'truth' about the Madoc legend. Guided by "Betimes a cormorant, betimes a white coyote" (M 224), he gradually assimilates into the Native world; his trickster-like shifts in name and his shamanistic illuminations link him not to his fellow-pantisocrat but to the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake, who also "sets out on an inner/journey along the path covered with grass." (M 212) At the moment of his death, Coleridge is completely nativised: Coleridge insinuates himself through this crack into the vaults of the Domdaniel. His familiar is a coyote made of snow. (M 241) As Tim Kendall has percepively noted, "His journey is both self-medicinal and, perhaps, a cure for colonialism."37 What Coleridge embraces, in his life and in his death, is what Southey (not unlike Gallogly) in his poetry and in his despotism stubbornly resists: the possibility of the hybrid moment, of meeting and mixing and 'dialoguing' with the 'other'. The 'mystery' in 'Madoc', then, is not so much the whereabouts of Sara as, if we understand 'mystery' in the Native sense of the word as 'medicine' or 'power', the healing and empowering knowledge that genuine humanity 30 lies not in fixed identities but in fluid ones. By confirming that the Welsh Madoc did not remain racially pure, but assimilated with the indigenous peoples he encountered in America, Coleridge's vision-quest encodes the substance of Muldoon's inscription of Native America: that the frontier is no longer a geographical but a transcultural one, a space where discourse is "richly hybridised" and "multidirectional." That, as the last section of the poem tells us, "It will all be over, de dum,/in next to no time -" (M 261) reminds just how fragile that discourse may be. Muldoon has remarked of the opera Shining Brow, "…some of the hokum that Wright talks about Indians is really commenting on some of the hokum I talk. Basically, it is saying, 'Hey, look. Stop doing this.'…maybe I've done it just once too much."38 For all its self-parodic elements -- Wright's obsessive invocation of Native names for alliterative effect, his tricksterish shape-shifting to elude reporters ("He melts into thin air./He takes a thousand forms" (SB 41)), Sullivan's dream of "a virile and indigenous architecture" -- Shining Brow extended and indeed sharpened Muldoon's incisive perspectives on Native America. His libretto reminded audiences of the damaging effects of stereotyping and endemic poverty on Native peoples, that America is a land "not 'borrowed' but 'purloined'" (sb 76), that the so-called 'primitive' Sioux, Shoshone, Hopi and Haida could certainly have taught the classical world "a lesson in harmony" (SB 106). And against Wright's resigned conclusion that the Native nations "have all gone into the built-up dark" (SB 86), it asserted, as Muldoon's previous works had done, the living voice and presence of Native Americans in the contemporary United States. To return to Louis Owens and the Native writers he speaks for and about, it is to be hoped that Paul Muldoon, like the hybrid mixedblood, with continue to be a "cultural breaker, break-dancing trickster-fashion through all 31 signs, fracturing the self-reflexive mirror of the dominant center, deconstructing rigid borders…and contradancing across every boundary."39 32 Endnotes 1 Paul Muldoon, Shining Brow (London: Faber, 1993): 85-6. Hereafter cited within the text as SB. See Jacqueline McCurry, "'S'Crap': Colonialism Indicted in the Poetry of Paul Muldoon," EireIreland 27.3 (1992): 92-107; Jacqueline McCurry, "A Land "Not 'Borrowed' but 'Purloined'": Paul Muldoon's Indians," New Hibernia Review 1.3 (Autumn 1997): 40-51; Tim Kendall, Paul Muldoon (Bridgend, Wales: Seren, 1996); Clair Wills, Reading Paul Muldoon (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, 1998). 3 Louis Owens, Other Destinies: Understanding the American Indian Novel (Norman: U of Oklahoma Press, 1992): 14. 4 Louis Owens, Mixedblood Messages: Literature, Film, Family, Place (Norman: U of Oklahoma Press, 1998): 26. 5 See for example the short story "Death of a Chieftain," in John Montague, Death of a Chieftain (1964; rpt. Dublin: Poolbeg Press, 1978): 139-168. 6 Paul Muldoon, New Weather (London: Faber, 1973): 39. Hereafter cited within the text as NW. 7 See Theodora Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds: A Biography of the Last Wild Indian in North America (Berekeley: U of California Press, 1961; rpt. 1989); Robert F. Heizer and Theodora Kroeber, Ishi the Last Yahi (Berkeley: U of California Press, 1979); Jed Riffe and Pamela Roberts, Ishi, the Last Yahi (Berkeley: Rattlesnake Productions, 1992), videocassette. 8 Paul Muldoon, "Notes for 'Chez Moy: A Critical Autobiography'," (unpublished MS., 1994), cited in Wills, Reading Paul Muldoon: 38. 9 Paul Muldoon, Quoof (London: Faber, 1983): 16. Hereafter cited within the text as Q. 10 McCurry, "S'Crap': Colonialism Indicted in the Poetry of Paul Muldoon": 98. 11 Paul Muldoon, Interview with Lynn Keller, Contemporary Literature 35.1 (1994): 19. 12 McCurry, "A Land "Not 'Borrowed' but 'Purloined'": Paul Muldoon's Indians": 46-7, 51. 13 Homi K. Bhabha, "Sly Civility," October 34 (1985): 78. 14 Homi K. Bhabha, "Signs Taken for Wonders: Questions of Ambivalence and Authority Under a Tree Outside Delhi, May 1817," in Europe and Its Others, vol. 1, ed. Francis Barker et al (Colchester: University of Essex, 1985): 104. 15 Paul Muldoon, Coming to Terms, BBC Radio 3, 12 March 2000. 16 Wills, Reading Paul Muldoon: 40. 17 Paul Muldoon, "The Goods," in Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing, eds. Peter Fallon and Sean Golden (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1980): 202. 18 Paul Muldoon, The Annals of Chile (London: Faber, 1994): 31. Hereafter cited within the text as AC. 19 Owens, Mixedblood Messages: 33. 20 Soft Day, 199. 21 Paul Muldoon, Why Brownlee Left (London: Faber, 1980): 24. Hereafter cited within the text as WBL. 22 Paul Muldoon, Meeting the British (London: Faber, 1987):15. Hereafter cited within the text as MB. 23 Sir Jeffrey Amherst and Colonel Henry Bouquet in Francis Parkman, The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada, vol. 2 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1922): 44-45. 24 McCurry, "S'Crap': Colonialism Indicted in the Poetry of Paul Muldoon": 95. 25 Kendall, Paul Muldoon: 145. 26 Paul Muldoon, Muldoon in America, Interview with Christopher Cook, B.B.C. Radio 3, 1994. 27 Wills, Reading Paul Muldoon: 118. 28 See, as above, McCurry, Kendall and Wills. 29 Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette Molin, The Encyclopedia of Native American Religions (New York: MJF Books, 1992): 260-61. 30 Larry Ellis, "Trickster: Shaman of the Liminal," Studies in American Indian Literatures 5.4 (Winter 1993): 55-56. 31 See Mac Linscott Ricketts, "The Shaman and the Trickster," Mythical Trickster Figures: Contours, Contexts and Criticisms, eds. William J. Hynes and William G. Doty (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993): 87-105. 32 Paul Muldoon, "Paul Muldoon writes…," The Poetry Book Society Bulletin 118 (Autumn 1983): 1. 33 Robert Frost, "For Once, Then, Something," The Poetry of Robert Frost, ed. Edward Connery Latham (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969): 225. 34 Kendall, Paul Muldoon: 157. 35 Paul Muldoon, Madoc: A Mystery (London: Faber, 1990): 88. Hereafter cited within the text as M. 2 33 36 McCurry, "A Land "Not 'Borrowed' but 'Purloined'": Paul Muldoon's Indians": 43. Kendall, Paul Muldoon: 169. 38 Muldoon, Interview with Lynn Keller: 19. 39 Owens, Mixedblood Messages: Literature, Film, Family, Place: 41. 37 34