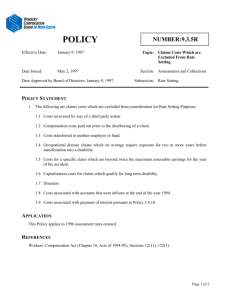

second injury funds

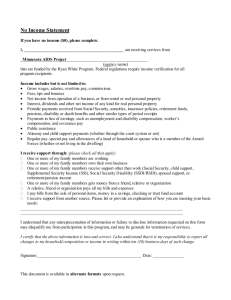

advertisement