The Changing world of the expatriate manager

advertisement

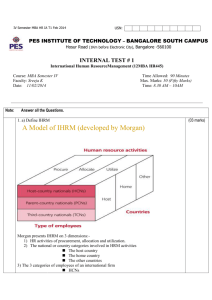

The Changing world of the expatriate manager By Dr Hilary Harris, Director of the Centre for Research into the Management of Expatriation (CReME) The word ‘expatriate’ conjures up images of colonial outposts, gin and tonics at the club and lavish benefits for pioneering men bringing enlightenment to far flung corners of empire. Whilst there may be some lucky expatriates still enjoying a luxury lifestyle, the world of expatriation is changing dramatically and permanently. To achieve competitive advantage in an increasingly global economy, organisations from both the private and public sector need to view the management of expatriates as a critical part of their international human resource management strategy. Employing an expatriate costs an estimated three to four times as much as employing the same individual at home. This has implications for who is picked for international assignments, why people are sent and how this fits into the organisation’s overall global strategy. Taking an expatriate assignment no longer automatically leads to a promotion on return. Individuals now need to network and be proactive in determining their own path forward. The advantages of huge financial packages are also slowly disappearing as organisations move towards equalising terms and conditions between expatriates and locals. In future, fewer and fewer people will be career ‘expats’. International experience Expatriates may be losing their security blanket, but the challenges and potential long-term rewards of taking an international assignment are growing. Most global organisations see international experience as a prerequisite for promotion to the top jobs. Although this experience can be gained from working in cross-border teams and projects, expatriation remains the preferred way of creating a global mindset amongst managers. However, there is a need for new skills and abilities amongst expatriates, and for far more careful planning and monitoring of assignments by organisational headquarters. This is the result of three main factors. The first is the changing nature of international organisations, with many more joint ventures and alliances across national boundaries. The Financial Times (28 July 1999) reported cross-border media, technology and internet deals reaching record levels in the first part of 1999. In just one example, the value of European acquisitions in the technology sector in the US increased 293% to $72.8 billion. Working effectively in an international joint venture or alliance requires high levels of interpersonal and cross-cultural skills on the part of expatriate managers. We are also witnessing the emergence of small to medium-sized organisations (SMEs) as key players in global trade. Appropriate deployment and management of expatriates can be critical in the initial stages of internationalisation, implying an urgent need for SMEs to develop effective systems in this area. The second factor is a change in host locations, with a decline in the proportion of expatriates going from the developed world to the Third World. At the same time, there has been an increase in assignments between developed countries as a result of extensive European, Japanese and US foreign direct investment and cross-border developments in New World trading blocs. Figures from the latest survey of expatriate management trends by Organization Resources Counselors Inc (ORC) shows the most popular regional destinations for expatriates are Asia (33%), Western Europe (26%) and the United States (16%). Expatriate managers working in countries with highly educated and professional employees can no longer adopt an autocratic approach. Motivation and development of local country nationals is an integral part of creating a truly global operation and as such should be reflected in performance measurement of expatriate managers. The third key factor concerns the changing nature of international assignees themselves. The traditional profile of the male, married, career expatriate is rapidly giving way to well-educated managers undertaking one or two assignments in the course of their career in order to gain international experience. Women still represent only a small proportion of international assignees, but this number is increasing. For these people, the costs and benefits of undertaking international assignments have to be very carefully assessed. Women in International Management: Still a long way to go. In a recent UK study carried out by Cranfield, only 9% of 3,620 expatriates surveyed were women and only 5% of those in management roles were female. The study questioned traditional organisational reasons for failing to send women on expatriate assignments. Fears about acceptance of women by local nationals were found to apply to only a small percentage of expatriate destinations. Even then, sensitive handling of cultural expectations often resulted in successful expatriation experiences for women in potentially hostile environments. The study also found that women were just as interested in taking up expatriate appointments as men. Dual-career issues were seen to be problematic, but not just for females. The main barrier to women taking up international assignments appeared to be the operation of closed, informal selection systems in which candidates were unaware that they were being considered and selection criteria were not formally agreed. In these cases selection decisions were highly dependent on the personal preferences and assumptions of selectors. Given the overwhelmingly male profile of expatriates, selecting a woman is often seen as too risky in a high cost, high profile position. The expatriate cycle For organisations to ensure effective expatriate management, a strategic approach should be taken to the whole expatriate cycle. Figure 1. The expatriate cycle The cycle starts at the planning stage. Traditionally, expatriates have been sent abroad for the following reasons: control and co-ordination of operations transfer of skills and knowledge managerial development In order to operate strategically, organisations need to link foreign assignments more closely to the strategic operational requirements. This requires a careful assessment of whether an expatriate is the best and most cost-effective choice in global sourcing decisions. Problems of lack of strategic planning One international company decided to reduce its costs by cutting the number of expensive expatriates it employed around the world by one quarter. The decision was taken at main Board level but had to be implemented by the international HRM manager. ‘No business manager was prepared to tell me that he was running an unsuccessful operation,’ he said ‘so the only thing we could do was to “localise” some of the jobs.’ Within two years he had achieved the objective: at around the same time, the company realised that whilst some of the local replacements had been obviously successful, some of the changes had been – equally obviously – disastrous. Over the next few years the company began to increase the number of expatriates again. ‘Of course,’ the IHRM manager said ‘we shouldn’t have started with a decision on numbers; we should have found some way of working out which jobs needed to be filled by expatriates and which didn’t. We’ve tended to do it mainly by intuition.’ Cranfield has developed the ‘Expatriate Portfolio’ to help corporate managers identify how an international assignment should be managed and whether a local should fill it or an expatriate. The framework outlines four types of assignment based upon the degree of importance of the assignment to the parent organisation, and indicates the most suitable type of appointment for each instance. By plotting the assignment against the Portfolio, managers can make more rational and sensible sourcing decisions. Fig. 2 The Expatriate Portfolio Once a strategic decision has been made to use an expatriate in an international posting, the selection process starts. Research into criteria of effective international managers consistently highlights the importance of ‘soft’ skills such as selfawareness, flexibility, intercultural empathy, interpersonal skills and emotional stability. However, surveys of international selection practice within organisations show that most rely on technical competence as a prime determinant of eligibility for international assignments. ORC’s 1997 survey of International Assignment Practice also shows that only 8% of international organisations use any form of psychological testing during the selection process. Pre-departure training forms the next part of the cycle. Effective preparation can do much to alleviate culture shock and help the expatriate and his or her family to adjust more quickly to the new environment. In order to maximise the value of this for the expatriate and spouse/family members a framework has been developed by CReME which allows international HR managers to customise training to the unique needs of the expatriate and the assignment. Fig 3: Framework for Expatriate Preparation Using the checklist provided by the framework, managers could assess both the nature and extent of pre-departure preparation required for each individual. For instance, in the case of a manager from a large multinational organisation going to a set-up operation in Vietnam, the preparation would need to concentrate on cross-cultural, language and local business briefing, with substantial involvement from headquarters’ expatriate administration department in arranging accommodation and practical local living details. Monitoring performance whilst on an expatriate assignment requires an understanding of the variables that influence an expatriate’s success or failure in a foreign assignment. Three critical variables are the environment (for instance culture), job requirements and the personality characteristics of the individual. Organisations need to balance the desire for a global standardised performance appraisal system with the local requirements of subsidiaries. The final stage of the expatriate cycle is repatriation. For most organisations and individuals, this remains highly problematic. In ORC’s survey 57% of organisations reported that the job level to which expatriates are repatriated normally depends on what jobs are available at the time. Expatriates are now expected to be far more proactive during their time abroad and to network in order to ensure a position is available on return. For many expatriates, the impact of ‘re-entry’ can be more traumatic than the initial culture shock at the start of the assignment. Organisations need to pay careful attention to the way in which they handle repatriation for two key reasons. Firstly, the cost of losing someone who is dissatisfied with his or her position on return is significant, both in purely financial terms and also in terms of the investment in human capital. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, expatriate assignments are crucial tools in the effort to create a transnational mindset in the organisation. Failure to disseminate the individual learning gained from a foreign assignment to others in the organisation is a clear barrier to the goal of becoming a truly global operation. Successful management of expatriation requires an holistic approach to the whole expatriate cycle. Organisations that continue to send people on expatriate assignments without carefully considering how this fits into the strategic plan are likely to lose a valuable source of competitive advantage. They will also find themselves subsidising some very expensive gin and tonics! CReME is a collaboration between Cranfield School of Management and Organizational Resources Counselors, Inc. Launched in July 1999 it is the first of its kind dedicated to the development of new approaches in international human resource management and expatriate management.