INTI International University College

advertisement

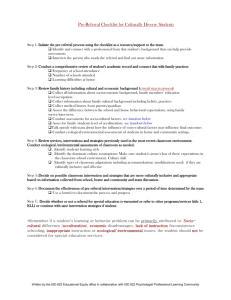

Acculturation Strategy among Malaysian students in Japan Ina Suryani bt Ab Rahim Communication Skills & Entrepreneurship Centre, University Malaysia Perlis. ina5131@yahoo.com Prof.Dr.Kuldip Kaur Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences, Malaysia Open University. Intan Maslina Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Oita University of Japan Scholar’s mobility and crossing borders in the pursuit of knowledge are becoming more common in the globalizing world. The bottom line for the international students is to do well academically and the perseverance in performing well academically is moderated by many factors. Failure to adapt to the changes in the new environment would tax on the psychological wellbeing, exhaust the students and strain the academic performance. Acculturation which is a part of the moderating factor for adaptation can be assessed by measuring the assimilation into the host culture and retention of the origin culture. Researchers have pointed out that most western theories and findings on adaptation for international sojourners could not capture the phenomenon happening in Japan due to the unique nature of the Japanese host and sojourners. Researches on international students in Japan fall short at clarifying the experience of the Malaysian students in the country. This paper focuses on the need for a measurement tool such as acculturation scale for Malaysian students specifically in Japan by looking into the acculturation studies that has been conducted in both Japan and the West. This paper also discuss the relevant constructs from other acculturation scales such as the Indonesian Acculturative Rating Scale (IARS) proposed by Hondojo (2000) and Acculturative Scale for Asians (ASA) by Kim (2001). The implication of the study is a possible extension on the theory of acculturation strategy which is widely used in the western research, by adding an alternative culture option to the list of preferred culture. It is hope that this study would support effective counseling by suggesting evidence in avoiding generalization and stereotyping of western cases in the counseling, orientation and intervention programs for Malaysian students in Japan universities. Introduction The bottom line for most students is to do well academically and the perseverance in performing well academically is moderated by many factors. These moderating factors are more complex in the case of the students abroad as they need to face inevitable changes in life. As Handojo (2000) summon up from Berry and Kim (1988)”The many dimension of changes need to be faced are namely: physical (new weather and climatic conditions), biological (different foods, diets and diseases), social (cutting off from previous friendship and making new friends), cultural (being uprooted from indigenous political, social and religious context), and psychological (the need to change attitudes and values).” For the international students, the adaptation extends to other changes in dimensions of academic, language, financial and homesickness. Failure to adapt to these changes would collapse the students’ daily performance and functioning and could lead to negative outcomes in the students’ health, psychological wellbeing and academic performance in the long run (Poyrazli et al., 2001). Being uprooted from the common ground, support, intervention and counselling by counsellors or support group are crucial especially when studies (Maruyama, 1998; Takebayashi, 2004), Kim 2001) have shown the acute effects on psychological health when acculturation problem is failed to be address The person with high acculturative stress is susceptible to various psychiatric symptoms (Takebayashi, 2004). Imperatively the students must be capable to dole out the stress and recognize activities that help them make progress in adaptation. Western scenario Counsellors are kept informed about the recent development in adaptation by intercultural adaptation studies which are particularly advance in the western context. Lysgaard’s (1955) U curve hypothesis for adaptation has been the tenets of many western studies (Handojo, 2000; Ninggal, 1998; Takebayashi, 2004; Michailidis, 1996) have suggested that adjustment difficulties changes upon length of stay. Initially, the novelty of being abroad raises the level of satisfaction and adjustment among the international students but after sometimes, they are brought down by homesickness and other adjustment problems and as they are more involved, they further worry about maintaining the academic standards (Jamaluddin, 1987). Confirming Lysgaard (1955), Jamaluddin (1987) further suggested that as time goes by, familiarity with the culture, greater mastery of language and social skills, higher level of adjustment is acquired. Ninggal (1998) also suggested that “Faced with recently arrived and unhappy students, counsellors could help make clear to the students that nearly all international students confront feelings of unhappiness and frustration that will probably pass with time.” In short, an optimistic view in the relation to adjustment and length of stay is a common belief when dealing with international students. Apart from time factor, studies conducted on western scenario also found that host language proficiency is one of the important factors in adaptation mainly on educational stress (Gholamrezaei, 1996; Ninggal, 1998; Sheehan & Pearson, 1995; Abu, 1995). Greater mastery of the host language in the Western case, English language would assist in understanding lectures and academic discussions, carrying out day to day task and other social activities. Cultural distance is another factor influencing the rate of acculturation. For example, most American students would rather strike up conversation with someone who looks similar to them culturally and ethnically (Ninggal, 1998). This is especially true when the European students naturally adapt faster to the American college life compared to the Japanese or Arabs students. Japan Scenario Researchers have pointed out that most western theories and findings on adaptation for international sojourners could not capture the phenomenon happening in Japan due to the unique nature of the Japanese host and sojourners. The studies in Japan (Tsai,1995; Maruyama,2004; Tanaka,1994) suggest a different pattern from the Lysgaard (1955) model which has been the axis to many western studies (Handojo, 2000; Ninggal,1998 ; Takebayashi,2004; Michailidis,1996). Moyers (as cited in Maruyama 2004) suggested that time does not play a factor in assisting adaptation among international students in Japan. Tanaka (1994) found that majority of the international students in Japan shows a differing experience from Lysgaard (1955) U curve. Tsai (1995) reported that length of stay for Asian students did not have significant and positive changes in their attitudes toward the host. His study further uncover that students in Japan tend to have cultural shock in their third year of stay and do not significantly recover from this stage afterwards. It was also found that the international students who stay longer in Japan show more dissatisfaction instead of more understanding on the host culture (Maruyama, 1998). International students in Japan unlike their friends in the western counterparts do not improve their psychological adaptation over the length of residence especially for Asian (Maruyama, 1998; Tsai, 1995) On top of finding that the length of stay in Japan does not necessarily correlate with adaptation and they also found that the whites conformed to the U shape Lysgaard (1955) U shape model but the Asian don’t (Hagiwara, 1991; Iwao& Hagiwara, 1987 as cited in Maruyama, 1998). Iwao & Hagiwara (1991; as cited from Maruyama, 1998) found that cultural similarities do not assure higher acculturation. Tanaka (1994) added that Asian students were less adjusted then other international students despite sharing some similarities in culture. Increase score were reported on the perception on the Japanese host as being honest, diligent but unfriendly and cold. They also found mastery of the Japanese host language does not guarantee psychological wellbeing (Moyer, 1989; Okazaki, 1992; Araki, 1989; Tanaka &Fujihara, 1992; as cited in Maruyama, 2004). As summon up by Maruyama, contradictory to the western studies, the communication problem doesn’t seem to decrease with better language acquisition as the root of the problem lies deeper than words. Some of the problems pointed out are ambiguity of expression by Japanese people, attitude of Japanese people towards foreigners, indirect expression and suppressed expression. Those who make attempts to learn about Japanese language, people and custom experience more stress due to rejection by the host then did less motivated students (Tsai,1995).The differences in the western and Japanese research findings bring on inconclusive understanding on the relation of acculturation and psychological wellbeing. The differences in western and Japan research findings support that acculturation needs a specific study on each host and nationality of the sojourners. Generalization and stereotyping of western cases in the counselling, orientation and intervention programs for Malaysian students in Japan could lead to acute effects on the students’ psychological health as the actual acculturation problem is failed to be addressed. Since a single study can not explore all the problems associated with cross-cultural adaptation, this paper focuses on the initiating a discussion on constructing of an acculturation scale for Malaysian students in Japan. Acculturation. Acculturation is defined as a process of cultural change that results from repeated, direct contact between two distinct cultural groups (Hall et.al., 2003). Studies have been carried out from the host perspectives and the scholars’ perspectives (Maruyama, 1998; Gholamrezaei, 1997; McClelland, 1996). Focusing on the scholars’ perspective, Berry (1980) has proposed 4 modes of acculturation based on the attitudes towards the culture of origin and host. He suggested that acculturation can be assessed by measuring the degree of assimilation to the host culture and degree of retention of the origin culture. The four modes suggested are Assimilation, Integration, Separation and Marginalization. He described Assimilation mode as acceptance of the host culture and losing of one’s original culture identity. Integration mode is considered as the most preferable as it promotes the balance between retaining one’s origin culture and accommodating the new culture apart from promoting biculturalism (Takebayashi, 2004; Sowodsky, 1991; Hondojo, 2001). In Separation mode, cultural heritage is retained while the new culture belonging to the host is rejected and in Marginalization, the individual does not identify with either culture of the origin or the new culture belonging to the host (Berry, 1997). He further added that the person is suspended between the cultures and becomes isolated with tendency for personal and social conflict. This mode has demonstrated the highest level of stress, confusion, anxiety and depression (Takebayashi, 2004). Studies on adaptation have always been linked to psychological, cultural learning, social identification, economic trends and other fields. Ward (2001) proposed a framework for acculturation that linked three branches of major theories. The theories linked are Stress and Coping theories, Cultural and Learning theories and Social Identification Theories. In order to conduct a comprehensive but focused study, it is absolutely necessary to establish a reliable and valid measurement tool. The existence of a valid and reliable acculturation scale would be a useful tool for connecting adaptation with psychological, cultural learning, social identification, economic trends and other fields which are gaining importance due to globalization. Lessons from existing acculturation scales The existence of tested acculturation scales by previous researchers especially the scales concerning Asians provides a starting ground for tailoring an acculturation scale for Malaysian students in Japan. Unlike some psychological scales, it is not possible to use any of the scale as a whole due to the multifaceted nature of acculturation explained earlier. Other then the unique nature of acculturation, no specific study has been conducted specifically on Malaysian students in Japan has been identified. Most of the researchers define Asian as Chinese, Koreans and Taiwanese (Maruyama, 1998; Tanaka, 1994; Takebayashi, 2004). These nationals share the same writing system with the Japanese in “Kanji”. It is important not to generalize the findings to the Malaysian ethnics who have more dissimilarity with the Japanese host compared to the Asian defined in previous studies. A study on Chinese Indonesian immigrants to the United States (U.S) focusing on association between adult attachment style, acculturation attitude and behaviours and levels of stress have used Indonesian Acculturation Rating Scales (IARS) as one of the measurement tool (Handojo, 2000). As the researcher puts it, the IARS is actually a modification of The Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican American ARSMA-II developed by Cuellar, Arnold and Maldonado (1995). Handojo has changed some of the wordings in the items to suit the Indonesian immigrants. IARS measures the four modes of acculturation by Berry (1980). The items for IARS are based on four factors ;(a) language use and preference, (b) ethnic identity and classification, (c) cultural heritage and ethnic behaviours, and (d) ethnic interaction. IARS consist of two independent scales. The first scale measured the integration and assimilation, whereas the second scale measured separation and marginalization modes. Acculturation Scale for Asians (ASA) was developed based on the Berry’s acculturation model (Kim, 2001) Kim (2001) intended ASA to measure the construct of acculturation for Asian populations in general. The scale consisted of 21 items that primarily focus on one’s preferences and attitudes toward Asian and American cultures. She developed the scale in several steps. Initially, other acculturation scales were reviewed for key item content. And then, five individuals were interview to generate more content items. Lastly, the students were interviewed again to review the combined list. Her study focused on the relation of acculturation, social support, alienation, and psychological distress among Asian American college students. In this case, using the ASA or the IARS in the context of the Malaysian students in Japan is not possible due to many differences. The differences begins with the Japanese host being monoculture and the American being more culture tolerant thus involves different cultural learning factors that could distort the whole findings. Another major difference has been identified in an interview session with the students which suggested the possibility of a third culture on top of the two cultures proposed in most acculturation scales. The third culture which is an alternative culture refers to the preferred culture adopted by the students and this culture is other then the host’ or the origin culture. It is hypothesised that the western culture which is also having a great impact on the Japanese youth could be a possible alternative culture. Alternative culture is like preference for English language usage in communication and academic purpose, western food and other international students as friends. The Alternative culture is most like to exist in Japan due to the homogeneity of the host culture and the smaller number of the Malaysian community in the area compared to other academic centres in the UK or US or Australia could also reduce the strength to adhere to the culture of origin. Conclusion Orientation and intervention programs are suitable means for dispensing information on promoting healthy acculturation. Counselling is also one of the sources for assistance and support that should be made available for international students especially those with acculturation problems. Generalization and stereotyping in dealing with acculturation problems would reduce the accomplishment of the programs and the counselling (Slodzinski 1994). Cuellar, Haris &Jasso (1980) has shown that the effectiveness of counselling can be affected by the client’s level or degree of acculturation into the dominant society. They further suggested that the programs and counselling should be address with consideration to different cultural sensitivity and needs. The study of acculturation is absolutely necessary in upholding the relevance of counselling for the case of Malaysian students in Japan. The availably of reliable and valid measurement tools would open more doors for further research in the area. It is hope that this paper would help in avoiding generalization and stereotyping of western cases in the counselling, orientation and intervention programs for Malaysian students in Japan. References Abu Al Rub,R.F.A (1995) A Focus Group Study among Asian International Students: Perceive Stressors and Coping Strategies. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas Tech. University Berry J.W (1980) Acculturation as Varieties of Adaptation. In A.Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, Models and Some New Findings (pp.9-25) Boulder, CO:Westview. Cuellar,I., Harris,L.C, & Jasso,R (1980) “An Acculturation Scale for Mexican American Normal and Clinical Populations.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science, 2,199-217 Gholamrezaei, A. (1996) Acculturation and Self- Esteem as Predictors of Acculturative Stress among International Students at the University of Wollongong Doctoral Dissertation University of Wollongong, Australia Hall,Gordon.C, Nagayama.(2002) Multicultural Psychology 2nd.ed,Prentice Hall N.Jersey Handojo, V (2000) Attachment Styles, Acculturative Attitudes/Behaviours and Stress among Chinese Indonesian Immigrants in the United States of America. Doctoral dissertation. Fuller Theological Seminary. Kim .A.(2001) The Relation of Acculturation, Social Support, Alienation and Psychological Distress among Asian American College Students, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Illinios Lysgaard,S. (1955) “Adjustment in Foreign Society: Norwegian Fulbright Grantees Visiting the United States.” International Social Bulletin, 7,45-51 Maruyama, M. (1998) Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Host Environment: A Study of International Students in Japan. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Oklahoma. McClellandA.N (1996) The Acculturation Attitudes and Acculturative Stress of International Students. Masters Dissertation Carleton University Canada Michailidis M.P. (1996) A Study of Factors that Contributes to Stress with International Students. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts Lowell. Ninggal (1998) The Role of Ethnicity among International Students in Adjustment to Acculturative Stress. Doctoral Dissertation, Western Michigan Univ. Poyrazli. S, Kavanaugh P.K and Baker.A (2001) “Adjustment Issues of Turkish College Students Studying in the United States” College Student Journal, 7(1), 73-83. Sheehan,O.T.O & Pearson,F (1995) “Asian International and American students’ Psychological Development.” Journal of College Student Development, 36, 522-529 Slodzinski, M.T(1994) An Acculturation Scale for Asians in the United States. Doctoral Dissertation, Indiana University US. Sowodsky, G.R., Wai,M.L.E, Plake, B.S (1991) “Moderating Effects of Sociocultural Variables on Acculturation Attitudes of Hispanics and Asian Americans.” Journal of Counselling and Development:JDC, 70 194-204 Takebayashi, Y (2004) Effects of Acculturation Strategies in the Sense of Entitlement and Psychological Wellbeing among Asian American. Doctoral Dissertation, Adelphi University Tsai H.Y (1995) “Sojourners Adjustment: The case of foreigners in Japan.” Journal of Crosscultural Psychology, 26(5), 535-536 Ward, C &Boshner S (2001) “The A,B,Cs of Acculturation: Theory Research and Applications” International Congress of Applied Psychology N.Zealand,