Nuclear Revision

advertisement

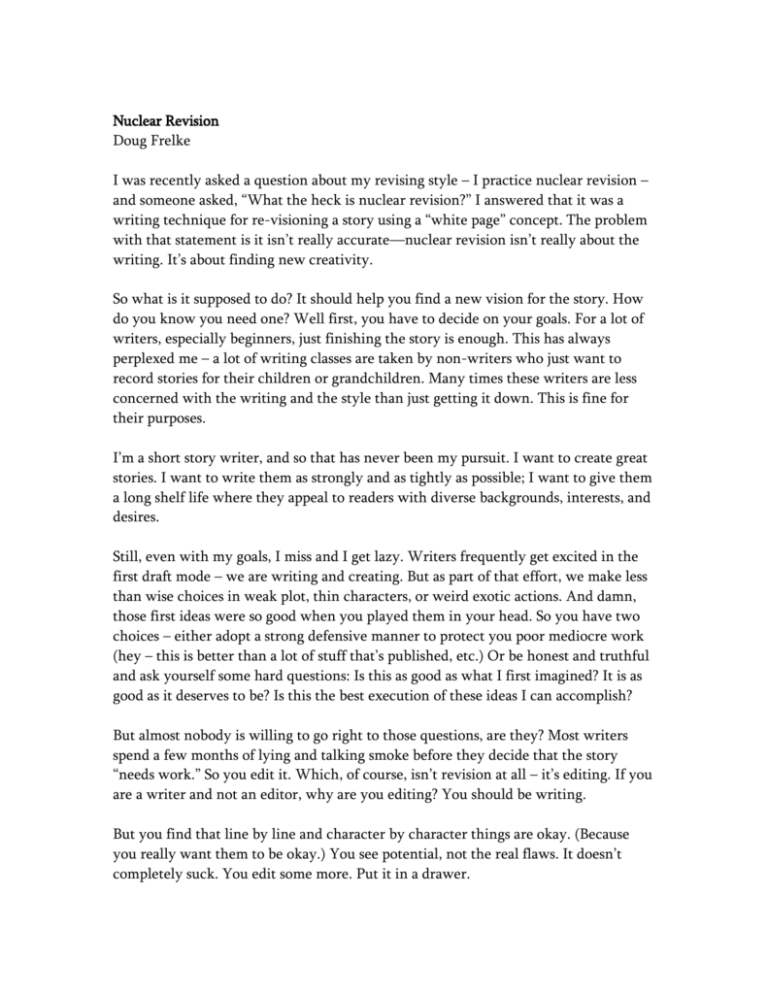

Nuclear Revision Doug Frelke I was recently asked a question about my revising style – I practice nuclear revision – and someone asked, “What the heck is nuclear revision?” I answered that it was a writing technique for re-visioning a story using a “white page” concept. The problem with that statement is it isn’t really accurate—nuclear revision isn’t really about the writing. It’s about finding new creativity. So what is it supposed to do? It should help you find a new vision for the story. How do you know you need one? Well first, you have to decide on your goals. For a lot of writers, especially beginners, just finishing the story is enough. This has always perplexed me – a lot of writing classes are taken by non-writers who just want to record stories for their children or grandchildren. Many times these writers are less concerned with the writing and the style than just getting it down. This is fine for their purposes. I’m a short story writer, and so that has never been my pursuit. I want to create great stories. I want to write them as strongly and as tightly as possible; I want to give them a long shelf life where they appeal to readers with diverse backgrounds, interests, and desires. Still, even with my goals, I miss and I get lazy. Writers frequently get excited in the first draft mode – we are writing and creating. But as part of that effort, we make less than wise choices in weak plot, thin characters, or weird exotic actions. And damn, those first ideas were so good when you played them in your head. So you have two choices – either adopt a strong defensive manner to protect you poor mediocre work (hey – this is better than a lot of stuff that’s published, etc.) Or be honest and truthful and ask yourself some hard questions: Is this as good as what I first imagined? It is as good as it deserves to be? Is this the best execution of these ideas I can accomplish? But almost nobody is willing to go right to those questions, are they? Most writers spend a few months of lying and talking smoke before they decide that the story “needs work.” So you edit it. Which, of course, isn’t revision at all – it’s editing. If you are a writer and not an editor, why are you editing? You should be writing. But you find that line by line and character by character things are okay. (Because you really want them to be okay.) You see potential, not the real flaws. It doesn’t completely suck. You edit some more. Put it in a drawer. Maybe, you decide to write something else. But look — how many great stories do you think you will write in your life? How many great stories did Carver write? Mauseupant? Poe? Hemingway? Not that many – maybe a dozen great ones for our strongest writers. And isn’t that what we should be trying to create? The great story that will be read 100 years from now? And maybe that piece of rough stuff is the one great story idea you’ve been given. Maybe. If you’d quit editing it, and act like a writer. So you decide to nuke it. You get the white pages out, and you start over. But see – nuclear revision requires a new vision. You have to start the revolution in your head – then the paper will follow. It’s not a problem of writing – even the crassest writer can move his fingers across a keyboard. But can he create? Nuclear revision is a gut check, brothers and sisters. How many fresh ideas do you have? How many good ideas are you willing to sacrifice for one great one? We are afraid of writer’s block. We are afraid of dumb ideas. We are afraid of wasting pages and pages and producing baby poo. Well, no one promised you a rose garden. I’ll give you an example: For my story “Imagining Dolores,” I started with an idea of a man that talked his way out of a ticket. (I’ve always wanted to be able to do that.) He lies and tells the cop he thought he saw his wife in someone else’s driveway. Only his wife is recently deceased. Cop lets him go. He tells the story at work; people misunderstand him – they think his wife has died. But he’s never been married. It was a just a lie to get out of a ticket. He meets a sympathetic soul, but his lies tie him up, and it ends badly for him. It was an okay story. But I nuked it. For the second try, I figured I needed a narrator that was observing the story. (I was wrong about that, but it was a fresh idea.) So I set the story with an HR Director who has to deal with a Slavic computer programmer named Pavlov. Pavlov has a whole created family – pictures, screen savers, and the rest. It only exists in his files though. Same kind of stuff happens. Pavlov chooses the computer life. The narrator tries to fix his own life and understand. Blah. I nuked it again. This time I used a Nigerian photographer. And he had a family that he imagined – only it was his own. A family that had existed before a tragedy. He lives his current life with a bunch of almost surreal practices – picture taking, ballroom dancing, life in these United States. And still he can’t forget the images that haunt him. I don’t know if it’s great, but it’s a keeper. A whole different kind of story than the ones before it. But this is key – one I couldn’t have accomplished without writing the first two. So there’s two ways to look at my process. First, you can say that I’ve invested a lot of time by producing three full stories (at about 15 pages each) to produce just the one keeper. Plus, I don’t seem to be showing my drafts any love. I mean I just walked away from two of them. Maybe I could have made them better. I could have. But maybe they don’t deserve love, huh? Maybe they are just drafts. Not of stories, but of my ideas. The second way to look at nuclear revision is the way I came to doing it in the first place – with the realization that workshops don’t work. I see writers in workshops all the time – and what do they do? They defend their drafts. They think of explanations. They edit and rewrite passages, maybe even whole scenes. And all of that eats up time and effort, and in the end, produces nothing of worth. On all levels, it is easier to talk about writing than to actually do it. Hell, just about anything is easier than writing. So why do I practice nuclear revision? Well, I am a serious writer, and I want to write great stories. Nuclear revision is filled with risks and fears – it reminds me of handling broken glass or raw poison – each time I commit to it, I get nervous. But I think that is one of its real advantages. Too many writers develop a publishable style and coast. They keep writing the same old way and creating similar characters. They use a gifted, but limited, set of tools to build their stories based on what has worked for them in the past. It’s where old writers go to die, and why writers like Peter Taylor and Robert Penn Warren were really good, but not great. Nuclear revision keeps me on my toes – it keeps me working hard. That’s what the writing really deserves. And it needs a continual stream of creativity to be really effective. Langston Hughes said that a writer should be able to think anything and write anything. But you can’t write what you haven’t spent time thinking about – hard. Plus, our minds have to be forced out of those easy thought channels and those overused ideas. Even then, your first stumbles at communicating those new thoughts and images are probably going to stink. You are going to need finer, sharper ideas – a creative mind that is well oiled and well honed. Nuclear revision makes you pull out the sharpener, makes you refine your concepts, your ideas, your images, your characters, even your plot. But you know the best thing about nuclear revision? When I finish a story using this process, I know it is done. It is the best I can do – at my current level of experience and ability. And I sleep like a baby.