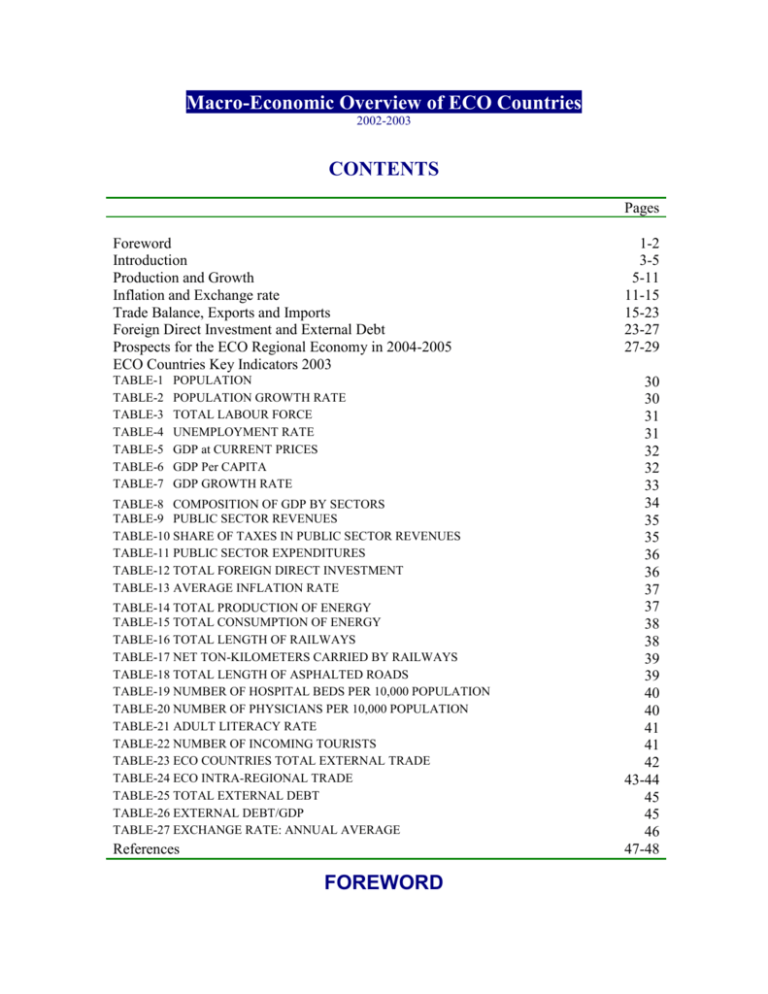

FOREWORD

advertisement