APUSH.PEPS(People.Events.Places.Significance)

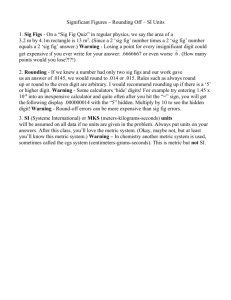

advertisement