![CCP-Toolkit-Feb[1]_0.](//s3.studylib.net/store/data/008556921_1-6ca692d82731004f5dfcfb8687640a32-768x994.png)

Condom

Programming

Toolkit

Draft – March 2009

Srdjan Stakic, EdD

UNFPA

2

INTRODUCTION TO THE TOOLKIT

5

PURPOSE OF THE MANUAL

AUDIENCE

FORMAT/CONTENT

WORKSHOP SIZE

WORKSHOP SCHEDULE

TEACHING AIDS

EVALUATION

NOTE ON THE PRINCIPLES OF ADULT LEARNING

AUTHORS

5

5

5

6

6

6

6

6

7

CHAPTER I: COMPREHENSIVE CONDOM PROGRAMMING

8

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

8

8

11

CHAPTER II: MALE AND FEMALE ANATOMY

18

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

18

18

19

CHAPTER III: REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

29

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

29

29

32

CHAPTER IV: BASICS ABOUT SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS AND HIV

41

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

41

41

42

CHAPTER V: DUAL PROTECTION

53

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

53

53

54

CHAPTER VI: INTRODUCING THE MALE CONDOM

58

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

58

58

59

CHAPTER VII: INTRODUCING THE FEMALE CONDOM

68

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

68

68

70

3

CHAPTER VIII: REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH COMMODITY SECURITY

74

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

74

74

75

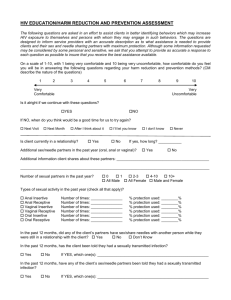

CHAPTER IX: RISK ASSESSMENT AND BEHAVIOUR CHANGE

81

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

81

81

82

CHAPTER X: ADDRESSING MYTHS, MISPERCEPTIONS AND FEARS AROUND CONDOMS

AND CONDOM USE

89

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

89

89

90

CHAPTER XI: CONDOM NEGOTIATION TECHNIQUES

104

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

PRESENTATION SLIDES

104

104

104

109

CHAPTER XII: OTHER HIV PREVENTION STRATEGIES AND INTERVENTIONS

110

OBJECTIVES

KEY POINTS

OVERVIEW

110

110

110

4

Introduction to the Toolkit

Purpose of the Manual

The purpose of this manual is to provide guidance to trainers

1. Who will serve as trainers of service providers in order to establish a large

cadre of professionals able to understand basic and advanced concepts of

male and female condom programming

2. Who will train, educate and counsel condom users or potential condom users

on how to users male and female condoms correctly and consistently

Audience

The primary audience of these tools are trainers in all regions of the world,

including physicians, nurses, NGO members, Ministry of Health representatives and

other relevant stakeholders. The assumption of the authors of this manual is that

audience members will have some previous understanding of medical and/or public

health concepts of HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health promotion

and thus only basic information will be provided in this toolkit.

Format/Content

This training manual is apart of the Generic Training Package (GTP) –

applicable in all cultural, religious and geographic areas/regions. The

process of adapting of this GTP will be conducted independently after the

completion of these documents.

This training manual utilizes adult-learning techniques and seeks to draw

from the experiences of service providers to develop solutions to any

problems they encounter in promoting male and female condoms. It takes

into account the cultural reality of different regions and offers service

providers skills I think the manual would not be able to provide skills but:

provide information on… promoting condoms.

All the topics identified in this GTP comprise the full training package on

male and female condom promotion. The training package fulfils the

following dissemination objectives:

a. Each topic/section may stand on its own for training purposes with

references or links provided for any related material that may be

within other sections.

5

b. Each section includes adequate age- and gender-balance in the

content of the material discussed reflecting the needs of both young

and mature men and women. This allows for greater adaptability of

the tools and wider use by service providers who work with various

populations.

Workshop Size

The recommended number of participants is 20 to 25 per workshop so that the

training may facilitate participation..

Workshop Schedule

The manual can be covered in full in five days or if necessary, trainers and

participants can adapt it as per the need of their program.

Teaching Aids

The manual includes all necessary teaching aids (case studies, exercises,

presentations, multimedia tools, etc.).

Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the workshop, trainers should ask participants to

take the same test before and after sessions. Questions to be given to participants

are included at the end of each session.

Note on the Principles of Adult Learning

Trainers who use this manual should follow the principles of adult learning. These

include1:

Adults learn best when they are actively involved in their own training and

when training builds on their own experiences and knowledge. As

participants in these workshops will be service providers, the assumption of

authors of this text is that they will carry with them a certain level of

knowledge and professional (and life) experience. Trainers should utilize

these in their work.

Adapted from: Reproductive Health Manual for Trainers of Community Health Workers.

(2003). Centre for Development and Population Activities and USAID. Available online at:

http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/1419

1

6

How you teach is as important as what you teach. The tools provided in this

manual should help you design your trainings in an informative and

interesting, attention-grabbing manner.

While lectures are sometimes necessary, research shows that they are not

the best way to teach. Adults learn best when training allows them to

discover their own solutions to problem. Thus, utilize discussion in large or

small groups and in pairs, exercises and other pedagogical methods that will

encourage participants to think and come up with their own answers to

various questions.

Adults learn best through doing. The next best way they learn is through both

seeing and hearing. As participants in these workshops will serve as trainers

themselves of the same subject, consider involving them in facilitating some

of the sessions.

Adults want to learn what they can apply immediately.

Given below are suggested methods:

o Use simple, appropriate, culturally, and religiously acceptable

terminology.

o Use games, discussion, case studies, demonstration, simulated

practice, question-and-answer sessions, brainstorming, etc.

o Move at a pace comfortable for the participants.

o Provide (positive) feedback to ensure a participatory teaching and

learning process.

Authors

Insert a note on the Interagency Group and the consultant.

7

Chapter I: Comprehensive Condom Programming

Objectives

To define the Comprehensive Condom Programming (CCP) approach

To understand what role service providers play in CCP

Key Points

Comprehensive Condom Programming

Comprehensive condom programming is an approach used to create and

strengthen:

Leadership and coordination

Supply and commodities security

Access, demand and utilization

Support

It integrates various activities including male and female condom promotion,

communication for behaviour change, market research, segmentation of messages,

optimized use of entry points (in both reproductive health clinics and HIV

prevention venues), advocacy and coordinated management of supplies.2

The goal of CCP is to reduce the number of unprotected sex acts, leading to fewer

unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections including HIV.

In other words, CCP seeks to develop strategies and programmes wherein every

sexually active person -- regardless of age, marital status, gender, sexual

orientation, economic situation, HIV status – has access to good quality condoms

when and where s/he needs them, is motivated to use males or female condoms as

appropriate and has the information and knowledge to use them consistently and

correctly.

CCP approaches may vary from country to country, depending on many factors.

Understanding your local epidemiology, distribution infrastructure, cultural context

and budgetary issues will be important for effective training.

CCP recognizes that both male and female condoms are essential for the prevention

of unintended pregnancy and STIs including HIV, known as dual protection. It

ensures that condoms are provided at many places -- not just in health centers and

Adapted from: Comprehensive condom programming: A strategic response to HIV/AIDS. (2008).

UNFPA: New York. Internet document, available at: http://www.unfpa.org/hiv/programming.htm

2

8

pharmacies, but also in non-traditional distribution points such as hair salons,

barber shops, vending machines, night clubs, youth centres, etc.. It requires the

collaboration of the private and public sector, also leveraging the social marketing

sector to reach specific populations and create demand for male and female

condoms. And it requires a consistent and affordable supply to ensure that

individuals can access condoms whenever and wherever they are needed.

What role can service providers play in CCP?

As a service provider, you have a key role to play in CCP. You are the gatekeeper to

condom users and you also can play an important role to advocate to your leaders

for the implementation and continued momentum of CCP. Whilst service providers

may e seen as gate-keepers, this is to a very limited extent. Community leaders are the

ones largely play the gate-keeping role.

Importantly, your specific role is to raise awareness on STI/HIV and unintended

pregnancy risk, condom as a dual protection method, risk of HIV/STI, make goodquality condoms readily available, teach people how to use condoms consistently

and correctly, work to eradicate the social stigma associated with male and female

condoms, and advocate for the integration of condoms into other HIV prevention

and SRH programmes.

Talking about condoms is not always easy for potential condom users. We

recommend the following five actions to create an enabling environment:

Step 1. Create an interactive, client-friendly environment.

Step 2. Ensure that high-quality condoms are always available.

Step 3. Counsel users about correct and consistent condom use in a supportive

manner.

Step 4. Reach out to the community.

Step 5. Check progress.

Step-by-Step Strategic Approach to Comprehensive Condom

Programming

Steps in Strategic Comprehensive Condom Programming may vary from country to

country, depending on many factors, from the local epidemiology of STIs,

distribution infrastructure, cultural context to budgetary issues. However, the

process of designing and implementing a strategy has many common features,

which are described below.

Your government is using the CCP process to strengthen your country’s condom

?programmining. These are the steps that they may be following. Training service

9

delivery providers like yourself falls under step 7, and your work with clients is a

part of step 8. However, you can also play a role in the other steps by advocating for

implementation and momentum around CCP

Step 1: Establish a National Condom Task Team (NCTT) Lets be consistent in the use

of terms. The RNA tool call this committee National Condom Support Team, NCST.

Step 2: Undertake a Situation Analysis

Step 3: Develop a Comprehensive and Integrated National Male/Female Condom

Strategy and cost each component

Step 4: Develop a 5 year Strategic Plan

Step 5: Develop a Commodity Security Plan

Step 6: Mobilize Resources

Step 7: Develop and implement a Human Resource capacity strengthening plan

Step 8: Develop a condom promotion plan to increase access and utilization

Step 9: Advocacy and Media

Step 10: Monitor programme implementation routinely and evaluate outcomes

Five Steps for Increasing Demand for and Supply of Condoms

To encourage people to use condoms, programmes need to raise awareness of

HIV/STI risks, make good-quality condoms readily available, teach people how to

use condoms correctly, work to eradicate the social stigma associated with

condoms, and advocate for HIV prevention and condom use in the community.3 The

following five-step process may be used to increase the demand for and supply of

condoms:

Step 1. Make the outlet client-friendly.

Step 2. Ensure that high-quality condoms are always available.

Step 3. Counsel clients about condoms.

Step 4. Reach out to the community.

Step 5. Check progress.

Condom Programming for HIV Prevention: A Manual for Service Providers. (2003). UNFPA, WHO &

PATH: New York

3

10

Overview

Condom Programming4

I think the overview needs to come much earlier at the beginning of the chapter.

What is Condom Programming? Condom programming is an integrated approach

consisting of demand, supply and support functions that was created to expand

access and help prevent the spread of STIs, including HIV. To give the condom

higher visibility and impact, the World Heath Organization’s (WHO) Global

Programme on AIDS (GPA) developed and embraced comprehensive condom

programming in April 1988. Before then, the condom was generally viewed as an

unpopular, not-so-effective family planning method stigmatized because of its

association with sex outside of marriage. As a family planning device, providers did

not consider the condom a “modern” method and consequently relegated it to the

lowest rungs of the contraceptive ladder.

While negative attitudes are still prevalent today, condom programming is now

recognized as one of the most significant primary approaches in the fight against

HIV. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the agency within

the UNAIDS system responsible for condom programming: “Condoms are

universally recognized as one of the most effective ways to prevent HIV and other

sexually transmitted infections.” 5

Comprehensive condom programming and the provision of testing and conselling

services go together: they arise out of the basic logic of prevention which is: know

your status and take action. Routine testing and counselling (TC), which helps

identify HIV positive people who may need antiretroviral treatment, is a valuable

companion intervention that justifies condoms as a rational STI/HIV prevention

choice, even in stable sexual relationships. Successful condom promotion requires

easy access to TC. Why? Because healthcare personnel must be able to educate

couples regarding when to stop using condoms should they adopt a long-term

strategy of faithfulness to an uninfected partner. Without access to TC, couples in a

world affected by HIV/AIDS have no way of knowing whether, or how, to stop using

condoms and start childbearing with a clear conscience and free of fear. Please take

note that there have been a deliberate shift from emphasis on VCT to routine offer of

Testing and Counselling (TC). Most countries have taken up routine offer of TC as a

strategy for increasing the number of people to be tested for HIV.

Condom programming operates in the real world where STIs and HIV infections

occur. Comprehensive condom programming recognizes that the typical human life

Source: Friel, P. (23 September 2007 Draft). Condom Programming: An Intergral Part of HIV

Prevention and Treatment. UNFPA: In Press.

5 HIV Prevention Now, Programme Briefs, No. 6, Condom Programming for HIV Prevention, June

2002.

4

11

cycle in diverse communities requires different tactics for different people at

different times. When working properly, condom programming involves a range of

activities that embrace political and financial issues as well as programmatic

(operational and managerial) priorities at all levels.

Political leadership: condom programming requires high-level support for an

integrated public health, i.e., evidence-based, approach based on STD epidemiology.

All too often, national authorities fail to recognize, and respond to the fact that

condom-related stigma casts a long shadow over their work. This adversely affects

even evidence-based and age-appropriate interventions for reproductive health and

disease prevention. Unwavering political leadership must confront stigma and

continually remind stakeholders that proper and consistent condom use can save

lives, protect families, ?strengthen the economy and help secure the future of the

community.

Financial support: donors and governments must realize that even the best

designed and politically-supported condom programmes will fail without adequate

and continuous long-term financial support. This factor profoundly affects every

other priority.

Programmatically responsive: access to, and use of, condoms helps protect a wide

range of young, middle-aged and older people in society. These include first-time

sexually-active youth, women engaging in intergenerational or transactional sex, sex

workers and their clients, men who have sex with men, injecting drug users and

their partners and discordant couples, including monogamous married women

whose husbands bring home infections, e.g., after working abroad. This is a complex

equation. Because condom programming must serve different socio-economic

geographic and cultural target audiences, it requires that different sectors and

agencies working in urban and rural areas mount a coordinated, adequately-funded

national response. Again, political leadership is needed to assure that integrated,

evidence-based approaches are supported and that stigma is countered with

wisdom and courage.

Step-by-Step Strategic Approach to Comprehensive Condom

Programming This section appears to be a repetition of what has

been explained above.

To be strategic, condom programming must:

Recognize complimentarity between male and female condoms;

Be integrated and optimise use of different entry points in RH and HIV

prevention settings;

Segment population including young people; and

Appropriately utilise public, social marketing and private sector mix.

12

The goal of comprehensive condom programming should be to increase the number

of protected sex acts that will reduce incidence of unwanted pregnancy and STIs

including HIV.

Steps in Strategic Comprehensive Condom Programming may vary from country to

country, depending on many factors, from the local epidemiology of STIs,

distribution infrastructure, cultural context to budgetary issues. However, the

process of designing and implementing a strategy has many common features,

which are described below. A number of publications are available to guide you and

explain how this process has worked in various countries.

Step 1: Establish a National Condom Task Team (NCTT)

Step 2: Undertake a Situation Analysis

Step 3: Develop a Comprehensive and Integrated National Male/Female Condom

Strategy and cost each component

Step 4: Develop a 5 year Strategic Plan

Step 5: Develop a Commodity Security Plan

Step 6: Mobilize Resources

Step 7: Develop and implement a Human Resource capacity strengthening plan

Step 8: Develop a condom promotion plan to increase access and utilization

Step 9: Advocacy and Media

Step 10: Monitor programme implementation routinely and evaluate outcomes

Cost-effectiveness of the female condom6

Before talking about female condom research we need to introduce the female condom

and say what it is and its role in STI/HIV prevention.

Perhaps the most important new research to emerge about the female condom is

that it may be cost-effective to provide the female condom in reproductive health

programmes. Particularly in target groups that practise high-risk behaviours, female

condom programmes can even be cost-saving. Family Health International (FHI),

The Female Health Company (FHC), Health Strategies International (HSI),the

Institute of Health Policy Studies at the University of California, the London School

of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Population Services International (PSI) and

UNAIDS have all been engaged in research to measure the cost-effectiveness of

introducing the female condom into reproductive health programmes. The findings

6

Source: The Female Condom: A guide for planning and programming. (2000). WHO & UNAIDS.

13

from these various studies indicate that the female condom can be a cost-effective

addition to prevention programmes. This cost-effectiveness is maximized under the

following conditions:

Targeting in high-prevalence areas

Not surprisingly, the female condom becomes increasingly cost-effective and even

cost-saving as the level of risk of STIs and HIV/AIDS increases among users and

their partners. By targeting sex workers and other women and men with multiple

sexual partners, the female condom can be not only cost-effective but also costsaving to the health care system.

Providing the female condom in combination with the male condom

The purpose of introducing the female condom into national reproductive health

programmes is to increase the number of protected sexual acts, decrease the

incidence of STIs and HIV/AIDS and unintended pregnancy, and thus decrease the

associated costs. Because the female condom has a higher unit cost, the female

condom should be targeted at populations that already have ready access to the

male condom or are not able to use the male condom consistently. Shall we simplify

this? It is difficult to understand. By focusing on these groups, female condom use

increases the number of protected sexual acts without necessarily decreasing male

condom use.

Incremental increase in protection

The experience from family planning programmes over many years highlights the

importance of simply expanding people’s choice. The addition of contraceptive

methods to the options available to people produces incremental increases in

contraceptive prevalence. Similarly, the addition of the female condom to the

options for safer sexual behaviour has produced incremental increases in protected

sexual acts.

Planning strategically for the introduction of the female condom7

Before activities begin for the introduction of the female condom into a country or a

programme, it is important to design a comprehensive introduction strategy. In fact,

the first question that needs to be asked is whether there is a need to introduce the

female condom, or whether priority should be placed on improving the provision of

currently available methods. The above statement in my view could be misleading.

The only other available dual protection method is the male condom. I think the female

condom should be introduced anyway, even when the male condom programme is

working well, so as to widen choice. The male condom may not be able to address the

STI/HIV prevention needs for everybody, e.g. those with latex allergies, those whose

partners refuse to wear the male condom etc. Evidence from experiences with

contraceptive introduction demonstrates that the addition of a new method in itself

does not automatically lead to increased choice. Service delivery systems do not

7

Source: The Female Condom: A guide for planning and programming. (2000). WHO & UNAIDS.

14

always have the capability to provide a new method with the appropriate care.

Although small-scale studies and introductory trials of new methods usually offer

high-quality services, weaknesses in training, counselling, supervision and logistics

management often make it difficult to sustain quality services when the method is

introduced on a larger scale.

Factors such as confusion on the part of providers and consumers as well as failure

to take into account their beliefs, attitudes, concerns and experiences can also

counteract the potential that new methods have for expanding contraceptive

options for clients. Kindly explain what confusion this is, and where it could arise

from. Costs, side-effects, the manner in which clients are treated in clinics and many

other personal, cultural and socio-economic factors affect the demand for and

acceptability of a contraceptive.

In developing an introduction strategy it is important to think strategically, and see

the female condom as one of a range of methods that an individual or couple could

use to prevent pregnancy and/or STIs, including HIV.

In order to do this, programme managers must consider the needs of potential

users, the services and technologies currently available and the current capability of

the service delivery system, when planning female condom introduction activities.

Assessing and addressing all of these dimensions is essential to the success of

introductory activities. In addition, these issues cannot be seen in isolation, but must

be considered within a broader social context, including the sociocultural

environment, the broader reproductive health status and needs of individuals, and

the political and resource environments.

This strategic approach to introduction is described in more detail in WHO’s “A

guide for assessing strategies to broaden contraceptive choice and improve quality

of care”(see Section 8). In this approach, any country thinking about introducing any

contraceptive method should conduct a multi-faceted assessment of the situation

through a participatory process.

The steps in planning this process are outlined below.

1. Develop a national team to coordinate activities.

2. Organize a stakeholders’ meeting to put the female condom on the public

health agenda and gain a mandate for developing a strategic plan.

3. Assess user needs and service capabilities and currently available methods

and services. Outline the context for the introduction of the female condom.

4. Draft a strategic document. Use the document to obtain consensus from all

stakeholders.

5. Implement pilot intervention with monitoring and evaluation.

6. Feedback, revision and going to scale – expand programme on broader scale.

15

Steps to introduce and integrate the female condom into

reproductive health programmes8

1. Strategy for integration. Develop a strategy on how best to integrate the

female condom into existing programme activities.

2. Programme costing.

3. Select the target audience(s). Determine potential populations for

promotion and subdivide them into different potential target audiences.

4. Gather information from the target audience. Assess the existing

perceptions of the female condom among the target group.

5. Advocacy with the community and consolidation of support. Meet with

the community to gain their support for the introduction of the female

condom.

6. Develop distribution strategy to reach target group.

7. Develop communication strategies and materials. Develop IEC materials

and approaches based on information and insights gained from focus groups

and individual interviews.

Training. Identify and train resource people who can support behaviour

change. Produce reference materials to reinforce the training of resource

people, including information about where they can go to ask for assistance.

8. Monitoring and evaluation. Ensure that a monitoring and evaluation plan is

in place.

These steps may be fine for introducing the FC. They however may not exactly

help us to integrate FC into existing programmes. With integration we need to

meet with those running different RH and HIV prevention programmes, agree

on entry points, adapt of materials, train service provider in other programme

areas, do joint monitoring of programmes etc

Barriers

There are many impediments to effective condom programming. To understand

how they work and how to overcome them, one must consider them in terms of

their personal, financial, political, national, global and health systems aspects. While

some of these impediments may be amenable to operational solutions such as

improved logistics and coordination, others are deeply rooted in society’s political,

social, cultural, legal and economic systems. Developing solutions to all of them

would be ideal. However, doing so remains difficult because the barriers are

formidable and, in many ways, interconnected. In this document, we will briefly

discuss personal barriers are they are most relevant for our work.

Personal barriers

Complaints about the physical qualities of male condoms are well known. One need

not have ever used condoms, or even seen one, to understand that they are

associated with an intimate and taboo-laden activity: sex. Many would-be users

8

Source: The Female Condom: A guide for planning and programming. (2000). WHO & UNAIDS.

16

complain that they are “greasy,” unattractive, often have a rubbery smell and

interfere with the natural “spontaneity” of the sex act. They are the butt of jokes in

every language. They form a layer of insulation between the penis and the vagina

and, even after sensitive negotiations their use can still somehow imply a lack of

trust. To actually be used they have to be physically available at the moment of

intercourse (but often are not) and potential users must both be sufficiently

informed, sober and motivated.

17

Chapter II: Male and Female Anatomy

Objectives

To provide information on the anatomy and physiology (functions) of the

male and female reproductive systems

Key Points

Male Sexual and Reproductive System9

The purpose of the organs of the male sexual and reproductive system is to

perform the following functions:

1. To produce, maintain and transport sperm (the male reproductive cells) and

protective fluid (semen)

2. To discharge sperm within the female reproductive tract during sex

3. To produce and secrete male sex hormones responsible for growth,

maturation and maintaining the male reproductive system and functions

4. To perform the procreation function

Unlike the female reproductive system, most of the male reproductive system is

located outside of the body. These external structures include the penis, scrotum,

and testicles and can produce pleasurable sensation when stimulated.

The Female Sexual and Reproductive System10

The female sexual and reproductive system is designed to carry out several

functions:

1. It produces the female egg cells necessary for reproduction, called the ova or

oocytes. The system is designed to transport the ova to the site of

fertilization.

2. Conception, the fertilization of an egg by a sperm, normally occurs in the

upper part of the fallopian tubes.

3. The next step for the fertilized egg is to implant into the walls of the uterus,

beginning the initial stages of pregnancy. If fertilization and/or implantation

Source: The Male Reproductive System. (2008). WebMD. Internet document, available on:

http://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/guide/male-reproductive-system

10 Source: The Female Reproductive System. (2008). WebMD. Internet document, available on:

http://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/guide/your-guide-female-reproductive-system

9

18

does not take place, the system is designed to menstruate (the monthly

shedding of the uterine lining).

4. In addition, the female reproductive system produces female sex hormones

that maintain the reproductive cycle.

5. Pregnancy and breastfeeding functions.

Like male sexual and reproductive organs, the female organs can produce

pleasurable sensation when stimulated.

Overview

The following sections will present a detailed discussion of the male and female

organs relevant for sexual activity and condom use.

The Male Sexual and Reproductive System I don’t think we need to

repeat these points.

The purpose of the organs of the male reproductive system is to perform the

following functions:

1. To produce, maintain and transport sperm (the male reproductive cells) and

protective fluid (semen)

2. To discharge sperm within the female reproductive tract during sex

3. To produce and secrete male sex hormones responsible for maintaining the

male reproductive system

Unlike the female reproductive system, most of the male reproductive system is

located outside of the body. These external structures include the penis, scrotum,

and testicles.

Insert Diagrams

Penis: This is the male organ used in sexual intercourse.

It has 3 parts:

the root, which attaches to the wall of the abdomen;

the body, or shaft; and

the glans, which is the cone-shaped part at the end of the penis.

The glans, also called the head , is covered with a loose layer of skin called foreskin.

(This skin is sometimes removed in a procedure called circumcision.)

19

The opening of the urethra, the tube that transports semen (also known as cum) and

urine, is at the tip of the penis. The penis also contains a number of sensitive nerve

endings. The body of the penis is cylindrical in shape and consists of 3 circular

shaped chambers. These chambers are made up of special, sponge-like tissue. This

tissue contains thousands of large spaces that fill with blood when the man is

sexually aroused. As the penis fills with blood, it becomes hard and erect, which

allows for penetration during sexual intercourse.

The skin of the penis is loose and elastic to accommodate changes in penis size

during an erection. Semen, which contains sperm (reproductive cells), is expelled

(ejaculated) through the end of the penis when the man reaches sexual climax

(orgasm). When the penis is erect, the flow of urine is blocked from the urethra,

allowing only semen to be ejaculated at orgasm.

Scrotum: This is the loose pouch-like sac of skin that hangs behind the penis. It

contains the testicles (also called testes), as well as many nerves and blood vessels.

The scrotum acts as a "climate control system" for the testes. For normal sperm

development, the testes must be at a temperature slightly cooler than body

temperature. Special muscles in the wall of the scrotum allow it to contract and

relax, moving the testicles closer to the body for warmth or farther away from the

body to cool the temperature.

Testicles (testes): These are two oval organs about the size of large olives that lie in

the scrotum, secured at either end by a structure called the spermatic cord. The

testes are responsible for making testosterone, the primary male sex hormone, and

for generating sperm. Within the testes are coiled masses of tubes called

seminiferous tubules. These tubes are responsible for producing sperm cells.

The internal organs of the male reproductive system, also called accessory organs,

include the following:

Epididymis: The epididymis is a long, coiled tube that rests on the backside of each

testicle. It transports and stores sperm cells that are produced in the testes. It also is

the job of the epididymis to bring the sperm to maturity, since the sperm that

emerge from the testes are immature and incapable of fertilization. During sexual

arousal, contractions force the sperm into the vas deferens.

Vas deferens: The vas deferens is a long, muscular tube that travels from the

epididymis into the pelvic cavity, to just behind the bladder. The vas deferens

transports mature sperm to the urethra, the tube that carries urine or sperm to

outside of the body, in preparation for ejaculation.

Ejaculatory ducts: These are formed by the fusion of the vas deferens and the

seminal vesicles (see below). The ejaculatory ducts empty into the urethra.

Urethra: The urethra is the tube that carries urine from the bladder to outside of

the body. In males, it has the additional function of ejaculating semen when the man

20

reaches orgasm. When the penis is erect during sex, the flow of urine is blocked

from the urethra, allowing only semen to be ejaculated at orgasm.

Seminal vesicles: The seminal vesicles are sac-like pouches that attach to the vas

deferens near the base of the bladder. The seminal vesicles produce a sugar-rich

fluid (fructose) that provides sperm with a source of energy to help them move. The

fluid of the seminal vesicles makes up most of the volume of a man's ejaculatory

fluid, or ejaculate.

Prostate gland: The prostate gland is a walnut-sized structure that is located below

the urinary bladder in front of the rectum. The prostate gland contributes additional

fluid to the ejaculate. Prostate fluids also help to nourish the sperm. The urethra,

which carries the ejaculate to be expelled during orgasm, runs through the centre of

the prostate gland.

Bulbourethral glands: Also called Cowper's glands, these are pea-sized structures

located on the sides of the urethra just below the prostate gland. These glands

produce a clear, slippery fluid that empties directly into the urethra. This fluid

serves to lubricate the urethra and to neutralize any acidity that may be present due

to residual drops of urine in the urethra.

How Does the Male Reproductive System Function?

The entire male reproductive system is dependent on hormones, which are

chemicals that regulate the activity of many different types of cells or organs. The

primary hormones involved in the male reproductive system are follicle-stimulating

hormone, luteinizing hormone, and testosterone.

Follicle-stimulating hormone is necessary for sperm production (spermatogenesis)

and luteinizing hormone stimulates the production of testosterone, which is also

needed to make sperm. Testosterone is responsible for the development of male

characteristics, including muscle mass and strength, fat distribution, bone mass,

facial hair growth, voice change and sex drive.

Human sexuality is how people experience and express themselves as sexual beings.[1]

The study of human sexuality encompasses an array of social activities and an

abundance of behaviors, actions, and societal topics. Biologically, sexuality can

encompass sexual intercourse and sexual contact in all its forms, as well as medical

concerns about the physiological or even psychological aspects of sexual behaviour.

Sociologically, it can cover the cultural, political, and legal aspects; and philosophically,

it can span the moral, ethical, theological, spiritual or religious aspects.

Human sexual behavior encompasses the search for a partner or partners, interactions

between individuals, physical, emotional intimacy, and sexual contact. Some cultures

21

discriminate against sexual contact outside of marriage. Eextramarital sexual activity is

perceived as pervasive. Unprotected sex may result in unwanted pregnancy or sexually

transmitted diseases. In some areas, sexual abuse of individuals is prohibited by law and

considered against the norms of society.

Heterosexuality involves individuals of opposite sexes. Different sexual practices are

limited by laws in many places. In some countries, mostly those where religion has a

strong influence on social policy, marriage laws serve the purpose of encouraging

people to only have sex within marriage. Sodomy laws were seen as discouraging

same-sex sexual practices, but may affect opposite-sex sexual practices. Laws also ban

adults from committing sexual abuse, committing sexual acts with anyone under an

age of consent, performing sexual activities in public, and engaging in sexual activities

for money (prostitution). Though these laws cover both same-sex and opposite-sex

sexual activities, they may differ with regards to punishment, and may be more

frequently (or exclusively) enforced on those who engage in same-sex sexual activities.

Homosexuality. Same-sex sexuality involves individuals of the same sex. It is possible

for a person whose sexual identity is mainly heterosexual to engage in sexual acts with

people of the same sex. For example, mutual masturbation in the context of what may

be considered normal heterosexual teen development. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual

people who pretend to be heterosexual are often referred to as being closeted, hiding

their sexuality in "the closet". "Closet case" is a derogatory term used to refer to people

who hide their sexuality. Making that orientation (semi-) public can be called "coming

out" in the case of voluntary disclosure or "outing" in the case of disclosure by others

against the subject's wishes. Among some communities (called "men on the DL" or

"down-low"), same-sex sexual behavior is sometimes viewed as solely for physical

pleasure. Men on the "down-low" may engage in sex acts with other men while

continuing sexual and romantic relationships with women.

Gender identity is a person's own sense of identification as male or female. The term is

intended to distinguish this psychological association, from physiological and

sociological aspects of gender. Gender identity is how one personally identifies

their/hir/her/his/yo's gender regardless of their sex characteristics. It does not have to

be either man or woman, but can be a combination of feminine, masculine and

androgynous feelings.

Sexual abuse. Sexual activity can also encompass sexual abuse - that is, coercive or

abusive use of sexuality. Examples include: rape, lust murder, child sexual abuse, and

zoosadism (animal abuse which may be sexual in nature), as well as (in many countries)

certain non-consensual paraphilias such as frotteurism, non-consensual exhibitionism

and voyeurism. Sexual abuse can occur amongst adults, children, adults and children

and amongst both (or all) sexes and genders.

22

The Female Reproductive System I think we could do without this

repetition. Alternatively, you may consider presenting the

information in text boxes if you feel the information requires

emphasis.

The female reproductive system is designed to carry out several functions. It

produces the female egg cells necessary for reproduction, called the ova or oocytes.

The system is designed to transport the ova to the site of fertilization. Conception,

the fertilization of an egg by a sperm, normally occurs in the fallopian tubes. The

next step for the fertilized egg is to implant into the walls of the uterus, beginning

the initial stages of pregnancy. If fertilization and/or implantation (pregnancy) does

not take place, the system is designed to menstruate (the monthly shedding of the

uterine lining). In addition, the female reproductive system produces female sex

hormones that maintain the reproductive cycle.

What Parts Make up the Female Anatomy?

The female reproductive system includes parts inside and outside the body.

Insert Diagrams

The function of the external female reproductive structures (the genitals) is twofold:

To enable sperm to enter the body and to protect the internal genital organs from

infectious organisms. The main external structures of the female reproductive

system include:

Labia majora: The labia majora enclose and protect the other external reproductive

organs. Literally translated as "large lips," the labia majora are relatively large and

fleshy. The labia majora contain sweat and oil-secreting glands. After puberty, the

labia majora are covered with hair.

Labia minora: Literally translated as "small lips," the labia minora can be very small

or up to 2 inches wide. They lie just inside the labia majora, and surround the

openings to the vagina (the canal that joins the lower part of the uterus to the

outside of the body) and urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the

outside of the body).

Bartholini's glands: These glands are located besides the vaginal opening and

produce a fluid (mucus) secretion that provides natural lubrication during sex,

provided the woman has been sexually aroused.

Clitoris: The two labia minora meet at the clitoris, a small, sensitive protrusion that

is comparable to the penis in males. The clitoris is covered by a fold of skin, called

the prepuce, which is similar to the foreskin at the end of the penis. Like the penis,

the clitoris is very sensitive to stimulation and can become erect.

23

The internal reproductive organs in the female include:

Vagina: The vagina is a canal that joins to the cervix (the lower part of uterus) to the

outside of the body. It also is known as the birth canal. This is the organ that

receives the penis during intercourse.

Uterus (womb): The uterus is a hollow, pear-shaped organ that is the home to a

developing foetus. The uterus is divided into two parts: the cervix, which is the

lower part that opens into the vagina, and the main body of the uterus, called the

corpus. The corpus can easily expand to hold a developing baby. A channel through

the cervix allows sperm to enter and menstrual content to exit.

Ovaries: The ovaries are small, oval-shaped glands that are located on either side of

the uterus. The ovaries produce eggs and hormones after puberty until menopause.

Fallopian tubes (oviduct): These are narrow tubes that are attached to the upper

part of the uterus and serve as tunnels for the ova (egg cells) to travel from the

ovaries to the uterus. Conception, the fertilization of an egg by a sperm, normally

occurs in the fallopian tubes. The fertilized egg then moves to the uterus, where it

implants into the lining of the uterine wall.

Breasts: The mammary glands are in the breasts that produce and secrete milk

during the lactation process to feed the newborn. During pregnancy, high blood

estrogen and progesterone levels stimulate lactation. The corpus luteum produces

these hormones during early pregnancy; the placenta takes over later. The

hormones stimulate the ducts and glands in the breasts, enlarging the breasts.

What Happens During the Menstrual Cycle?

Females of reproductive age (from around 10 to 50 years) experience cycles of

hormonal activity that repeat at about one-month intervals. (Menstru means

"monthly"; hence the term menstrual cycle.) With every cycle, a woman's body

prepares for a potential pregnancy, whether or not that is the woman's intention.

The term menstruation refers to the periodic shedding of the uterine lining.

The average menstrual cycle takes about 28-32 days and occurs in phases: the

follicular phase, the ovulatory phase (ovulation), and the luteal phase.

There are four major hormones (chemicals that stimulate or regulate the activity of

cells or organs) involved in the menstrual cycle: follicle-stimulating hormone,

luteinizing hormone, estrogen, and progesterone.

Follicular Phase of the Menstrual Cycle

This phase starts on the first day of your period. During the follicular phase of the

menstrual cycle, the following events occur:

24

Two hormones are released from the brain and travel in the blood to the

ovaries.

The hormones stimulate the growth of about 15-20 eggs in the ovaries each

in its own "shell," called a follicle.

These hormones also trigger an increase in the production of the female

hormone estrogen.

As estrogen levels rise, like a switch, it turns off the production of folliclestimulating hormone.

As time passes, one follicle in one ovary becomes dominant and continues to

mature, while others stop growing and die.

Ovulatory Phase of the Menstrual Cycle

The ovulatory phase, or ovulation, starts about 14 days after the follicular phase

started. The ovulatory phase is the midpoint of the menstrual cycle, with the next

menstrual period starting about 2 weeks later. During this phase, the following

events occur:

The rise in estrogen from the dominant follicle triggers a surge in the amount

of hormones produced by the brain.

This causes the dominant follicle to release its egg from the ovary.

As the egg is released (a process called ovulation) it is captured by finger-like

projections on the end of the fallopian tubes (fimbriae).

Also during this phase, there is an increase in the amount and thickness of

mucous produced by the lower part of the uterus (cervix). I thought the

mucous decreases in thickness or becomes thinner to allow easier passage of

sperm. If a woman were to have intercourse during this time, the thick

mucus captures the man's sperm, nourishes it, and helps it to move towards

the egg for fertilization.

Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle

The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle begins right after ovulation and involves the

following processes:

Once it releases its egg, the empty follicle develops into a new structure

called the corpus luteum.

This structure releases the hormone progesterone. Progesterone prepares

the uterus for a fertilized egg to implant.

If intercourse has taken place and a man’s sperm has fertilized the egg

(conception), the fertilized egg (embryo) will travel through the fallopian

tube to implant in the uterus. The woman is now considered pregnant.

If the egg is not fertilized, it passes through the uterus. Not needed to support

a pregnancy, the lining of the uterus breaks down and sheds, and the next

menstrual period begins.

25

How Many Eggs Does a Woman Have?

The vast majority of the eggs within the ovaries steadily die, until they are depleted

at menopause. At birth, there are approximately 1 million eggs; and by the time of

puberty, only about 300,000 remain. Of these, 300 to 400 will mature and be

ovulated during a woman's reproductive lifetime. The eggs continue to degenerate

during pregnancy, with the use of birth control pills, and in the presence or absence

of regular menstrual cycles.

26

Anal Sex11

As in the case with penis, vagina, testes, urethral etc, shall we also start with functions of

the anus and rectum like we did in previous passages. The anus is the opening to the

lower end of the digestive tract (in men and women) and is surrounded by two sets of

muscles called the anal sphincters. A person can learn to control the contractions of the

outer sphincter. The anal opening leards into the short anal canal and the larger

rectum. Perineal muscles support the area around the anus and are in close contact

with the bulb of the penis in the male and othe outer portion of the vagina in the feale.

All of these tissues are well supplied with blood vessels and nerves. This makes the

anal-penile intercourse pleasureable for some individuals, but also makes the anal

cavity highly susceptible to HIV.

The inner third of the anal canal is less ensitive to touch than the outer two-thirds, but is

more sensitive to preassure. The rectum is a curved tube about eight or nine inches

long and has the capacity, like the anus, to expand.

One form of anal intercourse involves the insertion of an object into the anus. The

object may be a finder, penis, dildo, or other objects. Some people engage is “fisting”

which is the insertion of the hand and sometimes part of the forearm into the anus and

rectum.

For some, the pleasure derived from penetration of the anus is both physical and

psychological. Psychological satisfaction may be derived by the feelings of dominance

and submission produced in the particpants. Fantasy is often an important factor in

achieving satisfaction. The stimulation of the nerve endings in the tissues and muscles,

the bulb of the penis, and connections to the vagina; the feeling of fullness in the

rectum; and the rubbing against the prostate gland in the male, create physical

pleasure in many. Various objects may be used to stimulate the anus.

The anus is also used sexually (in males and females) in ways that do not involve

penetration. The rubbing of the external sphincter and the flexing of the muscle are

common. Anilingus (rimming) – or the kissing, licking, sucking and insertion of the

tongue into the anus is common.

Contrary to the popular belief, anal sex is not an activity exclusive to the male

homosexual. In some societies, heterosexual couples engage in anal sex in order to

protect the “vaginal virginity” of the female partner, which may be socio-culturally

appropriate. Anal sex is at times practiced as means of contraception. Some studies

report that 47% of predominantly heterosexual men and 61% of the women have tried

anal intercourse. Thirteen percent of married couples reported having anal intercourse

at least once a month. Approximately 37% of both men and women have practice oral11

Bullough VL & Bullough B. (1994). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis.

27

anal contact.

Certain precautions must be followed if practicing anal sex. Penetration should be done

slowly and carefully by a penis or a soft rubber object that has no sharp edges or points.

Anything inserted into the anus should be well covered by a water-based lubricant and

a condom. The pain of insertion can be overcome by the inserted by practicing

relaxation techniques and, if done properly, there should be no tearing of the soft anal

tissues. Positioning of the inserted object is important because of the curve of the

rectum. Fisting is an activity that should be practiced with great care (if at all). Few

people are capable of relaxing enough to accommodate something as big as an arm in

their anus and there is real dnages of damage to the delicate rectal tissues.

Disease-causing orgasms can be transmitted during anal sex. These include HIV,

syphyilis, gonnorhea, nongonococcal urethritis, herpes, anal warts, hepatitis, and

various organisms that cause intestinal infections. They can also be transmitted from

anus to mouth or to vagina if a penis or dildo is not thoroughly cleaned.

Anilingus (rimming) is another activity that presents an avenue for both pleasure but

also disease transmission.

28

Chapter III: Reproductive Health

Objectives

To introduce basic issues related to reproductive health, sexual health and

reproductive rights.

To clarify concepts such as:

o Family planning,

o Maternal health including antenatal care, child birth and postnatal

care

o Gender-based violence

o Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and

o Voluntary counselling and testing.

Key Points

Reproductive Health

Reproductive health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and

not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the

reproductive system and to its functions and processes for all people.12

Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and

safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide

if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this last condition is the right of men and

women to be informed and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable

methods of family planning of their choice, as well as other methods of their choice for

regulation of fertility which are not against the law, and the right of access to

appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through

pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy

infant…13

Sexual Health

Sexual health has always been closely linked with reproductive health, particularly

since the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994,

which defined RH as incorporating sexual health. However, recently this

12

13

UN International Conference on Population and Development (1994). UN. Cairo, Egypt.

Ibid.

29

conceptualization has been advanced, with the recognition that sexual health is

broader and more encompassing than reproductive health.14

Rather than being a component, sexual health should be seen as a necessary

underlying condition for reproductive health, while at the same time being relevant

throughout the life span and not only during the reproductive years.15

Sexual and reproductive rights are complicated for people living with HIV who

know their status as they have the additional stress of disclosing their HIV status in

new relationships, which can lead to stigma and discrimination. Once people are

found to be HIV-positive, it is often assumed both by them and by the world at large

that their sex lives should cease. Yet there is no scientific reason why this should be

the case. Many HIV-positive women in discordant relationships have continued to

have sex with their partners for many years, whilst ensuring that their partners

remain HIV-negative through using condoms. The world is also encouraged by the

new research showing antiretroviral treatment may be used effectively for

prevention. Indeed, sexual pleasure is a fundamental part of all our lives and sexual

intimacy is known to play a valuable part in maintaining psychological wellbeing.

We are all sexual beings whether or not we choose to engage in sex. To pretend

otherwise is to deny a fundamental part of our existence as human beings.16

The field of sexual health encompasses a range of issues, including:

STIs, including HIV, and reproductive tract infections (RTIs);

Unintended pregnancy and unsafe abortion;

Infertility;

Sexual well-being of both HIV affected and infected communities (including

sexual satisfaction, pleasure and dysfunction);

Violence related to gender and sexuality;

Certain aspects of mental health;

Impact of physical disabilities and chronic illnesses on sexual health;

Reproductive Rights

Around the world, every minute 380 women get pregnant, 190 women face an

unintended pregnancy, 110 women face a pregnancy-related problem, 40 women

undergo an unsafe abortion, 30 are injured or disabled, and 1 woman dies17.

Butler, P.A. (2004). Sexual Health – A New Focus for WHO. Progress in Reproductive Health. WHO.

No. 67. (p. 2).

15 Butler, P.A. (2004). Sexual Health – A New Focus for WHO. Progress in Reproductive Health. WHO.

No. 67. (p. 2).

16 Sophie Dilmitis, World YWCA.

17 CHEDRES. (2009). Safe Motherhood. Internet document, available at:

http://www.chedres.org/safemotherhood/

14

30

Reproductive rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and

individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their

children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the

highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. They also include the right of all

to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and

violence.

PLHIV should have the same rights as people who are not infected with HIV. In an

effort to control the epidemic, many governments have passed laws that criminalise

the transmission of HIV. Criminalisation of transmission can happen by creating

laws specifically aimed at HIV transmission. For example, a person could be charged

with the act of transmitting HIV to another person. Or second, prosecutors can use

existing laws to prosecute the transmission of HIV. For example, a person could be

charged with ‘reckless endangerment’ for having sex with their partner even if there

is no law that specifically makes it a criminal act to transmit HIV18.

According to Planned Parenthood, 58 countries worldwide have laws that

criminalise HIV or use existing laws to prosecute people for transmitting the virus.

Another 33 countries are considering similar legislation.

Criminalising HIV has further repercussions for women, especially pregnant women

who in many countries are now being prosecuted for endangering the foetus. As

such, women whose babies are born HIV-positive could be prosecuted for

transmitting HIV to their newborn. And this despite the fact that even when

antiretroviral treatment is used during the perinatal period, there is stills a 1-2%

chance of transmission! As we can see, women are prime targets for this as pregnant

women are often the first to be tested when they access reproductive health

services. All of this is happening in a time where only a quarter of HIV-positive

pregnant women in poorer countries receive antiretroviral therapy to prevent

perinatal transmission. Women are increasingly vulnerable to unfair prosecution in

the environment of routine opt-out testing. Opt-out testing is defined as performing

HIV screening after notifying the patient that 1) the test will be performed and 2)

the patient may elect to decline or defer testing. Assent is inferred unless the

patient declines testing.

Most people spread HIV when they do not know their status. Furthermore these

laws drive people underground and further away from voluntary counseling and

testing as these laws place all the onus of responsibility on the HIV positive person.

Criminalisation further discourages open dialogue around HIV and AIDS.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “All human beings are born

free and equal in dignity and rights.” This idea provides a foundational principle for

all advocacy efforts against the criminalisation of HIV. Christian organisations

18

Aziza Ahmed and featured in ICW News Issue 40 April/May 2008

31

should insist that HIV-positive people not be subjected to criminalisation or other

coercive measures solely on the basis of their HIV status19. Advocates must demand

that human rights principles of non-discrimination, equality, and due process must

be respected in all lawmaking specific to HIV and AIDS20.

Family planning

Family planning allows individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired

number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through

use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility. A

woman’s ability to space and limit her pregnancies has a direct impact on her health

and well-being as well as on the outcome of each pregnancy.21 All people, including

men and women affected or infected by HIV should have the right to family planning

services.

Overview

Reproductive health services and HIV22

RH services provide an entry point for young sexually active men and women

into the healthcare system. These services provide opportunities for the

provision of a range of HIV prevention, care, and treatment, including

voluntary counseling and testing, condom promotion, management of

sexually transmitted infections, access to male circumcision, and prevention

of mother to child transmission (PMTCT)of HIV.

Condom distribution for HIV prevention can piggyback onto current public

sector condom distribution efforts that primarily target family planning

users.

Family planning is an important and relatively unrecognized tool for

preventing HIV transmission.

In addition, clients receiving HIV services need access to comprehensive and quality

reproductive health services, including family planning.

In many countries RH services are under-funded and inadequate, which undermines

both HIV and RH goals. The role of family planning in HIV prevention needs to be

highlighted. Helping HIV positive women avoid an unwanted pregnancy is one of the

most cost-effective HIV interventions available but it is important that positive

women who would like to have children are supported and followed up with the

19

UNAIDS

International Community of Women Living with HIV and AIDS – why we oppose criminalisation

WHO. (2009). Family Planning. Internet document, available at:

http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/

22 Source: Issues Brief: Global Fund Supports Reproductive Health Commodity Security. (2008). USAID:

Washington. Online document, available at:

http://deliver.jsi.com/dlvr_content/resources/allpubs/logisticsbriefs/GlobFundSuppRHCS.pdf

20

21

32

appropriated services and support that they need in order to ensure the safety of

both the mother and child. Estimates suggest that adding FP services to PMTCT

programs can prevent two times the number of HIV infections and four times the

number of child deaths as Nevirapine treatment. Experts at the World Health

Organization and Johns Hopkins University also advocate that decreasing HIV

transmissions to infants requires not only continued efforts in reducing HIV

infections in women and increasing the reach of PMTCT, but also reducing

unintended pregnancy. Unmet need for contraception is high in Sub-Saharan Africa,

which is the region where HIV infection rates are the highest and where challenges

in implementing comprehensive PMTCT programs are the most significant. Some

experts argue that given the high levels of unmet need for FP and HIV prevalence, as

well as the low levels of knowledge of HIV status by those infected, simply reducing

unmet need for all women would go a long way in reducing HIV transmission.

Improving Reproductive Health

Everyone has the right to enjoy reproductive health, which is a basis for having

healthy children, intimate relationships and happy families. Reproductive health

encompasses the following principles: that every child is wanted, every birth is safe,

every young person is free of HIV, men and boys have RH needs that should be

addressed and every girl and woman is treated with dignity and respect. For women

and girls already living with HIV they also have the right to comprehensive

reproductive health services.

But reproductive health problems remain the leading cause of ill health and death

for women of childbearing age worldwide. Impoverished women, especially those

living in developing countries, suffer disproportionately from unintended

pregnancies, maternal death and disability, sexually transmitted infections including

HIV, gender-based violence and other problems related to their reproductive system

and sexual behaviour. Because young people often face barriers in trying to get the

information or care they need, adolescent reproductive health is another important

focus of reproductive health programming.

Supporting the Constellation of Reproductive Rights

During the 1990s, a series of important United Nations conferences emphasized that

the well-being of individuals, and respect for their human rights, should be central

to all development strategies. Particular emphasis was given to reproductive rights

as a cornerstone of development.

Reproductive rights were clarified and endorsed internationally in the Cairo

Consensus that emerged from the 1994 ICPD. This constellation of rights, embracing

fundamental human rights established by earlier treaties, was reaffirmed at the

Beijing Conference and various international and regional agreements since, as well

as in many national laws. They include the right to decide the number, timing and

33

spacing of children, the right to voluntarily marry and establish a family, and the

right to the highest attainable standard of living, among others.

What Are Reproductive Rights?

Attaining the goals of sustainable, equitable development requires that individuals

are able to exercise control over their sexual and reproductive lives. This includes

the rights to:

Reproductive health as a component of overall health, throughout the life

cycle, for both men and women, both infected and affected by HIV and other

STIs

Reproductive decision-making, including voluntary choice in marriage,

family formation and determination of the number, timing and spacing of

one's children and the right to have access to the information and means

needed to exercise voluntary choice

Equality and equity for men and women, to enable individuals to make free

and informed choices in all spheres of life, free from discrimination based on

gender and or sexuality

Sexual and reproductive security, including freedom from sexual violence

and coercion, and the right to privacy.

Reproductive Rights and International Development Goals

The importance of reproductive rights in terms of meeting international

development goals has increasingly been recognized by the international

community. In the September 2005 World Summit, the goal of universal access to

reproductive health was endorsed at the highest level. Reproductive rights are

recognized as valuable ends in themselves, and essential to the enjoyment of other

fundamental rights. Special emphasis has been given to the reproductive rights of

women and adolescent girls, and to the importance of sex education and

reproductive health programmes.

Reproductive Rights for Women Living with HIV

Many times positive women who go to antenatal clinics face extreme discrimination.

The International Community of Women Living with HIV and AIDS reports that HIV

positive women are often made to stand in separate lines when waiting to see a

health-care provider, are told that they should not be pregnant, are not offered any

confidentiality and in their health folders are branded as HIV-positive for the world

to see.

Women Living with HIV should be able to:

Plan a pregnancy – implicit in this if a woman is not living with HIV she

should have the right to protection at conception.

Talk through with a health-care provider what the best treatment is – this

must be done in a friendly environment

34

Think about how the birth will take place and have options to caesarean

section or natural birth if she so wishes. And following the birth

Discuss the pros and cons of breastfeeding especially with no access to clean

water and given that in many parts of Africa, the entire family looks after the

child and not just the mother.

Life Cycle Approach

Reproductive health is a lifetime concern for both women and men, from infancy to

old age. UNFPA supports programming tailored to the different challenges they face

at different times in life.

In many cultures, the discrimination against girls and women that begins in infancy

can determine the trajectory of their lives. The important issues of education and

appropriate health care arise in childhood and adolescence. These continue to be

issues in the reproductive years, along with family planning, sexually transmitted

infections and reproductive tract infections, adequate nutrition and care in

pregnancy, and the social status of women and concerns about cervical and breast

cancer.

Male attitudes towards gender and sexual relations arise in boyhood, when they are

often set for life. Men need early socialization in concepts of sexual responsibility

and ongoing education and support in order to experience full partnership in

satisfying sexual relationships and family life.

Critical Messages for Different Life Stages

In its advocacy and programming, UNFPA focuses on key messages that can

empower both women and men at different stages of their lives.

Girls and Boys

Inform and empower girls to delay pregnancy until they are physically and

emotionally mature.

Inspire and motivate boys and men to be sexually responsible partners and

value daughters equally as sons.

Encourage governments to take responsibility for the human catastrophe of

orphans and other children who live in the streets.

Adolescents

Reorient health education and services to meet the diverse needs of

adolescents. Integrated reproductive health education and services for young

people should include family planning information, and counselling on

gender relations, STIs and HIV/AIDS, sexual abuse and reproductive health.

Ensure that health care programmes and providers' attitudes allow for

adolescents' access to the services and information they need.

35

Support efforts to eradicate female genital cutting and other harmful

practices, including early or forced marriage, sexual abuse, and trafficking of

adolescents for forced labour, marriage or forced prostitution.

Socialize and motivate boys and young men to show respect and

responsibility in sexual relations.

Ensure that young women living with HIV are not coerced into sterilisation

because of their status.

Adulthood

Improve communication between men and women on issues of sexuality and

reproductive health, and the understanding of their joint responsibilities, so

that they are equal partners in public and private life.

Enable women, especially women living with HIV to exercise their right to

control their own fertility and their right to make decisions concerning

reproduction, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.

Improve the quality and availability of reproductive health services and

barriers to access.

Reorient and strengthen health care services to better meet the needs of men

Skilled attendance at birth.

Make emergency obstetric care available to all women who experience

complications in their pregnancies.

Encourage men's responsibility for sexual and reproductive behaviour and

increase male participation in family planning.

The Older Years

Reorient and strengthen health care services to better meet the needs of

older women.

Support outreach by women's NGOs to help older women in the community

to better understand the importance of girls' education, reproductive rights

and sexual health so that they may become effective transmitters of this

knowledge.

Develop strategies to better meet needs of the elderly for food, water, shelter,

social and legal services and health care.

Information and services on menopause

Family planning23

Family planning allows individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired

number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through

use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility. A

woman’s ability to space and limit her pregnancies has a direct impact on her health

and well-being as well as on the outcome of each pregnancy. This is also true for

women living with HIV.

Source: Family Planning. (2008). WHO: Geneva. Online document, available at:

http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/

23

36

Antenatal care24

Antenatal Care (ANC) means "care before birth", and includes education,

counselling, screening and treatment to monitor and to promote the well-being of

the mother and foetus. The current challenge is to find out which type of care and in