Accepted Version (MS Word 112kB)

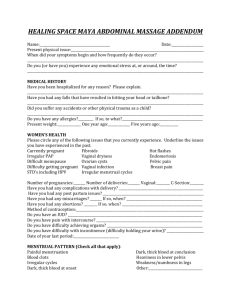

advertisement

Title: Women’s perceptions and beliefs about the use of complementary and alternative medications during menopause Authors: Sara Gollschewski BHSc (Hons)1 Simon Kitto PhD 2 Dr Debra Anderson PhD 1 Dr Philippa Lyons-Wall DipNutrDiet PhD 3 1 Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia 2 School of Rural Public Health, Monash University, Brisbane, Australia 3 School of Public Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Corresponding Author Sara Gollschewski Centre for Health Research Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove Campus Brisbane, Australia 4059 Phone: 61 7 3864 5621 Fax: 61 7 3864 3369 Email: s.gollschewski@qut.edu.au Word Count: 3061 Introduction Within the context of menopause, complementary and alternative medications (CAMs) have the potential to treat acute menopausal symptoms and promote longterm well-being. More than 300 therapies, supplements and activities are currently classified as CAMs(1). The World Health Organisation has defined CAMs as a diverse group of medications, therapies, techniques and exercises which incorporate a range of approaches and philosophies. In addition, the definition recognises CAMs as a multi-treatment approach which aims to ‘prevent illness’ and ‘maintain well-being’ rather than to cure a condition(2). Clinical trials have tested efficacy of specific CAMs in reducing hot flushes however the results are inconclusive(3, 4). Despite a lack of proven efficacy, research suggests menopausal women are using CAMs to treat their symptoms with reported prevalences between 22 and 83%(5-9). In previous work by the current authors, the prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with CAM use were explored among 886 Australian menopausal women(10, 11). CAM use in the sample was high, with 82% using at least one type of CAM. Nutrition was the most commonly cited (67%) individual therapy, followed by phytoestrogens (56%), herbal therapies (41%) and CAM medications (25%) and the characteristics and sociodemographic profile of a CAM user were also identified. Preliminary research has been undertaken with menopausal women to identify reasons that influence CAM use during this transition. A lack of health practitioner support, previous CAM use(12) and personal control over menopause and symptoms(13) were identified in previous research as reasons for using CAMs. In a study with 82 2 American women, CAMs were used to reduce menopausal symptoms and as a preventative measure for long-term health(14). The use of CAMs was seen to embrace the health of the whole body and strengthen the connection between the mind and body. While an understanding of the types, prevalences and factors associated with CAM use is emerging, descriptions and insight into women’s experiences of CAM use during the menopause requires further exploration. This study aimed to contextualise women’s CAM use during menopause by identifying and describing the factors that women self-report as being influential in their decision to use CAMs. Methods Sample Women who are currently using CAMs, aged between 47 and 67 years and fluent in English, volunteered to participate in this study. They were recruited through an advertisement placed in a newsletter distributed by a large Metropolitan hospital, a flyer displayed on noticeboards of Council libraries and shopping centres, and a media release. The method of recruitment, volunteer sampling, ensured that the perceptions and experiences of women who are using CAMs during menopause are explored. This sampling technique does limit the generalisability of the data, however a qualitative research approach was undertaken to explore the factors influencing decisions to seek CAM treatments for their menopausal symptoms and will produce conceptually generalisable findings(15) that will facilitate a deeper understanding of the phenomena. A total of 15 women participated in the study, with 13 in three focus groups and two telephone interviews. Two women who lived in rural Queensland were interested in participating in the study after hearing the media release and consequently, two telephone interviews were undertaken to capture these woman’s experiences. 3 Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Queensland University of Technology Ethics Committee. Data Collection Focus groups were used as the primary source of data collection as they encourage interactions, open discussions and allow participants to react and build on the responses of other members(16, 17) . The questions in both the focus groups and interviews focussed on the following issues: 1) types of symptoms experienced during menopause, 2) therapies other than hormones used to cope with menopause and 3) benefits of using these therapies, and 4) how women learned about these therapies. For this study, women were asked to detail ‘anything you use other than hormone therapy to treat symptoms’. The question was posed this way to avoid preconceptions about the terms complementary and alternative, which would enable women to disclose anything they were currently using for symptom treatment. Focus groups were tape recorded and moderated by the main investigator. Theoretical saturation, where no new or relevant data has been produced, was used to determine the number of focus groups (18). Data analysis Data from the focus group and interviews were transcribed and analysed by thematic analysis utilising open, axial and selective coding(19). Data triangulation, whereby focus groups and semi-structured interviews were used to collect information(20). Researcher triangulation was also employed to collect and analyse the data to capture the complexity of the phenomena studied and enhance the validity of the findings(20) was utilised in this project. An assistant was present to provide supplementary notes 4 on the focus groups and subsequently to aid in the validation of themes and conclusions drawn. With regard to rigorous reflexivity (the impact of the researcher on the data collection and analysis)(17), both the participants and moderator were female which assisted in creating an open and relaxed atmosphere. Results The majority of women were aged less than 55 years, married or defacto and employed (Table 1). Empowerment was the central theme to emerge from the data. This concept of control was embedded within the four themes identified: 1) self management of symptom experiences; 2) menopausal CAM use: types, individual needs and costs; 3) informed choices: the need for validation and control; and 4) health practitioners and their influence on CAM use. The themes that emerged from the data are modelled in Figure 1. Self management of symptom experiences Women expressed a desire to have ownership and control over their menopause experience and treatments used. Self management was intrinsically linked to this control; women wanted to be aware of their body’s individual needs and the menopausal symptoms experienced, and they wanted to have the answer to effectively manage it. Hot flushes, a loss of vitality and tiredness were the most commonly reported symptoms and stress, mood swings, sweating, memory loss, sleep disturbances and tiredness were also reported. The effects of hot flushes generated a lot of discussion within the focus groups and women were eager to share their negative experiences in the work environment, commonly describing a loss of control. 5 “Its embarrassing and overwhelming, especially if you’re the one whose supposed to be talking at the time [in a meeting], they look at you and you can feel the red face coming, it can be quite difficult” (Person 4). The source of symptoms was questioned, with most women believing the symptoms they were experiencing related to ageing and life stresses. Women felt menopausal symptoms, such as hot flushes, were exacerbated by increased external stressors (such as changing in work and family life) during this time. Most women believed a positive mind frame would overcome any symptoms and described menopause as just another phase of life. “I always think for every negative, there’s a positive, so okay I’m going through menopause. Okay that’s fine but…. face it... address it so when you go through it you can still carry on” (Person 2). Menopausal CAM use: types, individual needs and costs The women in the focus groups reported using a number of CAMs including non prescription menopausal supplements, herbs, physical activity, nutrition, massage, oil burning, and aromatherapy and practitioners including a naturopath and Chinese herbalist. By participating in activities such as exercise, healthy eating and taking vitamins women believed they had control over their current symptoms, were improving their health status and ensuring long term health. “We are living a lot longer and therefore we going to have a lot more women who are going to have a lot more years ahead of them and want to live really healthy independent lives” (Person 1). Incorporated in this was women’s desire to be aware of their body’s individual needs and more importantly, finding appropriate treatments and therapies to suit them. 6 “Friends of mine have had the cream and haven’t had the success with it, but everyone is different we all go what’s inside we don’t know and you’ve got to find something to suit the individual” (Person 5). The use of hormones to treat symptoms was evident in the study, with only two women indicating that CAMs were not effectively managing their symptoms. However, both women expressed discomfort taking hormone therapy and were actively seeking an alternative that would suit their needs. The high cost of CAMs used and costs of alternative practitioners were cited as barriers to use. Women expressed concern that the high cost of CAMs was compromising their beliefs and control about their body and the treatments used during menopause. “I spent hundreds of dollars on it [naturopath] and I was a student and not working and I got to the stage where I really cannot afford to keep going”. (Person 6) Informed choices: the need for validation and control A perceived loss of control over their body and symptoms experienced was a common occurrence and information was seen as a positive way to overcome this. Information on alternative therapies was primarily sourced from friends, but also from the internet, magazines, books, work colleagues and general practitioners. Talking to others and sharing information was evident and women were eager to share stories about CAMs and exchanged contact details of supportive general practitioners. “I’ve got a very good solid group of girlfriends and we go to lunch once a month and there’s always someone at a different stage” (Person 4). Women searched for information from multiple sources until they were satisfied with their answers however, reliable information was not easily found, and up to-date, 7 scientific information was considered essential as women equated knowledge to having control over their own choices. “People want a lot of information to, to work out what’s best for them” (Person 7). In a discussion of the recent publication of the Women’s Health Initiative study, which questioned the safety of hormone use(21), most women questioned the outcomes of the research. However, several women felt that it validated their concerns about the use of hormones, and the research supported their use of alternative therapies. “I wasn’t going there anyway, so I wasn’t influenced anyway, but I was like, aha!, I was right about the hormone replacement” (Person 7). Health practitioners and their influence on CAM use Personal experiences with doctors were mostly negative, with women saying ‘you don’t get the option of natural’ or doctors are ‘only interested in hormone therapy’. The relationship between a woman and her health practitioner was perceived to be imbalanced, with many women citing that it was difficult to find a doctor they felt happy and comfortable with. If women perceived their health practitioner was not open to CAMs or accepting of their beliefs, they searched for a practitioner who accepted their decision to use CAMs during the menopause. Women who perceived a negative relationship were less likely to disclose their current use of CAM, and were more likely to self medicate CAMs. Women were adamant about active participation during menopause, in particular, the importance of questioning medical results, reasons for taking a particular medication (hormones), ingredients and the side effects of medication. There was a perceived need for women’s clinics, where women could 8 easily obtain information on menopause and CAMs, but also general practitioners open to alternative therapies. As one women described “…a lot of the doctors are not receptive to the combination of general practitioner work and natural therapy because that’s been their upbringing, that’s been their teaching…I think people in society today are looking for alternatives because we’ve been a little bit sick of going to the doctor and saying here’s your script see you next time and off you go” (Person 2). Discussion A qualitative methodology has enabled an in-depth exploration of women’s perceptions of menopause, and in particular, their experiences of CAM use during this transition. Women were using a variety of CAMs during menopause for two purposes: firstly, to address their current symptoms (in particular hot flushes), and secondly, to promote long term health and wellness. Used in combination, women believed that regular exercise, a balanced lifestyle, healthy eating and the use of vitamins and supplements were an effective way to control over symptoms experienced and protect the body and internal organs. The use of CAMs as both a treatment and prevention is also evident in the literature(14). Threaded throughout the four main themes identified in data was empowerment. Funnel et al (1991, p.#) describes this concept as, “Patients are empowered when they have the knowledge, skills, attitudes and self-awareness necessary to influence their own behaviour…to improve the quality of their lives(22). Empowerment during menopause is not new; in focus groups with 13 women, personal control over health and the treatments used during menopause was a fundamental priority to women(13). 9 Similarly, women’s autonomy during menopause was explored in interviews with general practitioners(23). The concept of empowerment during menopause was illustrated by women in the current study in a number of ways including a desire for ownership of their bodies, self management of symptoms, the use of preventative health methods and access to reliable information and a range of therapies and treatment options (both conventional and CAMs). Central to women’s need for empowerment, was the need to be informed. Murtagh (2003) describes being informed during menopause as not just receiving information, but rather actively seeking and using a variety of information sources to make active decisions about health care during and after menopause(23). Participants in the current study seemed to represent a generation of information seekers, where women actively sourced information on CAMs from a variety of tools; with the internet and friends cited as primary sources. Through access to information, women perceived they were able to gain a better understanding of the changing needs of their bodies, symptoms they were experiencing, and the therapies available to them. The increase in knowledge gained through wider access to a variety of information sources has empowered and enabled women to become more active in their health care decisions(24). Women linked information to personal control over menopause and symptoms experienced, however a lack of scientific validation and information on CAMs was not a deterrent for uptake or continuation of use. Further, women believed that the reduction in the symptoms they experienced outweighed a lack of scientific validation, and if more research was undertaken, positive results for CAMs would become apparent. 10 One of the findings from the focus groups was the majority of women perceived negative relationships with their general practitioners and that this was a factor in their decision to seek treatment outside orthodox medical services as well as not disclosing the full range of therapies they were currently taking. In talking about their experiences with general practitioners, women were describing the asymmetrical power relationship between the patient and medical practitioner. Women wanted to be heard by their doctor, to feel as though their experiences and perceptions were important. Once the decision to use CAMs had been made, women expected their doctor to respect their decision and work collaboratively to meet their needs. Women felt ignored and out of control of the situation when their doctor pressed the use of hormone therapies. The women expressed frustration over the closing down of any opportunity for them to explore CAMs for their menopausal symptoms with their doctor. In previous research, a perceived lack of health practitioner support alongside previous CAM use was identified as reasons for choosing CAMs to manage symptoms during the menopause(12, 13). While most women had an avenue, usually through family or friends, with whom could openly talk with, they still expressed a desire and need to talk about the changes in their lives. The need to be heard and the need to share their experiences is further evidence of this group of women’s desire to gain control over, and feel empowered during their menopause experience. Roberts (2004) suggests that in social situations with friends and family, women are vocal and expressive about their health care, but in the presence of health practitioners become less assertive and more cooperative (24). This was evident to an extent within the focus groups as women openly discussed effective CAMs and swapped contact details of general practitioners open to 11 alternative therapies with other women. When talking to general practitioners some women were vocal and questioning, whereas other women felt pressured into decisions that were not relevant for their body and instead of talking to their practitioner, women sought alternative practitioners. This group of women desired control over their symptoms and the changes occurring during menopause. The need for empowerment during this transition was exemplified by women in the way they perceived their symptoms, the types of CAMs used, the need to find a CAM which suited the individual body’s needs, the need for information and education and the need for supportive health professional’s who respected their decision to use CAMs. While this study has identified and contextualised the factors that influence women to use CAMs, it is important to interpret the findings within the following limitations. Women were recruited through volunteer sampling (which limits generalisability), with the final number of participants lower than anticipated, although seven women in the study were employed full time and women’s busy schedules may have impacted upon the low numbers. Additionally, the sensitivity of the issue may have been underestimated. During the focus groups, women expressed negative feelings towards symptoms and described how menopause was not an openly discussed issue. However, from the women who participated in the focus group, it was evident that there was a need to talk and share experiences of menopause. While low numbers were present, theoretical saturation was reached by the third focus group. The strengths of this study lie in the methodological rigour (both data and research triangulation), and the conceptual generalisability(12) of the key category of empowerment found in this study and its affects on structuring women’s health seeking behaviour in relation to CAMS. 12 There are a number of implications that can be drawn from this research. Firstly, there is a need for information and education about menopause and the range, safety and efficacy of CAMs. Increased education about the processes and biological changes at menopause empowers women with the knowledge of what is happening to their bodies and may help ease some the stresses occurring during menopause. Additionally, there is the need for women’s groups or centres, where women can share their menopause and treatment experiences. Secondly, there is a need for strong participatory relationships between women and their health professionals, particularly general practitioners. Developing such relationships will improve women’s perceived control over their menopause experience, particularly over the types of treatments used to address symptoms. 13 Table 1 Demographics of the focus group and telephone interview sample Variables N Age 55 years and under 10 Over 55 years 5 Marital Status Married/ de facto 8 Separated/ divorced/ widowed 5 Single / Never Married 2 Country of Origin Australia 11 Other 4 Location Urban 13 Rural 2 Education Level Senior school 6 Trade, technical or diploma 5 University or college degree 4 Employment Status Employed full time/ part-time 8 Home duties 3 Student 2 Retired 2 Figure 1 Factors influencing control during menopause Therapy use Suit the bodies individual needs Hormones used Range: supplements, herbs, exercise Self management Prevention Cost of CAMs Informed Choices Knowledge of CAMs Sharing information Education on menopause/CAMs Scientific research on CAMs/ hormone therapy Empowerment during menopause Symptom experiences Individual experiences Affects daily activities Socially debilitating Affecting work capabilities Causes: menopause or ageing? Health Practitioner Support Dr/patient relationship Dr’s perception of CAMs Personal experiences Self medicating Equal relationship desired 15 References 1. Chez RA, Jonas WB. The challenge of complementary and alternative medicine. American journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;177:1156-61. 2. World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy. 2002-2005. Geneva; 2002. 3. Secreto G, Chiechi LM, Amadori A, et al. Soy isoflavones and melatonin for the relief of climacteric symptoms: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study. Maturitas 2004;47:11-20. 4. Knight DC, Howes JB, Eden JA, Howes LG. Effects on menopausal symptoms and acceptability of isoflavone-containing soy powder dietary supplementation. Climacteric 2001;4:13-8. 5. Newton KM, Buist DSM, Keenan NL, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ. Use of alternative therapies for menopause symptoms: results of a population-based sample. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2002;100(1):18-25. 6. Anderson D, Posner N. Relationship between psychosocial factors and health behaviours for women experiencing menopause. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2002;8:265-73. 7. Biddle RA, Wilkinson JM, Simpson MD. Do Australian women use complementary medicines for reproductive conditions? Australian Pharmacist 2003;22(1):52-6. 8. Bair YA, Gold E, Greendale G, et al. Ethnic differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine at midlife: Longitudinal results from SWAN participants. American Journal of Public Health 2002;92:1832-40. 9. Upchurch DM, Chyu MA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among American women. Women's Health Issues 2005;15:5-13. 10. Gollschewski S, Anderson D, Skerman H, Lyons-Wall P. The use of complementary and alternative medications by menopausal women in South East Queensland. Women's Health Issues 2004;14:165-71. 11. Gollschewski S, Anderson D, Skerman H, Lyons-Wall P. Associations between the use of complementary and alternative medications and demographic, health and lifestyle factors in midlife Australian women. Climacteric 2005;8(3):271-8. 12. Will CI, Fowles W. Woman to women: Complementary therapy use in menopause. Journal of Holistic Nursing 2003;21(4):368-82. 13. Seidel MM, Stewart DE. Alternative treatments for menopausal symptoms. Qualitative study of women's experiences. Canadian Family Physician 1998;44:12711276. 14. Richter DL, Corwin SJ, Rheaume CE, McKeown RE. Perceptions of alternative therapies available for women facing hysterectomy or menopause. Journal of Women and Aging 2001;13(4):31-7. 15. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Thousand Oaks; 2004. 16. Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN. Focus groups. Theory and practice. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications; 1990. 17. Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. California: Sage Publications; 1988. 18. Krueger RA. Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research. Second edition. California: SAGE Publications; 1994. 16 19. Ezzy D. Qualitative Analysis. Practice and Innovation. London: Routledge; 2002. 20. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and research design. Choosing among five traditions. United Kingdom: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998. 21. Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. Journal of the American Medical Association 2002;288(3):321-33. 22. Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS. Empowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. The Diabetes Educator 1991;17:37-41. 23. Murtagh MJ, Hepworth J. Menopause as a long-term risk to health: implications of general practitioner accounts of prevention for women's choice and decision-making. Sociology of Health and Illness 2003;25(2):185-207. 24. Roberts SJ. Empowering older women: strategies to enhance thier health and health care. JOGNN 2004;33:664-70. 17