Script-Le Dejeuner video

advertisement

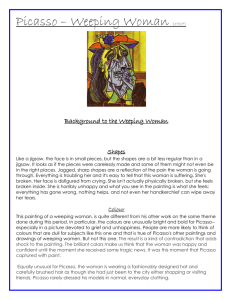

Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 1 Script - Art History Continuum: Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (Bold highlights refer to text added to each slide) Slide 01 - Introduction Welcome to Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, an art history continuum that explores connections between the following painters: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Titian – represents the Venetian Renaissance in Italy Manet – represents a transition from Realism to Impressionism Monet – represents Impressionism Picasso – represents Modernism Yue Minjun – represents Postmodernism These painters are connected to an art history continuum, by their relationship to Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. Slide 01 - Titian’s Pastoral Concert, 1510 We enter this art history continuum by examining a Renaissance painting called The Pastoral Concert, created in 1510, by Titian (perhaps in collaboration with his teacher Giorgione). A wealthy Venetian patron commissioned this painting as an addition to his private collection. In 1671, The Pastoral Concert was sold to a French King, Louis XIV, and is now exhibited in the Louvre, in Paris. It is painted on a large canvas, approx. 41x54”, which was the conventional scale for painting classical history subjects during the Renaissance. The “Pastoral Concert” is painted in the Venetian Renaissance style, with careful attention to atmospheric light and color. In keeping with acceptable Renaissance subject matter, this painting interprets a poem. Two idealized women, symbolically depicted playing the flute and pouring water, illustrate idealized figures from an allegorical Roman poem. These unreal female figures exist only in the imaginations of the two clothed men they inspire, according to the Venetian taste at the time, for simultaneous depictions of the visible and the invisible. The main group of figures is seated in the foreground, at the centre of the landscape. In the background, under a grove of trees, a herdsman tends his sheep. This painted image represents landscape as a state of mind, where humans and nature co-exist in perfect harmony. Three stylistic features identify this Renaissance painting: 1. Invisible brushstrokes 2. Chiaroscuro (gradual transitions between light and dark tones) 3. Linear perspective is used to create the illusion of spatial depth Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 2 Slide 02 - Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863 The second painting in this art history continuum, which this presentation is focused on, is called Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, by Edouard Manet, created in 1863. It signifies a turning point in the history of European art. Manet was a French artist who lived and worked in Paris. He admired, studied, and copied the work of Renaissance Masters when he visited the Louvre. He was particularly inspired by Titian’s painting, The Pastoral Concert. Manet composed Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe on a large-scale canvas (82 x 105”), as a tribute to the Renaissance master. However, Titian’s Renaissance audience was told what the meaning of the Renaissance painting was, in the context of an original poetic story. Titian’s classical Renaissance influence that inspired Manet, was counterbalanced by his subversive interpretation. Manet did not justify his choice of subject (nudes having a picnic with clothed men), by claiming that his painting was an allegory. Manet, in bold defiance of the Renaissance narrative tradition, refused to tell the audience what his painting meant. He wanted to show us that paintings do not have to represent historical events to be significant, or worthy of our attention. Classical allegorical paintings substitute descriptive narrative for aesthetic presence. This focus on story telling prevented paintings from being directly experienced and appreciated for their formal compositional arrangements. These aesthetic considerations include the organization of shapes, values, colors, lines, textures, and spatial relationships. Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe is not a historical allegory that represents an idealized world, but a mysterious tableau of recognizable people. Manet posed his favorite model, his wife, his brother, and his brother-in-law as subjects, against a backdrop of what appears to be a Parisian park. This combination of past and present references, created an unreal scene which viewers were not able to understand, and it shocked the public’s sensibilities. Manet’s style of painting was considered vulgar during the Victorian era when it was painted, because he painted real people, not idealized imaginary figures. Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 3 Apart from Manet’s scandalous choice of live models as his subjects, there are three formal reasons why Manet’s painting does not conform to the traditional classical Renaissance painting style: 1. No chiaroscuro: Manet did not paint subtle gradations between light and dark tones, but instead, leaves abrupt contrasts between tones. Due to this focus on visual tensions between shapes, he was reproached for his “mania for seeing in blocks”. 2. No linear perspective: Manet deliberately avoided using the Renaissance technique of applying linear perspective to create the illusion of spatial depth. The characters in his composition seem to fit uncomfortably into the sketchy wooded background, with no clear vanishing point. 3. Visible brushstrokes: Manet did not blend his brushstrokes to create a finished surface, but allowed the physical process of applying paint to a canvas, show through. At this point, you may be wondering why Manet’s painting became so famous in the history of European art. When Manet submitted Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe to the annual Paris exhibition, called The Salon, it was rejected, along with may other now famous, paintings by artists such as Cezanne and Whistler. The year 1863 is important because the Salon des Refuses, (Salon of the Refused), came into being. The Salon des Refuses was an exhibition held in Paris, by command of the French Emperor Napoleon III, for those artists whose works were rejected by the official Salon jury. Manet’s painting, Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, became the principal attraction during the Salon des Refuses. It generated both laughter and scandal, because it did not conform to the public’s expectation of “good taste”, or to the moral standards that critic’s expected classical art to uphold. Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe changed the history of European art. It is a testimony to Manet’s appreciation for, yet refusal to conform with, historical conventions of narrative painting subjects and modes of representation. This painting could be considered the turning point for Modern Art, because it allowed the Impressionists the freedom they needed to paint common scenes, rather than grand, symbolic stories. Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 4 Slide 03 - Monet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, 1865 In the third slide, we see the Impressionist painter Monet’s interpretation of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, from 1865, two years after his friend Manet, had created such a scandal with the original Le Dejeuner. Monet’s composition did not create sensational news. Monet lacked the conceptual subtleties of Manet’s treatment of the allegorical Pastoral Concert, which confronted the art establishment. Monet ignored the original theme of the Renaissance Pastoral Concert, and paints only what he sees in a Parisian park, using a fresh lively palette that does resemble Titian’s colors. This painting reveals Monet’s talent for observing the play between color and light, which is a defining feature of the Impressionist aesthetic, and why Monet stands out as a leader of the Impressionist movement. Slide 04 - Picasso’s interpretations of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, 1960-62 The fourth slide leads us to one of Picasso’s interpretations of Le Dejeuner, inspired by Manet’s original painting. In 1932, Picasso saw Manet’s famous painting exhibited in Paris. He was so impressed, he wrote this message on the back of the gallery envelope: “When I see Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, I tell myself there is pain ahead.” Picasso studied many European masters, including Poussin, Velazques, and Rembrandt. But his attempts to come to terms with Manet’s painting, was the most remarkable tribute that one painter has ever paid another. From 1959, until the end of his career, Picasso completed a series of 27 paintings, 140 drawings, and sculptures based on the figures posed in Manet’s painting. This was the most profound and complex exploration of any subject that Picasso ever undertook. Picasso admired Manet’s modernity and subversive attitude. Even though Picasso predicted his involvement with Manet’s painting in 1932, he waited 24 years before he began to seriously confrontation it with his own variations. In 1954, Picasso opened a sketchbook, and wrote on the cover First Drawings of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, 1954. At that time, he completed four drawings based on Manet’s painting. He studied its layout, its protagonists, and the formal relationships between these elements. Picasso, like Manet before him, copied and interpreted at the same time. He modified the original composition, like Manet had done with the Renaissance work that inspired him. Today, in our postmodern world, we refer to this practice of borrowing another person’s work without their permission, as appropriation. From 1954 to 1959, Picasso explored many variations of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 5 Manet’s composition in drawings. There was no pain involved in any of these experiments, only amusement, and typically, for Picasso – showmanship. Picasso took his time reducing his anguish towards Manet’s painting. In 1960, he produced his first painted version of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. Slide 05 - Picasso’s interpretations of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe In this slide, we see another variation by Picasso, appropriating, or borrowing the composition from Manet’s original painting, Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. Picasso rearranged the players in the scene, reorganizing the formal elements into a new composition. The characters change roles and positions in the play, receding, or coming forward, establishing a new scene each time. Like Manet, Picasso was not following representational conventions, but was making a statement in favor of artistic freedom. Slide 06 - Picasso’s interpretations of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe In 1962, Picasso designed a set of sculptural models based the characters from Le Dejeuner. These large, cardboard figures, were folded and placed in real landscape settings, for Picasso to photograph and create new arrangements to experiment with. Later, a sculptor was hired to create concrete versions of these models, which are permanently located in a real park. He transformed the original composition into many new arrangements of the figures. In 1970, when Picasso was 89 years old, he painted his final interpretation of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe. Picasso transcended his connection to Manet’s painting, by referring to the whole history of painting, and establishing himself as a significant part of the art history continuum. Manet was the first painter to break with tradition, while at the same time referring back to the Renaissance masters. Picasso, a leader in the Modern Art movement, recognized that he was participating in a dialogue about painting. Perhaps it was at this intersection, where the painter challenges the past that the source of Picasso’s anguish resided. Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe: an art history continuum, by Deanna Georgeson. 6 Slide 07 – Yue Minjun’s Le Dejeuner 1995 In the final slide, we see the work of a contemporary, Postmodern Chinese artist, Yue Minjun, once again, practicing the art of appropriation. He creates self-portraits by photographing himself in a variety of poses, as reference material for paintings and sculptures. Every image Minjun creates includes his enigmatic, exaggerated smile. Like Manet and Picasso before him, he never tells us what this smile means. The repeated smiling portrait of Yue Minjun, is a postmodern phenomenon, which has been defined by Modernism. Postmodernists combine respect and ridicule towards Modernism, as a failed attempt to represent an unachievable utopia. When we look at Minjun’s Le Dejeuner, we might ask ourselves why every character wears the same smile? Does Minjun respect European art history, or is he ridiculing it? We are never certain of the artist’s intentions. Perhaps they represent artificial smiles that can be purchased and applied like make-up. Can these smiles be manufactured in large quantities, like mass-produced and consumed products? These questions are open to interpretation. However, unlike the allegorical Renaissance paintings, we have no artistic authority telling us what to think. We must reach our own conclusions.