PIHMunich

advertisement

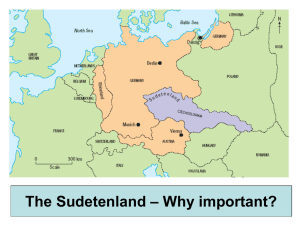

1 1.) Munich Crisis (Reached Its height in the Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938) 2.) Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) 3.) The Sudetenland 4.) Czechoslovakia (capital city: Prague; divided into Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1992) 5.) Appeasement (to appease: “to pacify or to conciliate”; or: “to buy off an aggressor through concesions”) 6.) Woodrow Wilsons’s “Fourteen Points” (Issued during WWI) 7.) National Self-Determination; Nation-State 8.) Three Varieties of Ethnic Cleansing 9.) Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain of Great Britain (1869-1940) 10.) Prime Minister Eduard Daladier of France (1884-1970) 11.) President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia (1884-1948) 12.) Multi-Party Rule (Democracy) vs. Single-Party Rule (Totalitarianism) 13.) Thomas G. Masaryk (1848-1937) 14.) Prague University (Divided into Czech and German Halves in 1882) 15.) Multinational State (Czechs 46%; Slovaks 40%; Germans 10%; also Ruthenes and Hungarians) 16.) Pětka (Coalition of Five Parites Listed in Term #17) 17.) Czech Agrarian Party, Czech National Democratic Party, Czech Social Democratic Party, Czech National Socialist Party, Czech Populist Party 18.) Slovak Agrarian Party, German Agrarian Party, and German Social Democratic Party 19.) Great Depression (began October 1929) 20.) Sudeten-German National Front (est. 1934; grew from pro-Nazi activities in Sudetenland) 21.) Konrad Henlein (1898-1945) 22.) Sudeten-German Party (new name for Sudeten-German National Front starting 1936) 23.) Drang nach Osten (Push to the East) 24.) rearmament, universal military conscription, and occupation of the Rheinland 25.) Anschluss (annexation of Austria in Germany; March 12, 1938) 26.) Czechoslovak-French Military Defense Pact (1924) 27.) Czechoslovak-Soviet Military Defense Pact (1935) 28.) Hitler-Henlein Meeting, March 1938: “always demand so much that we will never be satisfied.” 29.) Karlsbad Demands (April 24, 1938) 30.) Runciman Mission (August, 1938: Walter Runciman of Great Britain) 31.) Three Meetings Comprising Munich Crisis of September 1938: Berchtesgaden (September 15, 1938); Bad Godesberg (22 September, 1938); Munich (30 September, 1938) 32.) Munich Agreement (signed just after midnight September 30, 1938) 33.) Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (Leader in 1938 until 1953: Klement Gottwald) 34.) Nazi Occupation of Czechoslovakia (March 15, 1939) 35.) Czechoslovakia Divided into Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; and Slovakia 36.) Reinhard Heydrich (1904-June, 1942; assassinated by Czech resistance) 37.) Final Solution (Nazi Holocaust) 38.) Old-New Synagogue in Prague and Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague 39.) Museum of an Extinct and Vanished People 40.) Terezin [Terezienstadt] 41.) Lidice (destroyed June 1942 as punishment/warning for Heydrich’s assassination) 42.) Expulsions (approximately 3-million Germans forced to leave Czechoslovakia after WWII) 2 I. Introduction to the Munich Crisis: The Troubled History of the Nation-State Slide 1 --The Munich Crisis was a momentous event that reached its height on September 30, 1938. --It had a grave impact on the history of World War II and on some wars since then. -- The primary catalyst for the Munich Crisis was Adolf Hitler’s demand that the Sudetenland be given to Nazi Germany. --The Sudetenland was a region in northern and western Czechoslovakia. --We will learn more details about Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland in a few minutes. Slide 2 --Hitler made his demand for the Sudetenland based on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s “14 Points.” --Among other things, the “14 Points” called for the right of national self-determination. --This meant that ethnic groups were to be able to choose what state they belonged to. --In Central Europe, where nationalism was strong, most ethnic groups wanted to belong to nation-states. --A nation-state is a state that is composed of one national group only, rather than being multinational in composition. --The nation-state concept emerged from the many nationality conflicts that had plagued Central Europe during the 19th century and that many people thought was a major cause of World War I. --World War I devasated Europe physically and emotionally. --There was a tremendous death toll, and people were left horrified of future war. --Germany was accused of starting WWI, and was made to pay heavily for this charge. --During the interwar period the nation-state was held up as a just, moral, and a democratic principle. --It is an idea that came to have a long and ambiguous history well into our own times. --It is an idea that has led to national liberation for some groups, and ethnic cleansing for others. Slide 3 --There are three varieties of ethnic cleansing, to which the idea of the nation-state has contributed. --We see all three of these varieties occurring when we look at the Munich Crisis; --The varieties are: --1.) taking away a country’s territory and giving it to someone else based on the national or ethnic composition of that territory (this happened in the Munich Agreement); 3 --2.) intentionally killing members of a national or ethnic group who are considered different from other members of the state (this happened in the Nazi Holocaust, which the Munich Crisis helped make possible); --3.) expelling or kicking out members of a national or ethnic group who are considered different from other members of the state (this happened with the post-war expulsions, when Czechs sought retribution or payback for Nazi brutality). --It is striking to note that Adolf Hitler used Woodrow Wilson’s “14 Points” as the justification for his demands. --This totalitarian leader rested his claims for a piece of Czechoslovak territory on a principle that was viewed as just, moral and democratic. --Perhaps the idea of the nation-state was just, moral and democratic, although Hitler certainly did not use that idea for just, moral or democratic ends. -- Hitler's demand for the annexation of the Sudetenland caused a Europe-wide crisis to which a number of European leaders responded. --Let’s thus briefly meet some of these leaders. Slide 4 --The main western European leader who became involved in the Munich Crisis was Neville Chamberlain. --Chamberlain was Prime Minister of Great Britian at the time of the Munich Crisis. --Chamberlain received support from Eduard Daladier. --Daladier was Prime Minister of France at the time of Munich. --The Czechoslovak leader during the Munich Crisis was President Eduard Benes. --All three leaders were heads of democratic countries. --They did not all have universal adult suffrage, but they did all have multiparty rule. --Chamberlain of Great Britian and Daladier of France shared something in common that greatly influenced their approach to Hitler’s demands. -- The English and French leaders believed that if war broke out between Germany and Czechoslovakia that another major European war would result. --Memories of the death, suffering, and trauma of World War I were still strong in France and Great Britain. --They especially feared another war, because their countries were not strongly militarily prepared for war; being militarily prepared for war meant spending a lot of money, in a time of economic shortage. -- Thus, the thought of another war similar to World War I made the British and French leaders fear another European war. --They also feared something else. --They feared that their publics would not support another war. 4 -- Stated differently, they feared that if war broke out during their term, then they would be voted out of office. -- Chamberlain especially had this fear. --Benes did not want another world war, but he had an even greater fear during the Munich Crisis. --Benes’s greatest fear was being diplomatically isolated from Britain and France, if he did not go along with Britain and France. --He feared that without British and French support any war with Germany would be absolutely, completely, 100% devastating for the Czechs of Czechoslovakia. Slide 5 --The location of Czechoslovakia in the middle of Europe, far from France and Britain, fed Benes’s fear; so did a powerful Czech-German national rivalry that began in the 19th century. --Of the three democratic leaders, it was Neville Chamberlain who had the most influence when trying to respond to Hitler’s demands for the Sudetenland. -- Chamberlain’s approach was to try to appease Hitler. Slide 6 --The general, non-historically loaded meaning of appease is “to pacify or to conciliate.” --Since the Munich Crisis it has also come to mean “to buy off an aggressor through concessions, in order to maintain peace and with a sacrifice of principles;”it is now also associated with weakness. --Some argue that in this way the Munich Crisis contributed to American involvement in wars in Vietnam and more recently in Iraq. -- The Munich Crisis was a very interesting and a very troubling moment in the history of 20th-century European and world history. --To understand its history, it is best to know about the places and people involved. --I’m going to assume that you already have some background knowledge about Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party. --The history of Czechoslovakia and the Sudetenland are far less known, so I will spend some time introducing you to their histories and their leaders. II. Czechoslovakia: New Statehood, Multiparty Rule, and Minority Rights Slide 7 -- Czechoslovakia was born in November of 1918. -- It was one of a number of states that came into being right after the end of WWI and its creation was based on Woodrow Wilson’s “14 Points.” --Its capital was Prague, the capital of the once independent Kingdom of Bohemia. 5 --It was carved out of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, a large empire between Germany and Russia that had been home to a great number of different national groups and a lot of nationality conflict. -- The new Czechoslovakia, which was formally known as the First Czechoslovak Republic, had a democratic parliament with multiparty rule and universal adult suffrage. -- Its first president was the much beloved Tomas G. Masaryk. -- Before WWI Masaryk was a professor of philosophy and sociology at the Czech half of the Prague University. -- The Prague University had been divided into a Czech half and a German half in 1882. -- This division of the university along national lines was a result of an intense rivalry between Czechs and Germans during the 19th century (a rivalry that continued into the 20th century). -- Masaryk remained president of Czechoslovakia until 1935, when he retired. -- He died two years later in 1937 at the age of 87. -- During his long presidency, Masaryk's #1 assistant was Edvard Benes. -- Benes lives from 1884 to 1948. -- Benes was foreign minister of Czechoslovakia until 1935. --As foreign minister, Benes had a lot of experience with diplomacy and foreign affairs. -- Then in 1935 he became president of the county. -- He was President of Czechoslovakia during the Munich Crisis, when his foreignaffairs experience was strongly put to the test (it is debated whether Benes did a good job or not during the Crisis). Slide 9 -- Czechoslovakia was not a true "nation-state" like Woodrow Wilson called for in his "14 Points." -- Czechoslovakia contained a plurality of national groups and ethnic groups. -- Czechs were the group that had the most power over the federal government. -- And yet they made up only 46% the total population of Czechoslovakia. -- The other main national group was the Slovaks. -- They made up about 40% of the total population. -- Czechs were concentrated in the western half of Czechoslovakia. -- Slovaks lived in the eastern half. -- In addition to the Czechs and Slovaks, there was a notable German minority in the new Czechoslovakia. -- The German minority made up about 10% of the total population of the new "nationstate." -- A very small German community lived in Prague, which was mostly a Czech city. 6 -- Most of the German minority lived in an area of the country called the Sudetenland. --The Sudetenland was located in a swath of territory stretching around the northern and western edges of Czechoslovakia. --We’ll learn more a it in a bit. --Two smaller ethnic groups within the “nation-state” of Czechoslovakia were the Ruthenes and the Hungarians. -- It is important to note that while the Czechs had only 46% of the population, they dominated the government of the country. -- How'd they do that? -- The high number of political parties in the national parliament made this possible. Slide 10 -- The Czechs alone had several political parties. -- The Germans and the Slovaks each had several as well. -- But unlike the Germans and the Slovaks, the Czechs managed to get the leaders of their five parties to form a coalition. -- This coalition is known as the Petka. -- Petka means group of five. -- This coalition of Czech parties always met together before parliamentary sessions. --Parliament met in former concert hall and art gallery. -- In those meetings, they would decide together how, as a block, they would vote for law proposals. -- This meant they could often get the majorities needed to get laws passed in the first place, and to get laws passed in favor of Czech interests. --The names of the parties in the Petka were: Czech Agrarian Party, Czech National Democratic Party, Czech Social Democratic Party, Czech National Socialist Party, Czech Populist Party. -- By 1925 the Petka dominated the political life of Czechoslovakia. -- By that time, though, it was also an object of criticism. -- Slovaks and Germans attacked it for making the government of Czechoslovakia a tool by which the Czechs were oppressing other national groups in the country. -- The Czechs in the Petka responded to this criticism by opening their coalition government up to other parties. -- In 1925 the Petka expanded to include the Slovak Agrarian Party. -- In 1926 it expanded to include the German Agrarian Party. -- In 1929, just before the Great Depression, it expanded to include the German Social Democratic Party. 7 -- Thus, in 1929 – before the Great Depression -- the government was a successful democratic country with multiparty rule that was allowing ethnic minorities a say in government. -- The government was becoming democratic and making some non-Czechs happy. --And then came the Great Depression starting in October of 1929. III. The Sudetenland: Economic Hardship and the Mobilization of German Discontent --We’ll return to the Great Depression in a minute, but first it behooves us to look at the Sudetenland – that part of Czechoslovakia that was causing so many tensions in Europe in 1938. Slide 11 -- The Sudetenland formed the western and northern rim of Czechoslovakia. -- Shared a border with Germany. --It covered roughly one-fifth of Czechoslovakia’s territory and contained one-quarter of its population. --That population included a total of roughly 3.5 million people, 700,000 of whom were Czech and rest German. --This is the bulk of the German population of Czechoslovakia; very few Germans lived in other parts of Czechoslovakia. Slide 12 -- The Sudetenland was a highly industrialized area. --In total, the area contained 70% of Czechoslovakia’s iron and steel works, and 70% of its electrical works. -- It contained most mines of Czechoslovakia and most chemical works (great chemical works). -- And it contained most munitions works of Czechslovakia (great munitions works). Slide 13 --The Sudetenland was a very mountainous area. -- And as a mountainous area it formed a natural defense barrier between Czechoslovakia and Germany. --And it contained important military defenses for the country, including a line of steel bastions not unlike France’s Maginot Line. --Taken together – the mountains and the military defenses – made the Sudetenland an important protective shield around the heart of Czechoslovakia (take away that shield and…). -- The Great Depression hit Czechoslovakia hard just as it hit other parts of the world hard. 8 -- Slovak farmers in the eastern half of the country suffered, because prices for their agricultural goods dropped. -- Many Slovaks blamed the Czechs and Jews for their problems. --This led to the rise of a right-wing anti-Czech and anti-Semitic movement in Slovakia. -- Germans in the Sudetenland really suffered economic hardship due to the Great Depression. -- These Germans earned their livings working in industry. -- No one was buying industrial goods during the Great Depression. -- This meant the factories in which they worked first slowed down production and then closed. -- Unemployment soared in the Sudetenland. -- German workers couldn't simply work their farms for food like Slovak farmers could. -- The Sudeten Germans were extremely economically distressed. -- And they blamed Czechs and also Jews for their troubles. -- You no doubt know already that Nazism began to spread in Germany during the 1920s and it grew very strong in the 1930s by appealing to the economic sufferings of average Germans during the Great Depression. -- During the early 1930s Nazism began to spread to the Sudetenland. -- Nazis operating in the Sudetenland appealed to the economic hardships of the Germans there. -- They placed blame for the economic hardships on the Czechs controlling the national government of Czechoslovakia. -- Sudeten-German Nazis were exploiting economic discontents just like Nazis in Germany were doing. --These appeals were highly successful. -- The Nazi challenge grew so strong that in 1931 the Czechoslovak government felt it necessary to take steps to stop the further spread of Nazi popularity. -- In that year it banned the Nazi Party from Czechoslovakia; and it banned the wearing of Nazi uniforms. -- This didn't stop Nazi activities, however. -- In 1932 the Czechoslovak government arrested, tried, and jailed leaders of the Nazi youth movement in the Sudetenland. -- The leaders of this youth movement were plotting an armed rebellion. -- The arrests also didn't stop Nazi activities either. -- What the government efforts did was drive the Nazi movement underground. -- It re-emerged in 1934 as a new political party called Sudeten-German National Front. 9 Slide 14 -- The leader of the Sudeten-German National Front was a Sudeten-German nationalist named Konrad Henlein. -- Henlein and his followers maintained they were not Nazis. -- They also claimed that they did not desire harming Czechoslovakia in any way. -- They said they only wanted one thing. -- They said they only wanted Germans to have complete control over local affairs in areas with large German populations, so that Germans would be treated fairly. -- By local affairs, they wanted control over education, the court system, and the police. -- The Czechoslovak government resisted satisfying Henlein's demands. -- Czechoslovak leaders found them dangerous, because the government knew of too many ties between Henlein and the Nazis. --Indeed, Henlein and the Nazis had a lot of ties. --In fact, in 1934 Hitler began funding the Sudeten-German National Front. --The Front was receiving more campaign contributions from Hitler than any other party in Czechoslovakia received from any other source. --The funding brought results. --In the 1935 national elections the Sudeten-German Party received more than 60 percent of the German vote (the last national elections before WWII). --In local elections held in May 1938 that party received 78 percent of all German votes. -- Still, to escape further arrests of party members, Henlein tried again to dissociate himself and his party from the Nazis. -- In the Summer of 1936 he reorganized the Sudeten-German National Front. -- He gave his party a new name. -- He called it the Sudeten-German Party. -- He hoped this new name wouldn't sound so threatening to the government. -- Henlein's new party continued to call for German control over local affairs in areas with large German populations. -- They also called for the separation of the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia and its annexation to Nazi Germany. -- Sudeten Germans said that they wanted to live in a German state. -- They said that this was in keeping with Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points and the idea of a “nation-state.” -- Hitler had the goal of expanding Nazi German territory into eastern Europe. -- This was part of his Drang nach Osten – or “Push to the East” policy. --By Summer of 1938 Hitler had been preparing for his push to the East for three years. --In 1935 he ended all restrictions on rearmament and introduced universal military training. --In 1936 he occupied the Rhineland; Hitler expressed surprise that no one stopped him. 10 --Why didn’t the western democracies stop Hitler at either of those times? --Would the Munich Crisis have happened if they had; would Nazi domination of Europe during WWII have happened if they had? --Were the western democracies so afraid of war, or was there another reason that they didn’t stop Hitler? IV. The Munich Agreement: Crisis of Democracy? -- Hitler carefully watched and manipulated the activities of the Henlein and the Sudeten Germans. -- He saw the Sudeten-German Nazi movement as providing him with an opportunity to expand Nazi Germany to the east. -- It was in February of 1938 when Hitler first vociferously called for the separation of the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia and its annexation to Nazi Germany. -- In a February 1938 speech Hitler said that this annexation needed to be done in the name of national self-determination and was in keeping with Wilson's 14 Points. --He stated that he would protect “those fellow Germans who live beyond our frontiers and are unable to insure for themselves the right to a general freedom, personal, political, and ideological.” --This was a demand that did not cause much alarm among other European powers until the following month. Slide 15 --On March 11 and 12 radio and newspaper reports broadcast very concerning news to the world. --They announced that on March 11 Germany invaded Austria and took over the government in Vienna; and on March 12 Hitler declared the Anschluss. --The Anschluss was the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany after Nazi troops took over the government in Vienna. --Czechoslovakia was now ringed on three sides by Nazi Germany. --Now instead of having 700 miles of border exposed to Hitler, the country has 950 miles of border exposed to him. --This was very alarming to Czechoslovaks. --This Nazi takeover of Austria was also greatly alarming to other Europeans. --In response to the Anschluss and fearing the outbreak of war as a result of it, Great Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain reexamined his foreign policy in Central Europe. --In a speech in parliament Chamberlain declared that Great Britain did not see itself bound to defend Czechoslovakia from Nazi aggression. 11 --He added, though, that if France found itself involved in a war to defend Czechoslovakia, then Britain would join in the conflict on the side of France. --While the first part of this speech was not good news for Czechoslovakia, the second part was. --This is because France and Czechoslovakia had a 1924 defense treaty stating that France would fight to defend Czechoslovakia in case of war. --Czechoslovakia felt reassured by this treaty, although in the end France chose to break its terms. --Czechoslovakia also had a 1935 defense pact with the Soviet Union. --The Soviet Union said it would come to the military defense of Czechoslovakia, but only if the French did. --Czechoslovakia pinned great hopes on French assistance due to these two treaties, but these hopes were painfully disappointed. --Anxieties about the possibility of war breaking out due to Nazi aggression reached new heights on April 24, 1938. --In that month Nazi troop movements at the border of Czechoslovakia were reported, although no military action took place. --In the same month Konrad Henlein, leader of the Sudeten German Party, made new demands on the Czechoslovak government. Slide 16 --These demands are called the Carlsbad Demands, because they were announced in the Czechoslovak city of Carlsbad. -- Karlsbad is a spa-town in western Czechoslovakia that had a strong German majority. --There were 8 Karlsbad demands, and on the whole this was a rather murky list of demands. --The clearest was demand #4 which demanded Sudeten self-government in all areas of public life. --That would include in the schools, the courts, and the police. -- Demand #8 called for the freedom to follow the Nazi Party and its values. --During the Summer of 1938 Great Britain put pressure on Czechoslovakia to meet Henlein’s demands, as a means of avoiding war. --The Runciman Mission resulted due to this pressure (Runciman was Brit. diplomat). --In this mission, Walter Runciman was sent by Chamberlain to Czechoslovakia, in order to tell Benes that he had to accept the Carlsbad Demands. --Runciman was very pro-Sudeten-German. Slide 17 12 --Great Britain did not know that Henlein had been instructed by Hitler to keep asking for more. --Hitler told Henlein in March 1938 “always demand so much that we will never be satisfied.” --The Carlsbad Demands were very difficult demands to accept, because they prepared the way for the Sudetenland leaving Czechoslovakia. --Under pressure from Great Britain, President Benes tried to meet Henlein’s demands. --Still, due to Henlein’s agreement with Hitler, whatever Benes proposed was never enough for the Sudeten-German leader. --On September 7, 1938 Henlein learned that Benes was willing to grant all the demands that Henlein had made in the Carlsbad Demands. --This generous offer put Henlein in a rough position: if he accepted, then there would be no more reason to criticize and attack the Czechs, or to demand that the Sudetenland become part of Germany --To avoid having to accept Benes’s offer, Henlein and his followers staged a violent incident on the very day that the offer was made. --When Czechoslovak police arrested Sudeten-Germans in the incident, Henlein called off negotiations with Benes. --Violence spread further in the Sudetenland. --Hitler denounced the violence as evidence of how Czechs were abusing Germans. --The violence frightened Chamberlain who decided to call a meeting with Hitler to try to find a solution to the Sudeten problem. Slide 18 --This meeting was the first of three meetings in September of 1938, all three of which belong to the Munich Crisis (and only one of which took place in Munich). --The meeting took place on September 15 in Berchtesgaden. --At the meeting, Hitler demanded that all territories in the Sudetenland in which the majority of people were Germans should be given to Germany. --Chamberlain said he would ask the British and French governments to consider his demand. --He proposed that areas with more than 50 percent Germans be given to Germany. --Then the new borders of Czechoslovakia would be determined. --This was a proposal that would leave Czechoslovakia resembling Swiss Cheese. --The British and French governments accepted the proposal. --Czechoslovakia rejected it. --France stated that if Czechoslovakia did not accept the proposal, then France would not stand by their treaty promising military defense to Czechoslovakia. 13 --This was horrifying to Benes, who feared military isolation for his small country in the middle of Central Europe. --Chamberlain met again with Hitler on September 22, this time is Bad Godesberg. --There he informed Hitler that Great Britain and France had agreed to Hitler’s demand. --He thought that Hitler would be delighted with the British and French agreement. --Hitler, however, now wanted more. --He wanted a complete German occupation of the Sudetenland and he wanted all Czechs out of Sudeten territory; plus, he wanted it all done by October 1. --The Czechoslovak Army mobilized upon hearing these demands. --The threat of war was palpable throughout Europe, horrifying Chamberlain. --Chamberlain again met with Hitler, this time on September 29 in Munich. --They were joined by Eduard Daladier of France and Benito Mussolini of Italy. --Benes did not attend. --Just after midnight on September 30 an agreement was reached. --This was the Munich Agreement. --According to it, the Sudetenland had to be given to Nazi Germany and all Czechs had to be out of the Sudetenland by October 10. --Further, all military installations in the area had to be left untouched. --On September 30 Czechoslovak leaders met in Prague to discuss whether to quietly accept the Munich Agreement or to fight to defend Czechoslovak integrity. --Military leaders were prepared to go to war, even though they knew that France would not fight with them. --At that time, Czechoslovakia did have a strong and well-equipped army and had been preparing for the possibility of war with Germany. --In 1937 Czechoslovakia spent 38% of its national budget on defense. --Part of that money was spent on the erection of border fortifications. --Still, they were scheduled for completion in 1942 and were only along the border with Germany, not along the border of Austria which Hitler had added to Germany in the March 1938 Anschluss (from 700 miles to 950 miles of border to defend). --Thus, the fortifications posed one challenge to the Czechoslovak military in the face of Hitler. --Another challenge came from the multinational composition of Czechoslovakia and its army. --If full mobilization was implemented, very fifth soldier and every tenth officer would be a German. --On the other hand, though, Nazi Germany was also not fully prepared for war. 14 --In fact, some leading German generals warned Hitler of defeat if Germany’s troops went up against Czechoslovakia. --So military leaders and many members of the cabinet resisted the terms of the Munich Agreement and vehemently called for war with Germany rather than surrender of the Sudetenland. --The general public supported this view. Slide 19 --One political party strongly called for war against Nazi Germany rather than surrender. --This was the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, then led by Klement Gottwald. --Gottwald lamented that, “Barefoot Ethiopians, without arms, defended themselves, and we yield.” --After World War II, the Communist Party was the most popular party in Czechoslovakia. --This was largely due to the Communist’s opposition to the Munich Agreement. --In 1948 the Communist Party tookover the government of Czechoslovakia and Gottwald became the country’s leader. --The decision to give the Sudetenland to Hitler helped to make this possible. --Despite so much willingness to fight Hitler, the opinion of Benes prevailed. --Benes feared destroying Czechoslovak ties with Britain and France, so he agreed to the Munich Agreement. --He feared slaughter and felt that an all-European war was inevitable, so why not wait until the British and the French had no choice but to fight and help save the Czechs from total annihilation by Hitler (very controversial decision even today). --In his mind, he bought a little time by trading off some space. --On October 5, 1938 Benes resigned from the Presidency and at the end of the month he moved to London, where he later set up the Czechoslovak-government-in-exile. --His private writings indicate that for the rest of his life he agonized over whether he had made the right decision at Munich. Slides 20-22 --On October 10, 1938 most Czechs were gone from the Sudetenland and it was annexed to Nazi Germany. --Germany and Czechoslovakia were both closer to being “true” nation-states, but at what cost? VI. Events after Munich: Nazi Occupation, World War II, Genocide, and Expulsion -- The decision in Munich in September of 1938 did not appease Hitler. 15 -- It just whetted his appetite for more territory in eastern Europe. -- And it fed his confidence that no one would stop him. --What might have happened if Hitler had not been given the Sudetenland? Slide 23 -- In March 1939 Hitler's troops marched into Prague and took over the entire state. -- This marked the end of parliamentary democratic government in Czechoslovakia until after World War II. -- The Nazis divided Czechoslovakia into two separate states. -- The Slovak half was called Slovakia. -- In it right-wing, anti-Semitic Slovaks ran the government with Nazi advisors. Slide 24 -- The Czech half of Czechoslovakia was called the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. -- It was entirely under Nazi control. -- One Nazi was put in charge of the Protectorate was Reinhard Heydrich. Slide 25 -- Heydrich, along with Himmler, was the chief architect of the Final Solution. -- He became head of the protectorate in September of 1941, but was only there about half a year. -- His rule in the Protectorate was brutal! -- Thousands of non-Jewish Czechs were executed under his orders. -- Most were Czech intellectuals. --Heydrich and other Nazis saw intellectuals as the natural leaders of a country, and aimed to kill them to order to wipe out that natural leadership. -- Also, under Heydrich Jewish persecution in the Protectorate was fierce. -- Jews were sent off to a concentration camp called Teresienstadt/Terezin. -- This was an old fortress town built in the days of Empress Maria Theresa. -- Terezin (or Teresienstadt) was not an extermination camp. -- It was a concentration camp. -- None the less, thousands of Jews died there. --Thousands who survived there, were then sent to extermination camps. Slides 26 -- While the Nazis destroyed 100s of 1000s of Jews in the Protectorate, they did not destroy some important sacred Jewish sites. -- The Nazis saved the Old-New Synagogue of Prague and the Old Jewish Cemetery of Prague. 16 -- This was unusual, because everywhere else in Europe the Nazis were destroying synagogues and Jewish cemeteries. -- Why did the Nazis save the Old-New Synagogue of Prague and the Old Jewish Cemetery of Prague? -- It was because they decided to use these buildings for a museum they were planning. -- This was to be a Museum to an Extinct and Vanished People. -- The Museum never came into being, because the Nazis lost. -- At present this synagogue is the oldest synagogue in all of Europe, because it was one of the very few synagogues that the Nazis did not destroy. -- So back to Heydrich. -- I mentioned he was only in charge of the Protectorate for one half year. -- Why only in power only half a year? -- In May of 1942 Heydrich was ambushed in Prague and assassinated. -- Hitler was incensed that someone would assassinate one of his henchmen. -- He was going to show the Czechs that they never wanted to do that again. -- In retaliation for the assassination of Heydrich, Hitler undertook two policies. -- First he selected 1300 individuals to be summarily executed. -- Some were selected randomly; others were selected because they were intellectuals. -- Secondly, Hitler randomly selected a Czech village to be destroyed. -- The unfortunate village that was selected was the village of Lidice. Slide 27 -- The Nazis entered the village of Lidice. -- They shot all the men, and then burnt the village to the ground. The women were sent to an extermination camp; some of the children were selected to be “Germanized” and the rest were sent to an extermination camp. -- Lidice was an example of what would happen to those who tried to resist Nazi rule. --Memories of Lidice and other Nazi atrocities remained strong among many Czechs after May 1945 when Nazis had been defeated and Czechoslovak independence was restored. --Immediately after the war’s end Czechs began to call for retribution or payback for that damage and death that Nazi Germany caused Czechoslovakia. Slide 28 --The desire for retribution led to the expulsion of 3-million Germans from Czechoslovakia in 1945 and 1946. --Benes was the chief promoter of the expulsions. --This was another act of ethnic cleansing taking place in Czechoslovkia in less than a decade. --This latter act of ethnic cleansing left very few Germans in the country after WWII. --Czechoslovakia was one step closer to being a nation-state, but at what cost? 17 Conclusion: “Peace in Our Time”? Slide 29 --How do we evaluate the Munich Agreement? --Neville Chamberlain called it “Peace in Our Time”, but we certainly know it wasn’t that. --Instead, Nazi domination of Europe plunged the world into one of the darkest chapters in human history. --Could anything have been done to stop this from happening? --More specifically, if Chamberlain and Daladier had stood up to Hitler in 1938 and even earlier would World War II have occurred? --Or if Benes had allowed his country to go to war would World War II have occurred. --These are important questions to ask when seeking to understand the origins and course of World War II. --They are important questions to examine when identifying when one country’s involvement in the affairs of another country is justified. --They are important questions to consider when discussing what makes democracy strong.