page 74 - The Antislavery Literature Project

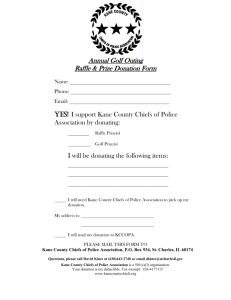

advertisement