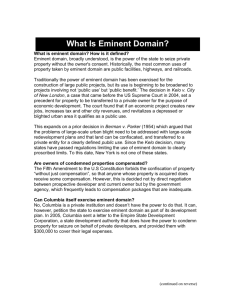

Takings 05 Kelo

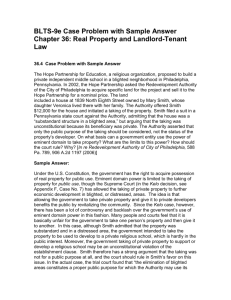

advertisement