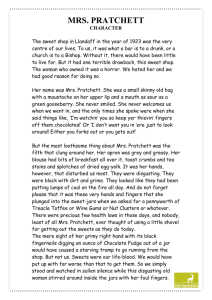

Thief Of Time

advertisement