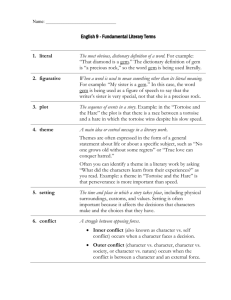

SAFER HIBERNATION & YOUR TORTOISE

advertisement

SAFER HIBERNATION & YOUR TORTOISE New Updated Edition Andy C. Highfield & Nadine Highfield In order to survive hibernation in good condition, tortoises need to have built up sufficient reserves of body fat; this in turn stores energy and water. Without fat and water tortoises die of starvation or dehydration. Adequate reserves of body fat are vital to tortoises in hibernation; they live off these reserves whilst asleep, and if the reserves run out too soon then the animal's body will begin to use up the fat contained within the muscles and internal organs, eventually these too will become exhausted. Should this occur the tortoise will simply die in hibernation. Very long hibernations are inherently dangerous. The smaller the tortoise, the more dangerous they are, as such animals have far fewer reserves than larger ones. In the past, many keepers used to give hibernation periods of up to four or even five months. This is one reason why so many tortoises used to die during hibernation. They simply ran out of energy reserves, or suffered dehydration. The other main cause of death in hibernation is freezing. Both of these hazards can be avoided if care is taken. This brief guide explains the steps you should take. Today, educated keepers intervene much more in the hibernation process and monitor everything closely. This is why a properly managed hibernation today is far safer than it used to be using the old methods. There is a simple method of checking to see if your tortoise is of adequate weight for hibernation. This is known as the Jackson Ratio graph. This graph must ONLY be used with the Hermann’s tortoise (Testudo hermanni) and Mediterranean Spurthighed tortoises (Testudo graeca and Testudo ibera). It must not under any circumstances be used with Horsfield’s or Russian tortoises (Testudo horsfieldii) or Marginated tortoises (Testudo marginata) as it will produce an entirely misleading result with them. If you are not sure what species you have, please consult a specialist vet or ask an expert from a tortoise organisation. It is extremely important to realise that whether or not a tortoise can safely hibernate depends on what species it is, and its geographical origin. This is why an accurate identification is so critical. Pet shops often sell tortoises that cannot be hibernated; common examples include Leopard tortoises (Geochelone pardalis), African Spurred tortoises (Geochelone sulcata), and Hingeback tortoises (Kinixys sp.). If you have such a tortoise, you will need to provide heated facilities throughout the year, especially over winter. Please visit our website and advice forum for further information on the special needs of tropical tortoises. There is only one way to take meaningful measurements for the purpose of computing the Jackson Ratio, and that is in a straight line. Any measurements taken ‘over the curve’ of the carapace will invariably produce a false result which will indicate that the tortoise's weight/length ratio is lower than it actually should be. This is the WRONG way to measure the length: This is the RIGHT way to do it: It is essential that measurements (and weights) are taken accurately, otherwise the result of the exercise will be meaningless, and may well endanger the tortoise. If the tortoise has a full bladder, you may not get an accurate weight reading. If you get an unexpected result, weigh it again a few days later. If you have a female tortoise which is not eating, but still seems very heavy, she may be carrying eggs. A tortoise which appears considerably overweight should be checked by a vet, and in the case of a female, this check should include an x-ray. On no account ever hibernate an underweight tortoise, or any tortoise which is ill or has recently been ill. Such animals are unlikely to survive. If in doubt, do not hibernate but keep awake and feeding over winter using artificial light and heat. We also do not recommend hibernating recently acquired tortoises. It is important that you are completely sure that the tortoise is 100% fit and healthy with no underlying problems. Pre-Hibernation Health Check It is wise to check your tortoise carefully, several times, in the run-up to hibernation. A few simple checks are recommended: CHECK BOTH EYES: for signs of swelling, inflammation or discharge. If there is a problem, consult a veterinary surgeon with extensive experience of treating reptile patients. CHECK THE NOSE: For signs of discharge; a persistently runny nose requires urgent veterinary investigation. Tortoises with this symptom must also be isolated from contact with others, as some varieties of RNS (’Runny Nose Syndrome’) are highly contagious. The presence of excess mucus also encourages bacterial growth, and hence places the tortoise in additional danger from diseases such as necrotic stomatitis (’mouth rot’). CHECK THE TAIL: For inflammation or internal infection; tortoises with cloacitis ‘leak’ from the tail and smell strongly. Any signs of abnormality should be investigated by a veterinary surgeon. It will help if you take a fresh sample of cloacal excretion for a veterinarian to examine under the microscope. CHECK THE SHELL: Look for any signs of fluid under the shell, or any soft or bad-smelling areas that could indicate ‘shell rot’ or necrotic dermatitis. CHECK THE LEGS: Look for any unusual lumps or swellings; abscesses are common in reptiles and if left untreated can result in loss of limb or even death. Report any unusual findings to a competent veterinary surgeon for further investigation. CHECK EARS: The membranes covering the inner ear should be either flat or slightly concave; ear abscesses are very common and can have fatal consequences if treatment is not obtained. The ear scales, the tympanic membranes, are the two large 'scales' just behind the jaw-bone. CHECK INSIDE THE MOUTH: Look for any sign of abnormality; necrotic stomatitis or ‘mouth-rot’ is a highly contagious disease of captive reptiles. It is characterised by the appearance of a yellow ‘cheesy’ substance in the mouth, or by a deep red-purple tinge, or by the appearance of small blood-spots. Sometimes all three symptoms are present. Expert veterinary treatment is called for as a matter of urgency if the animal is to be saved. These basic checks form your essential pre-hibernation examination. Provided your tortoise is up to weight and no other abnormalities can be detected, then you may begin preparation for hibernation. The golden rule, however, at all times is if in doubt seek expert advice. Not all vets are tortoise experts. Most tortoise organisations, however, do keep lists of vets with special experience in this area. Pre-Hibernation Fasting Period The key factors that initiate hibernation behaviour begin in late summer or early autumn. These environmental triggers include: Reduced ambient temperatures. The days become cooler with lower peak temperatures. Shorter day lengths. Reduced daylight intensity due to the lower position of the sun in the sky. As these conditions take effect, the tortoise will become less active, and less interested in feeding. We call this the ‘hibernation induction period’. If the weather is very poor in mid to late summer, then the tortoise may stop feeding too soon - if this looks like it is happening, you need to provide extra light and warmth to encourage continued feeding for a while longer. The further north you are situated, the more often this problem occurs. We suggest using indoor ‘basking pens’, or outdoor greenhouse-type accommodation where this is a problem. The main thing is to detect the problem early - it's too late to do anything about it after September. By then, the ‘winding down’ process will be well advanced. If a tortoise is underweight at this stage you will not be able to hibernate it safely, but must overwinter it in warm, light conditions indoors where it can continue to feed without being hibernated at all. This ‘fasting’ period may last for 3-4 weeks quite safely. We would recommend keeping the tortoise above 55º F (13º C) for at least 2 weeks after the last meal to allow time for food in the digestive tract to be processed properly; the most dangerous thing to do is to put a tortoise into hibernation (i.e. below 50º F (10º C) immediately after keeping it somewhere warm where it feeds normally. If this occurs, the digestive tract will contain large quantities of semi-digested food and the tortoise is in grave danger. In essence, the food can ‘rot’ internally producing dangerous gasses and toxins. Important points: THE LARGER THE TORTOISE, THE LONGER THE TIME REQUIRED TO DIGEST FOOD IN THE STOMACH Large tortoises (in the 2-3Kg range) will require about 1 month fasting period. Medium-sized tortoises (in the 1-1.5 kg range) will need about 3 weeks. Small tortoises (less than 1 Kg) typically require a fasting period of 2 weeks. We would not recommend fasting for less than 2 weeks, even for very small animals. All of these periods are temperature dependent. At low temperatures, the digestive tract slows down and it will take longer to digest the food in the stomach. At higher temperatures, the process is faster. That is why we recommend the temperature above, because it is low enough to suppress feeding, but high enough to permit continued digestion. Keeping the tortoise outside (if temperatures are safe) for the first half of the induction period, and then in an unheated room (again, provided temperatures are suitable) for the last half of the ‘winding down’ period is usually very effective. It will become less and less active, and more and more ‘sleepy’. Eventually, it will not emerge from its sleeping quarters very often at all. This is when we consider it ready for hibernation. Note that while tortoises should not be offered food during this period, they should be offered water by soaking (as described later) at least 3 or 4 times per week. Drinking is essential not only to ensure adequate hydration in hibernation, but also to ‘flush’ urates from the bladder. PREVENTING FROST DAMAGE IN HIBERNATION Over the last few very severe winters in the UK, very many tortoises that were hibernated in sheds, lofts, outbuildings or even unheated rooms in the house have either frozen to death or emerged after hibernation frost-blinded. If you have a tortoise in a box that has been placed in a shed, for example, to hibernate and temperatures drop to -26 C as they have done in some parts of the UK, that tortoise has very little chance of survival. It is absolutely critical that a tortoise is never exposed to freezing temperatures, even for a short time. Hibernating tortoises in ‘warm’ rooms is not the answer, as high temperatures also cause problems. Once the temperature rises to around 10 C, the tortoise will begin to use up fat and energy at a vastly increased rate and may be left with insufficient reserves to survive hibernation. The solution is to hibernate at a temperature low enough to conserve energy, but not so low as to risk freezing. For Mediterranean tortoises, the hibernation temperature needs to be maintained as close as possible to 5 C at all times, day and night. There are three main methods of hibernation. Each has advantages and disadvantages. Hibernation underground This method can work, but is highly dependent upon the locality, and especially upon the soil texture and consistency. It works best in sandy, welldrained soils. Dense clay soils are not well suited. Major drawbacks are that it is impossible to inspect the tortoise regularly, it may be vulnerable to rodent attack, and if the soil is too wet or damp it could die. On the positive side, buried tortoises rarely freeze. Best results with this method tend to be obtained when the tortoise buries down inside a dry greenhouse. This is a method so dependent upon location and soil texture, however, that it cannot generally be recommended for most keepers. Hibernation in a box This is the traditional method. Unfortunately, it is also associated with high levels of frost damage unless monitored extremely carefully. Tortoises that are hibernated in sheds, attics, unheated rooms and outbuildings can be subject to wide fluctuations in temperature. These temperatures can easily rise above 10C for extended periods, or drop to (or below) the lethal freezing point. Refrigerator hibernation Many keepers now use temperature-controlled hibernation environments based upon refrigerators (not freezers). Full details of how to do this are available on the Tortoise Trust website. If set up and monitored correctly, it has proven to be very safe and effective. If considering this method, it is essential that you follow the instructions carefully, and take expert advice. It is our view that this is presently the safest of all methods currently available. Never place the chiller or refrigerator in an unheated room or outbuilding where temperatures could fall below freezing. The temperature inside the unit will fall as well, and will not protect the animals within it from freezing. Dangerously low temperatures may be found on inside surfaces above refrigerant pipes or cooling surfaces towards the rear of the unit. Containers of animals should always be placed on the centre of shelves, well away from anything containing refrigerant. It is a very good idea to put a spacer made out of insulation material, such as thick polystyrene, between the tortoise container and the cooling surfaces of the refrigerator to prevent accidental contact. Most people who use this method place the tortoise in a plastic container filled with a natural type substrate of light soil and sand (a sealed container must not be used). The tortoise will naturally burrow into this substrate. It provides additional mass to help stabilise temperatures, and also helps to prevent dehydration. The top of the container needs to allow for air circulation, but at the same time, should prevent the tortoise escaping. If the tortoise did get out of the box in the refrigerator, it may fall and injure itself, or get too close to a dangerously cold area containing refrigerant. Controlled hibernation in a chiller-type refrigerator has proven consistently safe and effective. Do not rely upon old and unreliable units, however. Double check the accuracy of the thermostat before using an accurate electronic thermometer. Ideally, use two separate thermometers with remote probes. One should rest on the substrate next to the tortoise, the other should hang in free air within the unit. Check temperatures regularly. It is normal for the sensor in free air to show more fluctuation than the probe that is positioned next to the tortoise. Be aware that the possibility of a power supply failure needs to be taken into account if using such systems. Avoid refrigerators that include a freezer section, as in the event of a thermostat failure these can easily attain fatal sub-zero temperatures. The ‘drinks chiller’ type is preferable. Temperature stability within the unit will be improved by packing empty space with full water bottles to increase thermal inertia. The door should be briefly opened every couple of days to flush carbon dioxide and maintain oxygen levels. A small aquarium air pump tube can also be inserted through a break in the door seal to achieve the same objective. Check the air pump regularly to see that it is operating properly and that the air tube is in place. You can best ensure that adequate oxygen levels are maintained within the refrigerator by using both of these methods. If you do hibernate in an uncontrolled environment, however, your only defence against freezing or excessively high temperatures (resulting in too much energy loss) is to monitor the temperatures constantly, and be prepared to move the tortoise to a safe place immediately if temperatures stray outside the safe, permissible band. For practical purposes, we recommend taking action without delay if temperatures approach 2.5 C or if temperatures rise above 10 C for extended periods There is very little room for error at the lower end. If the tortoise’s body is exposed to 0 C even momentarily it will suffer frost damage and death in a very short time indeed. If temperatures threaten to fall to freezing point - move it immediately to a safe place. Short periods above 10 C will not do immediate harm, but extended periods above 10 C will rapidly deplete the tortoise’s energy (glycogen) reserves and put it in danger. It is quite safe to check a tortoise in hibernation for excessive weight loss, or for signs of dehydration. Most keepers agree that if much more than 1% of total weight is lost over a month, hibernation should be terminated. Any tortoise that has urinated in hibernation should also immediately be awakened, rehydrated, and overwintered in warm and bright conditions for the rest of the usual hibernation period. These animals are at extreme risk of fatal dehydration. Be especially alert for sudden and severe over-night temperature drops in December, January and February. The best way to check temperatures is by using two, totally independent thermometers positioned outside of the hibernation box. The reason we recommend two, not one, is that some thermometers are not very accurate, and to guard against failure. The best low cost thermometers we have found are the small electronic type. These can be readily obtained from many gadget, gardening and DIY stores. They run on a small battery that lasts for months. Some have a separate probe for easy positioning and others also feature built-in audible high and low temperature alarms. There are now also remote sensing’ thermometers that work by placing a sensor with transmitter in one location, and the readout (with receiver) in another - in the house, for example. These can work well, but it is vital to check them regularly. If the battery in the transmitter fails, or the signal is weak, they may fail to alert you to dangerous temperatures. We feel that while they are a useful addition to a standard thermometer, their risk of failure is too high to recommend them completely. It can also be helpful to monitor the temperatures inside the hibernating box, right next to the tortoise. For this, you need a thermometer with a remote probe. However, this should not be the main thermometer you rely on to judge hibernation safety. By the time this thermometer responds to a dangerously low temperature, it could already be too late! Use external thermometers, outside of the box, to maintain a safe environment. Never - ever - try to hibernate any tortoise without constantly monitoring temperatures using reliable thermometers. Remember, years ago few tortoises survived hibernation in captivity, these days losses are rare if the correct methods are used. This is entirely due to keepers adopting the methods described here. Juveniles, with their low body mass, are extremely vulnerable to rapid changes in temperature. One method of improving the temperature stability of juveniles is to allow them to bury into a dense, high mass of substrate just as they would in nature, but within a tray or container that can be placed in a temperature controlled environment. This will also assist with limiting fluid loss via the skin and respiration. The hibernation box We recommend ‘double boxing’ tortoises. This means using first an outer, larger box, then a smaller inner box positioned right in the middle with the intervening space filled with insulation material. Suitable material is shredded paper or polystyrene packaging chips. Hay or straw is not recommended as it often contains mould spores. Tortoises do move in hibernation (they will often try to ‘dig down’ as temperatures drop), and this prevents them digging too close to the outer side of the box where they lose the benefit of any insulation. Insulation only slows down the time it takes for severe cold to reach a tortoise. It does not stop it completely. So, no matter how well insulated your tortoise is, if your shed, attic or outbuilding is subjected to freezing conditions, your tortoise is in real danger. Move it. Do not make the fatal mistake of believing that because it is well insulated it is safe. It is not. Only by keeping ambient temperatures within a safe range can injury or death be prevented. This is why using thermometers and checking them frequently is so absolutely critical. Tortoises can be safely moved in hibernation. There is no truth to the belief that this is dangerous or harms them in any way. If temperatures threaten to go outside safe limits, the correct thing to do is to get them to a place where temperatures are suitable without delay. Be aware that rodents, and possibly other predators, will attack dormant tortoises. It is essential that all areas where tortoises are kept are rodentproof, and preferably, that any box containing animals is placed within a strong welded-wire cage. Animals placed in outbuildings or attics are at extreme risk. Severe injuries to the tail and limbs are commonplace if rats or mice gain access. Such attacks often prove fatal. All methods of hibernation require careful consideration by the keeper, and regular monitoring. You cannot simply put a tortoise away for the winter and forget about it. If you do that, it is very unlikely to survive. Hibernation today is much safer than it was, because keepers take it more seriously and check things on a continuous basis. Years ago, few tortoises survived even their first hibernation. Today, if correct procedures are followed, fatalities are rare. Hibernation period We recommend a minimum of 8-10 weeks for small tortoises, and no more than 16 weeks even for very large animals. This will require some intervention on your part and you will need to provide some artificial light and heat in early Spring. Post-Hibernation Care Tortoises only enter or remain in a biological state of hibernation (which is characterised by a depressed metabolic rate) while temperatures are within a certain range. The optimum range for the hibernation of terrestrial tortoises is in the range 4-6 degrees Celsius. As temperatures rise towards 10 degrees Celsius, the animal’s metabolic rate begins to return to normal, energy use increases, and the biological state of hibernation comes to an end. As the average mean ambient temperature begins to approach the critical 10 degrees C or 50 degrees F point, a tortoise’s metabolism will begin to reactivate in readiness for waking. Certain complex chemical and biological processes are initiated as the animal prepares to emerge into the spring sunshine. At this point, unfortunately, it often runs into its first problem. In Northern Europe, spring can be cold, wet, and miserable. For us, this sort of weather may be merely unpleasant. For tortoises it can present rather more serious problems. Upon first emerging from hibernation a tortoise is depleted in strength, has a low White Blood Cell (WBC) count, and is very vulnerable to infection. Glycogen (energy) reserves will also be very low at this time. Unless it receives adequate quantities of heat and light it will simply ‘not get going properly’, and instead of starting to regain weight and strength lost during hibernation, will refuse to eat, will use up its existing fat and energy reserves, and will begin to decline quickly. Do not make the fatal mistake of believing that ‘he does not want to come out of hibernation yet, it must be too early’ and put the animal back into hibernation. You will not be putting the animal into hibernation - in all probability you would be killing it. Hundreds of people do make this very mistake each year, and hundreds of tortoises die as a consequence. If the tortoise wakes up, and temperatures are approaching or above 10 C or 50 degrees F keep it awake. Do not return it to hibernation. Also, if you detect that the tortoise has urinated in the hibernating box, get it up and keep it awake too . As the temperature rises listen carefully to the hibernating box - you should begin to hear the first sounds of movement. Act quickly to get the tortoise up. Remove the hibernating box from its winter quarters and warm it up by placing it in a moderately warm room. After an hour or so remove the tortoise from its box and place it in a warm (+25 C), bright environment. A 150 Watt reflector lamp suspended about 40cm (15’) above the tortoise will make a huge difference. Do not expect a tortoise to begin feeding without this sort of artificial assistance in the UK. British spring weather is totally different from that in the Mediterranean. Tortoises must have extra light and heat at this sensitive time. Keeping the tortoise in the house, even if well heated, is still not likely to be sufficient unless a basking lamp of this type is also provided. They need to raise their body temperature to at least 30 degrees Celsius – far above normal room temperature. A simple basking lamp can make a huge difference – use one always! Both radiant heat and light in adequate quantity and quality are absolutely vital to get the tortoise functioning properly. We cannot stress this enough. It is not optional. It is essential! We receive numerous calls for help from people who tell us that their tortoise came out of hibernation ‘several weeks ago’ but ‘is not eating or doing much yet’. Our first question is ‘Do you have it in a nice warm, bright place with a basking lamp?’ The answer is almost invariably ‘No’. Every year animals die unnecessarily because this simple and low-cost step is ignored. There really is no excuse. Tortoises need light and heat. The method we describe here is the easiest and most effective way of providing it. It will cost you less than £15 to provide such a facility. Consider the veterinary costs that may be incurred if you do not! Hydration and drinking Many people experience problems in getting tortoises to drink - in fact almost all tortoises will drink provided water is offered in a suitable manner. We recommend placing the entire tortoise in a washing-up bowl filled with about 25 mm of tepid water - less in the case of very small tortoises, a little more for larger animals. The depth should be about chin height. Simply offering a small dish of water to the tortoise is not likely to stimulate a good drinking response, but actually placing it in water is usually successful. Splashing water on the shell and around the head also often helps. Drinking is, at this stage, far more important than feeding. Both dehydration and the presence in the renal system and bladder of toxins dictate that every effort must be made to encourage drinking first, feeding later. The tortoise must also be kept warm as described previously - it is absolutely vital that such temperatures are maintained in order to speed up activation of the tortoise’s digestive system. As the tortoise awakes, certain biological changes take place; one of the most important of these is the release into the bloodstream of a chemical called glycogen, which has been stored in the liver. This provides extra energy to give the tortoise an initial ‘boost’. Feeding must take place before this is exhausted, or the animal will begin to decline. The glycogen level can be artificially boosted by providing water with glucose in solution daily - about 2 teaspoons per 250 ml dilution, at about l0-20 ml per day for an average sized animal. Do not continue this therapy indefinitely, or dangerously high blood-sugar levels may be attained. Four or five days maximum should be sufficient. All tortoises should very definitely feed within ONE WEEK of emerging from hibernation. If they do not there is either: A health problem such as frost damage. A husbandry problem (usually lack of heat and light) If your tortoise is not feeding by itself within one week of waking up (provided the correct conditions are present) do not delay any longer - consult a veterinary surgeon that has particular experience of reptile husbandry Good diagnostic techniques, combined with an understanding of reptile metabolism and function, will invariably produce a satisfactory answer. Whatever you do, please do not delay. A tortoise which refuses to feed after a week or more of correct temperatures definitely has a veterinary problem that requires professional investigation. Delay in these circumstances can result in the loss of your tortoise, as it is especially vulnerable at this time. In most cases, however, if you provide suitable conditions, with adequate heat and light, and ensure adequate hydration, your tortoise will make a very fast recovery from its winter sleep and will soon begin feeding normally. Further advice and information can be obtained at www.tortoisetrust.org or www.britishcheloniagroup.org