Workers and Their Organisations

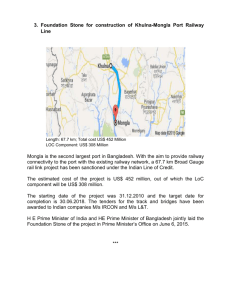

advertisement