101.Ch 6. Mankiw

Ch 6. Supply, Demand and Government Policies -- Mankiw -- Principles of

Microeconomics

I. Introduction a. Overview – Chapter focuses on public policy analysis using tools of supply demand. One theme: unintended consequences – anticipate using S & D analysis

-- Consider price controls (e.g., rent control, agric price supports, min wage) and the impact of taxes.

II. Controls on Prices a. Causes – most often the result of interest group politics. We will examine cases of this later. b. Definitions – price ceiling – a legal maximum on the price at which a good can be sold.

– price floor – a legal minimum on the price at which a good can be sold.

III. How Price Ceilings Affect Market Outcomes a. Two Possible Outcomes – Ceiling is: 1. not binding; or 2. binding. If a ceiling is BELOW the equilibrium price that would prevail but for the ceiling, it is binding. Otherwise, it is not. b. Figure 1 – panel (a) – Ceiling at $4 -- not binding. Market forces naturally move the price to $3 and a restriction on sales above the price of $4 has no effect on either the price or quantity sold.

– panel (b) – Ceiling at $2 -- binding. Market forces would naturally move the price to $3 but a restriction on sales above the price of $2 prevents this. Thus, the market price equals the price ceiling. At this price, the quantity of ice cream demanded (125) exceeds the quantity supplied (75). That is, there a shortage of 50

– 50 people who wanted ice cream at the $2 are unable to get it. c. Consequences – because in the case of a binding price ceiling, price can’t serve as a mechanism to ration the good, some other mechanism will naturally develop. Possibilities:

1. Long lines (queuing) buyers who are wiling to arrive early and wait get the item – others do not.

2. Sellers’ personal biases – sell only to friends or members of their own racial or ethnic group.

-- Notice that although the policy was developed to help buyers not all buyers benefit – Some buyers get to pay the lower cost although they may need to stand in line (& pay an implicit cost), but others get nothing at all.

General result: when the government imposes a binding price ceiling on a competitive market, a shortage arises and sellers must ration the scarce goods among a large number of potential buyers. d. Other Consequences – 1. emergence of black markets; 2. reductions in quality; 3. policing and enforcing costs; and 4. reduction in investment. Black markets emerge because both sellers and some buyers would like a higher price. Both therefore have an interest in evading the restrictions. To keep the restrictions in place, governments must incur policing and enforcing costs. Quality reductions occur b/c sellers can cut quality and still sell all they want at the ceiling price. Investment is reduced b/c producers can’t earn a market return on their capital – move to a market w/ better returns e. Inefficiencies – the rationing mechanisms that develop under price ceilings are rarely desirable. Long lines waste time. Policing and enforcing wastes resources.

IV. Case Study: Lines at the Gas Pump a. History – as explained above – OPEC restricts supply of oil in 1973. Higher oil prices caused higher gas prices and lines formed at gas stations everywhere. b. What Caused the Gas Lines? Many blamed OPEC. And in fact the lines would not have occurred but for the OPEC price increase. However, price ceilings on gas were a necessary ingredient. c. Figure 2 – shows what happened. Panel (a) shows the situation before the OPEC price increase – a nonbinding price ceiling w/ price at P1. Panel (b) shows the situation after the OPEC increase. Supply shifts from S1 to S2. In an unregulated market, price would rise to P2 (w/ no shortage). However, the ceiling prevents this. Shift in supply caused the shortage at the regulated price. Eventually, the laws regulating the price of gas were repealed.

V. Case Study: Rent Control in the Short Run and Long Run a. Rent Control Basics – rent control is a common example of a price ceiling. Goal: make housing more affordable.

1

b. Economic View – argue that rent controls are a highly inefficient way to help the poor. Effects of rent control not obvious b/c they occur over many years. In the short run, landlord have a fixed number of apartments to rent and they can’t adjust this number quickly as market conditions change. Also, the number of people searching for housing in a given city may not be highly responsive to rents in the SR b/c people take time to adjust their housing arrangements. (SR demand and supply are relatively inelastic.) c. Short Run Effects -- Figure 3 – panel (a) shows the short run effects of rent control on the housing market. Because supply and demand are inelastic in the SR, the initial shortage caused by rent control is small – primary effect is to reduce rents. d. Long Run Effects -- Figure 3 – panel (b) shows the long run effects of rent control on the housing market. Supply & demand more elastic because:

-- Landlords respond to rent controls by not building new apartments and failing to maintain existing ones.

On the demand side, low rents encourage people to find their own apartments or to move to the city. With the more elastic supply and demand, a large shortage of housing results.

-- In cities w/ rent control, landlords use various techniques to ration housing: 1. long waiting lists; 2. give preference to tenants w/o children; 3. discriminate based on race; and 4. accept under the table payments.

--The existing housing stock also deteriorates b/c landlords can rent run-down apartments at the same price as well-maintained apts.

-- Policymakers also react to the effects of rent control by imposing additional regulations. For instance, laws that make racial discrimination illegal may need additional enforcement.

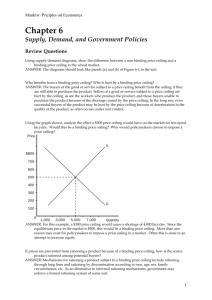

VI. How Price Floors Affect Market Outcomes a. Two Possible Outcomes – Floor is: 1. not binding; or 2. binding. If a floor is ABOVE the equilibrium price that would prevail but for the floor, it is binding. Otherwise, it is not. b. Figure 4 – panel (a) – Floor at $2 -- not binding. Market forces naturally move the price to $3 and a restriction on sales below the price of $2 has no effect on either the price or quantity sold.

– panel (b) – Floor at $4 -- binding. Market forces would naturally move the price to $3 but a restriction on sales below the price of $4 prevents this. Thus, the market price equals the price floor. At this price, the quantity of ice cream supplied (120) exceeds the quantity demanded (80). That is, there a surplus of 40 – 40 units of unsold output (purchasing surplus). c. Consequences -- Just like the price ceiling, price floors may lead to undesirable rationing mechanisms.

– The consequences of a price floor depends on how the floor is established. The government may use either a mandate or it may purchase the surplus. Mandate: disguised discounts, underinvestment, policing and enforcing costs, unemployment. Purchasing surplus: storage costs, overinvestment, surplus.

VII. Case Study: The Minimum Wage a. History – minimum wage laws dictate the lowest wage that an employer may pay. The US Congress first instituted a minimum wage w/ the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 to ensure workers a minimally adequate living standard.

-- In 2005, the minimum wage was at $5.15/hr & some states imposed higher minimum wages. b. Analysis – Figure 5 – panel (a) shows supply and demand for labor. Workers supply labor & firms determine the demand. If government doesn’t intervene, wage goes to equilibrium.

Panel (b) - shows the market with a minimum wage. If the minimum wage is above the equilibrium level, the quantity supplied (of labor) exceeds the quantity demanded (i.e., unemployment). Thus, the min wage raises incomes of those who keep jobs but lowers the incomes of those who lose jobs. c. Heterogeneous Labor – above analysis simplifies by assuming a single labor market – in reality there are many different labor markets based on skill & training. Impact of the min wage depends on skill & experience – only low-skilled workers affected by current minimum wage (especially teen workers). For highly skilled workers, the min wage is not binding. d. Measuring the Effect of the Minimum Wage – many economists have studied how the min wage affects the teen labor market. Some debate about the magnitude – but the typical study finds that a 10% increase in min wage decreases teenage employment between 1 and 3 percent. In interpreting this estimate, note that a

10% increase in the min wage does not raise the average wage of teens by 10% -- law doesn’t affect those paid above the minimum and enforcement is not perfect.

-- In addition to affecting labor demand, min wage raises the amount teens can earn & the number of teens who want a job.

2

-- Studies have found that raising the min wage influences which teens are employed. Increases in min wage increase the dropout rate. The new dropouts displace other teens who had already dropped out & now become unemployed. e. Politics of the Minimum Wage – Min wage advocates – see the min wage as a way to raise incomes of the working poor. Correctly point out that min wage workers can afford only a meager standard of living.

(In 2005, w/ min wage at $5.15, two adults working 40 hrs a week earn only $21.4k a year – less than half the median income.) Advocates often admit min wage causes unemployment but they believe the effects are small & all things considered poor will be better off w/ higher min wage.

-- Min wage critics – claim that it’s not the best way to combat poverty b/c it causes unemployment, causes teens to dropout of HS, and prevents some unskilled workers from getting the training they need. Also, the min wage is poorly targeted -- not all min wage workers are heads of households. In fact fewer that 1/3 of min wage earners are in families w/ incomes below the poverty line. Better to use a wage subsidy (e.g.,

EITC).

VIII. Taxes a. Motivation – all governments use taxes to finance public projects. b. Tax Incidence – suppose government finances parade w/ a tax of $0.50 on good X. Producers argue that buyers should pay b/c they operate on razor thin margins. Consumers argue that sellers should pay.

-- Definition: the distribution of the burden of the tax among participants in a market. Who pays? Buyers or sellers?

IX. How Taxes on Buyers Affect Market Outcomes a. Figure 6 – suppose that government passes a law that levies a $0.50 tax on buyers of a good.

1. Initial impact is on the demand for the good b/c buyers must pay the tax. Supply not affected.

2. Because the tax makes buying the good less attractive – demand shifts left. Since the tax is $0.50, the effective price is now $0.50 higher than the market price. Thus, the tax shifts the demand curve leftward

(vertical) from D1 to D2 by the amount of the tax ($0.50).

3. From the figure we see that the price of the good falls from $3 to $2.80 and quantity falls from 100 to 90 b. Implications – Because price falls by $0.20, sellers receive $0.20 less per item than they did before the tax. Tax makes sellers worse off. Buyers pay a lower price, but the effective price is $3.30 ($2.80 + $0.50).

The tax also makes buyers worse off.

Two lessons: 1. taxes discourage market activity – quantities fall; 2. Buyers and sellers share the burden of taxes.

X. How Taxes on Sellers Affect Market Outcomes a. Figure 7 – suppose that government passes a law that levies a $0.50 tax on the sellers of a good.

1. Initial impact is on the supply for the good b/c sellers must pay the tax. Demand not affected.

2. Because the tax makes selling the good less attractive – supply shifts left. Since the tax is $0.50, the effective cost is now $0.50 higher than the market price. Put differently, to induce sellers to supply any given quantity the price must be $0.50 higher. Thus, the tax shifts the supply curve leftward (vertical) from

D1 to D2 by the amount of the tax ($0.50).

3. From the figure we see that the price of the good rises from $3 to $3.30 and quantity falls from 100 to

90. b. Implications – Because price rises by $0.30, buyers must pay $0.30 more per item than they did before the tax. Tax makes buyers worse off. Sellers receive a higher price compared to pre-tax, but the effective price falls from $3.30 to $2.80 ($3.30 - $0.50). The tax also makes sellers worse off.

Once again, we draw two lessons: 1. taxes discourage market activity – quantities fall; 2. Buyers and sellers share the burden of taxes.

-- Compare Figures 6 and 7 – surprising conclusion – taxes on buyers and sellers are equivalent. In both cases, the tax drives a wedge between what buyers pay and sellers get to keep. The wedge is the same regardless of whether the tax is levied on buyers or sellers. The only difference is who sends the money to the government.

3

XI. Can Congress Distribute the Burden of a Payroll Tax? a. Payroll Taxes – one key payroll tax is called FICA (Federal Insurance Contribution Act). The government uses this revenue to finance Social Security and Medicare. Tax is levied as a percentage of wages. In 2005, total FICA tax for the typical worker was 15.3% of earnings b. Burden of FICA – When Congress passed the FICA tax, it tried to mandate a division of the tax burden.

According to the law, half the 15.3% is paid by firms out of their revenues and half is paid by workers (by paycheck deduction). c. Analysis – shows that the government can’t easily mandate the distribution of the burden. To illustrate, we can analyze a payroll tax in the same way as a tax on a good (where the good is labor). The key feature is that the payroll tax drives a wedge between what firms pay for labor and what workers receive. d. Figure 8 – shows the outcome – payroll tax cuts workers’ receipts & raises what firms pay. Division hs nothing to do w/ legislation – instead it is relative supply and demand elasticities.

XII. Elasticity and Tax Incidence a. Figure 9 – varies the relative demand and supply elasticities to show that sellers bear more of the burden when supply is relatively less elastic. Buyers bear more of the burden when demand is relatively less elastic. Less elastic implies fewer options & fewer options means greater share of burden. Elasticity measures the willingness of buyers or sellers to leave the market when conditions are unfavorable. A small elasticity of supply means that sellers do not have good alternatives to producing this particular good. b. Panel (a) shows relatively elastic supply & relatively inelastic demand. Because sellers are very responsive while buyers are not most of the burden is shifted to buyers. Price received by sellers doesn’t fall much but price buyers pay rises a great deal. c. Panel (b) shows relatively elastic demand & relatively inelastic supply. Because buyers are very responsive while sellers are not most of the burden is shifted to sellers. Price received by sellers falls a great deal but the price buyers pay doesn’t rise much. d. Implications for Payroll Taxes – most labor economists have found that the supply of labor is much less elastic than the demand. This means that workers rather than firms bear most of the burden of the payroll tax – like panel (b).

XIII. Who Pays the Luxury Tax? a. History – in 1990, Congress adopted a new luxury tax on items like yachts, private aircraft, furs, jewelry, and expensive cars. Goal was to raise revenue by taxing the rich. b. Effect – Forces of supply and demand vitiated Congresses intent. Consider yachts – demand for yachts is rather elastic. Millionaires can easily spend money on other items. Supply is relatively inelastic. Yacht factories are not easily converted to other uses & workers who build yachts are not eager to change careers.

Consequently, the burden of the tax will fall primarily on forms and workers who build yachts. Suppliers of these luxury goods made Congress aware of their plight and the tax was repealed in 1993.