Market Orientation for a Constituent

advertisement

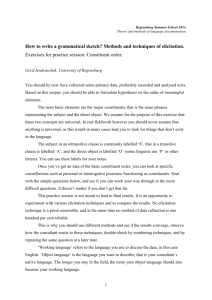

Constituent Market Orientation Published in Journal of Market-Focused Management Issue 4.2. Summer 1999, p 103-124 Brynjulf Tellefsen Associate Professor The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing P.O. Box 4676, Sofienberg N-0506 Oslo, NORWAY E-mail: brynjulf.tellefsen@bi.no Fax: +47 – 22 98 51 11 Phone: +47 – 22 98 50 00 Address all questions to the author at above address Constituent Market Orientation Abstract This paper expands the scope of a market orientation from downstream markets to most of the major constituents of the firm. In so doing this paper addresses four questions: 1) Can constituent market orientation be measured based on modifications of the theory, concepts and measurement scales developed by Kohli and Jaworski (1990, 1993)? 2) What are the antecedents for a constituent market orientation? Are they similar across constituents? 3) What are the consequences of constituent market orientations? Which are unique for a constituent? Which stem from the sum of orientations towards all constituents? 4) What are the historic and situational moderators of orientations and consequences? Key words: Constituent Orientation Norwegian Utilities Industry Market Orientation Effect of Deregulation Organization Learning Business Culture Introduction Numerous studies have been made on market orientation. Most authors focus on the degree to which a business unit’s culture is responsive to downstream markets. Some work has been done on upstream markets. To some extent other constituents of the firm have been accounted for as antecedents and moderating factors. The heavy downstream focus in market orientation studies is problematic. It may lead to sub-optimization and unnecessarily limit the scope of marketing thought and practice. Firms depend on a series of inter-connected markets in order to do business. Many constituencies and stakeholders determine the market value of a firm. They are the labor markets including employees and labor unions, the finance markets including equity owners and lenders, the upstream markets including suppliers, the market regulators in industry associations, local and national government, general market influence groups like the media, and downstream markets including customers. The firm faces competition in all these markets. 103 The purpose of this paper is to expand the scope of a market orientation to include the major constituents of the firm. In so doing this paper addresses four questions: 1) Can we measure constituents market orientation based on modifications of the theory, concepts and measurement scales developed by Kohli and Jaworski (1990, 1993)? 2) What are the antecedents for a constituent market orientation? Are they the same across constituents? 3) What are the consequences of constituent market orientations? Which are unique for a constituent? Which stem from the sum of orientations towards all constituents? 4) What are the historic and situational moderators of orientations and consequences? The paper is organized as follows: The orientation concept is discussed and defined as a behavioral double-loop learning for the firm, and for each of the major constituencies based on existing literature. The first attempt of modeling constituent orientation in 1994 by Tellefsen (1995) is referred in some detail. A model of the constituent market orientation among the newly deregulated Norwegian electric utility companies is developed. The methods used in the investigation of the Norwegian electric utilities are explained. Findings of the survey on the constituent market orientation of the utilities are presented. Antecedents and exogenous situational conditions affecting the degree of constituent market orientation, as well as the consequences are investigated for each major constituent and for the combined set of constituents. To highlight the effects of a unique industry history and situation on the various constituent orientations, a comparison with previously published research on the constituent market orientation of the largest corporations representing a broad cross-section of industries in Norway are also shown. Interrelations between consequences of a constituent orientation are investigated. The paper ends with a discussion of the findings, and their managerial and research implications. The Orientation Concept Consciousness is limited. If an individual is preoccupied with something because of his previous learning of beliefs, values, priorities, goals and habits, other parts of reality become unattended to, invisible or incomprehensible. The same may occur at the group level to the extent mental frames, observations and experiences are shared. Cultures and subcultures are formed, depending on the extent and patterns of double-loop learning. Every firm therefore develops a distinct business culture more or less homogeneous and stable over time (Allaire and Firsirotu, 1984, Bate, 1984, Mitroff, 1975, Schein, 1985). An orientation can be seen as a particular subculture with an identifiable set of cognitions developed around a particular solution for a group. There are many possible cultural states. Orientations towards Society, Power, Politics, Ideology, Ideals, Personnel, Bureaucracy, Profits, Resources, Environment, Suppliers, Production, Product, Sales, Competitors, Customers, and Markets have been identified and described (Tordis Buen, 1996). 104 Orientations can be described on several dimensions. In a constituent oriented organization signals are picked from all parts of the environment, especially from the firm’s stakeholders. Focus is on win-win, the driving force is market behavior optimization, and the goal profitability via value creation for others. It is long-term, interactive, integrative, harmony seeking and materialistic in nature. The main success factor is the organization’s ability to gather, spread and react quickly and correctly to environmental signals. Reality is subjective and a social construction, perception of man is positive, communication is interactive, the values are instrumental, and social competency is important. A constituent orientation implies that the organization is network oriented. Both internal and external constituents are treated as markets. Where the need for vertically administered exchange solutions is great, the stakeholders may think in terms of ownership control. Where competition and flexibility of partnership choice is important, the legal and social relationship between the parties will be much less binding. In real life these orientations normally do not exist in their extreme state, but are mixed with each other, forming subcultures where overlaps define the common cultural base. It is therefore appropriate to conceptualize the constituent orientation of a firm as one of degree, on a continuum, rather than as being either present or absent. A business unit or a work group will normally have a culture and orientation that deviates more or less from that of the firm as a whole and other groups. This is partly based on unique access to signals and experiences with specific constituents of the firm. If these unique learning channels are not opened up to colleagues in other business units and work groups through well functioning double-loops of learning within the firm, the formation of subcultures will be strong, and the common culture base weak. If the commonalties in culture and orientation are great, the firm has a strong culture in the sense that members of the firm will act in the same manner and more easily together to signals from the central leadership group or from the surrounding markets. If the business units and work groups have little common culture, they may each and all be closer to their particular external markets, but have great difficulty in communicating and acting together. It is therefore important to measure and understand constituent market orientation at the corporate, business unit and work group levels. An organization’s orientation will normally change slowly, and have a tendency to be reinforced as long as results achieved are deemed satisfactory. In times of crisis, the ruling paradigm of the organization may change quickly, and the mix of orientations change accordingly. External forces normally generate the need for change, but the implementation of changes is an organization-internal process. The internal change process are programmatic or a systemic market-back learning (Slater and Narver, 1995). In programmatic processes the leadership executes learning activities designed to change the cultural elements of the organization. The immediate effect can be great, especially if the significant actors are in agreement and are persistent in their efforts. Programmatic activities happen outside the daily task-handling system. The programmatic efforts will lose their effect if not translated into permanent changes in the way every employee thinks and acts in their daily task. To obtain a lasting and accelerating reinforcement process of the new orientation, the programmatic actions must be combined with a reengineering of the internal and external architecture of the organization. The 105 daily task handling system generates the feedback for continuos individual learning. The organizational architecture determines the nature of double-loop learning. This line of reasoning can be extended to networks of cooperating firms and business units (Cravens and Piercy, 1995, Payne 1988). For cultural learning to take place it is sufficient that the exchange partners have mutual commitments for value creation and a minimum of contact. Common ownership is not a necessary condition. The long-term effects of double-loop learning between business partners are manifested as industry cultures, cultures of professions, customer cultures influencing business unit cultures, etc. Market Orientation for a Constituent Jaworski and Kohli developed and measured a behavioral model of a learning process that leads to a higher degree of downstream market orientation (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990, Jaworski and Kohli, 1993). Top management signals are programmatic inputs to the learning process. They do not explicate other programmatic inputs for change. The other antecedents are treated as internal situational factors in their model. If the leadership want to change the double-loop learning in their organization, they have to initiate programmatic systems reengineering to change these antecedents. The environment is only taken account of as moderators to consequences, and not to antecedents. Business culture research indicates that the firm’s history and changes in the environment also should be treated as antecedents to the programmatic reorientation and the continuous learning processes. Market orientation is defined as a three stage behavioral process that provides continuous internal and external double-loop learning with the downstream markets. Tellefsen expanded this model to measure the degree of market orientation and its antecedents and consequences towards other constituencies (Tellefsen, 1995). The overall market orientation and towards each of six constituencies was measured in 1994 using Jaworski and Kohli's concepts, modifying their questions by referring to relevant actors in the relationship. Respondents were the managers responsible for the five constituent relationships plus the main labor union representative in the firm. Questions about the antecedents were repeat measured for all the managers. 235 CEOs answered questions relating to the total business environment. 244 marketing managers in the firm’s largest business unit answered questions related to downstream markets. 188 purchasing managers in the firm’s largest business unit answered questions related to upstream markets. 163 personnel manager and 179 union representative answered questions related to the firm’s leadership, organized and unorganized employees and the labor markets. 154 PR manager answered questions related to the media and the public. 175 lobbying manager answered questions related to the national government. Questions identifying results specific to each constituency relationship were added, and answered by the manager responsible for the relationship. The CEOs answered the general business performance questions. Market orientation towards other possible constituents was not measured. To convert the measurement scales from the customers to other constituencies, theory of general management, purchasing, lobbying, public relations, personnel management and labor relations were studied and compared with marketing theory. The functional theories had striking similarities at both the strategic, tactical, inter- and intra-organizational levels. 106 Names of actors, some activities, and results sought varied, but methods and the meaning and content of theoretical constructs were virtually identical across the functional literature. Identical market orientation constructs could therefore be applied to all constituent learning loops. The 1994 investigation (Tellefsen, 1995) showed that the modified Jaworski and Kohli measurement model was able to identify the degree of market orientation towards each of five constituents via the managers responsible, as well as the general constituent orientation of the CEOs and the labor union leader’s constituent orientation. Few antecedents were measured. Those measured influenced all the seven constituent orientations in the same way. A series of consequences specific to each of the seven constituency orientations were identified. Due to a lack of overlap of competed questionnaires within firms, the sample did not allow a test of the combined antecedents and consequences of market orientation held by the leadership group of each firm. Nor did the sampling methodology allow identification of the impact of historic and situational factors on the orientations and their consequences. In order to correct some of these weaknesses a new sample of the newly deregulated Norwegian utilities was investigated in 1995. For economic reasons the investigation of labor union representatives was dropped. Most orientation questions were repeated to allow a comparison between the two surveys. The Model of Constituent Orientations for Norwegian Utilities A revised model of a firm’s constituent orientation with antecedents and consequences was designed for the new investigation of Norwegian utilities. It is shown in figure 1. The constituent market orientation is defined as a one-dimensional behavioral learning circle consisting of the gathering and dissemination of information pertaining to the constituents’ current and future needs, and the organization’s coordinated response based on this information. This is an extension of the Kohli and Jaworski definition of a market-back learning circle to constituents other than the downstream market. The constituent market orientation is measured as the sum of the leadership group’s self-reported market orientations towards internal and external constituents of the organization. A theoretically weaker measure of the same was also used: the CEO’s self-reported constituents market orientation. Five partial constituent orientations are operationalized as one-dimensional learning circles pertaining to current and future needs of customers, suppliers, employees, the media and public, and members of the national government. The following hypotheses were formulated based on existing theory and research: Hypothesis 1: The total constituents market orientation and the orientation towards each of the five constituencies have similar antecedents. The constituent orientation is higher if: H1a: the personal background of the leadership group is varied and other-directed, H1b: the risk tolerance in the leadership group is high, H1c: the signals from the leaders are many, strong and consistently market oriented, 107 FIGURE 1 A Model of Constituent Market Orientation EXTERNAL ANTECEDENTS: Historic and Currently Partial Monopoly, Main Product a Commodity INTERNAL ANTECEDENTS: (Measured through the following respondents) Five Functional Managers The CEO All Six Managers Interdepartmental conflict, connectedRisk tolerance, Reorientation Personal backgrounds ness and departmentalization Senior management signals (Variety is calculated) Hierarchy (delegation degree) Relative priority of constituents CONSTITUENT MARKET ORIENTATIONS Five Functional Managers The CEO Market orientation toward their own constituent measured Market orientation towards as gathering, disseminating, and reacting on intelligence all constituents. CONSTITUENT MODERATORS Government Lobbying competition intensity The firm’s importance for the government Regulation changes in the firm’s industry Customers Turbulence among customers Competitive intensity among customers Suppliers Turbulence among suppliers Competitive intensity among suppliers Differentiation between suppliers Media Turbulence among media Competition to get into media Availability of media Media knowledge in the industry Employees Turbulence in the employment market Employment competitive intensity Negotiation power of employees Negotiation power of union representatives Government influence on relations PR Influence on 3rd parties Information from media Personnel Employee loyalty Employee compensation Customer effect Level of “lassies-fair” Level of trust Unionization percentage 108 ORGANIZATION MODERATORS The CEO Generic strategic choice of the firm Lobbying manager Dependence on government decisions Ability to influence top management Marketing manager Technological turbulence Ability to influence top management Centralization of marketing decisions Purchasing manager Time horizon for investments Ability to influence top management PR manager Centralization of PR decisions Ability to influence top management Personnel manager Turbulence among employees Recruitment needs Focus on retaining employees Salary level in the industry Centralization of personnel management Ability to influence top management CONSEQUENCES OF THE ORIENTATIONS Purchasing Lobbying Cooperation level Increase in lobbying Relative purchasing costs Influence on government Profit margins Labor union support The CEO Return on total assets Return on equity Relative per unit cost level Marketing Customer loyalty Customer satisfaction Market share Marketing costs Profit margins H1d: the members of the firm’s value chain are given priority over other constituencies, H1e: the internal conflict level is low, H1f: the interdepartmental connectedness is high and the departmentalization is low, and H1g: the degree of hierarchy is low (the degree of delegation is high). Hypothesis 1 is based on the belief that a market-oriented firm has an organic view of business. The organization is a life form that lives in a symbiosis with its environment. The firm cannot be socially justified, understood nor survive unless it has positive exchanges with every salient part of its environment. Sub-hypothesis H1a follows directly from this view. In sub-hypothesis H1d it is assumed that the closer to the firm’s value core the focus is the more the people in the organization learn about the most important constituents for the firm’s value creation, which raises the overall constituent market orientation. The other sub-hypotheses are extensions to all constituency orientations of Jaworski and Kohli's hypotheses and findings regarding downstream market antecedents. Hypothesis 2: The history and nature of the firm and its industry will influence the observed constituent orientations and their antecedents. These factors may have different impacts on the market orientation towards each of the constituencies. Existing research strongly suggest that cultures are lasting. The specific hypotheses are a consequence of the utility industry’s historic total monopoly and their current distribution monopoly, and the commodity nature of their main product. The utilities have not had the need for a downstream market orientation, and could not make money on it because of the difficulty of developing a unique selling proposition based on value differentiation. The current downstream market orientation is expected to be very low. Their former and partially current ability to pass on labor and upstream market inefficiencies to the customers should lead to a low employee and supplier orientation. Their authority and media orientation may be higher due to the relatively tight governmental regulation and heavy involvement in the industry, and the important social position they have as utilities. Norway has the second highest electric power production per capita in the world, and utilities are the cornerstone enterprises in many local communities. I test these hypotheses by comparing the survey of the utilities in 1995 with the 1994 survey of large Norwegian firms across industries (Tellefsen, 1995). H2a: The utilities will have a low total constituent orientation, and a low customer, employee, and supplier orientation compared to the average of business enterprises. Their authority, media and public orientation will be higher than the average of large Norwegian firms. Since the deregulation is recent compared to the timing of the data collection the utilities will be spending much time and effort on programmatic market orientation and changes in 109 organizational systems and architecture as an answer to the new price competition in the downstream markets. H2B: The utilities will score high on antecedents relative to other large Norwegian firms. Hypothesis 3: A higher constituent orientation produces higher returns on investments and lower total unit costs. The effect becomes stronger with the presence of turbulence, competition and differentiation opportunities. The first part of the hypothesis is well supported in several reported studies on downstream market orientation. Since the constituent orientation takes into account all markets that influence profitability, the profitability consequence should be strong and not modified by any environmental or situational factors other than the degree of turbulence and competition and the opportunity to differentiate from competitors. In addition, a high degree of environment-driven learning should lead to more efficient firms. The rationalization effect should be separately observable. The correlation with return on equity should be weaker, due to the extensive local and central government ownership of Norwegian utilities. Equity is often based on historic costs and not current asset values, as the government owned utilities do not have to show real asset values to the equity and loan markets. Hypothesis 4: The consequences of the market orientation towards each of the constituencies differ from each other. Each consequence has a unique partial contribution towards the total value generating ability of the firm. Specifically: H4a: A high downstream market orientation leads to higher customer loyalty and satisfaction, which in turn may lead to higher market shares and profit margins and lower marketing costs. H4b: A high upstream market orientation increases the level of support and cooperation from suppliers, lowers the purchasing costs, and increases profit margins. H4c: A high employee orientation leads to a more homogenous internal culture, and a higher employee loyalty, mutual trust and motivation. This in turn leads to a lower salary level, an easily governed organization, a higher degree of delegation, and positive customer effects. H4d: A higher media and public orientation increases the flow of up-to-date information from all events and constituencies that may have impact on the firm, increases the firm’s ability to influence all of its constituencies, and improves the firm’s image among all constituencies. H4e: A higher authorities orientation increases the intensity and the effect of the firm’s lobbying, and increases the labor union’s support of these efforts. Regulatory decisions may become more favorable, and market access and governmental subsidies may be improved. 110 Since the value generating ability of the firm depends on the total constituent orientation, it logically follows that each environmental link has its own unique contribution. The specific contributions hypothesized are based on functional theory and reported field research for each constituent relationship. In hypothesis 4a it is uncertain whether a downstream market orientation will lead to a more dominant market position (market share), lower the marketing costs or contribute to profits. Both the commodity characteristics of the product as well as the distribution monopoly may prevent such an effect. Methods The sampling frame: The Norwegian utility industry association EnFO provided an up-to-date list of all the 243 electric utilities in Norway with names and addresses of all key managers of holding companies and subsidiaries. The utilities vary in ownership. The central government owns the national main-line distribution utility and the largest power utility. Local governments own most of the integrated medium-sized and small distribution and power generating utilities. Local shareholders own some small local utilities. A few of the larger power producers are privately owned and are either listed on the stock exchange or are wholly owned subsidiaries of industry conglomerates. The preliminary data collection discovered that some of the utilities were owned by other utilities or by corporations owning several utilities. The sampling frame was reduced to 176 utilities. Of these 14 did not want to participate. Data collection: EnFO and the research team sent a joint letter explaining the purpose of the survey to all the CEOs, asking their participation and cooperation in naming the top middle managers responsible for each of the five constituency relationships to be investigated. After pre-testing the six questionnaires 162 sets were sent to the utilities that had responded to the first letter and were confirmed as being organizations with strategic independence from other utilities. With one round of reminders 567 questionnaires were returned, ranging from 84 lobbying managers to 105 marketing managers, averaging a 58% response rate. A few of these questionnaires were not 100% completed, and could not be used for analysis. Only 26 utilities returned all six questionnaires with complete answers. Measures: Each of the six questionnaires contained approximately 100 questions. Multiple questions with 7-point Likert scales were used for each main construct. The 30 questions for each of the five partial constituent orientation constructs were identical except for the names of the involved parties, and covered gathering, disseminating and responding to constituent information. Questions to the CEOs were drawn from the five partial orientations, but the other party was named constituents, stakeholders or industry participants. Antecedents, moderators and consequences were measured through sets of questions ranging from a few up to 18 items for some key antecedents to single items for a few moderators and results. The questions answered by the CEO, and kept after the Factor and Cronbach Alpha analyses were completed, are shown by construct in Appendix 1. The items and Cronbach Alpha values of the constructs for the other five respondents can be obtained from the author in Norwegian or in English translation. 111 Analytical techniques: Factor analysis was used to confirm which construct each question belonged to. In a few cases one or two items were moved to other constructs than originally intended. A few items did not have sufficient partial correlation with any of the constructs, and were removed from further analysis. A few less central antecedents, moderators and consequences ended up with different names and content than originally hypothesized. Constructs expected to be one-dimensional were checked out via Factor analysis. Cronbach Alpha analysis was used to test the reliability of the constructs. A few items that reduced construct reliability were removed. Ordinary Least Square multiple regression and multiple correlation analysis was used to test the relationships between the constructs. Presence of co-linearity was investigated throughout. Differences in mean values of antecedents and orientations between the 1994 sample of large Norwegian firms and the 1995 sample of utilities were t-tested. In 26 of the utilities all six of the managers had completed all of the questions, allowing an exploratory investigation of the antecedents and consequences of the firm’s leadership group constituent orientation. Otherwise the 92 CEOs’ answers were used to investigate the antecedents and consequences of a firm’s total constituent market orientation. Interrelations between consequence constructs associated with specific constituencies and between the return on assets and other consequences were investigated using simple correlation analysis for each pair of consequences. Findings Factor analysis showed that all six constituent orientation constructs are one-dimensional. This confirms and extends the hypothesis put forward by Kohli and Jaworski. The reliability of the six measurements is high with Cronbach Alphas ranging from .87 for the CEOs’ orientation to .94 for the PR managers’ orientation. Factor analysis was used to find onedimensional antecedents, moderators and consequences where possible in order to reduce the number of predictor and dependent variables in the regression analyses, and reduce the colinearity problem. Multi-item variables were checked for reliability using Cronbach Alpha analysis. If the reliability was too low, the single item variables were used in the regression analysis rather than the multi-item variables found in the factor analysis. As expected, the antecedents were all multi-item variables, and virtually identical in composition between the five functional managers, and with the CEO where he had answered the same set of questions. Virtually identical one-dimensional multi-item moderators were found for the CEO and the five functional managers regarding constituent turbulence and competitive intensity. Other moderators and consequences of a market orientation varied in composition and content between the six managers. Several single-item variables turned up. The findings in the regression analysis supported Hypothesis 1. The antecedents for overall constituent market orientation and the orientation towards each constituency are similar but not identical. Many, strong and consistently market oriented leadership signals, a high risk tolerance in the leadership group, a low internal conflict level, a high interdepartmental connectedness and a low degree of hierarchy correlated positively with both the total and the five partial constituent market orientations measured. A varied and other-directed 112 TABLE 1. Multiple Regression Result _______________________________________________________________________ Dependent Variable: Constituent Orientation Variable Interdepartmental harmony measured via PR manager Use of EnFO measured via lobbying manager Goals of authority relations measured via lobbying mgr. Top manager signals measured via Purchasing manager Interdepartmental conflict measured via Personnel manager R2 Adjusted R2 Fdf:19= 11.63 P= .0000 Overall model: Raw Coefficient .40 Standardized Coefficient .70 P-value .0000 -.23 -.34 .0075 -.23 -.36 .0077 .21 .27 .0477 .14 .22 .0723 .72 .68 personal background of the top leadership group influenced positively all the constituent market orientations, but the background of the CEO failed to have any effect. A low departmentalization led to a higher constituent market orientation except in the case of the employee orientation where there was no effect. Giving priority to the constituents in the firm’s value chain led to a higher total constituent market orientation, but did not influence any of the five partial constituent orientations. In the 26 utilities with complete observations for the CEO and all the five top functional managers a composite measure of the firm’s total constituent orientation was constructed as the sum of six orientations. All antecedents measured in the firm were regressed against this composite orientation index. The results are shown in Table 1. Interdepartmental harmony and connectedness had the highest impact. It was measured for all of the five top functional managers, and each showed a high correlation with the orientation variable. Due to co-linearity between the harmony measurements, only one measure could be used in the regression. The PR manager reported harmony had the highest predictive power, and was kept as a predictor variable. I found the same co-linearity between the five measurements of constituent relation goals, top manager signals and interdepartmental conflict. In each case the strongest predictor from the group of predictor variables was kept in the regression. The high co-linearity within predictor variable groups indicates a high interrater reliability of the measurements of antecedents. In the lobbying area one question measured the degree of indirect versus direct contact with a constituent. The use of EnFO rather than direct Government lobbying had a negative impact on the total constituent orientation. It is interesting to note that only the goals of the authority relations had a negative correlation with the composite orientation measurement. Goals for all other constituency relations had positive, but weaker correlations with the orientation measurement. 113 The findings supported Hypothesis 2. The commodity characteristic of their main product electric energy, and the historic monopoly and the current partial monopoly of the utilities did significantly influence the mean constituent orientation level compared to identical measures of firms belonging to a representative cross-section of Norwegian industries. The utilities had on average a significantly lower general constituent orientation. The downstream market orientation gap was particularly wide. The upstream market orientation gap was the second biggest and slightly larger than the overall constituent orientation gap. The employee market orientation gap was also negative and significant, but not very large. The authorities and the public and media market orientations were identical in the utilities and the rest of large Norwegian firms. The latter finding is somewhat surprising given the important local society role of the utilities. The only average authority orientation in this heavily regulated industry is due to the behavior of the publicly owned utilities, which prefer to leave the lobbying to their very strong industry association EnFO. Utilities scored on the average significantly higher on all antecedents to the constituent orientations compared to other large Norwegian firms. At the time of the investigation the newly deregulated utilities seem to pursue what Slater and Narver define as programmatic market orientation, and are in the process of implementing a better systemic market-back learning without having caught up with firms with a more competitive history. Hypothesis 3 was mainly supported by the findings. The total constituent orientation as measured by the CEOs’ responses and both of the organization-internal moderators of generic strategy chosen had significant predictive power on return on equity and total assets as well as total unit costs. The correlation with return on assets was significantly stronger than with the other two consequences. Avoiding the generic strategic position of “stuck-in-the-middle” strengthened the effect of the orientation on the consequences, as both a differentiation and a cost strategy had positive effects on all three economic outcomes. Surprisingly, external factors had no moderating effect on the consequences when using the CEO self-reported degree of a constituent market orientation. In 26 utilities with complete responses the total constituent orientation was measured as the sum of the five partial and the CEOs’ orientations. Multiple regression was run against return on total assets using the composite orientation measurement and a wide range of moderators as predictor variables. The results are shown in Table 2. Most notably, the internal moderators disappeared from the regression, while the external moderators of turbulence and competitive intensity entered. There was a high degree of co-linearity between the turbulence moderators. Only the turbulence in the lobbying environment was kept as the strongest moderator from the group. The lobbying environment was particularly turbulent for some of the utilities in the aftermath of the deregulation. In general, the higher the external turbulence, the greater the correlation between the orientation and the return on assets is. The co-linearity in the reported competitive intensity in the constituency markets was not very high, except between media and the up- and downstream markets. The media competition was kept as it had the strongest partial correlation with returns on assets. With moderators from the constituencies not directly involved in the primary value chain, the correlation between the composite market orientation and return on assets was significant and negative. If the up- and downstream competition and turbulence levels are used in 114 TABLE 2. Multiple Regression Results __________________________________________________________________________ Dependent variable: Return on Total Assets Variable Turbulence in the lobbying environment The union representative a competitor or a partner Sum of constituent orientations Competition in the media market Competition in the lobbying Environment R2 Adjusted R2 Fdf:19= 12.46 P= .0000 Overall model: Raw Standardized Coefficient Coefficient .97 .58 P-value .000 .51 .50 .000 -.14 .24 .29 -.63 .24 .24 .000 .054 .077 .75 .69 the regression instead, and the media, lobbying and union representative competition are removed, the composite constituent orientation has a weak but significant positive partial correlation with returns on total assets. This instability may be due to the low sample size in this part of the analysis. It can also be seen as an indication that turbulence in constituencies not close to the value core forces a constituent orientation that is not productive in terms of current returns on assets. It may well be that the utilities that were the most disrupted by the deregulation have the most problems with current returns. The findings supported the main expectation in Hypothesis 4, but not all the subhypotheses. The consequences of the market orientation for each of the constituencies differ from each other. Each consequence has a unique partial contribution towards the total value generating ability of the firm. This was confirmed through a paired correlation analysis between return on assets and other consequences where most correlations were significant and positive. In addition several other significant correlations between constituent-specific consequence were found: The PR manager reported result on public image was strongly and positively correlated with the marketing managers reported customer satisfaction and the utility’s ability to respond quickly to competitive moves. Marketing manager reported relation building intent among customers is positively correlated with the personnel manager reported employee salary differentiation. Marketing manager reported ability of sales personnel to discuss customer signals with other employees is positively correlated with personnel manager reported low employee turnover and high job satisfaction. The findings also gave support to most of the partial consequence hypotheses shown below. Market turbulence and competitive intensity are significant moderators on the consequences of all partial constituent market orientations as well as for consequences of the overall constituent orientation. However, the effect of the internal moderators of generic strategic 115 choice could not be tested due to the composition of the sample and the fact that only the CEO answered these questions for the utility. H4a: A high downstream market orientation leads to significantly higher customer loyalty and satisfaction and ability to respond quickly to competitive moves, but not to lower marketing costs, higher market shares or profit margins. The lack of economic and market power consequences are probably due to the commodity character of their main product. H4b: A high supplier market orientation significantly increases the level of support and cooperation from suppliers, lowers the purchasing costs, and increases profit margins. H4c: A high employee orientation leads to significantly less presence of sub-cultures, higher employee loyalty, mutual trust and motivation, a lower compensation level, a more easily governed organization, a higher degree of delegation, and positive downstream market effects. It also produces a more proactive culture. H4d: A higher media and publics orientation significantly improves the flow of up-to-date information from all events and constituencies that may have impact on the firm, the firm’s ability to influence all its constituencies, and the firm’s image among all constituencies. In addition it was found that a higher media market orientation has beneficial effects in the downstream markets. H4e: A higher authority orientation significantly increases the intensity and the effect of the firm’s lobbying, and the labor unions’ support of these efforts. It also lowers the conflict level with the government. However, the correlation with the regulatory decision outcomes was negative, and correlations with market access and governmental subsidies were insignificant. When analyzing the consequences separately for privately owned utilities the correlations with regulatory decision outcomes, and especially increased market access through grants of concession rights, became positive. Discussion Major findings A market orientation exists in an organization towards a series of internal and external constituencies. The market orientations can be defined and measured through identical onedimensional concepts with scales that can be directly compared and be combined to one common organizational double-loop learning scale. All measured general and partial constituent market orientations are influenced by external historic and situational factors. These factors influence all the firms in the utility industry in the same direction. The impact on each firm is moderated by organization-internal factors. Internal antecedents explain variations in constituent market orientations within the utility industry. Virtually identical antecedents of internal situation, 116 programmatic learning, organizational systems and architecture influence the overall and each of the partial constituent market orientations. All partial constituent orientations contribute in unique and interactive ways to the overall economic performance of the firm via consequences unique to each constituent. The correlation between the overall constituent market orientation and return on assets is strong and positive. The intensity of competition, the intensity of market change, and the opportunity to convert market knowledge to differentiation, (develop a unique selling proposition) consistently and strongly moderate the antecedents and consequences of a market orientation. This suggest that a market-driven knowledge management is particularly important and beneficial when conditions are changing in markets where the competition is based on unique value-added. Managerial implications Even though the business culture of all the utilities is negatively influenced by the lack of competition in the industry, there is considerable variation in the degree of market orientation between utilities. The leaders can significantly improve profitability by raising the overall constituent market orientation. The payoff from an increased constituent market orientation depends on the presence of market turbulence, competitive intensity and the ability to differentiate from competitors in each of the constituent markets. This suggests that the utilities should not primarily increase their market orientation downstream. The distribution utilities have a local monopoly, and do not benefit from increased learning about their customers, but can benefit from learning more about macroeconomic changes that influence the total market demand and supply and the commodity price. However, distribution utilities can enter new profitable business by using their network for carrying other services than supplying electric power. Since they would essentially differentiate the commodity product electricity by packaging it with a range of new services a downstream market orientation may become important if they expand their business domain. The power utilities find it very difficult to differentiate their product downstream in ways customers are permanently willing to pay for. To some extent they have succeeded in differentiating through close cooperation with very large customers, but not with small customers. The historic combining of distribution and power generating in one utility will probably be outlawed in Scandinavia in the near future, taking away the differentiation opportunities based on the distribution network. The power utilities have, on the other hand many opportunities to differentiate themselves in ways meaningful to all the other constituencies. They should do so, and coordinate and intensify their market-driven learning and marketing effort towards the labor market, the finance market, the upstream markets, the government, the media and the public. There is a lot to be gained, as the average degree of market orientation is particularly low in the industry because of its monopoly history. The leadership of the utility can materially increase the degree of constituent market orientation towards all constituents using the same set of values, goals, leadership style and reengineering of the firm’s task handling architecture and systems. They should do so, and make sure the process is combined with a strategic reorientation and a clear choice of 117 generic strategy that applies equally to all constituencies of the firm. The harmonization of key values in the firm is important for reducing the conflict level. Often conflicts start as moral ones, and are transmitted to task-related and personal conflicts. Conflicts cannot permanently be solved at any of these three levels without reducing the moral belief conflict, either through value based management, or by removing employees that have unacceptable morals. A common value based platform for all internal and external communication will be essential for succeeding with the cultural change management outlined above. The utility will have many employees doing part-time marketing towards the various constituencies. The job of the professional full-time marketing people should become one of coordinating the total corporate communication, and otherwise educate and coach all the part-time marketers within the firm. It becomes the job of every employee to contribute to the monitoring of changes in the environment, and to communicate this information to colleagues. The market-driven development of competency within the firm will increase if the organization reduces its use and size of hierarchy and increases the horizontal cooperation and coordination between activities along value chains within the firm and with the value chains of its constituencies. To do so the control system of the utility has to be built bottom-up starting with logistics, production and exchange activities. Self-control of delegated decision making authority becomes the most important. Second-most important will be insight into horizontal activities, i.e. a collegial control. This will provide to the individual insight into integration issues, which lessens the need for middle management, and secure double-loop learning across functions, professions, business units and departments. It is a top management responsibility to make sure such a control network is developed, but everybody must provide input and use the control system. The control information must be seen as an opportunity for learning, not as a system for administering rewards and penalties. Team organization with rotating membership of key constituents is particularly well suited for achieving the above. Research implications Market orientation must be studied in the future as a managed cultural change process that involves multiple-loop market-driven learning from all markets within and surrounding the firm. The marketing concept applies to all areas of exchange, not just the downstream market. This is important for understanding the effectiveness of marketing activities and the area of applying marketing. The unit of investigation is primarily the firm. The unit of investigation becomes complex when dealing with the orientation towards a single constituent. Efforts should be made to develop a generalized market exchange theory. A merging of marketing-, purchasing-, public relations-, lobbying-, personnel management- and financing theory should be both possible and beneficial in the understanding of both market orientation and how the firm manages and develops its constituent relationships, value creation and multimarket competition. The constituent market orientation process is complex. It involves all employees and key representatives from all constituencies. In corporations operating with several business 118 units it involves all of them as synergy is a result of concrete activity links between value chains and networks. Since the process is dynamic, involving both top-led programmatic learning and systems reengineering and market-back learning from the daily task-handling, dynamic research techniques should be used. In many cases the investigation of dynamic links have been difficult and prone to misinterpretation since a cross-sectional survey technique was employed in this study. The model currently identifies poorly endogenous and exogenous variables. The survey material indicates that consequences are antecedents to each other. The consequences should be antecedents to antecedents, moderators and the market orientation in the next time period. In several case studies of the dynamics of the early phases of the programmatic change process I have consistently found very large gaps between the market orientation level selfreported by top leaders, middle management, the front line, and the external constituents of that firm. The gaps are reduced as the market-back learning improves. For highly marketoriented firms it does not matter where the measurement is done within the firm or its main constituents. The constituent orientations as defined in this paper are just as applicable to governmental and other non-profit organizations. Market orientation assumes a minimum degree of freedom of choice for the parties. It does not require the existence of pure competition and unrestricted choice. Future investigations should include such organizations. Finally, a small technical note on the research presented in this paper. The sample was not large enough to use confirmatory factor analysis to test thoroughly the validity of the many new or modified measurement scales. APPENDIX A Translated questions The questions for the other constituents are available from the author in Norwegian and English organized by concept the items belong to. For each concept the Cronbach Alpha is shown. Antecedents to the CEO’s constituents orientation .77 Priority of constituents: Own employees Our union representatives Our owners and their board members Politicians and bureaucrats who influence our industry. Media and the general public Customers Suppliers 119 .64 Risk propensity I tell my employees that our survival depends on them being able to change with the market trends. I assume a free electricity market will be established in the Nordic countries. I must allow for possible higher prices in a Nordic market. .79 CEO signals I signal and inform about every step of our reorientation process I show the way and set the example for what I want in the change process. I communicate believable positive expectations for the change process I create a vision of how I want the organization to function in the future I meet changes with a positive attitude .59 Information channels for reorientation signals We inform about the reorientation process via the personnel management We inform about the reorientation process via the union representatives We inform about the reorientation process via our industry association We inform about the reorientation process via our PR manager We inform openly about the reorientation process via media .76 Information content in the reorientation signals Our senior managers personally exemplify what we want out of our reorientation process. Our firm signals trustworthy and positive expectations for the changes Our firm creates a vision of how we want our future organization to function. In our firm changes are met with positive attitudes. Our firm reacts immediately to changes among our constituents. .80 Marketing goals Sales growth is an important yardstick in our utility company. Changes in the number of customers are an important yardstick in our utility company. Changes in our market share are an important yardstick in our utility company. .69 Long-term goals Rentability of total assets is an important yardstick in our utility company. 120 Our utility is engaged in developing a sound economic and environmental utilization of the energy resources. Our utility continuously works for an economically safe and rational energy supply. .87 The CEO’s Constituents Orientation .75 Gathering information The executives are oriented about what happen within our constituencies. We regularly and systematically measure stakeholders' satisfaction with the cooperation with us. We have meetings with all of our stakeholders at least annually to map their concerns. We collect industry information through informal social meetings with friends in the industry and business partners. We regularly check to what extent we stay ahead of stakeholder needs. We are current with anything else occurring in our industry. .77 Spreading information internally Our salespeople regularly report on competitors' strategies. We have meetings across the departments at least quarterly to discuss results and developments within the stakeholder groups. Several departments meet regularly to discuss how to respond to our business environment. .78 Acting on the information We react quickly to changes in one or more of our constituencies. We require all managers to weight the fulfillment of their specific responsibilities against their contribution to the firm’s total results. We react immediately to changes in any of our stakeholder groups. We encourage our stakeholders to give us their ideas for improvements and change in our relationship. The activities of our departments are well coordinated Moderators to the consequences of the CEO’s constituents orientation Low-cost strategy 121 Cronbach alpha: 0.59 Measured as the factor 1 score of “Evaluate the importance of the following elements in your firm’s competitive strategy” (1= unimportant, 7= very important) Improve capacity utilization Modernize the production processes Frequent and detailed control reports Improve access to input factors. Differentiation strategy Cronbach alpha: 0.79 Measured as the factor 1 score of “Evaluate the importance of the following elements in your firm’s competitive strategy” (1= unimportant, 7= very important) Market segmentation Offer a broad product portfolio Conduct market investigations Promote the brand name(s) Offer differentiated products Consequences as seen by the CEO. Financial results Cronbach alpha: 0.73 Our return on assets compared to our competitors is... (7 point scale from much lower to much higher) Our total costs per unit compared to our competitors are..(7 point scale from much lower to much higher) Our return on equity compared to our competitors is... (7 point scale from much lower to much higher) References Aarhus, Vidar (1993), ”En studie av markedsorienteringen til norske fordelingsverk,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Allaire, Y. and M. Firsirotu (1984), "Theories of Organizational Culture," Organization Studies, 5, (3), pp. 193-226. Arndt, Johan (1985), "On Making Marketing Science More Scientific: Role of Orientations, Paradigms, Metaphors and Pussle Solving," Journal of Marketing, 47 (Summer), pp. 11-23. Bate, P. (1984), "The Impact of Organizational Culture on Approaches to Organizational Problem-Solving," Organizational Studies, 5, (1), pp. 43-66. Braae-Johannessen, Olav (1995), ”Den Norske Kraftbransjen - markedsorientert overfor media og publikum?” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. 122 Cravens, D. W. and N. F. Piercy (1995), “The Network Paradigm and the Marketing Organization: Developing A New Management Agenda.” European Journal of Marketing. Vol. 29 No 3, pp. 35-51. Cronbach, Lee J. and Associates (1981), Toward Reform in the Program Evaluation, San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass Inc., Publishers. Despandé, R., J. U. Farley and F. E. Webster Jr. (1993), ”Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness in Japanese Firms: A Quadrad Analysis,” Journal of Marketing, 57(1), pp. 23-37. Felton, A. P. (1959), "Making the Marketing Concept Work," Harvard Business Review, 37 (July-August), 55-65. Hagelund, Morten (1995), ”Leverandørorientering i kraftbransjen,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Harmon, F. G. & G. Jacobs (1985), The Vital Difference - unleashing the powers of sustained corporate success. New York: Amacom. Hunt, Shelby D. (1990), "Truth in Marketing Theory and Research," Journal of Marketing, 54 (July), 1-15. Jaworski, Bernard J. & Kohli, Ajay K. (1993), Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences, Journal of Marketing, vol. 57, July. Kohli, Ajay K. & Jaworski, Bernard J. (1990), Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications, Journal of Marketing, vol. 54, April. Kotler, Philip (1988), Marketing Management, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Laksfoss, Cathrine (1996), ”Med strømførende omgivelser - en studie av interessent-orientering i kraftbransjen i Norge,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Levitt, Theodore (1960), "Marketing Myopia," Harvard Business Review, 38 (4), pp. 45-56. (1969), The Marketing Mode, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. (1980), "Marketing Success Through Differentiation of Anything," Harvard Business Review, 58 (January-February), pp. 83-91. McNamara, Carlton P. (1972), "The Present Status of the Marketing Concept," Journal of Marketing, 36 (January), pp. 50-57. Mitroff, I. I. (1975), Stakeholders of the Organizational Mind. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Narver, John C. and Stanley F. Slater (1990), "The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability, "Journal of Marketing, 54 (October), pp. 20-35. _____ , _____ and Brian Tietje (1998), ”Creating a Market Orientation,” Journal of Market Focused Management, 2, pp. 241-255. Nevett, T. and R. A. Fullerton (1984), Historical Perspectives in Marketing. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Nordby, Nina (1995), ”Personalorientering i kraftbransjen - en del av det utvidede markedsorienteringsbegrepet,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Olaussen, Kristin (1994), ”Personalorientering - en del av det utvidede MO-syn,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Olsen, Børge (1995), ”Myndighetsorientering i kraftbransjen,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Ormstad, Anne Karin (1995), ”Et utvidet markedsorienteringsbegrep - finnes en generell omgivelsesorientering?” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. 123 Payne, Adrian F. (1988), "Developing a Marketing-Oriented Organization," Business Horizons, (May-June), pp. 46-53. Peters, T. J. (1988), Kreativt Kaos. Oslo: Cappelen Forlag. and N. Austin (1985), A Passion for Excellence. New York: Random House and R. H. Waterman (1982), In Search of Excellence. Cambridge, MA: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. Ruekert, Robert W. (1993), "Developing a market orientation: An organizational strategy perspective," International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8, 3 (August), pp. 225-45. Salicath, Karianne (1993), ”Leverandørorientering - en del av et utvidet markedsorienteringsbegrep,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Schein, H. E. (1985), Organisasjonskultur og Ledelse: Er kulturendring mulig? Oslo: Mercuri Forlag. Selnes, Fred , A. K. Kohli and B. J. Jaworski (1992), "Market Orientation: A Comparison of the United States, Denmark, Norway and Sweden," NIM Working Paper Series 92-04, Sandvika: Norwegian School of Management. Shapiro, Benson P. (1988), ”What the Hell is ”Market Oriented”?” Harvard Business Review, November/December. Sheth, J. N., Gardner, D,. M. and D. E. Garrett (1988), Marketing Theory: Evolution and Evaluation. New York: Wiley. Sivertsen, Astrid Marie (1995), ”Å kartlegge den eksisterende kultur hos produsentene og distributørene innen elektrisitetsbransjen i Norge, som et grunnlag for en vurdering av deres situasjon, og hvor de står i sin markedsorientering,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Slater, S. F. and J. C. Narver (1995), ”Market Orientation and the Learning Organization,” Journal of Marketing, 59(3), pp. 63-74. Sverdrupsen, Geir Ole (1996), ”Kraftbransjen - Markedsorinetert eller ikke?” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Tellefsen, Brynjulf (1995), Market Orientation, Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget A/S. Thingbøe, Per Morten (1995), ”Markedsorientering i kraftbransjen – Kundeorientering,” Masters thesis, Oslo, Norway: The Norwegian School of Management, School of Marketing. Tunstall, W. Brooke (1986), "The Breakup of the Bell System: A Case Study in Cultural Transformation,", California Management Review, 28 (Winter), pp. 110-24. Webster, Frederick E., Jr. (1988), "Rediscovering the Marketing Concept," Business Horizons, 31 (May-June), pp. 29-39. (1992), "The Changing Role of marketing in the Corporation," Journal of Marketing, 56, (October), pp. 1-17. 124