Marcia Salner's Full Report (Word document)

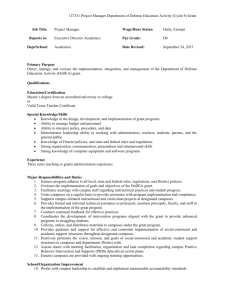

advertisement