Fall 2010 Outline

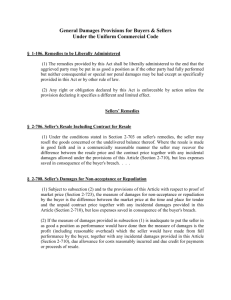

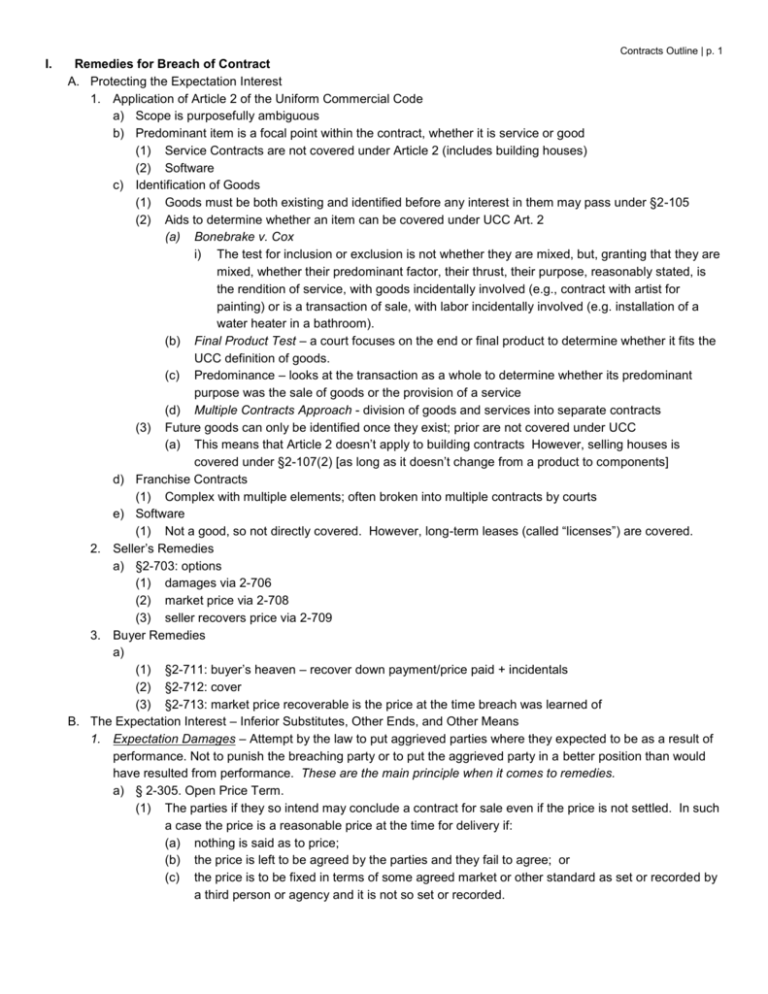

advertisement