Newman Book Review

advertisement

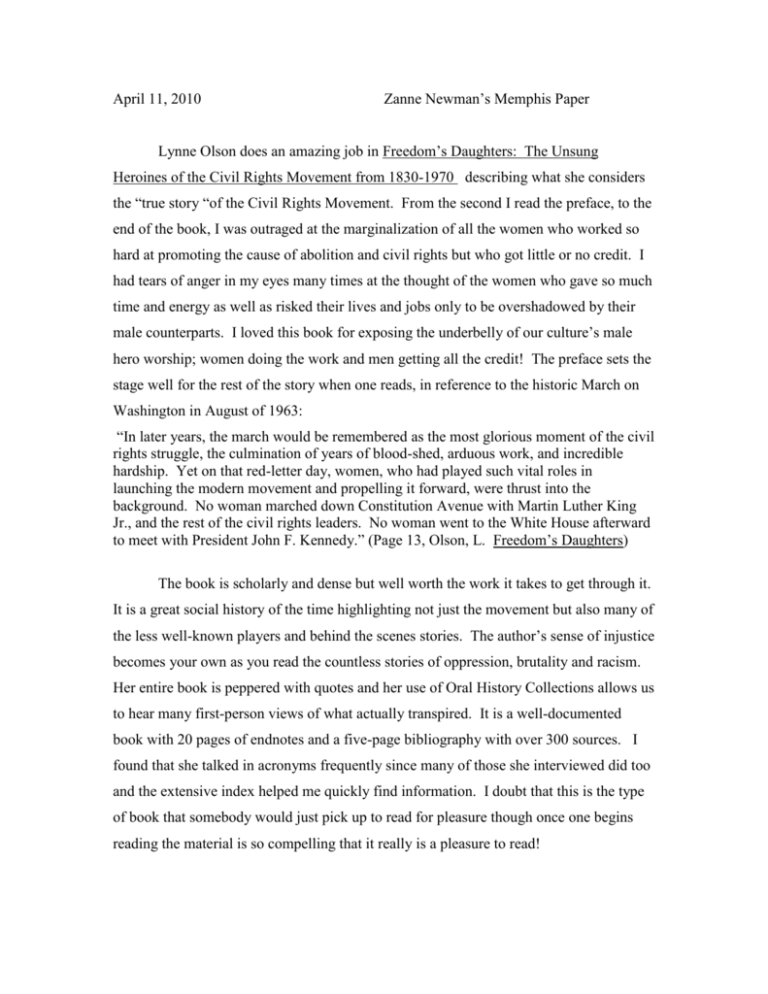

April 11, 2010 Zanne Newman’s Memphis Paper Lynne Olson does an amazing job in Freedom’s Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830-1970 describing what she considers the “true story “of the Civil Rights Movement. From the second I read the preface, to the end of the book, I was outraged at the marginalization of all the women who worked so hard at promoting the cause of abolition and civil rights but who got little or no credit. I had tears of anger in my eyes many times at the thought of the women who gave so much time and energy as well as risked their lives and jobs only to be overshadowed by their male counterparts. I loved this book for exposing the underbelly of our culture’s male hero worship; women doing the work and men getting all the credit! The preface sets the stage well for the rest of the story when one reads, in reference to the historic March on Washington in August of 1963: “In later years, the march would be remembered as the most glorious moment of the civil rights struggle, the culmination of years of blood-shed, arduous work, and incredible hardship. Yet on that red-letter day, women, who had played such vital roles in launching the modern movement and propelling it forward, were thrust into the background. No woman marched down Constitution Avenue with Martin Luther King Jr., and the rest of the civil rights leaders. No woman went to the White House afterward to meet with President John F. Kennedy.” (Page 13, Olson, L. Freedom’s Daughters) The book is scholarly and dense but well worth the work it takes to get through it. It is a great social history of the time highlighting not just the movement but also many of the less well-known players and behind the scenes stories. The author’s sense of injustice becomes your own as you read the countless stories of oppression, brutality and racism. Her entire book is peppered with quotes and her use of Oral History Collections allows us to hear many first-person views of what actually transpired. It is a well-documented book with 20 pages of endnotes and a five-page bibliography with over 300 sources. I found that she talked in acronyms frequently since many of those she interviewed did too and the extensive index helped me quickly find information. I doubt that this is the type of book that somebody would just pick up to read for pleasure though once one begins reading the material is so compelling that it really is a pleasure to read! The book is a chronologically organized and the reader gets a great sense of many of the lesser known events that foreshadowed similar famous civil rights events. One such example is Pauli Miller’s ( a Howard University law student) leadership of a silent sit-in demonstration at Thompson’s cafeteria in Washington D.C. in 1944. It was a group organized and led solely by women and pre-dated the famous Woolworth sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, which was carried out by men. I found myself fascinated by all the earlier events led by women that I had never heard of in any of my reading about the civil rights movement. Additionally, I was astounded to read about the important contributions of so many women who never gained great fame for their part of the movement. Everybody knows who Rosa Parks is but few have heard of Jo Ann Robinson and Mary Fair Burks and the Women’s Political Council. Jo Ann Robinson and Mary Burks were professors at the all-black Alabama State College and were the president and founder respectively of the council. Both these women had been victims of Montgomery’s racism and both were energized to do something about it. According to Olson, in 1950 it was Jo Ann Robinson, then the new president of the WPC, who started to work on the problem of abuse of blacks on city buses. (Olson, L. p.91) They worked closely with the city’s two leading male black activists, Rufus Lewis and E.D. Nixon, the president of the local chapter of the NAACP. Robinson continued to approach the mayor about this issue and even threatened that there would be boycott as early as May of 1954. This was easier said than done since so many blacks were afraid of the reprisals from whites and the potential to lose their jobs. The culminating change took place when a 15 year-old girl, Claudette Colvin was arrested for violating the state segregation laws and resisting arrest. They put her in jail which shocked and outraged Montgomery’s black community. Finally there was a face for a test court case until it was discovered that Colvin was pregnant. The wheels were set in motion to raise money for this case and to get a boycott ready in 1955. According to Olson, “the black women of Montgomery were ready to explode.” (Olson, page 95) Rosa Parks worked for the NAACP in Montgomery and became the test case for a bus boycott when she wouldn’t give up a seat to a white woman in December of 1955. Like a lot of this book, this story is all about all that went into the planning of this event long before the famous moment when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat and what happened afterward. The author’s background as a journalist helps the stories come out as good bits of investigative reporting. The details of who did what, when and how unfold clearly with evidence for all her reporting. She lets us see the hard work that this bus boycott was for so many domestic workers (women) who had to walk long distances to get to work without the buses. Some are reported to have walked as far as 12 miles (page 117) to go apply for work. I have studied this event many times and was unaware of so many of the famous women that were responsible for the boycott’s success. Like so much of this period, women were the foot soldiers of the battle. “The relationship between male and female leaders of the Montgomery bus boycott would set a pattern that would continue into the civil rights movements of the 1960s: Women would operate behind the scenes, acting as organizers, strategists, fund-raisers and foot soldiers, while the men would be in the public eye, dealing with the white power structure and the press.” (Page 125) I found myself outraged when Martin Luther King, Jr., not the women and men who worked so hard and gave up so much for this boycott, gained all the media attention and national prominence. The women who actually suffered and struggled through this boycott were rarely mentioned. As the book progresses and the civil rights movement heats up, the author spends a lot of time describing the feuds between various groups and how, though many of the workers were female, the men increasingly were the figure heads and made all the decisions. I think the author makes a great case for how short-changed women were during this struggle when she tells the stories of these women’s lives and the risks that they would take to keep the movement going. Girls and local women would join the movement when SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) workers would come to town. The older women were role models for those around them. “Those women stood up to the system….they talked back and in the process, taught me how to be a stronger woman.” (Page 204) I had no idea that many of these women took these risks. They felt that though that it was dangerous for them, “many said that they were on the front lines because it was too dangerous for the men to be there, that men would be killed for doing what they were doing.”(204) Their heroics encouraged, and in many cases got the male workers enthusiastic enough to re-join the struggle. In this long, 400 plus page book, the story that upset me most was that of Septima Clark, a woman who Olson clearly shows is essential to the civil rights movement all over the South. She drove the voter registration campaign by the development of the citizenship schools where she created materials and practices to teach basic literacy to black voters so that they could understand politics and read well enough to register to vote. She came up with a program to train teachers to train more adult students. “It was like a chain letter, blacks form all over the South being taught that they had the power to change their lives and then going back home and passing the word along.”(214) Eventually, her program was put under the auspices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) headed by King. She was upset by the waste in the movement and what she saw as so many men who were in the spotlight but not doing the “unglamorous work of actually organizing the people.” She played a VERY important role in the movement and was ultimately responsible for so many new black registered voters. By 1970 over one hundred thousand blacks were taught to read and write by the citizenship school teachers (over ten thousand strong) that she and her colleagues had trained. (page 223) Even so, she had very little voice when it came to suggestions to the SCLC leaders. She knew that her suggestions were ignored. “Those men didn’t have any faith in women, none whatsoever,” Clark said. “They just thought that women were sex symbols and had no contributions to make. Whenever I had anything to say, I would put up my hand and say it. But I did know that they weren’t paying attention.”(page 222) I was angry and frustrated to discover that she worked so hard for so long but was so disillusioned at the end because of the movement’s sexism. She single-handedly created citizenship schools, one of the most important contributions to the civil rights movement, but got very little credit for all that she did because she was a woman. Lynne Olson’s book is an ode to the many women whose sweat and hard work were the backbone of this incredible movement in our history. The stories the Olson tells of the sheer bravery and energy of these women makes for a great read, but more importantly a wonderful historical lesson. Her carefully researched work feels balanced and accurate but is never dull or dry. I “met” so many wonderful colorful figures through this book and I would HIGHLY recommend it to others who are interested in learning more about some “unsung heroines” themselves. Because this book has a more journalistic rather than strictly historical feel it would appeal to a greater audience than most historical works. It is immensely readable without feeling trite or embellished. Those with a great knowledge of this period would benefit from learning about some of the smaller “characters” who were part of America’s drama. Readers who want a great overview of the period would do well to do some background reading first since so much of this work is about the groups that drove the movement rather than the movement itself. Though the index is good, if one does not know about all the groups and major events of the civil rights movement, this book would be a bit fractionalized and confusing. It would be a great book to read in tandem with an historical explanation of the period.