Imperialism

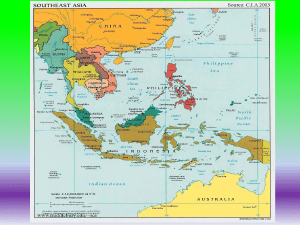

advertisement

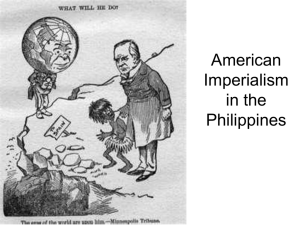

Imperialism The United States Takes Up the White Man’s Burden ". . . to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them," – W. McKinley MALEVOLENT ASSIMILATION In 1999, Joseph Ileto, a Filipino American postal worker was gunned down in a Los Angeles suburb by an admitted white supremacist. Racial violence in contemporary America is usually not as deadly, but nonetheless perpetuated in both explicit and subtle ways. Like other peoples of color, Filipinos have faced cross burnings in their front yards, been denied service at restaurants, limited in their upward mobility at workplaces, and rendered invisible as a community. These experiences and the fifty-year struggle for equity by Filipino veterans of WWII are indicative of a racist sensibility that was developed over a century of subjugating a people to American imperialist demands. The beginnings of that subjugation are artfully portrayed in our centerpiece picture. President McKinley holds the brush of education, as he is about to bathe a black Filipino child in the waters of civilization. The Filipino, however, with spear tightly in hand, resists McKinley's attempt at "ethnic cleansing." By the time this political cartoon was published by Judge magazine in June 1899, Spain had already sold the Philippines to the US for $20 million under the terms of the 1899 Treaty of Paris, and the Spanish American War was officially over. Symbolized in this cartoon of the black Filipino's refusal to be "bathed" is the Philippine's resistance to American colonial rule. A year before this cartoon was published; the Philippines was declared an independent nation by the revolutionary forces under General Emilio Aguinaldo. Most of the country had already been liberated from Spanish rule when the United States imposed its expansionist agenda on the new republic. The Philippine Revolution was thus forced to continue its pursuit for national independence in the Philippine American War. What to the United States was only an "insurgency" required the deployment of 126,000 US troops, and took the lives of anywhere from 250,000 to a million people, the vast majority Filipino. Although the Philippine American War was officially declared to have ended in 1902, fighting continued well beyond the first decade of the century. The "Filipino's First Bath" - in their own blood - was America's baptism as an imperialist colonial power in the Pacific. In this rite of passage, the United States deployed two armies - soldiers and teachers - to quell resistance and instill in the Filipino a "captive mind." A fierce national debate ensued in this country between pro- and anti-imperialists that became the subject of political campaigns and media editorials. In most publications, as represented in the samples in this exhibit, Filipinos were presented to the American public as dark skinned savages. These portrayals were intended to project Filipinos and non-whites in general, as inferior beings within the racialized milieu of US society. Filipinos were portrayed as diminutive (slaves) (pickanninies) or wild beasts - images that were associated with blackness. These depictions were intended to vilify Filipinos as the enemy much like Japanese, Vietnamese, and Arab peoples were demonized during the most recent wars. What Americans saw in pictures was reinforced by a racist language that labeled Filipinos as "gugus", "niggers", and "monkey," and by the promotional hard sell of world fairs, such as the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, that displayed Filipinos along with other native peoples from other countries as uncivilized beings. By the 1920's, the collective mind of the general public was established in its belief in the subservient status of the Filipino. Thus, the first large group of Filipino immigrants into the United States was confronted with institutionalized racism that prohibited marriage with whites, barred residence in white neighborhoods, and ultimately restricted immigration from the Philippines. Meanwhile, the United States set up a colonial arrangement with the help of Filipino elites that allowed US corporations unlimited access to Philippine natural resources such as timber and minerals, and control of major industries. They created a market in the islands for American surplus products, installed the largest military bases outside the US, and exploited Filipinos as a pool of cheap labor for US businesses and the military. Note the mass migration of contract workers recruited to work in the fields of Hawaii and California in the 1920's and '30's, and the mass recruitment of Filipinos in the US and the Philippines into the American military during WWII. Over the past 100 years, like the black Filipino child who resisted McKinley's bath, Filipinos have continuously fought back against all forms of injustices. Among the Filipinos in the US, this was evident in the manong generation that fought for decent wages in the 1920's and decent housing in the 1970's in struggles like the I-Hotel. It was evident in the aftermath of Joseph Ileto's death as his family and community activists spoke out against hate violence. And it is evident today among the Filipino veterans struggling for equity, among students supporting affirmative action, and among young activists demanding the toxics cleanup of former US bases in the Philippines. These are the legacies of the "Filipino's first bath" in waters of civilization that were evidently polluted with racism. We chose the month of June for this exhibit because of its historical significance for both African Americans and Filipinos. On June 19, 1865, slaves in Texas learned of their emancipation; and on June 12, 1898, Filipinos declared their independence from Spain. Our separate histories are filled with many stories of struggles for justice. Now and then, the stories converge as it did in the Philippine American War when David Fagin and other African American soldiers joined the Filipino revolutionary forces to protect a fledgling republic from US domination. Their example foreshadowed the kind of inter-racial cooperation that became necessary for future generations to forge in the resistance against racism. MANIFEST DESTINY A popular concept since the U.S.-Mexican War ear in the mid-1840's, "manifest destiny" was the belief that the white race was divinely ordained to spread westward to the Pacific shores, bringing government, economic prosperity, and Christianity to the continent. Fueled by the successes of industrialization, the United States pursued an aggressive policy of expansion through territorial purchase, land grants, homesteads, and military campaigns. By the late 1890's, the desire of big business for foreign markets and sources of raw materials whetted the appetite for territorial expansion overseas. With the demise of the Spanish empire came the opportunity to acquire colonies abroad, fulfilling American industry's craving for new sources of wealth through the creation of a global empire. Expansionist sentiment was further aroused by commercial rivalry with other imperialist powers. The pro-imperialists saw the United States as the inheritor of the "white man's burden." As one cartoonists expressed it: "There was once an old 'Yank' who lives in a shoe/covered all over with red, white, and blue/His family is large and still growing bigger/The result of good work in snapping the trigger." CONQUEST AND COMMERCE The war with Spain in 1898, highlighted by Commodore George Dewey's dramatic defeat of the Spanish armada at Manila Bay on May 1, was the road to American overseas expansion and conquest. Initially, many believed that the Spanish-American War was to help Cubans free themselves from Spanish rule. On December 10, 1898, the U.S. forced a defeated Spain to transfer control of Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines to the United States through the Treaty of Paris. Around that time, the U.S. also added Hawaii and Samoa among its colonial possessions. The United States had joined the ranks of imperialist powers such as England, Germany, and France in carving up the globe. While many Americans led by the anti-expansionists opposed the colonial conquest of the Philippines, others argued that expansion was necessary for commerce and the capture of foreign markets for U.S. surplus products. Senator Albert Beveridge's speech in Congress in 1900 was a rallying cry for U.S. imperialism: "The Philippines are ours forever.... And just beyond the Philippines are China's illimitable markets.... Our largest trade henceforth must be with Asia. The Pacific is our ocean.... The Philippines gives us a base at the door of all the East." Pointing to a map on his wall, President William McKinley declared: "I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States ... and there they will stay...." EDUCATE, CIVILIZE AND CHRISTIANIZE THEM On June 12, 1898, the Philippine flag was first unfurled as Philippine independence was proclaimed before thousands of victorious Filipinos. By November, the Philippine Constitution was ratified, creating an executive branch, a representative assembly, and judiciary. Then came the election of a president and the dispatching of diplomatic representatives around the world. The creation of the first republic in Southeast Asia was cut short in February 1899 by the Philippine-American War. When President William McKinley told a delegation of church leaders that God had counseled him to annex the Philippines and "to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them," few Americans knew that the Philippines had an educational system older than that of the United States and that the majority of Filipinos were Catholic. McKinley's depiction of Filipinos as uncivilized pagans played on prevalent racist sentiments and served to justify an unpopular war. One commonly held view ranked peoples of the world into four grades of culture -- savagery, barbarism, civilization, and enlightenment. In this hierarchy, white America was the pinnacle of enlightenment while Filipinos belonged to the two lowest levels of culture and therefore incapable of self-government. Senator Albert Beveridge in a famous Senate speech referred to Filipinos as "a barbarous race" of children incapable of even understanding "Anglo-Saxon self-government" adding: "[God] has marked the American people as his chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit..." The first American teachers introduced English into hundreds of schools already in existence at that time but the myth that the U.S. brought the school to the Philippines remains to this day. American education became a tool for pacification and assimilation into the U.S. colonial system. "SPARE THE ROD AND SPOIL THE 'FILIPINO' CHILD" The McKinley administration aggressively promoted the idea that Filipinos were children incapable of governing themselves, thus justifying US annexation of the Philippines. Filipino resistance to U.S. sovereignty and the imposition of American democratic institutions were proof of their childish folly. There were many examples of political cartoons featuring Filipinos being spanked with the shoe of the "US Army" or beaten with the rod of "benevolent assimilation." One cartoon has "childlike" Aguinaldo caught between the rod of proimperialist Senator Albert Beveridge, and a candy from the anti-imperialist Senator George Hoar. President Theodore Roosevelt thought Filipinos needed a good beating so they would become "good Injuns." General Arthur MacArthur, head of the US forces in the Philippines from 1900 to1901 and father of Douglas MacArthur, exclaimed that Filipinos needed "bayonet treatment for at least a decade." KILLING NIGGERS AND RABBITS The letters and diaries of U.S. soldiers who fought in the Philippine-American War reflected the racist views fostered by mainstream media. Pvt. Humbleton of the Washington regiment wrote his brother: "Our fighting blood was up, and we all wanted to kill 'niggers.' This shooting human beings is a 'hot game' and beats rabbit hunting all to pieces." A.A. Barnes of the Third Artillery told his parents: "I am in my glory when I can sight my gun on some dark skin and pull the trigger." Filipinos were often called derogatory terms such as "niggers" and "gugus." The Philippine-American War took place at a time when segregation was being written into laws. A few years earlier, the Supreme Court approved the "separate but equal" doctrine in Plessy vs. Ferguson. The hopes for racial justice and equality under post-civil war reconstruction were dashed as African Americans were increasingly disenfranchised. Every week, two to three southern blacks were lynched -- tortured and hanged or burned before cheering white mobs. Many more were beaten in "nigger hunts." One saying went: "Kill a mule, buy another; kill a nigger, hire another." Southern writers depicted the African American as "a wild beast" and blacks were generally depicted in books, magazines, and popular advertisement as buffoons, subhuman, ignorant, and immoral. Six segregated regiments of African-American soldiers were sent to fight in the PhilippineAmerican War. While some felt that by demonstrating their loyalty they could improve the lot of African Americans back home; others grew increasing critical of the war. Sgt. John Galloway of the 24th Colored Infantry wrote: "The colored soldiers do not push [the Filipinos] off the streets, spit at them, call them damned 'niggers,' abuse them in all manner of ways, and connect race hatred with duty. The future of the Filipino, I fear, is that of the Negro in the south." Filipino revolutionaries were aware of racial injustice in the American south. One leaflet distributed by the guerrillas among the African-American soldiers mentioned the lynching of Sam Hose, a black farmhand lynched in Newton, Georgia. On April 23,1899, Hose was chained to a tree, mutilated, then burned in front of thousands of spectators; his remains were cut up and sold as souvenirs. Many African American soldiers became sympathetic to the Filipino cause and about a dozen changed sides and fought on the side of Filipino forces against U.S. colonialism. One, David Fagin, was promoted to captain in the Philippine revolutionary army. THE AUNTIES ARE COMING The Philippine-American War took center stage during the 1900 presidential election. The Republican incumbent, William McKinley, ran as the candidate for overseas expansion and big business. His Democratic Party opponent, the populist politician and orator, William Jennings Bryan, ran on an anti-imperialist platform, opposing the war and advocating for Philippine independence. The anti-imperialist movement to protest the Philippine American War and Philippine annexation began in Massachusetts. On November 1898, the Anti-Imperialist League was founded in Boston, and spread across the country with major branches in New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Chicago, and other cities. Among the founders were suffragist and Nobel laureate Jane Addams, labor leader Samuel Gompers, former President Grover Cleveland, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, reformer Ida Wells Barnett, and Moorfield Storey, the first president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Sexist and racist attitudes of the time were reflected in the jingoist clamor against the antiimperialists. The media depicted the "aunties," a term the anti-imperialists were derisively called, as old women enamored with the "savage" Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo. Thus, to oppose the war signaled a lack of manhood. Among the anti-imperialists feminized were William Lloyd Garrison, son of a prominent abolitionist; Republican Senator Eugene Hale; former Massachusetts governor George Boutwell, a friend of Abraham Lincoln and first president of the Anti-Imperialist League; Charles Eliot, president of Harvard University; former senator and Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz; journalist Joseph Pulitzer; Louisiana Senator Donelson Caffery; E.L. Godkin, editor of The Nation; Missouri Senator George Vest; Alabama Senator John Morgan; and Congressman Burke Cockran. Ironically, some of the anti-expansionist included notorious racists such as Senator Benjamin Tillman. Their opposition to Philippine annexation was motivated by a desire to exclude nonwhite immigrants to the United States, thereby preserving white racial purity. The leading anti-imperialist and Massachusetts Senator George Hoar was among the most vilified. In one cartoon he was portrayed as a black man which was intended as an insult. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens), America's preeminent writer and most famous anti-imperialist, was pictured as a savage. Twain spoke passionately against the annexation of the Philippines and was Vice-President of the Anti-Imperialist League from 1901 until his death in 1910. "We do not intend to free but to subjugate the people of the Philippines," he wrote. "I am opposed to have the eagle put its talons on any land." HAYOP A number of cartoonists drew Filipinos as various members of the animal kingdom: dogs, snakes, frogs, mosquitoes, elephant, flies, and more. Artists made conscious choices to depict Filipinos in trivialized or dehumanized form. Underlying the animal depictions, however, was a historical truth of Filipino resistance to American imperialism: people fighting to protect their territory against captivity, as would any being, animal or otherwise. Compared to portrayals of the imperial powers like America's Uncle Sam or Britain's John Bull, who were drawn in human form, Filipinos and their struggle were made unequal in political stature. Opposing this view were a few artists who humanized the Filipino in editorial cartoons that exposed the uncivilized brutality of imperialism. OTHER NATIVE PEOPLES Pro-imperialist media made no distinctions between the disparate cultures and ethnicities that became subjects of the American empire. In their eyes, "our islands and their people" of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, and the Philippines were the same as Africans, Native Americans and Eskimos: uncivilized pagans, savages, and heathens. Some cartoonists were aware of the fate awaiting native peoples of the Pacific Islands. Through the image of a Native American, Filipinos were warned, "Be good, or you will be dead." In fact, many of the officers and soldiers who fought in the Philippine American War, like Generals Adna Chaffee and Jacob Smith, were veterans of the Indian Wars. "We had been taught that the Filipinos were savages no better than our Indians," wrote one soldier. Ironically, General Henry Lawton, who helped capture Chief Geronimo of the Apaches, was killed in 1899 by Filipino troops under the command of Filipino General Lucerio Geronimo. EMILIO AGUINALDO: A VILLAIN FOR ALL SEASONS Emilio Aguinaldo, a leader of the revolutionary Katipunan against Spanish rule and later the first president of the Philippine republic, became the recipient of the American cartoonists' wrath. In the face of superior American firepower, Aguinaldo turned to guerrilla warfare, introducing the United States to a form of armed conflict that it would face again in Vietnam. Dozens of editorial cartoons vilified and demonized Aguinaldo for leading the Philippine armed resistance against U.S. rule. He eluded capture until March 1901 when General Frederick Funston masterminded his arrest by subterfuge. Aguinaldo formally surrendered, swore allegiance to the United States, and urged his followers to do the same. A year after his arrest, the US declared the Philippine American War to be over. But Filipinos continued to fight well into the next decade. Aguinaldo died in 1964. US WAR AGAINST THE PEOPLES OF MINDANAO The Philippine American War is historically associated with the conflict between the US and the Christianized Filipinos of Luzon and the Visayas. The United States, however, also fought in a second front against the Moro people in Mindanao and Sulu Archipelago. Like their brothers and sisters to the north, the Moro peoples were drawn by American cartoonists in a stereotyped manner. Our sampling of cartoon depictions run the gamut from bloodthirsty, "running amuck" savages to immoral polygamists. The lone Judge cartoon in this section shows a valiant American soldier enduring fire from the Moros and having to dodge the barbs of the anti-imperialist politicians unfairly criticizing their conduct on the battlefields of the Philippines. In fact, it was the Moros who risked death as they battled from their cottas or forts, which were the targets of U.S. rapid fire from rifles, Gatling guns (an early type of machine gun) and cannons. In the U.S., congressional investigations revealed many instances of atrocities and tortures committed by U.S. Army troops. GOVERNMENT BY CONSENT OR CONQUEST For at least three years from late 1898 to 1902, the United States' incursion into the Philippines was both the centerpiece of American foreign policy and the headlining subject of debate in the nation. President McKinley voiced the side of conquest: "Can we leave these people…to chaos after we have destroyed the only government they had?…(I)t is the duty of American government to provide them a better one…" Imperialism's highpowered advocates included the likes of then vice-president Theodore Roosevelt, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, and Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana. To them the conquest of the Philippines was the coming of age of American global power. Anti-imperialists on the other hand invoked the principle of "government by consent," not conquest. Lady Liberty became symbolic of a public opinion that simultaneously supported the Filipino cause for independence and criticized corporate globalization: "Do I represent the idea of popular government…or am I simply a trademark for goods of American trust manufacturers?" On this side of the debate were Senator William Jennings Bryan, Mark Twain, suffragist Susan B. Anthony and prominent African American leaders like the Reverend W. H. Scott and scholar-activist W.E.B. Dubois were among the national figures who challenged the official policy of American expansionism across the Pacific. FORBIDDEN BOOK To the victor goes the privilege of writing history, the glorification of its conquests, and the silencing of the conquered. The history of the Philippine American War is amassed in volumes of newspaper accounts, military reports, government documents, autobiographies, biographies, and letters by American soldiers. All, however, are part of a "forbidden book" buried in antique collections, libraries, archives, vaults, and private drawers. Forgetting was officially sanctioned so that a war that was at least 50 times more costly in human lives than the Spanish-American War, could be relegated in American textbooks as only an "insurgency." A few late 19th century journalists and political cartoonists, however, managed to express unpopular truths of massacres, tortures, pillaging, and wholesale destruction of villages. An anonymous editorial cynically read, "We may have burned certain villages, destroyed considerable property, and incidentally slaughtered a few thousand of their sons and brothers, husbands and fathers, etc., but what did they expect? ….And they complain that drunken American soldiers insult the native women. What did they expect from a drunken soldier anyway?" CARTOON IMAGES FROM PUCK, JUDGE AND LIFE Many of these cartoons were taken from the pages of Puck, Judge and Life magazines. These three were among the most influential opinion makers of their day. Puck and Judge employed color front cover and centerfold cartoons to opine on the issues of the day. Unlike Puck and Judge, Life did not use color in its cartoons. All three magazines employed some of the best artists of the day to draw for them. Puck and Judge were generally supportive of President McKinley. They wholeheartedly backed the U.S. war of conquest in the Philippines. In fact, at the time, Judge magazine was regarded as propaganda vehicle for the Republican party. Life magazine was one of the few published voices opposing U.S. imperial designs on the Philippines. Its cartoonists drew cartoons extremely critical of the war and many were supportive of the Filipino's aims of independence and freedom. The history of the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) is largely forgotten today in the Philippines and the United States. Forgetting was officially sanctioned; volumes of newspaper accounts, military reports, government documents, autobiographies, biographies and letters by American soldiers all became part of a "forbidden book" - so that a war that was at least 50 times more costly in human lives than the Spanish-American War was relegated in American textbooks as only an "insurgency." A few late 19th century journalists and political cartoonists, however, managed to express unpopular truths of massacres, tortures, pillaging, and wholesale destruction of villages. An anonymous editorial cynically read, "We may have burned certain villages, destroyed considerable property, and incidentally slaughtered a few thousand of their sons and brothers, husbands and fathers, etc., but what did they expect? ….And they complain that drunken American soldiers insult the native women. What did they expect from a drunken soldier anyway?" In 1898, the Philippine Constitution was ratified, creating an executive branch, a representative assembly, and judiciary. Then came the election of a president and the dispatching of diplomatic representatives around the world. But the creation of the first republic in Southeast Asia was cut short by the United States when it imposed its imperialist demands on the new republic. The Philippine Revolution was thus forced to continue its pursuit for national independence in the Philippine-American War. The Philippine-American War was also to become America's baptism as an imperialist colonial power in the Pacific, and this expansionist agenda was met with fierce resistance by Filipino Revolutionaries. When President William McKinley told a delegation of church leaders that God had counseled him to annex the Philippines and "to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them," few Americans knew that the Philippines had an educational system older than that of the United States and that the majority of Filipinos were Catholic. McKinley's depiction of Filipinos as uncivilized pagans played on prevalent racist sentiments and served to justify an unpopular war. One commonly held view ranked peoples of the world into four grades of culture -- savagery, barbarism, civilization, and enlightenment. In this hierarchy, white America was the pinnacle of enlightenment while Filipinos belonged to the two lowest levels of culture and therefore incapable of self-government. Senator Albert Beveridge in a famous Senate speech referred to Filipinos as "a barbarous race" of children incapable of even understanding "Anglo-Saxon self-government" adding: "[God] has marked the American people as his chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit..." The first American teachers introduced English into hundreds of schools already in existence at that time but the myth that the U.S. brought the school to the Philippines remains to this day. American education became a tool for pacification and assimilation into the U.S. colonial system. What to the United States was only an "insurgency" required the deployment of 126,000 U.S. troops, and took the lives of anywhere from 250,000 to a million people, the vast majority Filipino. Although the Philippine-American War was officially declared to have ended in 1902, fighting continued well beyond the first decade of the century. A fierce national debate ensued in the U.S. between pro- and anti-imperialists that became the subject of political campaigns and media editorials. In most publications Filipinos were presented to the American public as dark skinned savages. These portrayals were intended to project Filipinos and non-whites in general, as inferior beings within the racialized milieu of U.S. society. The imperialist cartoons appeared on the pages of Puck, Judge and Life magazines. These three were among the most influential opinion makers of their day. All three magazines employed some of the best artists of the day to draw for them. Puck and Judge were generally supportive of President McKinley. They wholeheartedly backed the U.S. war of conquest in the Philippines. In fact, at the time, Judge magazine was regarded as propaganda vehicle for the Republican party. In these cartoons, Filipinos were portrayed as diminutive (slaves) (pickanninies) or wild beasts images that were associated with blackness. These depictions were intended to vilify Filipinos as the enemy - much like Japanese, Vietnamese, and Arab peoples were demonized during the most recent wars. What Americans saw in pictures was reinforced by a racist language that labeled Filipinos as "gugus", "niggers", and "monkey," and by the promotional hard sell of world fairs, such as the 1904 St. Louis World Fair, that displayed Filipinos along with other native peoples from other countries as uncivilized beings. Meanwhile, the United States set up a colonial arrangement with the help of Filipino elites that allowed US corporations unlimited access to Philippine natural resources such as timber and minerals, and control of major industries. They created a market in the islands for American surplus products, installed the largest military bases outside the US, and exploited Filipinos as a pool of cheap labor for US businesses and the military. Note the mass migration of contract workers recruited to work in the fields of Hawaii and California in the 1920's and '30's, and the mass recruitment of Filipinos in the US and the Philippines into the American military during WWII. While many Americans led by the anti-expansionists opposed the colonial conquest of the Philippines, others argued that expansion was necessary for commerce and the capture of foreign markets for U.S. surplus products. Senator Albert Beveridge's speech in Congress in 1900 was a rallying cry for U.S. imperialism: "The Philippines are ours forever.... And just beyond the Philippines are China's illimitable markets.... Our largest trade henceforth must be with Asia. The Pacific is our ocean.... The Philippines gives us a base at the door of all the East." Pointing to a map on his wall, President William McKinley declared: "I sent for the chief engineer of the War Department and I told him to put the Philippines on the map of the United States ... and there they will stay...." On June 19, 1865, slaves in Texas learned of their emancipation; and on June 12, 1898, Filipinos declared their independence from Spain. Our separate histories are filled with many stories of struggles for justice. Now and then, the stories converge as it did in the Philippine American War when David Fagin and other African American soldiers joined the Filipino revolutionary forces to protect a fledgling republic from US domination. Their example foreshadowed the kind of inter-racial cooperation that became necessary for future generations to forge in the resistance against racism. Over the past 100 years Filipinos have continuously fought back against all forms of injustices. This document was modified from an original website which may be found at: http://digitalmedia.upd.edu.ph/digiteer/yankee/ Digiteer - Art Technology Culture by Fatima Lasay Contact fats@up.edu.ph Copyright © 2003 Fatima Lasay "Sangandaan 2003", an international conference on arts and media in Philippine-American relations, presents Filipino and Filipino-Americans the unique challenge and opportunity to assess, in reflective hindsight, how the events of the past century changed their lives. The "COLORED: Black and White" exhibition in the US is part of this commemoration together with ten contemporary Filipino artists in a new exhibition entitled "Yankee Doodles." In the virtual absence of discussions on the history of the Philippine-American War, "Yankee Doodles" responds by remembering and interrogating this critical period in American and Philippine history, and its consequences and implications in today's world.