Case Study: Selling Neiman Marcus

advertisement

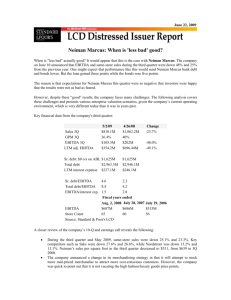

WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 Harvard Negotiation Law Review Winter 2007 Note CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS Bryce Klempner, Dharini Mathur, Lerato Molefe, Jen Reynolds, Tony Uccellini d1 Copyright (c) 2007 Harvard Negotiation Law Review; Bryce Klempner; Dharini Mathur; Lerato Molefe; Jen Reynolds; Tony Uccellini On May 2, 2005, the Neiman Marcus Group (“Neiman”) announced that it had accepted an acquisition proposal by a corporate vehicle controlled jointly by two large private equity firms, Texas Pacific Group and Warburg Pincus (“TPG/Warburg”). At the time of the sale, Neiman was the “crown jewel” of the luxury industry:1 the company’s stock was trading at an all-time peak; its management team was widely admired; and its financial health was excellent, with investment-grade credit and little debt.2 It was an expensive time to purchase such a high-quality asset; indeed, with a final price tag of $5.1 billion, the leveraged buyout ended up commanding far more money than analysts in both the private equity and retail industries had expected.3 What is remarkable about this deal is not simply that the company obtained such a high final price - a price that many industry insiders believed to be at, if not above, the top of its value range - but *236 that it did so with a common value auction that employed tight controls and seller-friendly deal protections within a relatively compressed timeframe. In theory, all these factors should have pushed the price down, not up. Neiman chose to sell after the Smith family, the company’s controlling shareholders, decided to liquidate. 4 The Smiths were by no means desperate to sell, but they wanted to take advantage of the favorable market conditions for the retail and luxury sectors.5 To that end, Neiman developed a rigorously controlled sale and auction that took place over several months. During that time, Neiman closely managed the bidding process from start to finish - all the way from handpicking the initial invitations to pressuring prospective bidders into “clubs” of Neiman’s choosing. Even the agreement’s deal protections provisions which have traditionally served as safeguards for the buyer - tilted in Neiman’s favor: the deal’s sliding reverse breakup fee, for example, effectively prevented any last-minute buyer’s remorse. The Neiman Marcus case thus presents one very successful solution to a common negotiation puzzle: how can a motivated seller extract maximum value, on its own terms, in a short timeframe? An answer can be found through close examination of the auction mechanics, deal protections, and risk management utilized in the Neiman acquisition. The story of how Neiman Marcus was able to pull off this auctioneering feat is an instructive and compelling example of successful, sophisticated deal design and implementation. This case study first sketches the factual background and details of the deal. It then outlines the case’s central puzzle and considers other possible solutions and additional considerations within the context of negotiation dynamics and the modern private equity industry. The Neiman deal may be exceptional in many ways, but it nonetheless provides an interesting case study in managing complex auction dynamics in a seller’s market. *237 The Making of a Deal For the Smith family, Neiman Marcus represented a large portion of their dynastic wealth. The Smiths had initially invested in Neiman as friendly acquirors, or “white knights,” in 1984, and the company became part of the larger Smith family conglomerate. Due to a series of mergers and tax-free spin-offs subsequent to the investment, along with periods of bad market conditions, the family had had little opportunity to exit the investment completely on favorable terms. 6 However, © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 because a tax obstacle raised by a previous restructuring had just expired, 7 and because retail businesses were selling well, mid-2005 appeared a propitious time for the Smith family to sell the company - and they were therefore very eager to do so.8 Neiman’s board of directors started evaluating the company’s alternatives. Business was good, and accordingly the company was not desperate to sell. The other alternatives, however - namely, recapitalization or a strategic merger - were not attractive to the board because of the unique qualities of the Neiman brand and the controlling shareholder family. Recapitalization would have involved taking on significant debt, but the shareholders would not have been comfortable assuming such a debt load, and the company was unwilling to compromise its capital investment program or its corporate image. 9 A strategic merger might have been more appealing, but at the time the only possible partner was Saks Fifth Avenue, which was busy with other transactions and whose merger with Neiman would *238 have been likely to trigger Hart-Scott-Rodino review.10 Because retailers were in vogue among financial buyers and the luxury market was especially robust, selling the company to a financial buyer seemed like the best way to achieve the interests of the Smiths and other Neiman stakeholders. 11 In January 2005, Neiman hired Goldman Sachs to draw up a list of possible financial bidders for the company. 12 Although management was interested in exploring all strategic possibilities, they wanted to bring financial bidders into the process early, so that they could bring potential buyers up to speed on the property.13 Several private equity firms expressed preliminary interest in moving forward, and Neiman set up a series of informational meetings throughout the next few months. Neiman’s banker, Goldman Sachs, offered financing to the bidders (“stapled financing,” so called because the “pre-baked financing package is ‘stapled’ to the target company and sanctioned by the seller”14), which gave the bidders a common floor for negotiating their own third-party financing arrangements.15 *239 The preliminary discussions and due diligence period lasted from February until April. During this time, Goldman was also lining up the sale of Neiman’s private-label credit card unit, a significant but non-core asset.16 The auction of the credit card division proceeded alongside the auction for the rest of the company, so that part of Goldman’s updates to the Neiman bidders included the progress on the credit card sale. 17 The proceeds of the sale would flow directly to the winning bidder. 18 In March, Goldman arranged the bidders into bidding consortiums, commonly known as “clubs.”19 At the beginning of the process, Neiman asked the bidders to sign confidentiality agreements that precluded any club formation without Neiman’s consent.20 Without signing the confidentiality agreements, potential bidders would not be given access to Neiman’s confidential internal documents, essential to the due diligence of any financial buyer. The company was not averse to club formation, however; in fact, Neiman and Goldman knew from the beginning that no single private equity firm would be willing to risk as much of its own capital as would be necessary for the non-debt portion of the purchase price.21 To maximize the competitiveness of the auction, Neiman wanted to promote the formation of as many bidding clubs as possible, while also ensuring that each club had the resources to fund the equity portion of the deal. Neiman *240 and Goldman therefore decided to limit the club size to a maximum of two firms. After consultation with potential bidders as to their preferences and research on which firms had worked well together in the past, 22 Goldman assembled the following pairs: TPG/Warburg, the Blackstone Group and Thomas H. Lee Partners (“Blackstone/Lee”), Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and Bain Capital (“KKR/Bain”), and Apollo Management and Leonard Green (“Apollo/Green”). Only two of these clubs made it to the finish line: Apollo/Green dropped out before bidding commenced, and although KKR/Bain did bid, they were out of serious contention before the final round.23 As the auction neared, Neiman sent a draft merger agreement to each club and requested comments. Upon receiving the markups, Neiman decided which changes were acceptable and merged them into a master “homogenized contract,” containing certain non-negotiable terms, for all the bidders to use in the auction process. 24 This homogenized contract featured stringent deal protections and, notably, did not contain a “financing out,” a standard provision that enables buyers to walk away from the deal should the financing fall through. In late April, Neiman asked for bids from the clubs. TPG/Warburg’s bid of $100 per share was the highest, with Blackstone/Lee in second place and KKR/Bain a distant third. After a weekend of negotiation on some of the deal terms, Neiman announced that TPG/Warburg had won the auction with an offer of $5.1 billion. That summer, HSBC purchased the credit card concern for $640 million,25 and in November, Neiman’s shareholders approved the sale to the TPG/Warburg club. The Puzzle Several aspects of this deal make it especially striking that Neiman fetched such a high price. 26 First, Neiman was a well-managed, *241 high-performing company, so a financial buyer would be unable to extract much marginal value via governance improvements.27 To the extent that private equity firms add value to their portfolio companies through operational upgrades, the lack of any evident problems to fix could have made Neiman a less appealing investment. 28 © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 Moreover, the luxury market was so inflated at the time that buying Neiman would be expensive relative to its expected value, causing a decrease in the rate of return on the investment. Second, the absence of strategic buyers - retailers or others who might be able to recognize synergies with Neiman’s existing operations - meant that there was little private value potential in this sale. In basic auction theory, there are two types of value that can be recognized by bidders: common and private. Common value properties will command similar prices across buyers because their value is well defined and widely understood; commodities such as pork bellies, for example, are common value items. Private value properties will vary in value, because those buyers who perceive unique synergies or affinities - a fan of Impressionist art bidding on a Monet, for example - will make higher offers than those buyers who are less idiosyncratically interested.29 Strategic bidders typically recognize more private value than financial bidders will, because they can imagine how the new property will fit into their preexisting business infrastructure; financial bidders, with no “business” other than investment, usually cannot realize these kinds of synergies and are only interested in common value. In Neiman’s case, there were only non-strategic financial buyers,30 so any private value “premium” would not apply.31 *242 Third, as discussed above, due to the size of the deal it was inevitable that private equity funds would team up into clubs to raise the needed capital,32 thereby reducing the number of bidders and possibly depressing the size of final bids in the auction.33 Club deals have become increasingly common in large public transactions, and there is considerable interest in how well they can absorb the risks inherent in teaming up to tackle complex, long-term projects.34 The challenge of managing different time horizons, divergent institutional priorities, and disparate internal structures could, conceivably, make it difficult to recognize the full value of their joint investment. 35 Goldman’s decision to exercise control over the pairings would seem to invite such mismatches and organizational clashes. Fourth, key provisions of the merger agreement - the reverse breakup fee and the lack of a financing out - shifted deal risk to the buyers, even in areas traditionally the responsibility of the sellers. 36 Although some buyers view reverse breakup fees as essentially “options” on the deal,37 in this case, the reverse breakup fee was too onerous to permit such an interpretation. 38 Moreover, because *243 Goldman offered stapled financing to all the bidders from the beginning, the clubs knew that they would not be able to claim that they were unable to find sufficient backing. In spite of all this, Neiman sold itself at an above-average premium (34% above its share price at announcement of the sale process, and nine times its cash flow), defying speculation by competitors, analysts, and other bidders alike. 39 How did Neiman manage to achieve such a high price on its own terms and timeline, without any apparent concessions to the buyers? The Answer Neiman’s tight auction controls, seller-friendly deal protections, and short timeframe ultimately did not, as intuition or conventional wisdom might suggest, paint the company into a corner. On the contrary, these three elements actually enabled the company to harness pro-seller market trends and capture substantial value. First, Neiman’s firm control of the process allowed the company to regulate crucial deal dynamics - including who bid, with whom, and on what terms - while eliminating uncertainties that may have depressed the final price. Second, Neiman’s cutting-edge deal protections ensured that the deal would not fall through or be subject to retrading at the last moment. Third, Neiman was in the right place at the right time: good timing, intelligent market analysis, and just plain luck contributed to its success. Closer examination of the negotiation puzzle in the Neiman context, then, reveals unexpected synchronicities between puzzle and answer. For Neiman, the same factors that might theoretically have destroyed value - control, protection, and timing turned out to be the very reasons the company commanded such an impressive price. 1. Controlling the Process. From the beginning, Neiman’s advisors orchestrated every aspect of the auction. 40 In January, Neiman invited specific financial *244 bidders to the table to begin negotiations before announcing the sale process to the general market.41 This minimized the risk of information leaks and allowed the management team and its advisers to concentrate their efforts on the parties most likely to offer a premium bid. The subsequent public announcement 42 that Neiman was investigating “strategic alternatives” ensured that the process did not miss any interested buyers and that Neiman was fully in compliance with its Revlon duties, which require companies to seek the maximum value for stockholders in a sale of the company. Inviting the participants was the first step; the second was to make sure that they worked together well, but not too well © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 bidder collusion is always a concern in the auction context. Neiman’s bankers at Goldman directed the formation of bidding consortiums - “a series of forced marriages,” in the words of one participant43 - to ensure a competitive bidding process that resulted in higher bids.44 Pre-partnering certain bidders can forestall anti-competitive pairings in which bidders band together to eliminate competition (as in the March 2005 buyout of SunGard Data Systems 45), leading to a lower final price.46 Since the formation of bidding consortiums was a foregone conclusion given the size of this deal, the confidentiality agreements served to prevent bidders from voluntarily forming teams without consent. This allowed Neiman to ensure that the resulting teams were the right size (that is, precisely two private equity firms each) and would complement each other well.47 Another important element of Neiman’s control of process was its insistence that bidders work from a homogenized contract that left *245 little room for last-minute retrades, creative departures, or tradeoffs.48 The pre-negotiated homogenized contract, coupled with a short, two-day timeframe for final negotiations, helped prevent an eleventh-hour attempt by the winning bidders to renegotiate terms once they learned that they had prevailed in the auction.49 Moreover, Neiman’s arrangement of a separate and concurrent sale of its credit card business was a key tactical move. The credit card business was a valuable asset that could command a high price if sold to strategic buyers in the financial services industry, because synergies with their existing retail credit businesses promised to create significant private value.50 A financial buyer of Neiman’s entire business would likely divest the credit card division soon after a buyout to reduce transaction debt, and therefore, would discount its value due to the uncertainty of the price it would fetch in a sale. By orchestrating the concurrent sale of the credit card business, Neiman was able to ensure that the unit’s full fair market value would devolve to its shareholders, decreasing uncertainty for financial bidders and pushing up final offers for the company. 51 2. Protecting the Deal. To ensure that the deal would be consummated, Neiman included a variety of contractual protections to incentivize the parties. Before starting the auction process, the board installed “golden parachutes,” or lucrative severance agreements, for key management personnel, in an attempt to ensure that management was fully committed to completing the auction process. Having the golden parachutes in place reassured management that their jobs would be secure regardless of the outcome of the auction. Although golden parachutes are often viewed as an anti-takeover measure, in this case *246 they provided reassurance to both the company and its potential buyers that the management team - which was, after all, one of the company’s greatest strengths - would remain in place.52 In addition, Neiman’s lawyers negotiated unusual contractual clauses to safeguard the deal for the seller. Traditional leveraged buyout (“LBO”) deal protections tend to place the onus largely on the sellers, giving buyers a higher level of confidence that the sellers will not continue to look elsewhere for a higher price. In this case, however, the traditional deal protections were supplemented by uncommon terms that focused on the buyers’ commitments.53 Most notably, the deal featured a “two-tier” reverse breakup fee of unprecedented scale, which broke new ground by completely omitting a financing out provision that might enable the buyers to abandon the deal. 54 Generally, reverse breakup fees impose predetermined costs on the buyers should they decide not to follow through on their agreement to purchase the company. In Neiman’s case, the reverse breakup fee imposed on the winning bidders a penalty of $140.3 million (about 3% of the enterprise value of the sale) if the deal fell through because the financing did not materialize. This was only the second time such a fee had ever been imposed in the LBO of a public American company. 55 Neiman improved on the first use, however, by adding a second tier: the fee jumped to $500 million (almost 10% of enterprise value) if the deal did not close for reasons other than financing.56 This second tier was so punitive that it essentially forced *247 the winning bidders to abandon any notion that they might use the reverse breakup fee as a real option on the company. 57 Apart from giving comfort to the Neiman board that there would be no dramatic last-minute bust-up,58 the lack of a financing out also eliminated the natural temptation on the part of the winning bidder to ratchet down the final price by claiming difficulty in obtaining debt financing necessary to consummate the merger and threatening to invoke the financing out clause. 59 Instead, the buyers’ only notable out would be a tightly drafted material adverse change (“MAC”) clause - and the buyers were well aware that the threshold for adverse events to qualify as a MAC is extremely high in Delaware courts. 60 Why would bidders as sophisticated as TPG and Warburg agree to terms that seem so skewed towards the sellers? In their own words, they were “very comfortable with the process.”61 They negotiated MAC clauses with the banks providing debt financing that mirrored almost perfectly the MAC clause in the sales agreement, so they were “very confident that their banks would show up.”62 Second, Neiman was negotiating from a position of strength: it was a highly-respected company and there was significant interest in the auction. In short, TPG/Warburg really wanted the company and believed that they would be able to close the transaction, so they were willing to accept fairly restrictive deal protections. Finally, to mitigate the buyers’ financing risk, Neiman’s bankers at Goldman Sachs offered potential buyers “stapled financing” for the deal.63 This creates © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 for buyers a convenient negotiation floor vis-à-vis other potential *248 sources of leverage, because their financing is guaranteed.64 Moreover, stapled financing may enable buyers to bid more boldly by guaranteeing the availability of financing on certain terms. 3. Being in the Right Place at the Right Time. There are a number of intangible factors that facilitated this particular deal and may, in fact, have been unique to it. An equally motivated seller in a less auspicious context might not be as successful as Neiman, even if it followed the same formula. This deal arrived at a particularly opportune time in both the private equity65 and luxury retail industries.66 The depressed state of the US economy since the early 2000s and the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act made going private an attractive option for many public companies.67 As a company with an excellent management team and targeted marketing strategy, Neiman was reluctant to risk the breakup of the team and disruption of its long-term strategy. At the same time, private equity was booming, and funds were overflowing. 68 With a strong brand, well-defined retail concept, experienced management team, affluent customer base, and readily saleable consumer credit card business, Neiman was an ideal - if expensive - acquisition target. The luxury retail sector had proven itself one of the most resilient to economic shocks and industry fluctuations. It fell *249 together perfectly: investors were looking for opportunities, and Neiman was ready to sell.69 Fortunately for the company, market conditions remained favorable throughout the sale process. It also seems likely that the careful matchmaking among potential bidders added significant marginal advantage to those clubs that worked well together, while disadvantaging those that did not. A dysfunctional pairing could easily impair the process of raising large amounts of debt and preparing a strategy to realize returns over a number of years: disagreements could arise over a number of critical areas, including the balance of power, distribution of fees, investment time horizon, institutional competencies, and governance issues.70 That TPG and Warburg Pincus proved able to work together well was no doubt the result of careful pairing by Goldman Sachs - but, to a certain extent, it was also a stroke of luck. Another factor contributing to Neiman’s successful sale process was simply the quality of the company’s brand, management, and infrastructure. Neiman sold itself from a position of strength; had the company failed to get its reservation price, it simply would have walked away from the auction process. Similarly, had the company been less appealing, the buyers may not have acquiesced to as many of Neiman’s demands. Clearly, having something worthwhile to sell makes the sale much easier. Conclusion Controlling the process and protecting the deal were two strategies that played out particularly well in the Neiman deal. It is still too early to tell if some of the deal terms utilized in this transaction signal a trend in the industry. The reverse breakup fee and the diluted financing out have only been used in two other private equity deals in the United States - SunGard and Hertz - both of which *250 were, like Neiman, very attractive properties. For less attractive properties, it may be difficult for sellers to install these provisions without giving concessions in price or other provisions. Nonetheless, the Neiman Marcus acquisition is a compelling study in leveraging bargaining power, negotiating dynamics, and controlling auction outcomes. So how does a motivated seller extract maximum value, quickly? The answer is a combination of factors, including, most prominently, the ability to control the process and guarantee the deal’s completion. In the end, this negotiation was both atypical and successful - a sophisticated approach that met the needs of all the parties involved. Footnotes d1 Harvard Law School, J.D. expected 2007; Harvard Law School, LL.M. 2006; Harvard Law School and Fletcher Divinity School, J.D./MALD 2006; Harvard Law School, J.D. expected 2007; Harvard Law School, J.D. expected 2007; respectively. We thank our professor, Guhan Subramanian, for his advice and guidance throughout this project. 1 Bill Dreher & Caroline Costin, Crown Jewel for Potential Sale or Secondary (Deutsche Bank Company Bulletin), Mar. 16, 2006 at 3. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 2 See id.; see also Neiman Marcus Group, Proxy Statement (Form 14-A), at 18 (July 18, 2005) [hereinafter Proxy Statement]; Interview with Walter Salmon, Professor, Harvard Bus. Sch., in Cambridge, Mass. (Mar. 20, 2006) [hereinafter Salmon Interview]. 3 See, e.g., Dennis K. Berman et al., Neiman Marcus Nears $5 Billion Deal - Texas Pacific, Warburg Bid Trumps Rival Equity Firms; A Long Term Luxury Play, Wall St. J., May 2, 2005, at A3; Dennis K. Berman et al., Today’s Bids for Neiman Marcus May Be Dampened by Soft Market, Wall St. J., Apr. 29, 2006, at C4; Jonathan Birchall & James Politi, Neiman Marcus Sold for $5.1bn, Fin. Times, May 3, 2005, at 27 (noting criticism that “the deal was struck at the top of the market [and] the buyers might struggle to make money from their investment”); Nat Worden, Neiman Marcus Is Sold, TheStreet.com, May 2, 2005, http://www.thestreet.com/markets/natworden/10221095.html (quoting the chairman of a retail consulting and investment banking firm as saying that “it looks to me like [Neiman is] at the very top of the cycle, and that’s a bad time ... to buy the company”). 4 Although the family never publicly stated that they were interested in selling off their Neiman stake, industry insiders and analysts nonetheless speculated that the family wanted to move on. See, e.g., Dreher, supra note 1 (“We had been anticipating a secondary of the Smith family shares”); Deborah Weinswig, Charmaine Tang & Tina Hwang, NMGA: Evaluating Strategic Alternatives What Next?, (Citigroup/Smith Barney), Mar. 2, 2005, at 9 (“Richard Smith, 81, has been the center of industry discussion that he has been interested in monetizing this stake in Neiman Marcus.”). 5 Salmon Interview, supra note 2 (noting that the family’s decision to sell did not happen in a time-constrained “corridor or window” but rather at the “first opportunity”). 6 See Neiman Marcus Group, Inc., Preliminary Proxy Statement (Form 14A), at 11 (Jul. 8, 1999) [hereinafter 1999 Proxy], for the background to the 1999 Neiman spin-off from Harcourt General. 7 See id. at 10, describing the limitations that the tax-free distribution may impose on Neiman and the indemnity Neiman provided to Harcourt General for taxes that became payable by Harcourt General due to actions by Neiman Marcus. See also Bernard Wolfman & Diane M. Ring, Federal Income Taxation of Corporate Enterprise 584-85 (4th ed. 2005) (discussing the two- to five-year restrictive window created by §§ 355(d)-(e) for changes of control following a tax-free spin-off under § 355). After 2004, Neiman was beyond the long end of the restrictive window and therefore had very little risk of violating § 355 for the Harcourt General spin-off in a change of control. Robert Willens, Two-Class Stock Spinoffs Leave Vulnerable Castoffs, The Daily Deal, Nov. 23, 1999. Revenue Ruling 69-407 mentions the “permanent realignment of voting control” requirement of § 355, which means that the two classes of stock cannot be recombined for five years, making sale options more complicated. 8 Note that the clearing of the tax issues was, at most, a necessary condition to a sale, not a sufficient one. During 2000-03, the Smiths would likely not have been eager to sell even without the tax limitations, because the company’s stock price was depressed. 9 Salmon Interview, supra note 2. 10 Id. 11 Id. (observing that the “wind was at the back” of the luxury retail market in early 2005); see also, e.g., Tracie Rozhon, In a Shopping Frenzy: Investors, Flush with Cash, Go After Retail Chains, N.Y. Times, Apr. 14, 2005, at C2 (noting that “[t]he retailing industry [was] gripped by frenzy” to sell); Tracie Rozhon, To Cash in on Luxury, Think of Selling the Store, N.Y. Times, Feb. 9, 2005, at C1 (stating that Neiman Marcus would be, according to one expert, “a coveted but expensive prize ... for a financial trophy hunter”) (internal quotations omitted). © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 12 Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 20. 13 Id. Apart from Saks, LVMH and Nordstrom were also rumored to have an interest in a potential purchase, but none found the resources necessary to mount a serious bid. Neiman also wanted to be careful not to compromise its luxury retailer profile - not all of these potential strategic buyers had the right image. Salmon Interview, supra note 2. Moreover, Neiman was keen to minimize the possibility of information leaks and competitive risks of sharing information with competitors. See generally Ellen Byron, Neiman Marcus May Be up for Sale, Wall St. J., Mar. 17, 2005, at A3; Is Nordstrom Interested in Buying Neiman Marcus?: Seattle Company Is Mum on Speculation, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Mar. 17, 2005, available at http:// seattlepi.nwsource.com/business/216303_nieman17.html. 14 Successfully Managing Private Equity Conflicts of Interest, CapitalEyes (Bank of America), http:// www.bofabusinesscapital.com/resources/capeyes/a08-04-238.html (last visited Oct. 15, 2006). Stapled financing simply means that the bank advising the target company also arranges for the potential buyer’s financing. Therefore, the buyer, in theory, does not have to seek any additional financing to purchase the company - the target’s bankers have already “stapled” the necessary financing contracts to the purchase agreement. Buyers often use these contracts as a baseline or BATNA for negotiating with other third-party lending sources. 15 Telephone Interview with James Westra, Partner, Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP, in Boston, Mass. (Mar. 14, 2006) [hereinafter Westra Interview]. None of the bidders, including the winning bidders, used Goldman’s stapled financing. However, Goldman was part of the final financing arrangement. Neiman Marcus, Inc. Annual Report (Form 10-K), at 36 (Sept. 16, 2005). 16 The private-label credit card concern had $550 million in receivables. Andrew Ross Sorkin & Tracie Rozhon, Credit Card Business Draws Bidders to Neiman Marcus, N.Y. Times, Apr. 26, 2005, at C5; see also Tracie Rozhon, Neiman Marcus Deal Disappoints Investors Looking for a Second One, N.Y. Times, May 3, 2005, at C1. (stating that the credit card concern had been the subject of intense speculation, because Neiman shareholders were hoping to benefit from both the sale of the company and of the credit card business). 17 Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 21. 18 Rozhon, supra note 16 (quoting one executive as saying that the credit card sale would “serve as the down payment” on the Neiman purchase). 19 Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 22. 20 Telephone Interview with John Finley, Partner, Simpson, Thatcher & Bartlett, in New York, N.Y. (Apr. 3, 2006) [hereinafter Finley Interview]. 21 See James Westra, Club Deals, in PLI Corporate Law and Practice Course, Handbook Series No. 6063 (2005), available at WL 1517 PLI/Corp 261 (“When forming a club with a strategic partner, a private equity firm can obtain the benefit of the partner’s strategic knowledge of the industry or market and often access intellectual property of the strategic partner and the strategic partner’s good will in the marketplace.”) [hereinafter Club Deals]. In this particular case, it was clear to all parties that the bidding could approach or top $5 billion. If the equity sponsors had to pay 30% in a $5 billion deal, for example, this would require putting up about $1.5 billion, significantly more than even the largest private equity firms have shown themselves willing to risk on a single transaction. 22 Telephone Interview with Michael Carr, Managing Director, Goldman Sachs, in New Orleans, La. (Mar. 23, 2006). © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 23 James Politi, Neiman Board Weighs up Rival Buy-Out Offers, Fin. Times, May 2, 2005, at 17; see also Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 23. Neiman’s strategy of “pre-partnering” the clubs may have meant that there were “fewer people at the finish line” at the auction than there would have been if firms had chosen their own clubs. Westra Interview, supra note 15. 24 Westra Interview, supra note 15. Even with the homogenized contract, the bidders still made some small changes to the final version. Id. 25 Tracie Rozhon, HSBC to Acquire Neiman Credit Card Unit, N.Y. Times, June 9, 2005, at C4. 26 For price comparisons, see note 3, supra. 27 See Dennis K. Berman & Henny Sender, Private-Equity Players Turn to Bigger Prey - Lucrative Fees From Transactions Steer Buyout Firms to Big Deals; Tough Hunt for Valued Targets, Wall St. J., May 12, 2005, at C1; see also 1999 Proxy, supra note 6. 28 See, e.g., The Lex Column, Neiman Marcus, Fin. Times, May 3, 2005, at 20 (“Quite how the buyers ... plan to generate the typical private equity returns from this deal is unclear. It is certainly not a classic turnround [sic] story. Neiman is already in peak form.”) Note, however, that private equity firms are not looking solely for turnaround challenges, but seek growth opportunities as well. Westra Interview, supra note 15. A company like Neiman Marcus may offer many such opportunities in the short and long term. See generally Salmon Interview, supra note 2. 29 For a discussion of private and common value in auction theory, see R. Preston McAfee & John McMillan, Auctions and Bidding, 25 J. Econ. Lit. 699, 704-05 (1987). 30 See supra text accompanying notes 10-11. 31 Of course, the private equity firms could have their own version of a private value premium, depending on the varying competencies within the clubs. (Neiman has potential growth in, for example, home furnishings and junior lines; if a bidder had special access to retailing expertise in these markets, then it might have found some private value in this auction.) Moreover, if market analysts can be convinced to classify Neiman as a specialty store (rather than as a retailer), Neiman’s value will increase. Salmon Interview, supra note 2. 32 Telephone Interview with Douglas Braunstein, Managing Director & Head of Investment Banking Coverage, J.P. Morgan, in New York, N.Y. (Mar. 17, 2006) [hereinafter Braunstein Interview]; Finley Interview, supra note 20; Telephone Interview with David Leinwand, Partner, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, in New York City, N.Y. (Apr. 7, 2006) [hereinafter Leinwand Interview]. 33 Barbarians Knocking at Retail’s Gate, Financo Rev., Nov. 2005, at 3, available at http://www.financo.com/news/review/Financo_Review_-_November_ 2005.pdf. But see Club Deals, supra note 21, at 264 (noting that “some argue that clubs actually push up prices by making additional funds available”). 34 See, e.g., So Happy Together?, Corp. Control Alert, Nov. 2005, at 10 (observing that “[o]ther issues can emerge after closing as private equity players, accustomed to calling the shots ... must share power with other members of a buyout consortium”); David Stires, LBO Kings Go Clubbin’, Fortune, Apr. 3, 2006, at 29 (“And while clubbin’ is a relatively new phenomenon, the consensus [is] that this party is just getting started.”) 35 See Club Deals, supra note 21, at 268; see also Eileen Nugent, Global Overview: Join the Club, Expert Guides, 2005, available at © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 8 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 http:// www.expertguides.com/default.asp?Page=9&GuideID=135&Ed=43. 36 John L. Graham & Bradley C. Vaiana, Rolling the Dice, N.Y.L.J., Nov. 7, 2005, available at http://www.kslaw.com/library/pdf/rollingdice.pdf (discussing the recent seller-friendly trends of reverse breakup fees and no financing outs). 37 Some buyers think of reverse breakup fees as options on buying the company, because they provide a specified measure of damages, frequently capped at just a few percent of enterprise value, should the buyer decide against the deal. Westra Interview, supra note 15. 38 Finley Interview, supra note 20. 39 TPG/Warburg’s high yield bond financing for the Neiman acquisition did not materialize as planned, but the club was able to substitute bank debt. See Simona Covel & Tom Sullivan, Neiman Marcus Meets Skepticism: Long-Awaited Deal Sees Some Resistance as Market for Risky Debt Gets Jittery, Wall St. J., Sept. 29, 2005, at C4; Deal Notes, Corp. Control Alert, Nov. 2005, at 4 (commenting that the Neiman buyout, “[i]f anything, showed how liberal the bank debt market remains”). The substitution also included an asset-based revolving facility, bridge facilities, and senior secured notes in addition to the bank debt. 40 Finley Interview, supra note 20; Braunstein Interview, supra note 32. 41 See Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 20. 42 Press Release, Neiman Marcus Group, The Neiman Marcus Group Exploring Strategic Alternatives (Mar. 16, 2005), available at www.neimanmarcusgroup.com (follow “News and Events” hyperlink); Neiman Marcus Group, Current Report (Form 8-K), at 18 (Mar. 16, 2005). 43 Braunstein Interview, supra note 32. 44 Finley Interview, supra note 20. 45 See, e.g., Rob Assal, Consortium Bids: An Overview, Mondaq, Mar. 21, 2006, available at 2006 WLNR 4640314. Whether SunGard’s single-bidder situation reduced the final price is impossible to know, but the fear that a single consortium will undermine the auction process worries sellers in a variety of contexts. Compare the practice of tuangou (team purchase), which is gaining popularity with consumers and confounding retailers in China. James T. Areddy, Chinese Consumers Overwhelm Retailers with Team Tactics, Wall St. J., Feb. 28, 2006, at A1. 46 Braunstein Interview, supra note 32; Finley Interview, supra note 20. 47 Finley Interview, supra note 20. 48 Commenting on the homogenized contract, Robert Smith (of the Smith family) said that “John [Finley] did a great job handling the contract management process with each bidding party.” Carlyn Kolker, Dealmakers of the Year, Am. Lawyer, Mar. 2006, at 99, available at http:// www.stblaw.com/content/news/news554.pdf. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 9 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 49 As an example, consider a case in which there are three bidders, one of whom has bid $12 for an asset and two of whom have bid $10. If the leading bidder gets wind of the lower numbers - a likely occurrence, especially as losing bidders often justify their loss by suggesting that the winner has overpaid - then the leading bidder has an incentive to drop his bid to $11. These “retrades” often occur when too much time passes between the bids and the company’s subsequent pre-closing negotiations with the high bidder. Finley Interview, supra note 20. 50 See Sorkin & Rozhon, supra note 16. 51 Braunstein Interview, supra note 32. 52 Salmon Interview, supra note 2. 53 See generally Glenn D. West & R. Jay Tabor, Sungard and Neiman Marcus LBO Transactions - Increased Liability Risk to Private Equity Sponsors?, Private Equity Alert (Weil, Gotshal & Manges, LLP), June 2005, available at http://65.214.34.40/wgm/cwgmhomep.nsf/Files/PEAJun05/$file/PEAJun05.pdf. It is believed that these unusual terms were possible in this deal because Neiman knew it could set the terms. See Itai Maytal & Abigail Roberts, SunGard and Neiman Deals Debut New Reverse Breakup Fee, Others Could Follow - Analysis, Mergermarket, May 10, 2005, http://www.mergermarket.com/public/default.asp? pagename=editorial_detail&docid=668. 54 Typically, in deals involving financial buyers an investment vehicle is set up to consummate the acquisition. In this case TPG and Warburg formed Newton Acquisition Merger Sub, Inc., for the purpose of the acquisition. For sellers, the prospect of taking this asset-less “shell” to court should the deal go awry is not attractive. 55 The first use of such a fee was in the March 2005 leveraged buyout of SunGard Data Systems by a consortium of seven large PE firms. Assal, supra note 45. 56 See Proxy Statement, supra note 2, § 8.2; Finley Interview, supra note 20; Leinwand Interview, supra note 32. 57 Finley Interview, supra note 20. Whether the fee was too punitive (and therefore unenforceable) is not clear, since the deal went through. 58 See Graham & Vaiana, supra note 36. 59 Finley Interview, supra note 20. See, e.g., David J. Sorkin & Eric M. Swedenburg, Recent US Deals Depart from Traditional Financing, Int’l Fin. L. Rev., available at http://www.iflr.com/?Page=17&ISS=21163&SID=605652 (tracking the evolution of financing provisions in LBOs); Graham & Vaiana, supra note 36. 60 See, e.g., IBP, Inc. v. Tyson Foods, Inc., 789 A.2d 14 (Del. Ch. 2001) (detailing difficulty of invoking stringent MAC provisions). 61 Leinwand Interview, supra note 32. 62 Id. Because presumably the same adverse event would trigger both the merger MAC and the financing MAC, the buyers could be comfortable that they would never be in a situation in which one MAC was triggered but the other was not. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 10 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only CASE STUDY: SELLING NEIMAN MARCUS, 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 235 63 Proxy Statement, supra note 2, at 21. Note that such arrangements are not borne solely of the generosity of bankers - the fees generated by financing are significant. Braunstein Interview, supra note 32. 64 Westra Interview, supra note 15. 65 See Berman et al., supra note 3; see also Stanley B. Block, The Latest Movement to Going Private: An Empirical Study, 14 J. Applied Fin. 36 (2004); Emily Thornton, Going Private, Bus. Wk., Feb. 27, 2006, at 53 (discussing the influx of executives from public companies into private equity firms). 66 See Andrew Dolbeck, Shopping Spree: M&A in the Retail Sector, Wkly. Corp. Growth Rep., Apr. 25, 2005, at 1; KPMG, What’s Hot in M&A?: Consumer Markets, Dealogic M&A Rev. (Aug. 2005), available at http:// www.altassets.net/casefor/sectors/2006/nz8758.php; see also supra note 11; Glory Days: Private Equity, Economist, Aug. 6, 2005, at 58; Capitalism’s New Kings, Economist, Nov. 27, 2004, at 9. 67 See, e.g., Dimitry Herman, Why Are So Many Top Retailers and Consumer Product Companies Going Private?, Back Channel Media Newsl., May 24, 2005, available at http:// www.backchannelmedia.com/newsletter/story/2481102355/WHY_ARE_SO_MANY_TOP_ RETAILERS_.html; Michael Rudnick, Seeking Privacy: Some Public Home Furnishings Retailers Are Rushing to Take Advantage of Higher Valuations Offered by Private Equity Firms, HFN: The Wkly. Newspaper for Home Furnishings Network, Sept. 12, 2005, at 64; Angela Sormani, Retail is Back in Fashion, Eur. Venture Cap. J., Sept. 1, 2004, at 1 (reviewing European market). 68 See, e.g., supra note 11; see also Lauren Foster, FT Report: Business of Luxury, Fin. Times, May 18, 2005, at 3 (“Eager to cash in on the buoyant market for luxury merchandise, [private equity funds] are prowling round the industry looking for deals.”). 69 Choosing the right time to initiate a sale may be more than luck, but enjoying continued favorable market conditions throughout the auction process is undeniably lucky. See, e.g., Braunstein Interview, supra note 32 (observing that in the unpredictable environment of M&A practice, it can be “better [to be] lucky than good”); Salmon Interview, supra note 2. 70 Braunstein Interview, supra note 32; see also Andrew Ross Sorkin, The Great Global Buyout Bubble, N.Y. Times, Nov. 13, 2005, § 3 (warning that “if the debt market turns against [private equity players] - and it is bound to do so at some point - potential buyers or public investors may not be willing to pay the same prices”); Club Deals, supra note 21 (laying out governance considerations and risks for private equity consortiums); So Happy Together?, supra note 34, at 14 (“Some suspect that many club-backed companies saddled with an unwieldy decision-making apparatus won’t be nimble enough to dodge, or navigate through, a crisis when the inevitable downturn in the economy occurs.”). End of Document © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 11