From Nature's Time To Clock Time

advertisement

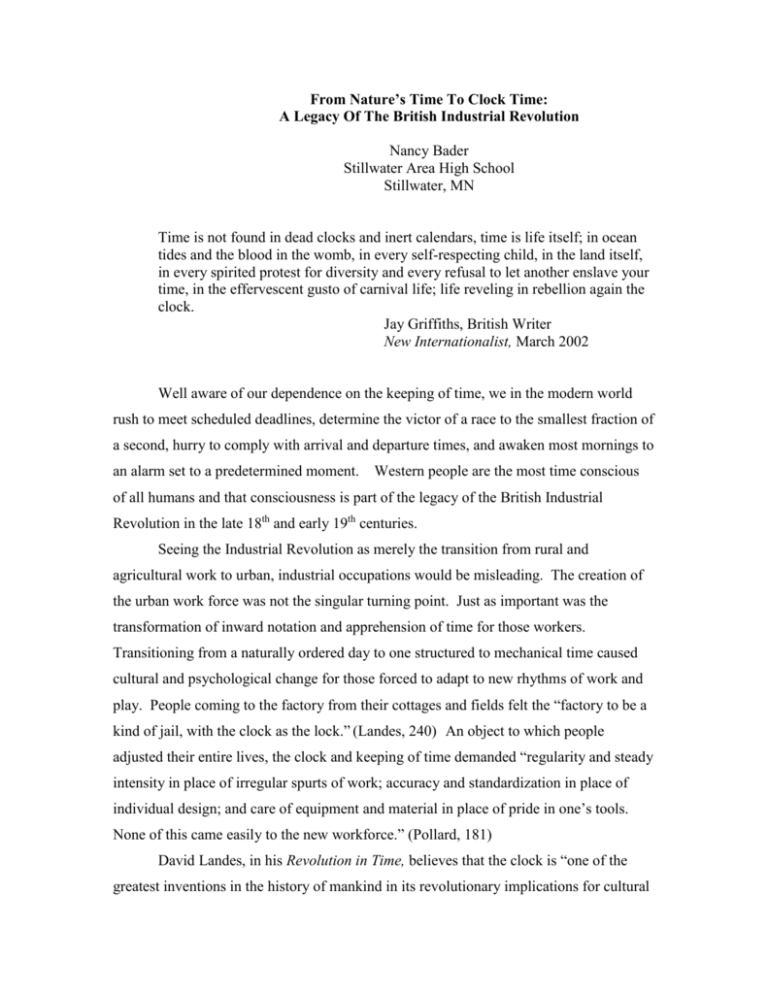

From Nature’s Time To Clock Time: A Legacy Of The British Industrial Revolution Nancy Bader Stillwater Area High School Stillwater, MN Time is not found in dead clocks and inert calendars, time is life itself; in ocean tides and the blood in the womb, in every self-respecting child, in the land itself, in every spirited protest for diversity and every refusal to let another enslave your time, in the effervescent gusto of carnival life; life reveling in rebellion again the clock. Jay Griffiths, British Writer New Internationalist, March 2002 Well aware of our dependence on the keeping of time, we in the modern world rush to meet scheduled deadlines, determine the victor of a race to the smallest fraction of a second, hurry to comply with arrival and departure times, and awaken most mornings to an alarm set to a predetermined moment. Western people are the most time conscious of all humans and that consciousness is part of the legacy of the British Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Seeing the Industrial Revolution as merely the transition from rural and agricultural work to urban, industrial occupations would be misleading. The creation of the urban work force was not the singular turning point. Just as important was the transformation of inward notation and apprehension of time for those workers. Transitioning from a naturally ordered day to one structured to mechanical time caused cultural and psychological change for those forced to adapt to new rhythms of work and play. People coming to the factory from their cottages and fields felt the “factory to be a kind of jail, with the clock as the lock.” (Landes, 240) An object to which people adjusted their entire lives, the clock and keeping of time demanded “regularity and steady intensity in place of irregular spurts of work; accuracy and standardization in place of individual design; and care of equipment and material in place of pride in one’s tools. None of this came easily to the new workforce.” (Pollard, 181) David Landes, in his Revolution in Time, believes that the clock is “one of the greatest inventions in the history of mankind in its revolutionary implications for cultural 2 values, technological change, social and political organization and personality.” Assessing those social and psychological implications for one, or any number of workers is an impossible task. It is possible, however, to examine the degree of change endured by workers as they transitioned from pre-industrial life to mechanized regularity of work that conflicted with tradition and one to which they were unaccustomed. That change robbed them of many of their customs and much of their freedom. In primitive peasant societies, organized in villages and dependent on agriculture as well as domestic industry, time has an occupational definition. In other words, time sense is task oriented and related to chores, primarily agricultural. Time follows natural rhythms and is determined by the logic of need. Crops are planted in springtime and gathered before weather interferes with the harvest, animals are put out to pasture in the morning and brought back in as night falls. Life follows the natural sequence of warm and cold, light and darkness, life and death. These natural rhythms make logical sense as we all, in our most basic level, live according to nature’s clock. These “circadian and circannual biological rhythms are stamped in our flesh and blood; they persist even when we are cut off from time cues; they mark us as earthlings” and are basic to our nature. (Landes, 13) Such was true for pre-industrial England. For the English cottage laborer or agricultural worker, there was personal control over the time, pace, and organization of their production. A laborer worked long hours, but they were his own set hours. With his wife and children working beside him, there was no alien power over his life determining the schedule for his day. Work was seen as a collective task of the family, a common responsibility with little demarcation between work and life, chores and recreation. If her house became stifling, she could slip into her garden. If his hands became sore from repeated motions, he could take time out to eat his lunch. The family unit was a collective group, dividing and completing tasks to ensure survival for all and work flowed naturally out of the passing of the day. A nostalgic, sweet view of preindustrial England doesn’t do justice to the hard work and precarious nature of the laboring family’s life, but for the worker, the perception was that it was a life of their own. (Hammond, 18) 3 According to Clifford Sharp, in his book “The Economics of Time”, humans have at their disposal “economic time.” That is, the time that a person allots between alternative activities. In all situations time is a scare resource; there are only 24 hours in a day, and the lives we live afford us a limited number of decades in which to participate in our world. Also, we can’t do more than perhaps one or two activities at a time so how we divide our time is an important personal decision and is a major factor in our personal happiness and satisfaction. With the development of industrial capitalism in England, and the growth of the factory system, the traditional nature based task orientation of time sense had to change and so did the locus of control over division of personal economic time. Specialization of manufacturing tasks and changes in production methods “demanded greater synchronization of labor and greater exactitude in time routines.” (Thompson, 80) Instead of the laborer determining the flow of his workday, a clock-dominated environment became predominant. His coming and going to work depended on the coming and going of others. Time allotted to a specific work task for the factory worker depended on the production rate of the other workers. The moving machinery and large labor force required a new time discipline and as time went on, the worker became “more encased by the time and tempo demands of his mechanized environment” and lost touch with the self-determination of pre-industrial life. (Thompson, 71) That selfdetermination was minimized even more as the distinction between their employer’s time and their “own” time became clear. With an uncompromising relentlessness, the clock and keeping of time channeled human energy toward work and immediate result, minimizing time for contemplative activity. The personal decisions that workers made pertaining to their “economic time” became limited and in most cases, extinct. The worker became part of an industrial way of life in which she was summoned by the factory bell, had her life arranged by factory hours, and lost her freedom to allocate time between labor and leisure as she wished. Either she “wholly submitted to the requirements of the employers and worked the day and hours prescribed by the mill owner, or she did not work.” (Mokyr, 90) As the clock hand ticked away, people became more and more attentive to the passage of time, to productivity, and performance. Workers, in effect, became “sellers of 4 time” and time became currency, thus necessitating employer assurance that time was not wasted. Time no longer “passed”, but was “spent.” The hand on the clock was a measure of time spent, used, wasted, and lost. As such “it was the prod and key to personal achievement and productivity” and during the 18th century, nowhere was demand for timepieces as large and growing as rapidly as in Britain. And since timekeeping is essentially an urban concern, no nation was so time-bound in its activity and consciousness as was Britain. (Landes, 238) Convincing the workers to conform to this new inward notation of time proved to be a difficult task. Not accustomed to a life dictated by the hands of a clock, workers unfamiliarity with such a system was most frequently displayed in their reluctance to arrive at work on time. Since workers didn’t spontaneously take to the new ways they had to be forced by work discipline and fines. (Hobsbawm, 64) Thus, a new system of discipline was developed to assure timeliness on the job. For the vast majority of workers who owned no timepiece, factory owners sent around “wakers” to tap on windows in the dark, early morning hours. Some workers had to rely on the bustle of urban life to determine the time. Elizabeth Bentley, a young factory worker testifying to the Committee on Factories Bill in 1832 stated “I generally get to work on time because my mother has been up at 4 o’clock in the morning; the colliers used to go to their work about 3 or 4 o’clock, and when she heard them stirring she has got up out of her warm bed, and gone out and asked them the time; and I have sometimes been at work at 2 o’clock in the morning when it is streaming down with rain, and we have to stay till the mill was opened.” For those late to work, serious fines were imposed to discourage tardiness. In the factories, pioneers like Richard Arkwright had the greatest difficulty “in training human beings to renounce their desultory habits of work, and identify themselves with the unvarying regularity of the complex automaton.” He “had to train his workpeople to a precision and assiduity altogether unknown before, against which their listless and restive habits rose in continued rebellion.” (Pollard, 183). Without machinery to set the pace in pottery manufacturing, Josiah Wedgwood instituted his own strict schedule of discipline. Those who came late to his factories “should be noticed, and if after repeated marks of disapprobation they do not come in due time, an account of the time they are deficient in 5 should be taken, and so much of their wages stopt as the time comes to if they work by wages, and if they work by the piece they should after frequent notice be sent back to breakfast-time.” (Thompson, 82). The fines imposed were generally much more considerable than the loss of time and such regulations were harsh for people unconditioned to a mechanized, regimented way of life. Such social change, for the workers, could only increase a sense of alienation and powerlessness within their new industrial world . “The machine cannot be challenged. It both creates and blots out, doing each with glacial impersonality. It measures people in the same way it measures money, and the growth of trees, the life span of the mosquitoes and morals, the advance of time. And when the hour strikes on the Big Clock, that is indeed the hour, the day, the correct time. When it says a man is right he is right, and when it finds him wrong he is through, with no appeal. It is deaf as it is blind.” (Fearing in Anderson, 58) This time-consciousness and attitude of time-thrift was enforced throughout society. Schools, for example, taught industry, frugality, order, and regularity while education was seen as “training” in the habits of industry. Religious tracts railed against idleness and taught that wasting time was a sin. Certainly such moral critiques were not new and unique to the Industrial Revolution. The difference was that now those who professed such beliefs were imposing their views on the working people. In A Christian Directory, R. Baxter professed that “a wise and well skilled Christian should bring his matters into such order, that every ordinary duty should know his place, and all should be…as the parts of a Clock or other Engine, which must be all conjunct, and each right placed.” Ironically, where once the pre-industrial family worked together as a collective group, industrial workers were again considered collective but in an all together difference sense. The analogy, in a time conscious mechanized world became one of people as parts of a machine working together, coming and going with perfect timing to maximize efficiency. It was not one of human interaction, relationship, decision making, and freedom. Wordsworth, in The Prelude, his poem on the growth of a poet’s consciousness, spoke out against such a view, railing against The Guides, the Wardens of our faculties, And Stewards of our labour, watchful men 6 And skilful in the usury of time, Sages, who in their prescience would controul All accidents, and to the very road Which they have fashion’d would confine us down, Like engines…… E. P. Thompson suggests that it is of little value to determine which way of life was the better one; the pre-industrial task-oriented time consciousness or the industrial time-discipline shift. He goes on to say that what historians can see is that the “historical record is not a simple one of neutral and inevitable technological change, but is also one of exploitation and of resistance to exploitation; and that values stand to be lost as well as gained. (Thompson, 94.) If asked to what degree the Industrial Revolution shift in mechanization and time-consciousness influenced the workers there can be only one answer. Profoundly. And as we check our own watches and hurry through our scheduled day we must recognize how the shift in time sense is still so prevalent in our own modern world as a legacy of the British Industrial Revolution. References Anderson, N. (1961). Work and Leisure. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Ashton, T. S. (1968). The Industrial Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bentley, E. (1832). Testimony To the Committee on Factories Bill. June 4, 1832, Entry lines 5206-5211, page 197. Hammond, J. L., & Hammond, B. (1917). The Town Labourer. England. Hobsbawm, E. (1999). Industry and Empire . New York: The New Press. Landes, D. S. (1983). Revolution in Time. London: Viking. Mokyr, J. (1999). The British Industrial Revolution. Boulder: Westview Press. Pollard, S. (1965). The Genesis of Modern Management. London: Edward Arnold Ltd. Sharp, C. (1981). The Economics of Time. New York: Halsted Press. Thomas, K. (1965) . Work and Leisure. Past and Present, 30, 50-66. Thompson, E. P. (1967). Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism. Past and Present, 38, 56-97.