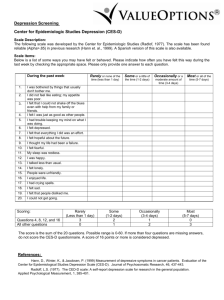

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

advertisement

Retrieved on June 12, 2009 from http://sakai.ohsu.edu/access/content/user/brodym/N574A%20Spring08/appendix/ Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) L. S. Radloff and B. Z. Locke Modified From: Rush J, et al: Psychiatric Measures, APA, Washington, DC, 2000. GOALS The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977) was developed to measure symptoms of depression in community populations. At the time of its development, researchers were interested in the health correlates of depressive symptoms and in tracking changes in severity of symptoms over time. The scale has also been used in many studies as a screen for the presence of depressive illness. Items were selected to represent the major components of depression on the basis of the clinical literature and factor analytic studies. Components include depressed mood, feelings of worthlessness, feelings of hopelessness, loss of appetite, poor concentration, and sleep disturbance. The scale does not include items for increased appetite or sleep, anhedonia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, guilt, or suicidal thoughts. DESCRIPTION The scale is a composite of 20 items selected mainly from the following sources: the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (Zung SDS), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Raskin Scale, a depression checklist developed by E. A. Gardner (unpublished manuscript, 1968), and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory Depression Scale (MMPI-D). Four of the items are worded in a positive direction to control for response bias. Subjects are asked to rate each item on a scale from 0 to 3 on the basis of “how often you have felt this way during the past week”: 0 = rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day), 1 = some or a little of the time (1–2 days), 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days), and 4 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). Sample items are provided in Example 24 –2. CES-D scores range from 0 to 60; higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. Total severity is calculated by reversing scores for items 4, 8, 12, and 16 (the items that control for response bias), then summing all of the scores. A score of 16 or higher was identified in early studies as identifying subjects with depressive illness. PRACTICAL ISSUES It takes approximately 5 minutes to complete the CES-D. The scale appears in several publications, including Weissman et al. (1977). The scale has been published in its entirety in Radloff (1977) and is available from National Institutes of Health Epidemiology Branch 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 The reliability and validity of the CES-D have been tested in African American, Asian American, French, Greek, Hispanic, Japanese, and Yugoslavian populations (Naughton and Wiklund 1993). The CES-D has been translated into several languages, including Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin), French, Greek, Japanese, and Spanish. PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES Reliability Internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha is high across a variety of populations (generally around 0.85 in community samples and 0.90 in psychiatric samples). Split-half reliability is also high, ranging from 0.77 to 0.92. Test-retest reliability studies ranging over 2–8 weeks show moderate correlations (r = 0.51–0.67), which is desirable for a test of symptoms that are expected to show change over time. Studies of African American versus Anglo-American versus Mexican American respondents showed no differences in measures of internal consistency reliability (Roberts 1980). Validity In samples of outpatients with depression, alcoholism, drug addiction, or schizophrenia, correlation coefficients (r) between CES-D scores and Symptom Checklist –90 (SCL-90) Depression subscale scores were high, ranging from 0.73 to 0.89. Correlations with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D) scores were variable and ranged from 0.49 for patients with acute depression to 0.85 for patients with schizophrenia. Correlations with the Raskin Scale were also variable, ranging from 0.28 for patients with acute depression to 0.79 for patients with schizophrenia (Weissman et al. 1977). Studies of elderly patients report only fair agreement between scores on the CES-D and the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Gerety et al. 1994) and a correlation (r) of 0.69 between the CES-D and the Zung SDS (DeForge and Sobal 1988). In a sample of 406 psychiatric outpatients, CES-D scores were higher in currently depressed patients than in other patient groups (Weissman et al. 1977). Mean CES-D scores for various patient groups were 38.10 for acute depression (n = 148 and SD = 9.01), 14.85 for depression in remission (n = 87 and SD = 10.06), 22.97 for alcohol dependence (n = 61 and SD = 13.58), 17.05 for drug dependence (n = 60 and SD = 10.69), and 12.98 for schizophrenia (n = 50 and SD = 12.94) In a primary care sample (N = 53), Fechner-Bates et al. (1994) reported that a chi-square test that compared DSM-IIIR categories of mild, moderate, and severe depression with and without psychotic features against CES-D scores above or below a cutoff score of 16 was not significant. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests for overall differences in severity of CES-D scores across the three DSM groups showed a significant difference between the mild and severe depression groups but not between moderate and mild or between moderate and severe groups. In a sample of 35 acutely depressed patients treated with medication, patients who were judged to be recovered by clinicians at the end of the study showed a mean decrease in CES-D scores of 20 points, whereas nonresponders or partial responders showed a decrease of 12 points (Weissman et al. 1977). In a study of the utility of the CES-D in discriminating depression in 406 psychiatric outpatients with a range of psychiatric diagnoses, Weissman et al. (1977) used a CES-D cutoff score of 16 to define case status. As expected, the CES-D showed a high sensitivity (99%) for acute primary depression and for depression in patients with alcohol dependence (94%) and schizophrenia (93%). Sensitivity was lower in patients with drug dependence (74%). Specificity, however, was low in patients whose depression had remitted (56%) and in those with drug dependence (59%) and somewhat higher in those with alcohol dependence (84%) and schizophrenia (86%). The authors concluded that the scale’s performance in differentiating primary depressions from those that occur in association with other disorders was less than optimal. In a community study of 720 subjects, Boyd et al. (1982) found that sensitivity for major depression as determined by Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) was low (64%) but specificity was high (94%) at a cutoff score of 16. However, the positive predictive value for major depressive disorder was only 33%. False-negative results were attributed to subjects who answered positively in the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) interview but negatively on the questionnaire. False-positive diagnoses were produced in subjects who showed CES-D symptoms associated with anxiety, drug abuse, phobias, panic, or somatization disorder. The results from a large follow-up study of 310 mothers of handicapped children are consistent with these findings. In examining the diagnoses obtained from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) of those who scored ³16 on the CES-D, Breslau (1985) found sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 73% for current major depression but also found that the sensitivity was 80% and the specificity was 73% when the target diagnosis was changed to generalized anxiety disorder. When subjects qualifying for both diagnoses were removed, sensitivity was 75% for major depression and 67% for generalized anxiety disorder. In 528 community subjects, Roberts and Vernon (1983) found that the CES-D yielded a false-positive rate of 16.6% and a false-negative rate of 40% for major depression as determined by RDC. The efficacy of the scale was not improved substantially when diagnosis was expanded to include minor depression or the depressive personality. Similarly, Myers and Weissman (1980) found a false-positive rate of 6.1% and a false-negative rate of 36.4% in a sample of 515 community respondents. Thus, the major community studies performed do not support the use of the CES-D alone as a screen for clinical depressions. In a sample of 425 primary medical care patients, Fechner-Bates et al. (1994) compared CES-D scores at or above 16 with DSM-III-R diagnoses obtained from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I). The CES-D was significantly related to a diagnosis of major depression but also to other Axis I diagnoses. For major depression, sensitivity was 79.5% and specificity was 71.1%. The positive predictive value was 27.9%. Adding subjects with bipolar disorder increased the positive predictive value to 31.3%. Of the subjects with elevated CES-D scores, 72.1% did not meet criteria for major depression, and a fifth of the depressed subjects scored below the CES-D cut point. The authors conclude that the CES-D should be considered a measure of general distress. CLINICAL UTILITY Although the CES-D was developed to measure the severity of depressive symptoms in community samples and shows internal and test-retest reliability, validity studies suggest that the measure is not specific for depression. In this way, the CES-D is similar to several other self- report depression scales used as first-stage screening devices in general community or primary care studies. Indeed, validity data obtained with the CES-D are comparable to those obtained with the BDI and the Zung SDS when they are used as first-stage screening devices. Thus, although the scale was developed to assess depression in community surveys, studies do not support its use in undiagnosed populations without a follow-up interview. REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, et al: Screening for depression in a community sample: understanding the discrepancies between depression symptom and diagnostic scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:1195–1200, 1982 Breslau N: Depressive symptoms, major depression, and generalized anxiety: a comparison of self-reports on CES-D and results from diagnostic interviews. Psychiatry Res 15:219–229, 1985 Craig TJ, Van Natta PA: Influence of demographic characteristics on two measures of depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 36:149–154, 1979 DeForge BR, Sobal J: Self-report depression scales in the elderly: the relationship between the CES-D and the Zung. Int J Psychiatry Med 18:325–328, 1988 Fechner-Bates S, Coyne JC, Schwenk TL: The relationship of self-reported distress to depressive disorders and other psychopthology. J Consult Clin Psychol 62:550–559, 1994 Gerety MB, Williams JW Jr, Mulrow CD, et al: Performance of case-finding tools for depression in the nursing home: influence of clinical and functional characteristics and selection of optimal threshold scores. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:1103–1109, 1994 Husaini BA, Neff JA, Harrington JB, et al: Depression in rural communities: validating the CES-D scale. Journal of Community Psychology 8:20–27, 1980 Myers JK, Weissman MM: Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 137:1081–1084, 1980 Naughton MJ, Wiklund I: A critical review of dimension-specific measures of healthrelated quality of life in cross-cultural research. Qual Life Res 2:397–432, 1993 Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977 Roberts RE: Reliability of the CES-D in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res 2:125– 134, 1980 Roberts RE, Vernon SW: The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 140:41–46, 1983 Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, et al: Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 106:203–214, 1977 CENTER FOR EPIDEMIOLOGIC STUDIES—DEPRESSION SCALE Circle the number of each statement which best describes how often you felt or behaved this way – DURING THE PAST WEEK. Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) Some or a little of the time (1-2 days) Occasionally or Most or all a moderate of the time amount of the (5-7 days) time (3-4 days) During the past week: 0 1 2 3 1) I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me 0 1 2 3 2) I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor 0 1 2 3 3) I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family and friends 0 1 2 3 4) I felt that I was just as good as other people 0 1 2 3 5) I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing 0 1 2 3 6) I felt depressed 0 1 2 3 7) I felt that everything I did was an effort 0 1 2 3 8) I felt hopeful about the future 0 1 2 3 9) I thought my life had been a failure 0 1 2 3 10) I felt fearful 0 1 2 3 11) My sleep was restless 0 1 2 3 12) I was happy 0 1 2 3 13) I talked less than usual 0 1 2 3 14) I felt lonely 0 1 2 3 15) People were unfriendly 0 1 2 3 16) I enjoyed life 0 1 2 3 17) I had crying spells 0 1 2 3 18) I felt sad 0 1 2 3 19) I felt that people disliked me 0 1 2 3 20) I could not get “going” 0 1 2 3