stalking - The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong

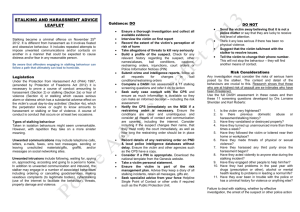

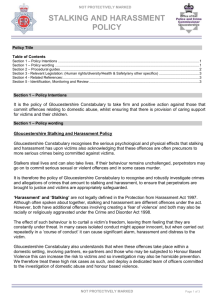

advertisement