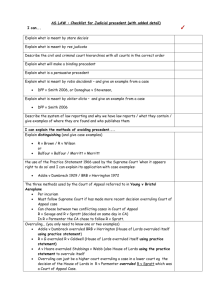

INTRODUCTION - A Level Law

advertisement

1 Task: Complete the following diagram on the Criminal Court structure. Draw the court names in the boxes and whether they are an appeal court or trial court. Draw arrows showing the routes of appeal. Magistrates Court 2 Key Terms Number Word/phrase Meaning 1 Precedent Where a judge from one of the higher courts (Court of Appeal or House of Lords) makes a legal ruling about a case then similar future cases must follow this principle, e.g. what the meaning of oppression is. 2 Original Precedent Where a case brings about a new legal decision never covered by the courts before 3 Binding Precedent Precedent on a point of law, which must now be followed by judges in a similar case. Either a senior court or sometimes one on the same level must hear the case. 4 Persuasive Precedent A precedent not binding on the court but the judge may consider it & decide that it is the correct legal principle to follow, i.e. he is persuaded. 5 Ratio Decidendi The legal reason for a decision – the part of a judges judgment that is binding on all other similar cases 6 Obiter dicta Things said by the way – the part of a judge’s judgment which is not binding on other similar cases but can be used if felt appropriate in future cases 7 Overruling A decision in the current case, which states that a legal rule in an earlier case is wrong 8 Reversing Where a higher court in the same case overturns the decision of the lower court 9 Stare Decisis Stand by the decision – Any precedent set by a higher court must not be changed 10 Distinguishing Where the material facts in the current case are different from those in a potential binding precedent a judge in any court does not need to follow the previous precedent. 3 11 Hierarchy of courts An important rule about which courts are more important in terms of making precedents. The lower courts must follow the precedents set by the higher courts, e.g. The Supreme court precedents must be followed by all courts below it. 12 Disapprove Judges may disapprove of a precedent, which they are nevertheless bound to apply, in the hope that it will be reconsidered. A superior court may also disapprove of a precedent created by a lower court without actually over ruling the precedent. 13 Per incuriam By mistake – carelessly or without taking account of a legal rule 14 Prima facie At first sight – On the face of it 4 INTRODUCTION It is said that the judges declare law the theory being that they do not make it. It is their task to state the law as they find it and apply it to the case before them. In practice however they are constantly faced with situations where what they do amounts to making new law. 1 in a million sued by M&S over registered domain names Even so, where possible they do base their decisions on previous Judge made law (known as judicial) decisions on similar facts. Note that the word used here is "similar" because it would never be the case that two factual situations were identical. What is important is that the facts that matter are the same. These are known as the material facts and where they are the same as a previous case it is in the interests of justice that like cases should be treated alike. For example, taking a hypothetical case involving a road accident, some factual differences between the present case and a previous one would be unimportant. The colour of the car or the clothes the drivers were wearing would be unlikely to matter very much. On the other hand, the speed of the cars, the condition of the road, whether or not it was dark, could well be very important facts indeed. If there are no material differences the previous decision is a precedent and if it was made in a higher court it is a binding precedent: - i.e. one, which must be followed. 5 Group exercise on judicial precedent Read the scenario and then answer the questions below In our system of judicial precedent, lower courts must follow the decision of a higher court if the material facts of a case are sufficiently similar. Consider the following two situations. Situation One On a fine sunny day a 37-year-old female motorist hurrying to a business appointment exceeded the speed limit by 10 miles per hour. This was in a busy shopping street. The motorist hit a pedestrian who had just stepped off the kerb without looking round. At the time the pedestrian was listening to a personal stereo and failed to hear the approaching car, The pedestrian sued the motorist claiming compensation for the injuries he suffered. The court held the motorist to be negligent, but found the pedestrian to be 30% to blame and reduced his compensation by that amount. Situation Two On a grey rainy day a 67-year-old male motorist hurrying to pick up a friend from the station, exceeded the speed limit by 10 miles an hour. This happened in the same shopping street, but there were only a few shoppers about. The motorist hit a 14 year old girl who had just stepped off the kerb without looking round, the girl was deaf and due to this disability had failed to hear the car approaching. If the girl sues the motorist for compensation for the injuries she has suffered, will the court use the previous case as a precedent? Are the material facts sufficiently similar? 6 This in essence is the doctrine of judicial precedent: i.e. that if a judge finds that there has been one previous decision by a higher court in a similar case he must follow it. The previous decision is the law on the matter - i.e. judge made law or case law. The principle that it must be followed is known as stare decisis - to stand by decisions. Of course, if there are material differences between two cases then the judge can distinguish the earlier decision and it doesn't have to be followed. 7 Activity: Complete the following questions after reading the diagram How Precedent Works When the judge does decide which party has won the case he makes a speech in which he reviews the case. This speech is called the judgment. The contents of this speech usually include the following: 1. The facts of the case 2. The Ratio decidendi 3. Obiter dicta 4. The decision The most important part of all this is where the judge explains the legal principle on which he has based his decision. The words in which he expresses this are called the "ratio decidendi" (the reason for deciding). All the other words in the judgment are called "obiter dicta" (things said by the way). For example, a judge saying what he would do in a hypothetical situation that is just slightly different from the actual case would be obiter. The ratio decidendi is the binding part of the judgment. Obiter dicta can be a persuasive precedent. 9 Example Consider these two cases which concern the tort of negligence: Donoghue v Stevenson (1932). Here the plaintiff suffered through finding the remnants of a decomposed snail in ginger beer, which she was drinking. She sued the manufacturer. It was held that he owed his consumers a duty to take care since he and they were "neighbours” in law. Lord Atkin said: "You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who then, in law, is my neighbour? The answer seems to be persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question." This was the original precedent and since 1932 the whole of the law of negligence has developed from it and many cases have been bound to follow it, not least the one below. Ross v Caunters (1979) A solicitor drew up a will. There was a gift in it to the wife of one of the witnesses. The Wills Act 1837 S.I5 prevented her taking it because she was his wife and such people (i.e. witnesses or their spouses) cannot be beneficiaries. Therefore it was very careless of the solicitor to let that situation arise. She sued the solicitor for negligence. It was argued that there could be no negligence because the solicitor owed the claimant no duty of care, that they were not 'neighbours’ in law. However, Sir Robert Megarry V-C said: “The solicitors owed a duty of care to the plaintiff since she was someone within their direct contemplation as a person so closely and directly affected by their acts and omissions in carrying out their client's instructions to provide her with a share of his residue that they could reasonably foresee that she would be likely to be injured by those acts or omissions.” This is a direct application of the principle established by Donoghue v Stevenson. These two cases may appear quite different. However, they are close enough for the first to be a binding authority on the second. The essence is the same even though the circumstances are radically different. 10 Note that for the proper working of the doctrine of precedent there are three essentials: A comprehensive and reliable system of law reporting, because judges cannot follow previous decisions unless they have some way of knowing about them; 1. A court hierarchy of some kind, so that judges know which decisions they must follow and which they are allowed to overrule; 2. Some way of identifying the parts of a judgment that are binding, and of separating them from any other things the judge might say. 11 Judicial Precedent Word Search Try and complete the word search. Can you guess the full case name with just one word as a clue. QYPGLWZCDAYQEFB XMREAUZIWSHPTHI CKECSPCEKECOMWE WCCSLTPMDZADGEW QPECANEEUDRPXKC JTDKXPCCAXEEETS LJEITIEDILIDYOD YDNFDYVRCTHYEBG WJTERMCPSQCUPNR VCNLAICIDUJAIIA QDLONDONBOADRTT IFCBHQZIEHNSGPI DGVVEUIDYISCIFO VAIFUIKWBTKVDVF DISTINGUISHINGE APPEAL BINDING DECIDENDI DICTA DISTINGUISHING HIERACHY JUDICIAL LONDON PERSUASIVE PRACTICE PRECEDENT RATIO 12 Re S (adult: refusal of medical treatment) FAMILY DIVISION SIR STEPHEN BROWN P 12 OCTOBER 1992 Medical treatment — Adult patient - consent to treatment — Right to refuse consent — Refusal on religious grounds - Discretion of court to authorise emergency operation — Health authority seeking authority to carry out emergency Caesarian section operation on pregnant woman - Operation in vital interests of patient and unborn child — Patient objecting objecting to operation on religious grounds – Whether court should exercise inherent jurisdiction to authorise operation. A health authority applied for a declaration to authorise the surgeons and staff of a hospital under the authority’s control to carry out an emergency Caesarean section operation upon a 30-year-old woman patient who had been admitted to hospital with ruptured membranes and in spontaneous labour with her third pregnancy and who had continued in labour since then. She was six days overdue beyond the expected date of birth and had refused, on religious grounds, to submit herself to such an operation. The surgeon in charge of the patient was emphatic in his evidence that the operation was the only means of saving the patient's life and that of her baby could not be born alive if the operation was not carried out. Held – The court would exercise its inherent jurisdiction to authorise the surgeons and staff of a hospital to carry out an emergency Caesarean section operation upon a patient contrary to her beliefs if the operation was vital to protect the life of the unborn child. Accordingly, a declaration would be granted that such an operation and any necessary consequential treatment which the hospital and its staff proposed lo perform on the patient was in the vital interests of the patient and her unborn child and could be lawfully performed despite the patient's refusal to give her consent to (the operation (see p 672 c d and g, post). Notes For consent to medical treatment, see 30 Halsbury’s Laws (4th edn reissue) para 39, and for cases on the subject, see 33 Digest (Reissue) 273, 2242-2246. Cases referred to in judgment AC, Re (1990)73 A 2d 1235, DC Ct of Apps (en bane). T (adult: refusal of medical treatment). Re [1992] 4 All ER 649, CA. Application A health authority applied for a declaration to authorise the surgeons and staff of a hospital under the health authority's control to carry out an emergency Caesarean operation on a patient, Mrs S. The facts are set out in the judgment. Huw Lloyd (instructed led by Beachcroftt Stanleys) for the health authority. James Munby QC (instructed by the Official Solicitor) as amicus curiae. SIR STEPHEN BROWN P. This is an application by a health authority for a declaration to authorise the surgeons and staff of a hospital to carry out an emergency Caesarean operation upon a patient, who I shall refer to as 'Mrs S'. 13 All England Law Reports [1992] 4 All ER Mrs S is 30 years of age. She is in labour with her third pregnancy. S was admitted to a hospital last Saturday with ruptured membranes and in spontaneous labour. She had continued in labour since. She is already six days overdue beyond the expected date of birth, which was 6 October, and she has now refused, on religious grounds, to submit herself to a Caesarean section operation. She is supported in this by her husband, They are described as 'born-again Christians' and are clearly very sincere in their beliefs. I have heard the evidence of P, a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons who is in charge of this patient at the hospital. He has given, succinctly and graphically, a description of the condition of this patient. Her situation is desperately serious, as is also the situation of the as yet unborn child. The child is in what is described as a position of 'transverse lie', with her elbow projecting through the cervix and the head being on the right side. There is the gravest risk of a rupture of the uterus if the section is not carried out and the natural labour process is permitted to continue. The evidence of P is that we are concerned with 'minutes rather than hours' and that it is a 'life and death' situation. He has done his best, as have other surgeons and doctors at the hospital, to persuade the mother that the only means of saving her life, and also to emphasise the life of her unborn child, is to carry out a Caesarean section operation. P is emphatic. lie says it is absolutely the case that the baby cannot be born alive if a Caesarean operation is not carried out. He has described the medical condition. I am not going to go into it in detail because of the pressure of time. I have been assisted by Mr Munby QC appearing for the Official Solicitor as amicus curiae. The Official Solicitor answered the call of the court within minutes and, although this application only came to the notice of the court officials at 1.30pm, it has come on for hearing just before 2 o'clock and now at 2.30 pm I propose to make the declaration which is sought. I do so in the knowledge that the fundamental question appears to have been left open by LORD Donaldson MR in Re T (adult: refusal of medical treatment) [1992] 4 All ER 649, heard earlier this year in the Court of Appeal, and in the knowledge that there is no English authority which is directly in point. There is, however, some American authority which suggests that if this case were being heard in the American courts the answer would be likely to be in favour of granting a declaration in these circumstances: see Re A C (1990) 573 A 2d 1235 at, 1210, 1246-1248, 1252. I do not propose to say more at this stage, except that I wholly accept the evidence as to the desperate nature of this situation, and that I grant a declaration as sought: Declaration that a Caesarean section and any necessary consequential treatment which the hospital and its staff proposed to perform on the patient was in the vital interests of the patient and her unborn child and could be lawfully performed despite the patient's refusal to give her consent. No order as to costs. Bebe Chua Barrister. 14 How precedent works – the key rules Judicial precedent is the process whereby judges follow previously decided cases where the facts or point of law are sufficiently similar. The Key features of the rules on precedent are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The The The The The The The The hierarchy of courts need for original precedent importance of stare decisis importance of binding precedent need for accurate law reports importance of ratio decidendi – reason for the decision importance of obiter dicta – other things said by the way importance of persuasive precedent The hierarchy of court The courts have a strict order in terms of precedents which they must follow (binding precedent). This is based on the fact that the higher the court the more expertise and experience the judges have. Also the higher the Appeal court the more judges are required to consider the case. Appeal courts are also normally dealing with many more unique issues on points of law than those in lower courts so again have more expertise. Task: Using the table below complete the exercise on the hierarchy of courts on page 7. 15 Court European Court of Justice How precedent operates Under s3(1) of the European Communities Act 1972, decisions of the ECJ are binding, in matters of EU law, on all English courts. It is not bound by its own previous decisions. The court does not bind any English Criminal courts, it is Civil courts only starting with the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court The Supreme Court is bound by the European Court of Justice on Civil matters and EU law. The supreme court binds itself (but see below) and all courts below it on Civil law. For Criminal Law the Supreme Court binds itself (but see below) and all courts below it. The House of Lords was not bound by its own previous decisions until the case of London Street Tramways v London County Council (1898) when it bound itself in the interests of certainty. The Court of Appeal Then the Practice Statement (1966), issued by the Lord Chancellor, stated that although the House of Lords would treat its decisions as normally binding it would depart from these when it appeared right to do so Is split into the Criminal and Civil division. The Court of Appeal is bound by decisions of the Supreme Court even if it considers them to be wrong. The Court of Appeal binds itself and all the courts below it. But the Civil and Criminal division do not bind each other as they are different types of law. Divisional Court of the High Court The High court Crown, County & Magistrates Court A Divisional Court is bound by the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal and normally follows a previous decision of another Divisional Court if the law is of a similar type. The High Court is bound by the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court but is not bound by other High Court decisions. However, they are of strong persuasive authority in the High Court and are usually followed. The decisions of these courts are not binding but can be persuasive. 16 Original precedent Clearly there has to be a case that is regarded as the first of its kind to develop a new legal rule. This is called an original precedent. All courts can make an original precedent but only some courts can make this binding for future courts to follow. An example of an original precedent is Donoghue v Stevenson, as shown in detail previously. Task: Re S is another example of an Original precedent. Make a case note that you could you use to answer and exam question on Original precedent. Stare Decisis Stare decisis, which mean to stand by the decided, whereby lower courts are bound to apply the legal principles set down by superior courts in earlier cases. For example, the High Court must follow decisions of the Court of Appeal, which must follow decisions of the House of Lords/Supreme court. This is an important principle as it recognises a fair and democratic society needs laws that alter rarely over time. Society can then be sure what they can and can’t do in their daily lives and the consequences of breaking the law. The principle links closely to that of binding precedent. Donoghue v Stevenson (1932): The decomposing snail in the bottle of ginger beer case (see above). The HoL held that a manufacturer owed a duty of care to the consumer that products are safe. “Products” have since been held by later courts to include not only food and drink but also, underpants, motor cars, hair dye, lifts and chemicals. This case had to be followed due to Stare decisis by the later case of: Grant v Australian Knitting Mills (1936): The claimant bought some underwear but the material contained a chemical which caused dermatitis. Compensation was awarded based on the precedent set by Donoghue v Stevenson. This was because the HoL was a higher court than the Court of Appeal and was a binding precedent, one which lower courts have to follow where the material facts are similar. 17 Binding precedent Is closely linked to stare decisis and is the part of the judgment that must be followed by future judges, where the material facts (most important facts for the legal rule) are similar. Binding precedent can only be found in the ratio decidendi of the judgment, i.e. the reasons the judge came to a specific decision in the current case. Binding precedent can only be created by: 1. 2. 3. 4. The Supreme Court The Court of Appeal, Civil and Criminal Division Divisional Court of the High court The High Court as an appeal court for Civil or Criminal cases. The Crown, County and Magistrates court cannot make binding precedent. However, they must follow binding precedents of courts higher up in the hierarchy. The rules about binding precedent are: 1. Any court who has made a binding precedent must follow this themselves in future similar cases – stare decisis 2. Any court below the one making the binding precedent must follow it in future similar cases 3. Any court above the one who made it in the hierarchy does not have follow the precedent as it is not regarded as binding on this court. However, Stare decisis and the need for a consistent approach to the predictability of law means that case will be a strong persuasive precedent for these courts. In otherwords, there must be a very good reason to decide a different approach. Case examples are as per Stare Decisis. 18 19 Law Reporting If the court is to follow an earlier decision, then the report of that earlier case must be authoritative. This was finally achieved in 1865 when the General Council of Law Reporting was established. It was incorporated in 1870. The Law Reports and Weekly Law Reports are published under the auspices of this Incorporated Council. They are of great authority and are checked by the judges and barristers before publication. As well as these there are still private reports published, as there have been over the centuries. Probably the most famous are the All England Law Reports. Yet another example is The Times Law Reports. A lot of law reports can now be accessed on line via Lexis or Bailii, but cost a lot of money. Reports follow a common format and are normally split into Name of the case and the court where it takes place, the date of the judgment, the name of the judge and barristers, a summary of the facts of the case, the judgment of the judge and a short summary of which area(s) of the law the case affects. An example of a private law report is Re S, which was reported in the All England Law reports and is a very important original precedent on the issue of consent to medical treatment where the patient has refused to have a lifesaving operation both herself and her unborn baby. An example of using an electronic law report is Bailii’s report on the case of Donoghue v Stevenson, which is a fundamental case establishing a general duty of care between manufacturers’ of goods and those that consume them. Ratio Decidendi Literally means the reason for the decision as it is the most important part of any written judgment. It is the legal rules that have been applied to the case leading to the final decision, guilty or not guilty in a criminal case or liable or not liable in a civil case. The ratio decidendi will form the binding precedent for any future similar cases particularly the higher up the hierarchy the judgment is made. It will also form the original precedent if this is the first case of its kind. 20 R v Dudley & Stevens (1884): The two shipwrecked defendants killed and ate the cabin boy. They were convicted of murder. The D’s argued that it was the lesser of two evils to kill one person compared to 3 people dying, they did it through a necessity to live. The court gave three reasons, the ratio decidendi, for refusing a defence of necessity: 1. If necessity is not available on a charge of theft of food because of starvation, it cannot be available to a charge of murder 2. The Christian aspect of giving up one’s own life to save another’s rather than taking another’s life to save one’s own 3. Impossibility of choosing between the value of one person's life and another's. R v Howe (1987) The two defendants helped torture a man who was then killed by other men and, on a later occasion, killed another man. They were both threatened with death unless they took part. The HoL refused a defence of duress to charges involving murder because (the ratio decidendi) of the need to protect innocent lives and to set a standard of conduct which all people are expected to observe in order to avoid criminal liability. The HoL made it clear that no one’s life was worth more than another Task: Now apply Dudley & Stevens to the case of R v Quayle & others 2005: Five appeals were jointly heard with one Attorney General Reference. Each case was concerned with the applicability of the defence of necessity in relation to offences involving, possession, cultivation, production and importation of cannabis. In all the appeals the appellants argued that the cannabis was for medical purposes for the relief of pain for various medical ailments including HIV, Multiple sclerosis and severe back pain. 21 Obita Dicta Is also part of a judge’s judgment and literally means other things said by the way. Obita dicta cannot be binding precedent but can persuade other courts to adopt the legal rules in future cases, it is persuasive precedent. Obita dicta can be helpful to future judges as it may give ideas on how to approach cases that are slightly different from the current one. The higher the court is in the hierarchy making the obita dicta the more important it will be in future cases. R v Howe 1987 See notes before for the facts of the case. In obita dicta the HoL also gave their opinion on whether the defence of duress would be available to a D who had attempted to kill a V, due to being threatened with death or serious injury. They believed that in such a situation the D should also be denied the defence for the same reason as it is not allowed for someone who actually commits murder. R v Gotts 1992 The appellant, a 16 year old boy, was ordered by his father to kill his mother otherwise the father would shoot him. He stabbed his mother causing serious injuries but she survived. He was charged with attempted murder and the trial judge ruled that the defence of duress was not available to him. He pleaded guilty and then appealed the judge’s ruling to the Court of Appeal. The appeal was dismissed and his conviction upheld. The House of Lords followed the obiter dicta statement from R v Howe and held that the defence of duress was not available for attempted murder. The decision was based on the fact that it would be anomalous to allow the defence to attempted murder, which can only be established where the defendant has an intention to kill, whereas murder can be established with a lower level of mens rea since it can be committed by one who intends to cause serious injury. Hill v Baxter The defendant driver fell asleep and drove into some people. His conviction for driving offences was upheld as he was at fault for not stopping when he felt drowsy. The judge went on to give the fictional example of someone being stung by a swarm of bees while driving, and losing control of the car as an example of a driver not being at fault. 22 Persuasive precedent A persuasive precedent is one which is not absolutely binding on a court but which may be applied. All courts can make persuasive precedents. Criminal courts cannot make binding precedent for Civil courts and vice versa. However, Civil precedent can be persuasive precedent for criminal courts and vice versa. The following are some types of persuasive precedent: 1. 2. 3. 4. Decisions of English courts lower in the hierarchy Decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Obita Dicta Dissenting judgments Decisions of English courts lower in the hierarchy For example, the House of Lords may follow a Court of Appeal decision, and the Court of Appeal may follow a High Court decision, although not strictly bound to do so. R v R (1991) the marital rape case where the HL followed the decision of the CA and held the husband to be liable for the rape of his wife Decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. This is the Same Supreme Court judges who meet as a court for another legal system. A lot of colonies and ex colonial countries still use our legal system as the final appeal court for their country. As another countries legal system is different to our legal system the courts decisions are normally only persuasive precedent. However, in the case below this rule was modified so that when there are a large number of Supreme Court judges sitting as the Privy Council and precedent being set is exactly the same as the law in England then effectively it becomes a binding precedent. AG Ref Jersey v Holley 2005 A landmark case where the Privy Council declared that they were announcing the law applicable not only to Jersey but also to England and Wales. (Privy Council decisions are not generally considered binding in English law but of mere persuasive authority). The Judicial Committee consisted of nine members of the House of Lords. The defendant had a stormy relationship with the deceased. They were both alcoholics and he had a history of violence towards her for which he had spent time in prison. On his release from prison she indicated that she did not want to continue the relationship. However, they continued to live together having constant rows. On the day 23 in question they had both been to the pub in the afternoon. He returned early because of an argument. She returned in the evening and announced that she had had sex with another man. He hacked her to death with an axe. At his trial he raised the defence of provocation. He wished to rely on his alcoholism, depression and other personality traits. The jury convicted him of murder. The defendant appealed to the Court of Appeal who quashed the conviction and ordered a retrial. He was again convicted at the retrial and again appealed. His conviction was again quashed and a manslaughter conviction was substituted. The Attorney General sought leave to appeal arguing the decision in Smith (Morgan) was wrong and should not apply in Jersey. Held: 6:3 Decision (Lords Carswell, Bingham and Hoffman dissenting) The appeal was allowed. The law in Jersey and England & Wales is the same on this issue. The decision in Smith (Morgan) allowing mental characteristics to be attributed to the reasonable man in assessing the standard of self-control expected of the defendant is no longer good law. Decisions of the courts in Scotland, Ireland, the Commonwealth (especially Australia, Canada and New Zealand), and the USA. As all these countries have legal systems based on the English common law legal system judgments can be relevant to helping judges with new or unusual cases. These are usually cited where there is a shortage or total lack of English authority on a point. For example, Re S (adult: refusal of medical treatment) (1992). See previously for facts. Here the High court and later the HoL relied on a US persuasive precedent from an earlier case which stated that where the mother was refusing a caesarean and the life of the mother and child were at risk the court could authorise the lifesaving treatment against the mothers will as it was in the best interests of the unborn child. Obita dicta – Is a persuasive precedent. See previous for details. Dissenting judgments All appeals in the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court are decided by majority decision. Anyone in the minority are called dissenting judges and give a dissenting judgment. These can be used by courts in future cases to act as a persuasive precedent as the dissenting judge may have actually been correct afterall or the suggestion as to how the law should develop is now relevant. See attached article for detailed review of the value of dissenting judgments. 24 Candler v Crane Christmas & Co 1951: Donald Ogilvie was the director of a company called Trevaunance Hydraulic Tin Mines Ltd, which mined tin in Cornwall. He needed more capital, so he put an advertisement in The Times on July 8, 1946, which said “Established Tin Mine (low capitalization) in Cornwall seeks further capital. Install additional milling plant. Directorship and active participation open to suitable applicant – Apply” Mr Candler responded, saying he was interested in investing £2000, if he could see the company's accounts. Mr Ogilvie instructed Crane, Christmas & Co, a firm of auditors, to prepare the company’s accounts and balance sheet. The draft accounts were shown to Mr Candler in the presence of Crane, Christmas & Co’s clerk. Mr Candler relied on their accuracy and subscribed for £2,000 worth of shares in the company. But the company was actually in a very bad state. Ogilvie used the investment on himself and then went bankrupt. Mr Candler lost all the money he invested. He brought an action against the accountants, Crane, Christmas & Co. for negligently misrepresenting the state of the company. As there was no contractual relationship between the parties, the action was brought in tort law for pure economic loss. The majority of the HoL stated that the accountants could not be sued by Mr Crane relying on their poor investment advice. However Lord Denning, the only dissenting judge, stated “In my opinion accountants owe a duty of care not only to their own clients, but also to all those whom they know will rely on their accounts in the transactions for which those accounts are prepared. I would therefore be in favour of allowing the appeal and entering judgment for the plaintiff for damages in the sum of £2,000.” In the later case of Hedley Bryne v Heller 1963, as similar facts case, the HoL decided to change the law and follow Lord Denning’s dissenting judgment in Candler. Therefore accountants can be sued for damages by investors that rely on their poor advice under certain conditions. 25 Methods of avoiding precedent The problem with the system of precedent is that though it works well for the majority of cases but for a small number of cases the precedent the judge has to follow may be an unfair approach to a unique situation. Another problem is that as society changes economically, technologically or socially the past precedents no longer are relevant to today’s society. So there are a range of methods available in precedent to allow for exceptions or all out change. The higher the court is in the hierarchy the more powers the court has to alter previous precedents: Distinguishing Any court can avoid a binding precedent where the material facts in the case are different from those in the binding precedent, in otherwords it is effectively a new precedent. Distinguishing a case on its facts, or on the point of law involved, is a device used by judges to usually in order to avoid the consequences of an earlier inconvenient decision which is, in strict practice, binding on them. Any judge can distinguish a precedent on minute details and the differences can sometimes seem illogical. Distinguishing does allow judges to develop the law and create exceptions to a general rule established in a previous case. Balfour v Balfour 1919: The D and V were married when the D went off to Ceylon and told his wife he would support her by giving her an allowance. Sometime later they fell out and the husband stopped paying the allowance. The court decided that as there was no written agreement and they were not legally separated at the time the agreement was made there was no intentions to create legally binding contract to pay the money. The husband therefore did not need to pay any further allowance. Merritt v Merritt 1971: A husband legally separated from his wife and went to live with another woman. There was £180 left owing on the house which was jointly owned by the couple. The husband signed an agreement whereby he would pay the wife £40 per month to enable her to meet the mortgage payments and if she paid all the charges in connection with the mortgage until it was paid off he would transfer his share of the house to her. When the mortgage was fully paid she brought an action for a declaration that the house belonged to her. 26 Task: Compare the material facts (the most important facts) for deciding the case in Balfour with the material facts in Merritt. The two most important facts to deciding that there was no intention to create a legal relationship in Balfour are: 1. Not legally separated at the time of the agreement 2. No written agreement between the couple The two most important facts in deciding whether or not the judge must follow the precedent of Balfour in Merritt are: 1. The couple were legally separated at the time of the agreement 2. The agreement was in writing The judge can use distinguishing in the case of Merritt because.. There are two material facts in the case that make it different from Balfour, they distinguish the precedent of Balfour from that of Merritt. In the case of R v Jordan 1956 the D had stabbed the V but the wounds had almost healed. However not only did the first doctor give V a large dose of antibiotics to which he had an allergic reaction, but a second doctor then did not read the notes stating this and administered a fatal second dose of antibiotics. The case of R v Smith 1959 the D was similar in that there was a stabbing but only one doctor missed the fatal stab wound which was still bleeding at the time of V’s death. So as the material facts were different Smith did not have to be bound by the precedent of Jordan. Reversing Reversing is the overturning on appeal by a higher court, of the decision of the court below that hearing the appeal. The appeal court will then substitute its own decision. This can only be carried out by a court with enough authority, such as a Divisional Court, the CA or HoL. R v Kingston (1994) K was invited back to his business partner’s flat where he consumed a drink that had been spied with alcohol. K was then shown to a bedroom where a young boy had been sedated and K performed sexual acts on him. K argued that as his drink had been spiked he was not responsible for his actions and therefore not guilty of the sexual assault. On appeal to the CA they agreed with K and said that involuntary intoxication would mean K lacked the awareness of committing the crime. On further 27 appeal to the HoL by the _____________ the court reversed the decision of the CA and held that involuntary intoxication will not be a defence unless it prevents the defendant forming mens rea for the crime charged even though the defendant was not at fault for becoming intoxicated. A drunken intent to perform sexual acts still was an awareness of committing the crime. The power to disapprove Judges may disapprove of a precedent, which they are nevertheless bound to apply, in the hope that it will be reconsidered. A superior court may also disapprove of a precedent created by a lower court without actually overruling it. Elliott v C: The defendant was a 14-year old girl of low intelligence who had started a fire in a shed. She had poured white spirit on the floor and set it alight. She was found guilty of criminal damage as she had taken an unjustified risk a reasonable man would not have taken, i.e. set fire to a wooden shed to keep warm knowing this stood a high chance of burning down the shed. It was held that the trial court should have applied the test for recklessness in the case of MPC v Caldwell, which was one where the age and medical condition of the girl could not have been taken into account when looking at whether the D had taken an unjustified risk in setting fire to the shed. The Appeal court disapproved of the case of Caldwell as it meant the jury/Magistrates could only consider whether or not they could foresee the unjustified risk of starting a fire in someone else’s shed and not what the D actually foresaw as an unjustified risk. The HoL later changed the law by overruling MPC v Caldwell in the case of R v G & R so that to be guilty of criminal damage the jury/magistrates should look at what D foresaw as an unjustified risk. The power to overrule A higher court can overrule a decision made in an earlier case by a lower court e.g., the Court of Appeal can overrule an earlier High Court decision. The ECJ and House of Lords can also overrule their own previous decisions. 28 In the case of Hedley Bryne v Heller 1963 the HoL overruled the Court of Appeal’s previous decision in Candler v Crane 1951 stating that an accountant did not have to pay compensation for negligent advice given to a 3rd party investor, stating incorrectly that investment in a company was a good bet. 29 The House of Lords Practice statement in 1966 The Practice Statement said the HoL would overrule their own previous decisions when the court believed it was “right to do so”. See the copy of the Practice statement below. It is NOT a case, simply a statement of intent by the HoL. 30 The practice statement was accompanied by a press release, which emphasised the importance of and the reasons for the change in practice: 1. It would enable the House of Lords to adapt English law to meet changing social, economic and technological conditions. 2. It would enable the House to pay more attention to decisions of superior courts in the Commonwealth, e.g. Jamaica, The Bahamas 3. The change would bring the House into line with the practice of superior courts in many other countries. In the USA, for example, the US Supreme Court and state supreme courts are not bound by their own previous decisions. 4. However, the practice statement has been rarely used by the HoL The first real use of the Practice Statement was in 1972 for Civil law. This recognised social changes in society for increasing obligations owed to young children who trespassed on their land. BRB v Herrington 1972: A six year old boy was electrocuted and suffered severe burns when he wandered from a play park onto a live railway line. The railway line was surrounded by a fence. However, part of the fence had been pushed down and the gap created had been used frequently as a short cut to the park. The defendant was aware of the gap in the fence which had been present for several months, but had failed to do anything about it. Under previous precedent of the HoL of Addie v Dumbreck 1929 no duty of care was owed to trespassers, including children. However, the House of Lords departed from their previous decision using the 1966 Practice Statement and held that the defendant railway company did owe a duty of common humanity to child trespassers. This overruled their previous precedent. The first case of Criminal law that used the Practice Statement was not until 20 years after the Practice Statement. If you look at the Practice Statement above you will see why, can you work it out? The Practice Statement was used to correct an error made in the application of an Act of parliament, the Criminal Attempts Act 1981. Anderton v Ryan 1985: The D bought a stolen video recorder in a pub and was later charged with theft and handling stolen goods. Later the charge of theft had to be dropped as there was insufficient evidence to prove this offence. The D was now charged with attempting to handle stolen goods. Attempted crimes are as serious as if the D had managed to commit the full offence and are charged under the Criminal 31 Attempts Act 1981. However, the crime was effectively made impossible as the P could not prove the goods were stolen so how could the D attempt to “steal” goods that aren’t legally stolen. The HoL decided that D was charged with an impossible crime and therefore could not be found guilty of attempting it. However the HoL made an error in law by not considering S 1(2) of the Criminal Attempts Act: (2)A person may be guilty of attempting to commit an offence to which this section applies even though the facts are such that the commission of the offence is impossible. R v Shivpuri: The defendant was paid to act as a drugs courier. He was required to collect a package containing drugs and to contribute its contents according to instructions which would be given to him. When the defendant collected the package the defendant was arrested by police officers he confessed to them that he believed its contents to be either heroin or cannabis. An analysis revealed the contents of the package not to be drugs, but a harmless vegetable substance. The defendant was convicted for attempting to be knowingly concerned in dealing and harbouring a controlled drug, namely heroin. The House of Lords took the opportunity of making it clear that, even though Anderton v Ryan had only been decided by them a short time before, they now felt that their earlier decision was wrong and that they were overruling that decision and declaring the law to be as they found it to be in Shivpuri, attempting an impossible was an offence under S1(2) of the Criminal Attempts Act. Court of Appeal (CA) powers The CA have powers such as having the power to overrule, distinguish or disapprove any precedent from a lower court (not the Supreme Court). The CA cannot overrule its own precedents eventhough the court is effectively the final appeal court for the vast majority of Civil and Criminal cases. Few cases are either important enough to go to The Supreme Court or can afford to pay for an appeal to the Supreme Court. The Criminal division of the CA does not bind the Criminal Division in terms of precedent as they are different types of law, though they can be persuasive precedent. As the CA is final appeal court for most cases they do have special powers. In civil cases the powers are contained in the case of Young v Bristol Aeroplane. 32 The special rules to vary a precedent in the Civil Division of the CA are: (1) The court is entitled and bound to decide which of two conflicting decisions of its own it will follow. As Appeals sometimes come before the CA in quick succession it may mean that a first precedent created conflicts with the second case, which has raised new issues. If this is the case the court and chose which if the two cases it wishes to make a precedent. (2) The court is bound to refuse to follow a decision on its own which, though not expressly overruled, cannot, in its opinion, stand with a decision of the Supreme Court (3) The court is not bound to follow a decision of its own if it is satisfied that the decision was given per incuriam, meaning the CA has mistakenly missed a previous precedent or Act of parliament that should have been taken into account. For Criminal cases the CA can use the Young exceptions and because the D may end up in prison can ignore a precedent if this will result in the D being unjustly imprisoned. R v Gould 1968: D remarried in the honest, but mistaken belief that his first marriage had been dissolved. He was charged with Bigamy and appealed on the grounds that a conviction would be unfair and also mean he would be unjustly imprisoned for an honest mistake made about his first marriage. The Court held that the CA criminal division did not have to follow previous binding precedent as the D would be unfairly imprisoned. Conflicting decisions example Parmenter v R 1991: D injured his child by roughly handling him and breaking the bones in his arms and legs. There was no proof that D had foreseen the risk of injury, but then had to decide whether a conviction for assault causing actual bodily harm could be substituted even though there was no evidence D foresaw risk of harm . The CA had decided in Spratt [1991] that foresight was essential to a conviction; on the same day, another part of the CA had decided in Savage [1991] that D need not himself have foreseen any risk of harm. Faced with two conflicting cases, the CA had to choose between them, and chose to follow Spratt. Note: The HoL later reversed this decision in favour of following Savage, the current law. This is an important case for the mens rea of the offence S47 ABH you will study. 33 Advantages and Disadvantages of Precedent Advantages Flexibility Judges in Appeal courts can reverse decision that are decided incorrectly in lower courts. So in the case of R v Kingston the HoL reversed the decision of the CA as to whether a D could argue a lack of awareness for the sexual abuse of a minor simply because his drinking of alcohol was involuntary, the drink was spiked. The HoL stated that simply the alcohol loosening the D’s inhibitions was not enough to stop him having an awareness of committing the sexual offence, the alcohol must cause the D to be unable to having any awareness of the crime before being able to have a defence. Precedent is a much more flexible approach using reversing as it allows more experienced judges to strike a more just application of the law on intoxication as a defence than achieved by less experience judges lower in the hierarchy. Dealing with real cases Unlike Parliament and Acts precedents are based on cases and people whose lives will be affected immediately by the decisions made particularly by Appeal courts. Original precedents are made only when there is a need for a development in the Law. So in Donoghue v Stevenson Lord Atkins recognised there was a need to have a general duty of care in society when those that manufactured ginger beer and other products were becoming much further away from where consumption was taking place. Not only did Donoghue receive compensation, as the manufacturer had failed to take proper care in creating the ginger beer, but this also set a binding precedent for all manufacturers to take reasonable care in producing consumer goods, dealing with the current and future cases on this issue. Providing detailed rules for later cases Unlike Acts of parliament precedents deal create very detailed rules on matters before them which are applied consistently to later cases. With binding precedent and stare decisis higher court precedents must be followed by lower courts in cases with similar facts. So Grant v Australian knitting Mills had to follow the detailed rules set out on the duty of care held by the manufacturer of undergarments to the wearer of it as they had failed to take reasonable steps to ensure their goods were fit for consumption, following through binding precedent the earlier higher court case of Donoghue. These rules have been further developed and improved to form the law of negligence covering a wider range of issues brought up in later cases such as those of car accidents. 34 Fair/just decisions Precedent can adopt to social, economic and technological change to ensure the law is fair for society’s changing needs. The HoL recognised this in the Practice Statement when they decided it was fairer to make landowners have responsibility for child trespassers who were injured on their land, in the case of BRB v Herrington. This was a fairer precedent for today’s society’s more sympathetic view of children even when trespassing compared to the HoL decision in 1929 or Addie v Dumbreck which placed blame for injuries on the child trespasser. Overrulung the HOL’s own previous precedent ensured the law reflects today fairer approach to child trespassers who are injured. Certainty The hierarchy of courts underpinned by the principle of Stare Decisis means that the vast majority of cases dealt with by trial courts such as the Magistrates and Crown Court have to follow the binding precedents of higher courts, particularly The Supreme Court. So with criminal law in particular the HoL under the Practice Statement has stated that there should only be changes to the law in exceptional circumstances to provide certainty when considering crimes that are punished harshly such as murder. The definition of murder was created in a case by Lord Coke more than 300 years ago and precedent has altered this only slightly so that defendants and their advisors can predict the results of a case with great consistency, resulting more certain outcomes in court. Disadvantages Undemocratic As judges are unelected the risk contravening the separation of powers so that instead of just applying the law the actually play too large a role in creating it. In the case of Gillick v Norfolk Health Authority Mrs Gillick was a mother with five daughters under the age of 16. She sought a declaration that it would be unlawful for a doctor to prescribe contraceptives to girls under 16 without the knowledge or consent of the parent. The court held that provided the patient, whether a boy or a girl, is capable of understanding what is proposed, and of expressing his or her own wishes, then contraception advice and issue can be undertaken without parental consent or knowledge. However, it can be argued that as the HoL are unelected judges this emotive issue should have been left for debate by parliament as they are more likely to be able to gauge public opinion on the issue before making any law. 35 Cases have to come to court & cases having to reach higher courts Unlike parliament judges must wait for an appropriate case to come to court before they can make even the most important changes to the law. So even though the HoL made a serious error in case of Anderton v Ryan, forgetting parliament had made it an offence to even attempt a crime that was impossible, they court had wait for another case to come to the HoL, R v Shivpuri, to rectify their error using overruling. As it was the HoL that made the erroneous binding precedent no other court could correct the mistake meaning trail courts such as the Crown Court would allow Ds to walk free from court in direct contravention of the law laid down by Parliament in the Criminal Attempts Act. Multiple reasons for decision Unlike an Act of parliament, where debating and voting ultimately creates just one law, in appeal courts upto 9 judges in The Supreme Court can give totally different legal reasons as to why they may or may not allow the appeal. So in Candler Crane v Christmas the majority of the judges believed there was no duty of care between the accountant for the company and the third party investor. However, in Lord Denning’s judgment he believed there should a duty of care causing potential confusion as to what the law actually was saying should happen due to multiple decisions. Difficulty in identifying ratio Judges do not make it clear which part of their judgment is the legally binding part so different lower court judges may interpret different elements of the judgment in different ways, leading to potential inconsistencies in the application of the law across similar cases. So with distinguishing the judge may identify the current case as being materially different from the binding precedent simply because it is a matter of interpretation as to what the ratio was. It could be that Merritt should have actually followed the precedent of Balfour as the judge may have incorrectly identified the ratio as being irrelevant in Balfour, leading to confusion in the law of financial agreements between separated couples. Number of precedents/diversity of law reporting As judges are always creating precedent in appeal courts based the smallest of issues in cases trying to establish what the law actually is extremely difficult, time consuming and complicated. For example, there have been many cases trying to establish what recklessness should mean when trying to prove whether or not a D was liable for a criminal offence. In some cases, like Elliot v C, judges do not overrule but simply disprove of a binding precedent, in the case Caldwell. In other cases the Appeal courts decide the law was incorrectly stated and change it. R v G& R overruled Caldwell. All these cases are reported in both the press, private law reports and by t Council of law 36 reporting leading to a very complex set of precedents that risks being misinterpreted and applied. 37 Task A Read the following passage and then answer the questions McLoughlin v O'Brien and others (1982) Ms McLoughlin was at home when a witness to a serious road accident two miles away came to tell her what had happened. The accident involved her husband and three children.When she arrived at the hospital she found her family in severe pain and covered in blood, oil and mud. She was told that her daughter had died. Ms McLoughlin suffered severe and long-term psychiatric illness as a result of this experience. She claimed against the defendants whose negligence had caused the road accident. The case was appealed to the House of Lords. Several Law Lords gave judgement in the case. Sometimes, when judges and academics look back at past cases, they decide that the judgement made by a Law Lord is the 'leading judgement' - the judgement which makes the case an authority. In this case Lord Wilberforce gave the leading judgement. Lord Wilberforce reviewed existing nervous shock cases to see where the law currently stood and what precedents must be followed: 1.Bourhill v Young (1943) recognised the possibility of claiming for nervous shock in principle. 2. Dulieu v White and Sons (1901), together with Hambrook v Stokes Bros (1925), were at one time thought to limit a claim for damages to situations where the plaintiff was afraid of immediate personal injury. Wilberforce said that these cases had 'not gained acceptance'. 3. In Hambrook v Stokes Bros (1925) it was determined that a plaintiff may only recover (i.e. receive damages) for nervous shock brought on by injury to a near relative (husband and wife or parent and child). Moreover, there was no liability where the injuries were learnt of through communication with others, rather than actually witnessing something. 4. Where the plaintiff arrives at the scene immediately after the incident, however, as was the case in Boardman v Sanderson (1964) and Benson v Lee (1972), they may be able to recover for nervous shock (so the rule in Hambrook v Stokes Bros (1925) was modified). 38 5. In Chadwick v British Railways (1967) a man who arrived in the immediate aftermath of a serious accident was allowed to recover for nervous shock even though those injured were not related to him, on the basis that he acted as a rescuer. Having set out what he took to be the current position on the law relating to nervous shock cases, Lord Wilberforce then considered the effect of these precedents on Ms McLoughlin's position. He pointed out that the facts of Benson v Lee (1972) also involved a mother who was told of her family's injuries by a bystander. In that case, the mother was 100 yards away from the scene of the accident and went straight there. Wilberforce could find no reason why this case should be decided any differently: 'Can it make any difference that she comes on them in an ambulance or, as here, in a nearby hospital, when as the evidence shows, they were in the same condition, covered with oil and mud, and distraught with pain?' What makes the judgement in McLoughlin v O'Brien and others (1982) typical of the way that the common law operates is the process of logical sifting through earlier precedents. The Law Lords who decided to grant Ms McLoughlin's appeal will have spent considerable time in a library, reading and re-reading the written judgements of other judges in earlier cases. They did not simply judge the case in isolation. Questions (a) What is a leading judgement? (2) (b) McLoughlin v O'Brien and others (1982) was heard by the Lords in 1982. In what year was nervous shock first recognised as a reason for damages? (1) 39 (c) Which precedent does Wilberforce appear to follow here? Does he regard the precedent as fundamentally different from the facts of Ms McLoughlin's case? (6) (d) Using the precedents on nervous shock, explain how as a Law Lord you would decide the two cases below. State what your decision would be and whether you would be following, distinguishing, or overruling relevant authorities: A. Ms Jones was in her home in Devon when a policeman came to tell her that her son had been severely injured in a rail crash in Glasgow a week before. She travelled to Scotland to see him in hospital. She then claimed for nervous shock against the negligent railway company. 40 B. Mr Smith was travelling home after spending Christmas with his parents. Half way home, he came upon the immediate aftermath of a very serious accident. One of the two vehicles involved was a small car which had crumpled up, trapping the driver, who was not at fault. Mr Smith gave basic first aid to the driver, who lost a great deal of blood and slipped fast into unconsciousness. When he arrived home Mr Smith, a very sensitive person, suffered from depression and nightmares for some months. He claimed, against the other driver, who was at fault. (10) 41 Task B Matching exercise Draw a line from each key word or phrase to the correct meaning. Ratio Decidendi Higher court in the same case overturns the decision Persuasive Precedent Everything else said that isn't directly relevant to the case Per incuriam Stand by what has been decided Overruling A previous decision which must be followed Original Precedent Avoiding the past case because the facts are different Obiter Dicta Reason for deciding Binding Precedent Statement that a legal ruling in a past' case is wrong Privy Council Allows the House of Lords to go against its past decisions Reversing A decision where there is no previous law to follow Practice Statement A previous decision which may be followed Stare Decisis The final appeal court for some Commonwealth countries Distinguishing Ignoring a statute or House of Lords judgment 42 Summary of Advantages and Disadvantages of Precedent 43 Precedent Past paper questions 1. With reference to the doctrine of judicial precedent, explain what is meant by the terms ratio decidendi and obiter dicta. 2. Outline the key features of the doctrine of judicial precedent 3. Outline the process of overruling and briefly explain how judges in the Supreme Court can avoid following a binding precedent. 4. Describe any two ways in which judges can avoid following an earlier precedent. 5. Using cases and/or examples, explain how the House of Lords and the Court of Appeal can avoid following a precedent. 6. Outline what is meant by the terms hierarchy of the courts and obiter dicta 7. Outline two ways by which judges can avoid following a binding precedent. 8. Explain how judges either in the Supreme Court or in the Court of Appeal can avoid following precedent. 9. With reference to judicial precedent, outline what is meant by the following terms: hierarchy of the courts ratio decidendi law reporting 10. Outline how judges can avoid following precedent by: distinguishing a previous precedent overruling a previous precedent 11. Discuss either the advantages or the disadvantages of the doctrine of judicial precedent. 12. Discuss the advantages of judicial precedent 13. Discuss the disadvantages of the doctrine of judicial precedent 44 Task C In the case of R v Shivpuri (1986) the House of Lords overruled a decision that they had made less than one year earlier in the case of Anderton v Ryan (1985). Consider how the doctrine of precedent would apply had the cases of Anderton v Ryan and R v Shivpuri been heard in each of the following situations and on the following dates instead of when they were actually heard: (i) Anderton v Ryan was decided by the House of Lords in 1950. Shivpuri comes before the House of Lords in 1951. (ii) Anderton v Ryan was decided by House of Lords in 1950. Shivpuri comes before the House of Lords in 1967. (iii) Anderton v Ryan was decided by the Court of Appeal in 1950. Shivpuri comes before the Court of Appeal in 2002. 45 Task D Explain which method of avoidance is most suited to each of the scenarios below. Illustrate your answer where appropriate: 1. The House of Lords wish to depart from a past decision of their own; 2. on appeal, the Court of Appeal disagrees with a ruling of the High Court and wishes to replace it with a different decision; 3. a judge in the Crown Court does not wish to follow a past precedent of a higher court as she feels that the facts are slightly different. [15] 46 Task E