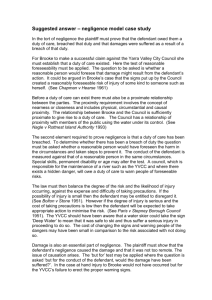

Negligence According to Winfield, Negligence as a tort is the breach

advertisement

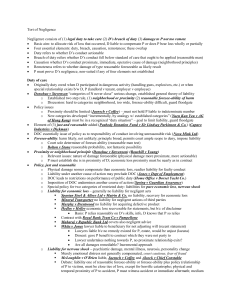

Negligence According to Winfield, Negligence as a tort is the breach of a legal duty to take care, which results in damage, undesired by D, to P. The 4 elements in Negligence (proved by P): ● Duty of care D owns him a duty of care ● Breach of duty D is in breach of duty ● Causation in fact P has suffered damage because of D’ breach ● Causation in Law Damage is not so remote 1) Duty of care ● The general principal ● Development: ● Pre-1932 - no general principal ● Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) ● The neighbour principal ● “You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour” ● Neighbours are persons who is closely and directly affected by my act that i ought reasonably to have them in contemplation (深思熟慮) as being so affected when i am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question. ● Anns v Merton Borough Council ● Developed the 2-stage test ● Stage 1: Sufficient Relationship of proximity between D and C ● ● Sage 2: Any policy consideration which could negative a duty Caused floodgates of cases ● Current Approach: Caparo v Dickman (1990) HL ● Facts: the claimants were considering a take-over bid for a company in which they held shares and, as shareholders, they received a copy of the company’s audited accounts. Acting in reliance on these accounts, which showed a profit made by the company, the claimants bought more shares in it and eventually took it over. It later emerged that due to the defendant auditors’ negligence, the accounts had been wrongly audited; the company had, in fact, made a loss. ● Held: The auditors’ statutory duty to prepare accounts was owed only to the shareholders as a body, to enable them to make informed decisions concerning the running of the company; the purpose of this duty, said their Lordships, was not to enable individual shareholders to buy shares with an eye on profits. ● In the case,their Lordship set out the three-stage test ● Stage 1: the damage must be reasonable foreseeable ● Stage 2: Sufficient proximity between the parties. ● Stage 3: Fair Just and Reasonable for the court to impose a duty of case in the light of policy considerations with which the court is concerned ● ● Further confirmed in Marc Rich v Bishop Rock Marine (1995) Duty of care is examined in two level ● Duty in Law Is there a duty at the abstract level: the court examines whether the law, in principle, recognizes liability for the type of damage inflicted, the general manner of its infliction, and the categories to which P and D belong. e.g. Nettleship v Weston (a driver owns a duty in law to other road user) ● Duty in Fact (i.e. whether P is foreseeable) whether specific D owned the specific P a duty to prevent the specific harm, inflicted in the specific manner ●COP: Palsgraf v Long Island Railroad ● Facts: Palsgraf was standing on a train platform preparing to get on the next train while two guards helped a man try to jump aboard a moving train. The guard, who was pushing the man on, didn’t notice as the package, wrapped in newspaper, the man was carrying fell to the tracks. They were fireworks and they went off, injuring plaintiff. ● ● No negligence COP: Bourhill v Young (HL, 1943) ● ✩ Facts: P who was pregant heard, but did not see, a crash caused by D’s motorcyclist's negligence. P later saw the aftermath of the accident an suffered nervious shock. ● Held: Failed because the harm to her of that type was not foreseeable. ● COP: Haley v London Electricity Board ● Facts: the defendant’s servants ‘roped off’ a hole they had been digging in the road, blocking the entrance by a single bar, near the ground, to protect pedestrians. Although rudimentary (早期), this was regarded (at that time!) as adequate protection for sighted pedestrians. The claimant, a blind man, fell into the hole and was injured. ● Held: Because the presence of blind persons was foreseeable, and adequate precautions for them would have been simple to take, the defendant was liable. ● ♪ Commentary: If safety measures are comparatively easy to take, the balance may weigh in favour (though not necessarily conclusively) of the claimant. Breach of duty ● The Standard of care ● Negligence defined in Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks: ●“Negligence is the omission to do something that a reasonable man would do or doing something which a reasonable would not do” (the Standard of Care) ● Special Rule apply to Expert Court likely considers the distinction between an activity which anyone is free to undertake and one which requires a licence or other qualification or certification. ● Phillips v William Whiteley ●Held: P who had her ears pierced by D, who were jewellers, could not expected them to exercise same degree of care and skill that would be exercised by a qualified surgeon. ● Nettleship v Weston ★★★ ● Lord Denning held that the standard of care required of a learner-driver is the same that of the ordinary driver. ● Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority ●Held: an inexperienced doctor is expected to observe the standard of a reasonably competent doctor of the relevant grade. The standard of care was said to be related to the job undertaken not to the individual’s experience. ● Guiding Factors ● Likelihood of risk of harm A ordinarily careful man does not take precautions against every foreseeable risk. ● COP: Bolton v Stone ● The House of Lords found that the risk of anyone outside a cricket ground being injured from within was so unlikely that the defendant was not liable in negligence. In other words, hits out of the ground were so rare, and the likelihood of a hit injuring someone so small that it was not a breach of duty to fail to erect extremely expensive fencing to eliminate the risk. ● Magnitude of harm Taking account magnitude of risk to individual ●COP: Paris v Stepney Borough Council (HoA) ● Facts: a one-eyed workman, engaged on work underneath vehicles, was blinded in his remaining eye by a metal splinter. ● Held: D were liable for failing to provide this particular work with goggles, knowing that he might suffer such serious consequences if the small risk materialised. ● Importance of D’s objective The greater the social utility of D’s conduct, the less likely it is that the D will be held to be negligent. ●COP: Watt v Hertfordshire C.C. (1954) ● Facts: a firemen, in a hurry to rescue a woman trapped under a vehicle, failed properly to secure a heavy jack (起重機) on the back of their lorry (the vehicle properly equipped for such a task being unavailable).The jack slipped and injured the claimant, one of the firemen. ● Held: the fire authorities had not been negligent because the need to act speedily in an attempt to save the woman’s life outweighed the risk to the P. Lord Denning indicated that the decision might have gone the other way had the defendants been engaged in ordinary commercial pursuits. ● ♪ Commentary: However the decision might not be followed today; health and safety at work has a higher priority, and professional rescuers are not expected to bear the consequences of this class of risk. ● Precautions which could be taken ●COP: Latimer v A.E.C ● Facts: the claimant was one of four thousand employees at the defendant’s factory; he slipped, at night, on the factory floor, the surface of which was oily. The floor had been flooded as the result of a very heavy thunderstorm, and when the flood subsided (退落) it left an oily film on the surface ● Held: The House of Lords held, overruling the trial judge, that it was not unreasonable for the defendants to put on the night-shift rather than close the factory until the oily surface had been rendered safe. In the circumstances there was insufficient evidence of want of :reasonable care. ● ♪ Commentary: It follows from this reasoning that danger caused by some fleeting, or temporary, or exceptional condition might not invoke liability; but each case must always be considered on its facts. ●Paris v Stepney Borough Council (HoA) ℒ: Assessing what is a reasonable standard of care is difficult. Perry v Harris (2008) where the court found at the first instance that parents were liable for an injury sustained by a child on a bouncy castle, where there had been inadequate supervision, but this decision was reversed by the HoL ● Related issues ● Common practice (Seriousness) Failure to conform (符合) to a common practice of taking safety precautions is strong evidence of negligence because it suggests that D did not do what others in the community regard as reasonable. ●Paris v Stepney Borough Council (HoA) ● A two-eyed employee doing the same job would not have needed the same protection, because the risks in general were not too high. Since the duty of employers was owed to each particular employee, D is liable despite the fact that he had acted in accordance with common practice. ● Professional Standard of care ●Opinion Divided (Professional) ● Principal in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) ● Where there is more than accepted method of doing things, both or all of which are regarded as proper by a skilled body of opinion, the judge is not entitled to make a finding of negligence on the basis of his preference for one method rather than another. (controversy) ●Professional Opinion Negligent ● COP: Bolitho v City and Hackney H.A. (1997) ● Facts: The doctor was summoned to attend a child with breathing difficulties but negligently failed to do so. If the doctor had come and had intubated (插管) the child it would probably have survived. The doctor claimed that had she attended she would have intubated and the outcome would therefore have been equally bad regardless of her breach of duty. ● Held: 1) HoL held that the doctor’s failure to intubate would not have been negligent, because her reasons for not doing so were supported by a body of responsible medical opinion. ● 2) However, HoL also made it clear that a doctor could be liable for negligent treatment or diagnosis despite a body of professional opinion supporting his conduct. The court had to be satisfied that the body of opinion was reasonable or responsible in that it could withstand logical analysis. ●Practice superseded ● Principal in ROE v Minister of Health (CA, 1954) ● An anaesthetist was not negligent in failing to appreciate the risk of percolation(過濾) of a preservative (預防藥) through invisible cracks in glass ampules (注射液瓶) in which the anaesthetic was stored, because such a danger was not known to exist at that time. ● Special standard of care ● Engaging in competition Competitors ●Principal in Wooldridge v Summer 1962 ● Facts: P was a photographer at a horse show. He was taking some close-up photographs at a horse-jumping event, when he was struck by a horse ridden by the defendant, who had, according to the claimant, been negligent in the handling of his steed. ● Held: 1) It was found that the defendant had not, in fact, been negligent, because he had kept within the rules of the competition and had observed the standard of care appropriate to a competitor in such an event. ● 2) CoA set a test for the sporting standard of care, sportsman only be liable if they had “acted in reckless (魯莽) disregard of the spectators’ safety” (subject to criticism) ●COP: Wilks v Cheltenham Cycle Club (CA 1971) ● Facts: A motor cycle scramble event, and a spectator was injured when one of the cycles got out of control. An action was brought in negligence against the organisers of the event and the motor cycle rider who had lost control. ● Held: 1) CoA held that there was negligence if injury was caused “by an error of judgement that a reasonable competitor, being the reasonable man of sporting world, would not have made” (a simpler ‘negligence’ approach) ● 2) A competitor going all out to win in such a competition could not be expected to observe the standard of care of a careful, prudent driver of an ordinary vehicle in use on the public highway. As the circumstances, D had observed the standard of care expected of him, within the rules of the event, and had not been negligent. ●COP: Condon v Basi ● Facts: A rugby tackle (扭倒) made in a reckless & dangerous manner ● Held: D’s serious and dangerous foul play which showed a reckless disregard of the plaintiff’s safety and which fell far below the standards which might reasonably be expected in anyone pursuing the game. Referees ●COP: Smoldon v Whitworth ● A referee who oversees a match may also owe a duty of care to see that players are not injured. Horseplay ●COP: Blake v Galloway ● The parties were engaged in high spirited horse game. The claimant threw at the defendant a piece of chipping bark which struck the defendant on his back. The defendant thereafter threw the chipping back towards the claimant and struck him just by the eyes causing substantial injuries. The claimant brought an action for battery and/or negligence. ● Held: D will be in breach of duty of care if his conduct amounts to recklessness or a very high degree of carelessness. However, its not the case. ● Old and Infirm (vulnerable) ● Principal in Daly v Liverpool corporation ●In deciding whether a 67 year old woman was guilty of contributory negligence in crossing a road one had to consider a woman of her age, not a hypothetical reasonable man. Since C still can walk quickly, D not liable. ● Children The conduct of a child defendant is judged by reference to the standard of conduct that can be expected of a reasonable child of D’s own age. ● Principal in Mullin v Richard ●Facts: P and D were 15 year old schoolgirls. They wee fencing with plastic rules during a lesson, when one of the ruler snapped (突然折斷) and a piece of plastic flew into P’s eye, causing blindness. ●D not liable. To prove if a child has been negligent, the objective standard of what a child might be reasonably expected to foresee is that of an ordinarily prudent and reasonable child of that age rather than that of a `reasonable man'. ● Duty to make allowances for other’s defect ● ● COP: Haley v London Electricity Board Emergencies Where D is forced to act quickly “in the heat of the moment”, the standard of care is relaxed to take account of the exigencies (緊急) of the situation. ● COP: Jones v Boyce (examine if C is in contributory negligent) ●Fact: a passenger jumped off in order to save himself, breaking his leg, when the coach was about to overturn. ●Held: the man was not in negligent, he just selected the more risky option with which he was confronted in an emergency. ℒ: The standard of care is held to be objective. However, its likely to be influenced largely by “what the judge thinks” despite reference to the man on the Clapham omnibus. General concerns which affect all our behaviour are weighted in the balance when assessing D’s conduct. Causation in fact ● Governed by the “but-for” test The claimant must prove that harm would not have occurred ‘but for’ (要不是) the negligence of the defendant. (Analogy “Would P’s loss have occurred in any case, even w/o D’s conduct”. If yes, D is not liable to C’s loss.) ● COP: “Barnett v Chelsea Hospital” (1968) ★★★ ●Fact: A man went to a casualty department feeling unwell after having drunk some tea. The doctor in charge him away w/o treatment, telling him to see his own doctor. He subsequently died from arsenic poisoning. ●Held: Though the doctor was in breach of duty of care in failing to examine the man, evidence indicated that, having drunk the arsenic (砒霜), the man was beyond help when he arrived at the hospital and would have died anyway. The doctor’s breach of duty had therefore not caused the man’s death. ● The court also considered the causal effect of hypothetical omission that might have produced the loss ●COP: Bolitho v City and Hackney H.A. (1997) ● Held: D who is breach of duty cannot escape liability by saying that damage would have occurred in any event because he would have committed some other breach of duty thereafter. (the point is not he would have done but is he should do) ● Multiple causes Where there are a number of possible causes of injury, the claimant must prove that the defendant’s breach of duty caused the harm or was a material contribution. ● COP: McGhee v National Coal Board (NCB) HL (1972) ●Facts: C had contracted dermatitis (皮膚炎) as a result of exposure to abrasive (磨蝕) dust at work. He claimed that they had been negligent or in breach of statutory duty in not installing showering facilities. This meant that he was exposed to the dust for longer. ●Held: P succeeded on the ground that it was sufficient to show that D’s breach materially increased the risk of injury, even though medical knowledge at the time was unable to establish the breach as the probable cause. ●Distinguished by Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority (1988) ● COP: Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority HL (1988) ●Facts: a premature baby was negligently give excessive oxygen. It is known that excessive oxygen given to premature babies can lead to blindness. But there were up to 5 possible cause of P’s blindness. ●Held: Adopted the all or nothing approach, holding that P had failed to establish, on the balance of probabilities, that his blindness had been produced by the excess oxygen, rather than by one of the five other possible common causes. ● COP: Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd HL (2002) ●Facts: the evidence showed more than 1 employer to have contributed to C’s inhalation of asbestos dust causing a form of cancer. Particular asbestos caused the disease, not due to continued exposure. ●Held: HoL allowed the appeal and held that if C is unable to prove, on the balance of probabilities,that D’s branch of duty was the cause of the disease, it was sufficient to prove that D materially increased the risk of harm. ● ♪ Commentary: HoL was prepared to relax the strict requirement of causation in order to produce what was perceived as a just result ● No damage for the loss of a chance ● COP: Hotson v East Berkshire Area Health Authority HL (1987) ●Facts: P suffered from an injured leg (an injury sustained in a non-tortious context) from which there was a chance of a full recovery. However, his leg was permanently damaged after negligent medical treatment for the injury and his chances of recovery were reduced to somewhere between 0 & 25%. ●Held: Reversing the decision of the Court of Appeal, that there is no principle in tort which would allow a percentage of a full financial recovery based on probabilities. His claim only be worked out if he can prove, on the balance of probabilities, that he would have recovered if given proper treatment, he was entitled to full compensation. Otherwise, he was entitled to nothings. COP: Gregg v Scott 2005 ●Facts: the misdiagnosis of the appellant’s medical condition by a medical practitioner had reduced his chances of surviving for more than 10 years from 41% to 25%. The judge dismissed his claim because the delay had not deprived him of the prospect of a cure; at the material time, the appellant had less than a 50% of surviving more than 10 years anyway. ●Held: Decision upheld in CoA and HoA that liability for loss of chance of a more favourable outcome should not be introduced into personal injury claims. ● But fully liable for failure to inform and give patient a choice ● COP: Chester v Afshar 2005 (a 3:2 majority decision) ●Facts: Following an elective surgical procedure on her spine, P suffered paralysis and brought an action against D (neurosurgeon) in negligence. The operation had not been negligently performed, the issue was one of causation as the C argued that she had no been given adequate warning of a 1-2% risk of paralysis (麻痹). Had she been aware of the risk she would not have consented to the operation taking place so soon and also, before deciding what to do, she would have sought a second or possibly even a third opinion. ●Held: Central to their Lordship’s reasoning was, for policy reason, doctor have duty to warn the patient about any significant risks involved in the treatment ●♪ Commentary: A relaxation of the “but for” test - D’s conduct, though not the proven cause of P’s loss, has probably increased the risk of P’s suffering such loss. It was not a case where D’s negligence had increased the risk that P would suffer loss. ● Multiple Tortfeasors (who commit a tort) Joint tortfeasors are jointly and severally responsible for the whole damage. ● COP: Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd HL (2002) ●All D are liable since each had negligently materially increased the risk of the contracting the disease satisfied the causal requirements for liability. (Affirmed MCGhee) ●The liability to pay compensation was to apportioned among the various D according to their relative degree of contribution to the risk of C contracting the disease. ● COP: Barker v Corus HL (2006) ●Facts: Exposure of asbestos on 3 separate occasion, but 1 of occasion is C himself worked as self-employed plasterer (石膏師). ●Held: HoL partially reversed the ruling in Fairchild and held that although D could still be liable w/o proof of causation, his liability only extended to the relative proportion to which the could have contributed to the chance of outcome ●Note: Section 3 of Compensation Act 2006: D can still be held jointly and severally liable for the damage where all have negligently exposed P to asbestos. ● Cases where successive acts cause damage ● COP: Baker v Willoughby ●Facts: the defendant negligently injured the claimant’s leg. He was later shot in that leg by X, the leg had to be amputated (切斷) and an artificial one fitted in its place. ●Held: P’s right of recovery was not limited to the loss suffered only before the date of the robbery, but that he was entitled to the damage that he would have received had there been no subsequent injury. (fully applied the “butfor” test, avoid P under-compensated) (In general, the courts make a deduction for the ‘vicissitudes of life’ - Risk of unrelated medical conditions occurring always taken into account when calculating damages for future loss of earnings. But the Court did not take this approach in the case) ● COP: Jobling v Associated Dairies Ltd ●Facts: D’s negligence caused a reduction in the P’s earning capacity. 3 yr later, before the trail, P was found to be suffering from a decrease, wholly unrelated to the original accident, which totally incapacitated (使無能力) him. ●Held: 1) D was found liable by the House of Lords only up to the point of P’s disablement. ●2) Their Lordship criticised the decision in Baker and pointed out that the aim of a damages award in tort is put P in the same position they would have been in had the tort not occurred. ●♪ Commentary: In Baker and Jobling there were supervening events (or causes) to consider and the court in each case was obviously of the opinion that justice and fairness would not be achieved were there to be a simple application of the test to the facts. It is clear that a more pragmatic and policy-based solution was the aim in these circumstances. Causation in Law (Remoteness of damage) D would not liable for every consequence of the breach of duty. As a matter of policy, some limits is placed on the extent of the consequence for which a person can be responsible. A person is liable for the reasonable foreseeable types of harm caused by the breach. ● Wagon Mound Test (Privy Council, 1961) - The Foreseeable Test ★★★ ● Facts: D negligently discharged into Sydney Harbour a large quantity of fuel oil which drifted (漂流) to P’s wharf where welding (焊接) in progress. P discontinued their operation, but later following an assurance that the oil was in no danger of igniting. A fire did eventually break out, however, causing damage to P’s wharf and to two ships upon which work was being done. ● Held: i. The occurrence of the fire was not reasonably foreseeable but it was reasonably foreseeable, of coz, that the oil might cause some damage to P’s wharf by fouling it. D not liable. ii. Re Polemis no longer a good law iii. Test for remoteness of damage was whether D could have reasonably foreseen the kind off damage for which P’s suing. (degree of foresight is generally irrelevant) ● Stewart v West African Terminals Ltd ● Principle: Lord Denning held that “It is not necessary that the precise (精確的) concatenation (串聯) of circumstances should be envisaged. If the consequence was one which was within the general range which any reasonable person might foresee (and was not of an entirely different kind which no one would anticipate) ” then it is within the rule that a person who has been guilty of negligence is liable for the consequences. ℒ: The reasonable man is not someone who can see what will happen in the future. He cant expected to see precisely how events will turns out as a result of a particular negligent act. Foreseeability of the “way the damage is caused” ● Hughes v Lord Advocate (liberal interpretation of Wagon Mount) ● Facts: Employee of the Post Office negligently left an open manhole (檢修孔) unattended in the street. It was covered by a canvas tent and surrounded by paraffin (煤油) warning lamps. Our of curiosity 2 young boys entered the tent and P, took one of lamps with him, then knocked into the hole and caused a violent explosion in which P suffered server burns ● Held: D liable. The precise manner in which the damage was caused did not have to reasonably foreseen. So long as D could reasonably foresee damage of relevant kind, (the burn) the damage would not be too remote. ● Lord Reid held that D can be liable even when the damage caused is greater in extent than was reasonably foreseeable. Only damage is different in “kind” can D escape liability ● Doughty v Turner (Conservative interpretation of Wagon Mount) ● Facts: Workman employed by D had allowed an asbestos cover to drop into a vat (大桶) of very hot liquid. The cover slid in at an angle and did not cause a splash (飛濺). However, chemical changes i the asbestos (unknown at the time) brought about by the high temperature caused an eruption (爆發)of the liquid, which splashed out of the vat, burning P. ● Held: D not liable. Distinguished Hughes on the basis that, the risk which materialised was very substantially different from any the could be foreseen. Foreseeability of the “kind of damage” ● Tremain v Pike (Conservative approach) ● Facts: P was a herdsman (牧人) employed by D, who were farmers. The farm became infested with rats and P contracted a rare disease by contact with rat’s urine. ● Held: Even if negligence had been proved, P could not succeed because although injury from rat bites or food contamination was foreseeable, this particular rare disease was entirely different in kind. ● Bradford v Robinson Rentals (liberal approach) ● Facts: P suffered frostbite (凍傷) when he was sent to journey by his employer in a van w/o heater. ● Held: Although frostbite was a rather unusual consequence in the circumstance, it was nevertheless “if the type and kind of injury which was foreseeable” ● Commentary: Currency tendency to adopt liberal approach. Foreseeability of the extent of the damage ● Vacwell Engineering v BDH Chemcials ● Principal: Applied what Lord Reid held in Hughes where D can be liable even when the damage caused is greater in extent than was reasonably foreseeable. Only damage is different in “kind” can D escape liability Facts: D manufactured and supplied a chemical that was liable to explode in contact with water but they gave no warning of this hazard to P. P’s employee placed a large quantity of the chemical in a sink whereupon an explosion of unforeseeable violence extensively damaged the premises. ● Held: Since the explosion and consequent damage were foreseeable, even though the magnitude and extend thereof were not, D held liable. Specific issue ● Intend consequence: Where D intends the consequence of his act, foreseeability is not an issue, and he will be liable. Where the actual consequences go beyond the intended consequences liability for the additional harm caused will be governed by foreseeability. ● Amount of Damage; According to the rule laid down in the Wagon Mound damages will be recoverable provided that the type of harm is reasonably foreseeable. It is not necessary for D to be able to predict the precise amount of damage that he causes. This is concerned with assessment of the amount of damages, rather than remoteness, therefore foreseeability is irrelevant e.g. provided personal injuries and loss of earning are a reasonably foreseeable consequence of D’s negligence, it does not matter whether P is the chairman of a public company or a farmer, the amount lost will be recoverable. (Full extent of damages recoverable provided the type of harm reasonably foreseeable. Eng-shell skull Principle Impose liability upon D for harm which is not only greater in extent than, but which is of an entirely different kind to, that which is foreseeable. Provided D could reasonably foresee some injury to a normal P, D would be labile for the full extend of the loss (even not to be foreseeable) ● Smith v Leech Brain 1962 ●Facts: A workman who had a predisposition to cancer received a burn on the lip from molten metal due to a colleague’s negligence ●Held: D liable for P’s eventual death from cancer triggered off by the burn. ● Plaintiff’s impecuniously (貧窮的) - the rule applies to the economic state of the victim in the same way as his physical and mental vulnerability ● Lagden v O’Connor 2003 ● Fact: D negligently drove the 10 year old car of P who did not have the financial resources to pay for a hire car while his car was off the road so he entered into a credit agreement which involved greater expense. ● Held: this additional expense was at least broadly foreseeable and, in stating that the wrongdoer must take his victim as he finds him. Break in the Chain of Causation - “Novus Actus Intereniens” Whether the damage is reasonably foreseeable in the sense of being a “natural and probable” result of D’s breach (ordinary D). A deliberate decision to do a positive act is more likely to break the chain than a mere omission; tortious/deliberate/negligence conduct is more likely to break the chain than a mere omission/mistake; 4 ● Third Party Interventions - any break in chain of factual causation or legal causation Negligent Intervention ● Knightley v Johns (1982) ●Facts: the 1st D, Johns, had caused an accident in a road tunnel within which operated a one-way traffic system. A police inspector, who was in charge of the situation, realised that he had failed to close the tunnel to oncoming traffic and ordered two constables (one of whom was the claimant) to go back against the oncoming traffic in the tunnel to remedy his mistake. The claimant was injured when he collided with a car; the motorist was not negligent. The claimant claimed damages from Johns, the police inspector and the chief constable ●Held: the inspector’s negligence in the present case was the real cause of the claimant’s injuries; it was a new cause and not a concurrent (併發的) cause with the negligence of Johns. It broke the chain of causation between the latter’s negligent act and the claimant’s injuries. Thus, the inspector and the chief constable were liable to the claimant. ● Rouse v Spuires (CA,1973) ●Fact: D, a lorry driver negligently caused an accident which blocked 2 lanes of highway. P,who was assisting at the scene, was killed when a second lorry driver negligently drove into obstruction. ●Held: D was 25% to blame. The negligent driving of the 2nd lorry driver did not break the chain of causation between the original accident & P’s dealth. A driver who caused an obstruction could be take reasonably to foresee that a further accident might be caused by other drivers negligently colliding with the obstruction. . ● Wright v Lodge (CA, 1993) ●Held: D’s negligence caused a lorry driver to collide with his car, as a result of which the lorry was involved in a further collision. It was found that the lorry driver had driven recklessly (not merely carelessly), and his driving was therefore held to be sole legal cause of the damage arising from the 2nd accident (liable to other road users when his vehicle overturned on the opposite side of the dual carriageway(車行道)) ●Principle: Whilst an act of negligent driving may not break the causation, then reckless driving may amount to a novus actus interveniens. . ● Haynes v Harwoord (CA, 1935) ●Principle: the act of a rescuer who goes to assist another put in peril (險境) by D’ negligence clearly is within the risk created by that negligence and is not therefore a novus actus Intentional acts of wrongdoing ● Lamb v Camden LBC (1983) [TB p.189-190] ●Held: an incursion of squatters (擅自佔用土地的人) is not one of the risks attendant upon undermining (漸漸破壞) the foundation of a building ●Principle: Suggesting that the nature of the relationship between D and the 3rd party is an important consideration of the Courts. ●♪ Commentary: Both relationship and degree of foreseeability play a part of the court’s reasoning, which are servants of the policy. ● P’s intervention P’s act will only break the chain of causation when it is unreasonable. ● McKew v Holland and Hannen (HL, 1969) ●Facts: Through D’s negligence P suffered an injury and for a short time afterwards he occasionally lost control of his leg. He went to inspect a flat and, without asking for assistance, he attempted to descend a steep flight of stairs with no handrail (扶手). When his leg gave way w/o warning he fell and sustained further injuries. ●Held: P’s unreasonable behaviour was a novus actus interveniens. He, not D, had caused his injury by descending the staircase without waiting for the assisting of his wife, knowing that his leg might give way (stop functioning) at any moment. ● Wieland v Cyril Lord Carpets Ltd (1969) ●Facts: P had been negligently injured and forced to wear a surgical collar (頸圈). This restricted her ability to focus her bi-focal glasses and as a result she sustained (承受) further injuries when she fell down some steps. (she already asked her son for accompany) ●Held: D were liable because P had not acted unreasonably in attempting to descend (下降) the steps. ● P’s suicide cases where D’s negligence creates a risk of psychiatric illness leading to suicide, the suicide does not constitute a novus actus interveniens. ● Pigney v Pointers Transport (1957) ●Held: Depressive mental illness which resulted from a negligently inflicted head injury had affected the deceased’s capability for rational judgement and his suicide was therefore held not to break the chain of causation. ● Corr v IBC Vehicles (2006) ●Facts: P suffered a head injury at work at work as a result of his employer negligence. He succumbed (failed to resist) to serve depression and eventually killed himself. ●Held: His suicide did not break the chain of causation. suicide is merely the culmination (頂點) of the depression. ● Reeves v Metropolitan Police Commissioner MPC (1999) ●Facts: The deceased, who was in police custody,had made 2 previous attempts to kill himself whilst in custody. Although dr who examined the deceased uopn his arrival at the police station found no evidence of psychiatric illness, dr gave instructions that he was a suicide risk and should be frequently obseved. The deceased was checked by an officer who inadvertently (不注意地) left wicket (小門) hatch in his cell door open, and shortly afterwards the deceased was found to have hanged himself by tying his shirt through the open wicket. D conceded (admit) that they owned the deceased a duty of care but denied liability on the basis that his own suicide was a novus actus interveniens breaking the chain of causation ●Held: D knew the the deceased was a suicide risk, his suicide was not a new act but the very harm they were under a duty to try to prevent. However, their Lordship also found that deceased bore at least partial responsibility for his death, and damages were consequently reduced by 50%. Unusual case Meah v McCreamer (1985) The claimant sustained head injuries in an accident caused by the defendant’s negligent driving. As a result, he underwent a marked personality change and subsequently committed crimes of violence against several women. Prior to the accident he had had a history of petty crime and a poor employment record, but he had had a number of relationships with women and there was no evidence of his being violent towards them. The claimant argued that without the accident he would not have committed these offences because there would have been no personality change. There was medical evidence to the effect that the claimant was in any event a ‘criminally aggressive psychopath’ and that he was someone who had ‘underlying tendencies to sexual aggressiveness’, but the judge regarded him as a person who was not committed to violent crime prior to his accident; it was due to the accident that his inhibitions had been reduced and he had given vent to his feelings. He was awarded damages for his imprisonment, subject to a discount for his free board and his poor employment record; and for his criminal tendencies, which would probably have resulted in him spending some periods in prison. His damages were also reduced for his contributory negligence in accepting a lift from the defendant, knowing him to be drunk at the time.The claimant was later sued in trespass to the person, successfully, by two of the women he had attacked (unforeseeable P), and in the 1986 proceedings he claimed from the defendant these amounts of money. This claim was unsuccessful, being too remote; it would also be contrary to public policy, said the judge, to allow such a claim. ● Clunis v Camden & Islington Health Authority (1998) Held: A mental patient released into the community is not owed a duty of care in negligence by the Health Authority. Disapproved Meah. Res Ipsa Loquitur (the facts speak for themselves) Where the maxim applied, the court is prepared to draw an inference that D has been negligent w/o requiring C to bring evidence about the precise way in which the negligence occured. ● Scott v London & St. Katherine Docks ✭ ●Facts: P was passing D’s warehouse when 6 bags of sugar, which were being hoisted (吊起) by D’ crane, feel on him. P could not prove how and why this happened. - the only thing he could prove was that the bags feel and cuased him injury. ●Held: These facts were sufficient to give rise to an inference (推論) of negligence. Bags of sugar do not usually fall from a crane unless someone has been negligent, so the fact of negligence “spoke for itself”. Since D had failed to provide an innocent explanation of how the incident had occurred,they were held liable. Liability in road traffic accident ●J v North Lincolnshire C.C. ● Facts: 10 year old with learning difficulties left school premises and was injured by car ● Held: The maxim are applied. The circumstances of the child getting on to the road called for an explanation by D, which was consistent with their having taken proper care and this would be fatally (不幸地) undermined (暗地裡破壞) if they were able to throw the issue of causation on to C. Effect of the maxim: ●Ng Chun Pio v Lee Cheun Tat (TB p166) ● Burden of proving negligence rests throughout the case on P. Requirement for Res Ipsa Loquitur applies 1.The occurrence must be one that will not normally happen w/o negligence ● Ward v Tesco Stores Ltd ● Negligence inferred when P slipped on a spillage of yoghurt on a supermarket floor, which D had failed to clean up. 2.D must have control of the things which causes the harm ● Gee v Metropolitan Railway ● P was injured when he fell out of the train leaving the station. Clearly D had the duty to see the the door was close before the train departed ● By contrast, Easson v LNER ● P fell out of train 7 miles out of last station. the maxim not applied, it was not appropriate to infer that it was, because the door might have been opened by a passenger, rather than 1 of D’s employee. 3.The cause of occurrence must be unknown to claimant ● Bolton v Stones ● The maxim are not applied since the cricket ball must have been hit over the fence (柵欄) by the batsman (擊球手) . Defences ● Contributory Negligence “Where any person suffers damage as the result partly of his own fault and partly of the fault of any other person(s), a claim in respect of that damage shall not be defeated by reason of the fault of the person suffering the damage, but the damage recoverable in respect thereof shall be reduced to such extent as the courts thinks just and equitable having regard to the P’s share in the responsibility for the damage.” [Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945] (just quote 1-2 example) P acted negligently? ● Jones v Livox Quarries ●Lord Denning: “A persona is guilty of CR if he ought reasonably to have foreseen that, if he did not act as reasonable, prudent man, he might hurt himself; and his reckonings; he must take into account the possibility of others being careless ” ●♪ Commentary: Objective tests, allowances made for children, aged & infirm ●Jones v Boyce (1816) ● Principal: it was a question of whether of P acted reasonably & allowance should made for decision taken in the “heat of moment”/emergency (which is due to the fault of D) P’s action contribute to the damage suffered ● Stapley v Gypsum Mines Ltd ●Facts: P had been killed in a mining accident when a large piece of the roof fell upon him. He and his colleagues, had been instructed earlier to make the part of mine safe. They tried unsuccessfully to bring down the roof & then carried working. ●Held: Damage reduced to 80% for CR. ●Lord Reid foudn the Q of who had contributed to the damage to be one of common sense, and a generally a matter of court’s discretion, depending on the facts of each cases, ● Froom v Butcher ●Held: P’s failure to wear seat belt did amount to CR. It had added to the injury suffered & it was irrelevant that P believed that it would be safer not to wear a seat belt. Damage reduced by 20%. ●The court also gave general guidance for damage reduction for not wearing a seat belt: ● 25% if injury would have been prevented; ● 15% if injury would have been less severe ● 0% if wearing seat belt would not have prevented injury Children Age is crucial factor ● Yachuk v Oliver Blais Co Ltd (1949) ●Facts: D supplied a 9 year old with a pint of petrol. He had falsely stated that his mother wanted the petrol for her car. When he used the fuel to make a burning torch for the purpose of a game he suffered severe injury. ●Held: D was liable in negligence for supplying the petrol. The boy had not been guilty of CR for he neither knew nor could be expected to know of the danger. ● Gough v Thorne (1966) ●Facts: P, 13 year old, was waiting to cross the road. She was beckoned (招手示意) to proceed by the driver of lorry & as she did so she was struck by D who was driving too fast. ●Held: Her relying on driver’s signal did not constitute to CR. Lording Denning held that “A very young children cant be guilty of CR”‘ Elderly Reasonable act of her/his age ● Daly v Liverpool Corporation No 100% CR ● Pitts v Hunt ●It is not possible to making a finding of 100% CR under the 1945 Act as the act contemplates (深思熟慮) D being at least partly to blame. Volenti non fit injuria (rarely successfuA person who expressly or impliedly agrees with another to run the risk of harm created by that, other cant thereafter sue in respect of damage suffered as a result of the materialisation of that risk. If successful, is complete bar to recovery. l today since the CR in Law Reform Act) ●Smith v Charles Baker & Son 1891 ● Held: Volenti was rejected; even though P had knowledge of the danger & continued to work (he complaint to D about the danger), he had not voluntarily undertaken the risk. Car passengers A passenger who accepts a lift with a driver who, to his knowledge, is inexperienced or drunk, cannot be held volenti to the risk, because S 149 Road Traffic Act 1988 prohibits any restriction on the driver’s liability to his passenger as is (照現在的樣子) required to be covered by insurance.