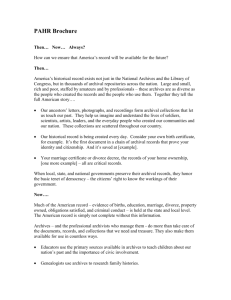

managing public sector records

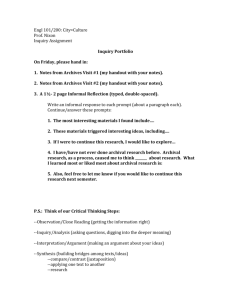

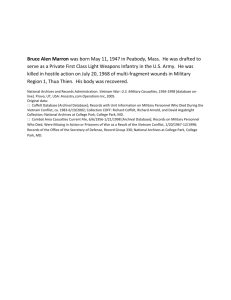

advertisement