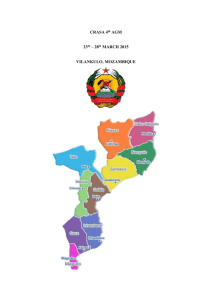

1 - tipmoz

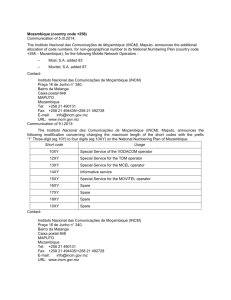

advertisement