DECISION MAKING IN ORGANIZATIONS

advertisement

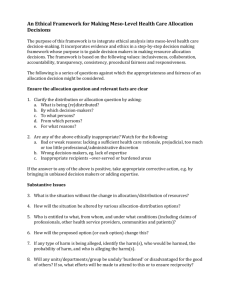

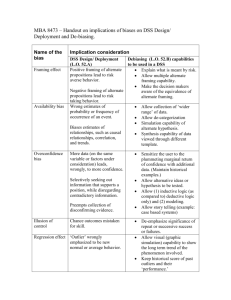

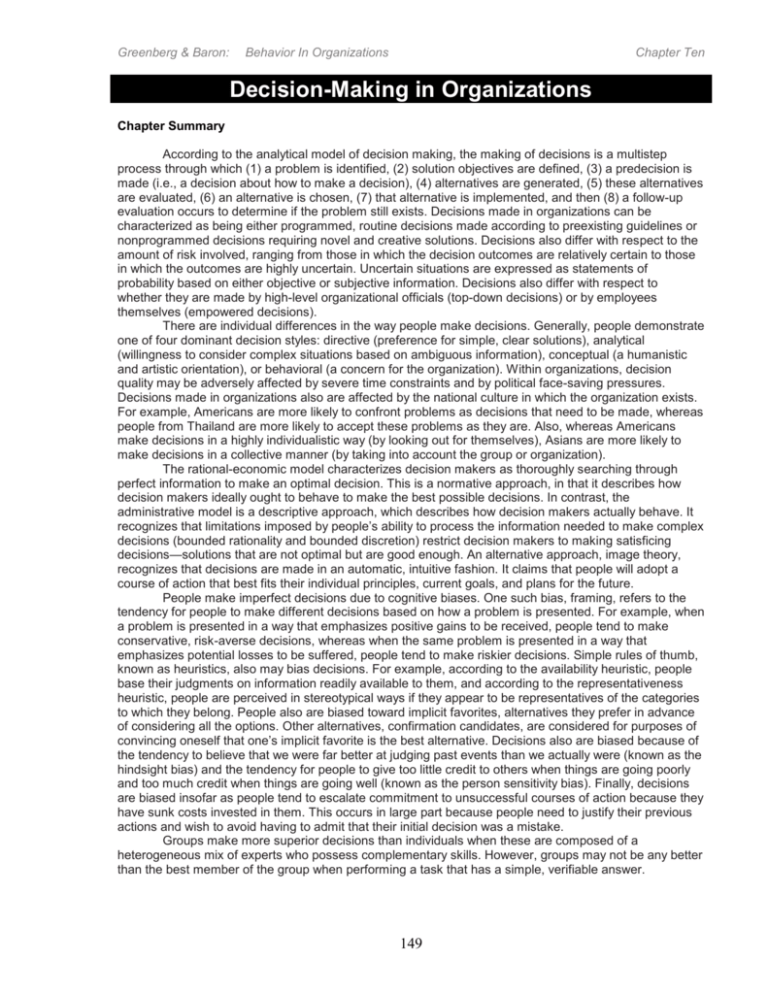

Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Decision-Making in Organizations Chapter Summary According to the analytical model of decision making, the making of decisions is a multistep process through which (1) a problem is identified, (2) solution objectives are defined, (3) a predecision is made (i.e., a decision about how to make a decision), (4) alternatives are generated, (5) these alternatives are evaluated, (6) an alternative is chosen, (7) that alternative is implemented, and then (8) a follow-up evaluation occurs to determine if the problem still exists. Decisions made in organizations can be characterized as being either programmed, routine decisions made according to preexisting guidelines or nonprogrammed decisions requiring novel and creative solutions. Decisions also differ with respect to the amount of risk involved, ranging from those in which the decision outcomes are relatively certain to those in which the outcomes are highly uncertain. Uncertain situations are expressed as statements of probability based on either objective or subjective information. Decisions also differ with respect to whether they are made by high-level organizational officials (top-down decisions) or by employees themselves (empowered decisions). There are individual differences in the way people make decisions. Generally, people demonstrate one of four dominant decision styles: directive (preference for simple, clear solutions), analytical (willingness to consider complex situations based on ambiguous information), conceptual (a humanistic and artistic orientation), or behavioral (a concern for the organization). Within organizations, decision quality may be adversely affected by severe time constraints and by political face-saving pressures. Decisions made in organizations also are affected by the national culture in which the organization exists. For example, Americans are more likely to confront problems as decisions that need to be made, whereas people from Thailand are more likely to accept these problems as they are. Also, whereas Americans make decisions in a highly individualistic way (by looking out for themselves), Asians are more likely to make decisions in a collective manner (by taking into account the group or organization). The rational-economic model characterizes decision makers as thoroughly searching through perfect information to make an optimal decision. This is a normative approach, in that it describes how decision makers ideally ought to behave to make the best possible decisions. In contrast, the administrative model is a descriptive approach, which describes how decision makers actually behave. It recognizes that limitations imposed by people’s ability to process the information needed to make complex decisions (bounded rationality and bounded discretion) restrict decision makers to making satisficing decisions—solutions that are not optimal but are good enough. An alternative approach, image theory, recognizes that decisions are made in an automatic, intuitive fashion. It claims that people will adopt a course of action that best fits their individual principles, current goals, and plans for the future. People make imperfect decisions due to cognitive biases. One such bias, framing, refers to the tendency for people to make different decisions based on how a problem is presented. For example, when a problem is presented in a way that emphasizes positive gains to be received, people tend to make conservative, risk-averse decisions, whereas when the same problem is presented in a way that emphasizes potential losses to be suffered, people tend to make riskier decisions. Simple rules of thumb, known as heuristics, also may bias decisions. For example, according to the availability heuristic, people base their judgments on information readily available to them, and according to the representativeness heuristic, people are perceived in stereotypical ways if they appear to be representatives of the categories to which they belong. People also are biased toward implicit favorites, alternatives they prefer in advance of considering all the options. Other alternatives, confirmation candidates, are considered for purposes of convincing oneself that one’s implicit favorite is the best alternative. Decisions also are biased because of the tendency to believe that we were far better at judging past events than we actually were (known as the hindsight bias) and the tendency for people to give too little credit to others when things are going poorly and too much credit when things are going well (known as the person sensitivity bias). Finally, decisions are biased insofar as people tend to escalate commitment to unsuccessful courses of action because they have sunk costs invested in them. This occurs in large part because people need to justify their previous actions and wish to avoid having to admit that their initial decision was a mistake. Groups make more superior decisions than individuals when these are composed of a heterogeneous mix of experts who possess complementary skills. However, groups may not be any better than the best member of the group when performing a task that has a simple, verifiable answer. 149 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Individuals make more superior decisions than face-to-face brainstorming groups on creative problems. However, when brainstorming is done electronically—that is, by using computer terminals to send messages—the quality of decisions tends to improve. Decision quality may be enhanced in several different ways. First, the quality of individual decisions has been shown to improve following individual training in problem solving skills. Training in ethics also can help people make more ethical decisions. Group decisions may be improved in three ways. First, in the Delphi technique, the judgments of experts are systematically gathered and used to form a single joint decision. Second, in the nominal group technique, group meetings are structured so as to elicit and evaluate systematically the opinions of all members. Third, in the stepladder technique, new individuals are added to decision-making groups one at a time, requiring the presentation and discussion of new ideas. Contemporary techniques also employ the use of computers as aids in decision making. One of these is known as electronic meetings. These are computer networks that bring individuals from different locations together for a meeting via telephone or satellite transmissions, either on television monitors or via shared space on a computer screen. Another computer-based approach is computerassisted communication—the sharing of information, such as text messages and data relevant to the decision, over computer networks. Finally, computers have been used to facilitate decision making by way of group decision support systems. These are interactive computer-based systems that combine communication, computer, and decision technologies to improve the effectiveness of group problem solving meetings. Learning Objectives 1. Identify the steps in the analytical model of decision making and distinguish between the various types of decisions that people make. 2. Describe different individual decision styles and the various organizational and cultural factors that influence the decision-making process. 3. Distinguish among three approaches to how decisions are made: the rational-economic model, the administrative model, and image theory. 4. Identify the various factors that lead people to make imperfect decisions. 5. Compare the conditions under which groups make more superior decisions than individuals and when individuals make more superior decisions than groups. 6. Describe various traditional techniques and high-tech techniques that can be used to enhance the quality of individual decisions and group decisions. Lesson Planning At the end of every chapter are a variety of questions pertaining to the learning objectives which can be used any number of ways to reinforce your presentation of the material. Ideas include using the questions to lead a class discussion, breaking students into small groups and giving them a question to respond to (“buzz groups”), assigning them for homework, or using at the end of class in an evaluative manner by choosing one for students to respond to in a timed writing for just a minute or two (one-minute essay). If you choose to use the one minute essay format—don’t use it for a grade for the student—but as a feedback mechanism for yourself to evaluate what the students learned. Also at the end of the chapter are exercises for individuals and groups. Web surfing exercises are also included to allow you to introduce e-learning applications to your lessons. They can be done outside of class for homework/group projects, or you might try using them as a demonstration if you have internet access in your classroom. Additionally, the class could meet in the computer lab where they can work on them together. Other exercises include a practice exercise to give students an opportunity to apply their new knowledge and a case study with critical thinking questions. Each of the exercises found in the text is noted within shadowed boxes throughout the lecture outline which follows. Remind students to bring their text to every class so that they will be able to reference the material if you choose to include an exercise in your presentation. There is far more material included here than can be accomplished in an average undergraduate class—but the goal was to provide you choices so that your can offer your students a variety of learning experiences. Suggested answers for the case study’s critical thinking questions and other review questions can be found at the end of these chapter notes. 150 Greenberg & Baron: I. Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten THE NATURE OF DECISION MAKING Notes A. A GENERAL, ANALYTICAL MODEL OF THE DECISIONMAKING PROCESS 1. Traditionally, the decision-making process is conceptualized as a series of analytical steps that groups or individuals take to solve problems. 2. The general model of this process--the analytical model of decision making can help us to understand the complex nature of organizational decision making. 3. The two key aspects of making decisions are formulation-the process of understanding a problem and making a decision about it; and implementation--the process of carrying out that decision. 4. The model’s first step is problem identification. a. What is it that we are trying to address? b. People do not always perceive social situations accurately. c. How we see a problem determines how we try to solve it. 5. The next step is to define the objectives to be met in solving the problem. a. It is important to conceive of problems in a way that allows possible solutions to be identified. 6. The third step is to make a predecision. a. A decision about how to make a decision. b. By assessing the type of problem identified as well as other aspects of the situation, managers may opt to make a decision themselves, to delegate the decision to another, or to have a group make the decision. c. Recently computer programs have been developed that summarize much of this information and, thereby, give managers ready access to a wealth of social science information that may help with predecisions. d. Such decision support systems (DSS), are only as good as the social science information that goes into developing them, but DSS techniques are effective in helping people to make decisions about solving problems. 7. The fourth step in the process is alternative generation, in which possible solutions are identified. When coming up with solutions, people tend to rely on previously used approaches that might provide ready-made answers. 8. The fifth step is evaluating alternative solutions. Some alternatives may be more effective than others, and some may be more difficult to implement than others. 151 Figure 10.1 p.359 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes 9. In the sixth step, a choice is made. Choosing a course of action is the step that most often comes to mind when we think about the decision-making process. 10. The seventh step calls for implementation of the chosen alternative. In other words, the chosen alternative is performed. 11. The final step is follow-up. Monitoring the effectiveness of decisions put into action is important to the success of organizations. 12. It is important to reiterate this is a very general model of the decision-making process. It may not be followed exactly as specified in all circumstances. B. THE BROAD SPECTRUM OF ORGANIZATIONAL DECISIONS 1. We now distinguish between decisions in three important ways: how routine they are, how much risk is involved, and who in the organization makes them. Programmed and nonprogrammed decisions. 2. A decision that is made repeatedly and according to a preestablished set of alternatives is a programmed decisions, routine decisions by lower-level personnel that rely on predetermined courses of action. Table 10.1 p.362 Table 10.2 p.363 3. In contrast, nonprogrammed decisions, ones for which no ready-made solutions exist. In these cases, the decisionmaker confronts a unique situation, and the solutions are equally novel. 4. Certain types of nonprogrammed decisions are known as strategic decisions. a. These decisions are made by coalitions of high-level executives and have important, long-term implications for the organization. b. Strategic decisions reflect a consistent pattern for directing the organization in some specified fashion, according to an underlying organizational philosophy or mission. Certain and uncertain decisions. 5. Degrees of certainty and uncertainty are expressed as statements of risk. 6. All organizational decisions involve some degree of risk, which ranges from complete certainty (i.e., no risk) to complete uncertainty or “a stab in the dark” (i.e., high risk). 7. What makes a decision risky is the probability of obtaining the desired outcome. 152 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten 8. Decision-makers try to obtain information about the probabilities (or odds) of certain events occurring given that other events have occurred. a. Day be considered to be reports of objective probabilities, when they are based on concrete and verifiable data. b. Many decisions also are based subjective probabilities, personal beliefs or hunches about what will happen. 9. Uncertainty is an undesirable in decision-making situations. Decision uncertainty can be reduced by establishing linkages with other organizations. The more an organization knows about what another will do, the greater certainty it has in making decisions. 10. What reduces uncertainty in decision-making is information. Knowledge about the past and the present can help when making projections about the future. 11. A variety of on-line information services now provide organizational decision-makers with the latest information relevant to the decisions they are making. 12. Many managerial decisions also are based on the decisionmaker s past experiences and intuition. When making decisions, people often rely on what has worked for them in the past. 13. This works because experienced decision-makers tend to make better use of information relevant to the decisions they are making. 14. Individuals with expertise in certain subjects know what information is most relevant as well as how to interpret that information to make the best decisions. Top-down and empowered decision. 15. Traditionally, making decisions in organizations was a manager’s job. a. Subordinates collect information and give it to their superiors, who then use it to make decisions. b. Known as top-down decision making, this approach puts the power to make decisions in the hands of managers. 16. Today the idea of empowered decision making allows employees to make the decisions required to do their jobs without seeking supervisory approval. 17. The rationale is that the people who actually do the jobs know best, so having someone else make the decision may not make the most sense. In addition, when people are empowered to make their own decisions, they are more likely to accept the consequences of them. 153 Notes Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes II. FACTORS AFFECTING DECISIONS IN ORGANIZATIONS A. DECISION STYLE: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN DECISION MAKING 1. There are meaningful differences between people in their orientation toward decisions, in their decision style. The decision-style model classifies four major decision style. 2. The directive style characterizes people who prefer simple, clear solutions. Individuals with this style tend to make decisions rapidly, using little information, relying on existing rules, and they aggressively use their status to achieve results. 3. Individuals with the analytical style are more willing to consider complex solutions based on ambiguous information. People with this style tend to analyze their decisions carefully, use as much data as possible, enjoy solving problems, and they want the best possible answers. 4. Compared to people with the directive or the analytical style, people with the conceptual style tend to be more socially oriented in their approach to problems. Their approach is humanistic and artistic, they consider many broad alternatives, solve problems creatively, and they have a strong future orientation. 5. Individuals with the behavioral style have a deep concern for the organizations in which they work and for the personal development of their coworkers. They are highly supportive of others and concerned about others’ achievements, and they frequently help others to meet their goals. Such individuals are open to suggestions from others and, therefore, tend to rely on meetings for making decisions. 6. Although most managers may have one dominant style, they often use many different styles. Those who can shift between styles--that is, those who are most flexible in their approach to decision making--have highly complex, individualistic styles of their own. 7. Conflicts often occur between individuals with different styles. Being aware of people’s decision styles is a potentially useful way of understanding social interactions in organizations. 8. Scientists have developed the decision-style inventory, which is a questionnaire designed to reveal the relative strength of people’s decision styles. 9. Research using the decision-style inventory revealed that A sample of corporate presidents had approximately equal scores in each of the four categories. 10. Military leaders tend to have high scores on conceptual style and people oriented approach. 154 Figure 10.3 p.366 OB In An E-World: Adaptive Agents As Decision Aids p.366 Individual Exercise: What Is Your Personal Decision Style? p.398 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes 11. People take very different approaches to the decisions they make. Coupled with their interpersonal skills, their personalities lead them to approach decisions in consistently different ways. B. GROUP INFLUENCES: A MATTER OF TRADE-OFFS 1. Potential benefits of decision-making groups. a. First, bringing people together may increase the amount of knowledge and information available for making good decisions. b. A related benefit is the specialization of labor. c. Another benefit is that group decisions are likely to enjoy greater acceptance than individual decisions. 2. Potential problems of decision-making groups a. One obvious drawback is that groups are likely to waste time. b. Another problem is that potential disagreement over important matters may breed ill will and group conflict. c. Finally, groups sometimes may be ineffective because of members’ intimidation by group leaders. 3. Groupthink: too much cohesiveness can be a dangerous thing. a. Sometimes group members become so concerned about not rocking the boat that they become reluctant to challenge the group’s decisions. b. Space shuttle Challenger tragedy in January 1986 is an example of the consequences of group think. . 4. Groupthink occurs in governmental decision making, but it also occurs in the private sector although in such cases, the failures may be less well publicized. C. ORGANIZATIONAL BARRIERS TO EFFECTIVE DECISIONS 1. There are several organizational factors that also interfere with making rational decisions. One obvious factor is time constraints. 2. Many important organizational decisions are made under severe time pressure, and under such circumstances, it often is impossible for exhaustive decision making to occur. 3. The quality of many organizational decisions also may be limited by political “face-saving” pressure. People may make decisions that help them to look good to others, even though the resulting decisions might not be in the best interest of their organizations. 4. One study of political face-saving found that businesspeople working on a group decision-making problem opted for an adequate--but less-than-optimal-decision rather than risk generating serious conflicts with their fellow group members. 155 Figure 10.4 p.369 How To Do It: Strategies For Avoiding Groupthink p.370 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten D. CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN DECISION MAKING 1. Even if people followed the same basic steps when making decisions, there would still be widespread differences in the way people from various cultures might go about doing so. 2. Thailand, Indonesia, or Malaysia, however, managers often accept nonperformance by suppliers as fate and allow the projects to be delayed. 3. An American, Canadian, or Western European manager, perceived such a situation as a problem in need of a decision, whereas Thai, Indonesian, or Malaysian managers perceive no such problem. 4. Cultures also differ regarding the nature of the decisionmaking unit they typically employ. a. In the United States, where people tend to be highly individualist, individual decisions are common. b. In more collectivist cultures such as Japan, however, it is inconceivable for someone to make a decision without first gaining the acceptance of his/her immediate colleagues. c. Swedes may totally ignore an organizational hierarchy and contact whomever is needed to make a decision, however high-ranking that individual may be. d. In India, however, where autocratic decision making is expected, a manager consulting a subordinate about a decision is considered to be a sign of weakness. 5. Yet another cultural difference deals with time. a. In the United States, one mark of a good decision maker is decisive, willing to make an important decision without delay. b. In Egypt, the more important the matter, the more time the decision-maker is expected to take. E. TIME PRESSURE: MAKING DECISION IN EMERGENCIES 1. The rapid pace of business, and the urgency of occupations such as police and firefighters and emergency workers often allows only a limited time for making decisions. 2. Highly experienced experts are able to make good decisions because of the wealth of experience they have gained over the years—often referred to as “gut instinct.” 3. For those who are not yet experts—try the following: a. Recognize your prime objectives: Learn the rules of your organization and rely on them when making decisions. b. Rely on experts: Look within your organization for assistance. c. Anticipate crises: Prepare for situations by practicing in advance. d. Learn from mistakes: Think of each one as training for the next time a decision needs to be made. 156 Notes Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten III. HOW ARE INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS MADE? Notes A. THE RATIONAL-ECONOMIC MODEL: IN SEARCH OF THE IDEAL DECISION 1. Organizational scientists view rational decisions as being ones that maximize the attainment of goals. 2. Economists interested in predicting market conditions and prices have relied on a rational-economic model of decision making that assumes decisions are optimal in every way. 3. Thus, an economically rational decision-maker attempts to maximize his/her profits by systematically searching for the optimal solution to a problem. 4. The decision-maker must have complete and perfect information and then process it in an accurate and unbiased fashion. 5. In many respects, rational-economic decisions follow the same steps outlined in the analytical model of decision making. 6. What makes the economic approach special is that it calls for decision-makers to recognize all alternative courses of action and to evaluate each one accurately and completely. This approach views decision-makers as attempting to make optimal decisions. 7. The rational-economic approach does not fully appreciate human fallibility. This model can be considered a normative (or prescriptive) approach, one describing how decision-makers ideally should behave to make the best possible decisions. B. THE ADMINISTRATIVE MODEL: THE LIMITS OF HUMAN RATIONALITY 1. People generally do not act in a completely rationaleconomic manner. 2. The administrative model, recognizes decision-makers may have a limited view of the problems confronting them. 3. The number of solutions that can be recognized or implemented is limited by the capabilities of the decisionmaker, by the available resources, and decision-makers do not have perfect information about the consequences of their decisions. 4. Instead of considering all possible solutions, decisionmakers consider solutions as they become available, and they decide on the first alternative that meets their criteria. a. Thus, the decision-maker selects a solution that may be good enough, but not optimal. b. Such decisions are referred to as satisficing decisions. 157 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes 5. In most decision-making situations, satisficing decisions are acceptable and more likely to be made than optimal ones. The model recognizes the bounded rationality under which most organizational decision-makers operate. 6. People lack the cognitive skills required to formulate and solve highly complex business problems in a completely objective, rational way. 7. Decision-makers limit their actions to those falling within the bounds of current moral and ethical standards, they use bounded discretion. 8. The administrative model is descriptive (or proscriptive) in nature. It describes how decision makers actually behave rather than specifying an ideal. C. IMAGE THEORY: AN INTUITIVE APPROACH TO DECISION MAKING 1. Selecting the best alternative by weighing all options is not always a major concern when making a decision. People also consider how various alternatives fit with their persona] standards, goals, and plans. 2. People may make decisions in a more automatic, intuitive fashion than traditionally is recognized. Representative of this approach is Image Theory. 3. Image theory deals primarily with decisions about adopting a certain course of action or changing a current course of action. In the theory, people make adoption decisions based on a simple, two-step process. 4. The first step is the compatibility test, which is a comparison of the degree to which a particular course of action is consistent with various images, particularly individual principles, current goals, and future plans. a. If any lack of compatibility exists regarding these considerations, a rejection decision is made. b. The decision then is made to accept the best candidate by comparing the various alternatives that best fit the decision maker’s values, goals, and plans. 5. These tests are used within a certain decision frame, with consideration of meaningful information about the context of the decision. 6. According to image theory, the decision making process is both rapid and simple. People do not ponder decisions but make them using a smooth, intuitive process with minimal cognitive processing. 7. Recent research also suggests that when making relatively simple decisions, people do tend to behave as suggested by image theory. 158 Figure 10.6 p.375 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten IV. IMPERFECTIONS IN INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS Notes A. FRAMING EFFECTS 1. Framing is the tendency for people to make different decisions based on how the problem is presented to them. 2. Scientists have identified three different forms of framing effects that occur when people make decisions: 3. Risky choice frames: a. When problems are framed in a manner emphasizing the positive gains to be received, people tend to shy away from taking risks and go for the sure thing (i.e., decision-makers are said to be risk-averse). b. When problems are framed in a manner emphasizing the potential losses to be suffered, however, people are more willing to take risk to avoid those losses (i.e., decision-makers are said to make risk-seeking decisions). 4. Attribute framing: a. Risky choice frames involve making decisions about a course of action. The same basic idea, however, applies to situations not involving risk but involving evaluations. b. Attribute framing effect occurs in many organizational settings, people evaluate the same characteristic more positively when it is described positively than when it is described negatively. 5. Goal framing: a. Goal framing--focuses on one important question. b. When persuading someone to do something, is it more effective to focus on the positive consequences of doing it or on the negative consequences of not doing it. c. A general note about framing: The kinds of framing described here, though similar in several ways, also are quite different. They focus on different types of behavior, preferences for risk, evaluations of characteristics, and taking behavioral action. B. RELIANCE ON HEURISTICS 1. Heuristics are simple decision rules used to make quick decisions about complex problems. 2. The availability heuristic refers to the tendency for people to base their judgments on readily available information--even though that information might not be accurate. 3. Basing judgments solely on conveniently available information increases the possibility of inaccurate decisions, yet the availability heuristic often is used. 159 Figure 10.7 p.377 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten 4. The representativeness heuristic refers to the tendency to perceive others in stereotypical ways if they appear to be “typical” representatives of their category. Research has found that people tend to make this type of error. 5. Heuristics do not always deteriorate the quality of decisions. People often them to help simplify the complex decisions they face. 6. However, the representativeness heuristic and the availability heuristic, however, may be recognized as impeding to superior decisions, because they discourage people from collecting and processing as much information as they should. V. THE INHERENTLY BIASED NATURE OF INDIVIDUAL DECISIONS A. BIAS TOWARD IMPLICIT FAVORITES 1. Implicit favorite: One’s preferred decisions alternative, selected even before all options have been considered. 2. Research suggests people that people tend to pick an implicit favorite option (i.e., a preferred alternative) early in the decision-making process. Subsequent options are not given serious consideration. They are used merely to convince oneself the implicit favorite is indeed the best choice. 3. In one study of the job recruitment process, investigators found they could predict 87 percent of the jobs that students would take as early as 2 months before the students actually acknowledged they had made a decision. 4. People’s decisions are biased by their tendency not to consider all the available relevant information. They tend to bias their judgments of the strengths and weaknesses of various alternatives to make them fit their already-made decision, their implicit favorite. B. HINDSIGHT BIAS 1. Hindsight bias is the tendency for people to perceive outcomes as more inevitable after they have occurred than they did before they occurred. 2. This bias occurs because people feel good about being able to judge things accurately. They are more willing to say they expected positive events, but not negative events. C. PERSON SENSITIVITY BIAS 1. Person sensitivity bias is the tendency to give others too little credit when things are going poorly and too much credit when things are going well. 160 Notes Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten 2. Awareness of this bias is important to the extent that effective decisions rely on accurate information, and this bias may predispose us to perceive others in less than objective ways. D. ESCALATION OF COMMITMENT BIAS Figure 10.9 1. Ineffective decisions sometimes are followed up with still more ineffective decisions. 2. People sometimes “throw good money after bad” because they have “too much invested to quit.” The escalation of commitment phenomenon, the tendency for people to continue to support previously unsuccessful courses of action because they have sunk costs invested in them. 3. Failure to back your own previous courses of action in an organization sometimes can be viewed as an admission of failure, a politically difficult act in an organizations. 4. People may be concerned about saving face, looking good in the eyes of others and oneself. 5. This tendency is primarily responsible for people’s inclination to protect their beliefs about themselves as being rational, competent decision-makers by convincing themselves and others they made the right decision all along, and are willing to back it up. 6. People refrain from escalation of commitment under several conditions: a. People stop making failing investments when available funds for making further investments are limited and the threat of failure is overwhelming. b. People also refrain from escalating commitment when they can diffuse their responsibility for the earlier failing action. The more people feel they are just one of several responsible for a failing course of action, the less likely they are to commit to further failing actions. c. Notes In addition, escalation of commitment is low in organizations where the people who made the ineffective decisions have left and been replaced by others who are not linked to those decisions. d. Finally, people are unwilling to escalate commitment to a course of action when, the total amount invested exceeds the expected gain. 7. Escalation of commitment phenomenon represents a type of irrational decision making. Whether it occurs, however, depends on the various circumstances the decision-makers confront. 161 Figure 10.10 p.381 p.382 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten VI. GROUP DECISIONS: DO TOO MANY COOKS SPOIL THE BROTH? Notes A. WHEN ARE GROUPS SUPERIOR TO INDIVIDUALS? Figure 10.11 1. Whether groups do better or worse than individuals depends on the nature of the task--it depends on how complex or how simple the task is. 2. Complex decision tasks: a. An important decision must be made about a complex problem. The highly complex nature of this situation may overwhelm even an expert, thereby setting the stage for a group to do a better job. Naturally, groups may excel in such situations. b. This does not happen automatically, however. For groups to outperform individuals, several conditions must exist. c. Successful groups tend to be composed of heterogeneous group members with complementary skills. The diversity of opinions offered by members is one major advantage of using groups to make decisions. d. Members must be able to communicate their ideas in an open, nonhostile manner. Conditions under which one individual (or group) intimidates another from contributing can easily negate any potential gain associated with groups of heterogeneous experts. e. Thus, for groups to be superior to individuals, they must be a heterogeneous collection of experts with complementary skills who can contribute to their group’s product freely and openly. 3. Simple decision tasks: a. A situation in which a decision is required on a simple problem with a readily verifiable answer. b. An expert working alone may do even better than a group, because the expert performing a simple task may not be distracted by others or need to convince them of the correctness of his or her solution. c. Whether groups perform better than individuals depends on the nature of the task and the expertise of the members. B. WHEN ARE INDIVIDUALS SUPERIOR TO GROUPS? 1. Most of the problems faced by organizations require a great deal of creative thinking. a. You would expect the complexity of such creative problems would give groups a natural advantage, but this is not the case. b. In fact, on poorly structured, creative tasks, individuals perform better than groups. 162 p.384 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten 2. One approach to solving creative problems commonly used by groups is brainstorming. a. Members are encouraged to present their ideas in an uncritical way and to discuss freely and openly all ideas on the floor. b. Four main rules: o Avoid criticizing others’ ideas. o Share even far-out suggestions. o Offer as many comments as possible. o Build on others’ ideas to create your own. Notes Table 10.3 p.386 3. Does brainstorming improve the quality of creative decisions? a. The results of one research study, individuals were significantly more productive than groups. b. Groups perform worse than individuals on creative tasks. c. Some individuals feel inhibited by the presence of others. d. Groups may inhibit creativity by slowing down the process of bringing ideas to fruition. VII. TECHNIQUES FOR IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DECISIONS A. TECHNIQUES FOR IMPROVING INDIVIDUAL DECISIONMAKING 1. Several steps can be taken to improve the quality of decisions made by individuals. These include training people in ways of improving group performance and guiding people toward ethical behavior. 2. If at least one member can devise a solution, groups may benefit from that individual’s expertise. Thus it follows that the more qualified individual group members are to solve problems, the better their groups as a whole perform. 3. People tend to make four types of mistakes when attempting creative decisions: a. Hypervigilance--frantically searching for quick solutions to problems, or going from one idea to another, of desperate that one idea is not working and another must be considered before time runs out. This problem may be avoided, however, by remembering it is best to stick with one suggestion and then work it out thoroughly. A little reassurance goes a long way towards keeping individuals on the right track and away hypervigilance. b. Unconflicted adherence--sticking to the first idea that comes into their heads without evaluating the consequences. As a result, such people are unlikely to be aware of any problems with their ideas or to consider other possibilities. 163 Web Surfing Exercise: Decision Skills Training p. 400 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten To avoid this, decision-makers are urged to think about the difficulties associated with their ideas, to consider different ideas, etc. c. Notes Unconflicted change--being quick to change their minds and adopt the first new idea to come along. To avoid this decision-makers are encouraged to ask themselves about the risks and problems of adopting that solution, etc. d. Defensive avoidance--decision-makers fail to solve problems effectively because they go out of their way to avoid working on the task at hand. Three things to minimize this problem. First, avoid procrastination. Second, avoid disowning responsibility. Finally, do not ignore potentially corrective information. 4. The ethicality of decisions is an important consideration. The pursuit of quality in organizations demands the highest moral standards. The problem is that even those with high moral values sometimes are tempted to behave unethically. 5. To avoid such temptations--and, thereby, to improve ethical decision making--it may be useful to run your contemplated decisions through an ethics test: a. Does it violate the obvious ‘shall-nots’? b. Will anyone get hurt? c. How would you feel if the newspaper reported your decision on the front page? d. What if you did it 100 times? e. How would you feel if someone did it to you? f. What is your gut feeling? OB In A Diverse World: Are U.S. Businesses Overly Concerned About Ethical Decision? p.388 6. Admittedly, considering these questions will not transform a devil into an angel. Still, they may be useful for judging how ethical the decisions you may be contemplating really are. 7. National culture also may influence people’s perceptions of the ethical appropriateness of a decision. People from different nations may have different views about ethical and unethical business decisions. B. TECHNIQUES FOR ENHANCING GROUP DECISIONS 1. Organizational decision-makers sometimes consult experts to help them make the best decisions. 2. Developed by the Rand corporation, the Delphi technique is a systematic way of collecting and organizing the opinions of several experts into a single decision. Figure 10.12 164 p.390 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes 3. The Delphi process begins by enlisting the co-operation of experts and presenting the problem to them, usually in a letter. a. Each expert then proposes what he/she believes is the most appropriate solution. b. The group leader compiles these individual responses, reproduces them, and shares them with all the other experts in a second mailing. c. At this point, each expert comments on the other experts’ ideas and proposes another solution. d. These individual solutions are returned to the leader, who then compiles them again and looks for a consensus of opinions. If a consensus is reached, the decision is made. e. If not, the process of sharing is repeated until a consensus eventually is obtained. 4. The Delphi technique that it allows the collection of expert judgments without the problems of scheduling a face-toface meeting. 5. Limitations. a. The Delphi process can be very time-consuming. b. The minimum time required for the Delphi technique is estimated to be more than 44 days. 6. When only a few hours are available to make a decision, group discussion sessions can be held in which members interact with each other in an orderly, focused fashion. 7. The Nominal group technique (NGT) brings together a small number of individuals (usually 7 to 10) who systematically offer their individual solutions to a problem and share their personal reactions to those solutions. . 8. The NGT has several advantages and disadvantages. a. It can lead to a group decision in only a few hours. b. It also discourages any pressure to conform. c. It requires a trained group leader. d. It requires only one narrowly defined problem be considered at a time. 9. Traditionally, nominal groups meet face-to-face. Technology enables such groups to meet even when the members are far away from each other. a. Electronic meeting systems allow individuals in different locations to participate in group conferences via telephone lines or direct satellite transmissions. b. Automated decision conferences are just nominal groups meeting in a manner that approximates face-toface contact. 10. Both nominal and Delphi groups are more productive than face-to-face interacting groups. 165 Figure 10.13 p.391 Group Exercise: Running A Nominal Group: Try It Yourself p. 399 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes 11. Groups are likely to accept their decisions and be committed to them if the members have been actively involved in making them. Thus, the more detached and impersonal atmosphere of nominal and Delphi groups sometimes makes their members less likely to accept decisions. 12. Another way of structuring group interaction is known as The Stepladder technique. This approach minimizes the tendency for group members to be unwilling to present their ideas. Figure 10.15 p.392 13. This is accomplished by adding new members one at a time and requiring each to present his/her ideas independently to a group that already has discussed the problem at hand. a. Two people work on a problem independently. Then, they come together to present their ideas and to discuss solutions jointly. b. While the two-person group is working, a third person also considers the problem. c. This individual then presents his or her ideas to the twoperson group and joins in a three-person discussion of a possible solution. d. Then a fourth person works on the problem, presents, etc. 14. Each individual must be given enough time to work on the problem, to present, and to discuss in order to reach a preliminary decision before the next person is added. The final decision is made only after all individuals have been added to the group. 15. The rationale is that by forcing each person to present independent ideas the new person will not be influenced by the group and the group is required to consider a constant infusion of new ideas. 16. Members of stepladder groups report feeling more positive about their group experiences than their counterparts in conventional groups. VIII. COMPUTER-BASED APPROACHES TO PROMOTING EFFECTIVE DECISIONS A. ELECTRONIC MEETINGS 1. Electronic meeting bring people together from different locations for a meeting via telephone or satellite transmissions either on television monitors or computer screen. 2. They allow groups to assemble more conveniently than face-to-face meetings and are generally just as effective. 166 Practicing OB: The Disruptive Manager p. 401 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Notes B. COMPUTER-ASSISTED COMMUNICATION 1. Computer assisted communication refers to sharing information, such as text messages and data relevant to the decision over computer networks. Figure 10.17 p.394 2. It can be a useful tool to share information, however, better do not necessarily follow. 3. Researchers found in one study that “openness to experience” was an important variable for more effective decisions. Because the technology was so new, those who scored high performed better than those who scored low on this variable. 4. Training may be able to compensate for this lack of “openness” making the technology more useful in decision making. C. GROUP DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS 1. A GDSS is an interactive computer based system that combines communication, computer, and decision technologies to improve the effectiveness of group problem solving meetings. 2. Sometimes groups make poor decisions because members do not share information. A GDSS may avoid this problem because ideas are recorded anonymous making people less reluctant to share ideas. 3. Researchers found that not only did people share more information using a GDSS, but better decisions resulted. 167 Best Practices: Naval Officers Use GDSS p.362 Web Surfing Exercise: Decision Support Systems p. 400 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Summary and Review of Learning Objectives 1. Identify the steps in the analytical model of decision making and distinguish between the various types of decisions that people make. According to the analytical model of decision making, the making of decisions is a multistep process through which (1) a problem is identified, (2) solution objectives are defined, (3) a predecision is made (i.e., a decision about how to make a decision), (4) alternatives are generated, (5) these alternatives are evaluated, (6) an alternative is chosen, (7) that alternative is implemented, and then (8) a followup evaluation occurs to determine if the problem still exists. Decisions made in organizations can be characterized as being either programmed, routine decisions made according to preexisting guidelines or nonprogrammed decisions requiring novel and creative solutions. Decisions also differ with respect to the amount of risk involved, ranging from those in which the decision outcomes are relatively certain to those in which the outcomes are highly uncertain. Uncertain situations are expressed as statements of probability based on either objective or subjective information. Decisions also differ with respect to whether they are made by high-level organizational officials (top-down decisions) or by employees themselves (empowered decisions). 2. Describe different individual decision styles and the various organizational and cultural factors that influence the decision-making process. There are individual differences in the way people make decisions. Generally, people demonstrate one of four dominant decision styles: directive (preference for simple, clear solutions), analytical (willingness to consider complex situations based on ambiguous information), conceptual (a humanistic and artistic orientation), or behavioral (a concern for the organization). Within organizations, decision quality may be adversely affected by severe time constraints and by political face-saving pressures. Decisions made in organizations also are affected by the national culture in which the organization exists. For example, Americans are more likely to confront problems as decisions that need to be made, whereas people from Thailand are more likely to accept these problems as they are. Also, whereas Americans make decisions in a highly individualistic way (by looking out for themselves), Asians are more likely to make decisions in a collective manner (by taking into account the group or organization). 3. Distinguish among three approaches to how decisions are made: the rational economic model, the administrative model, and image theory. The rational-economic model characterizes decision makers as thoroughly searching through perfect information to make an optimal decision. This is a normative approach, in that it describes how decision makers ideally ought to behave to make the best possible decisions. In contrast, the administrative model is a descriptive approach, which describes how decision makers actually behave. It recognizes that limitations imposed by people’s ability to process the information needed to make complex decisions (bounded rationality and bounded discretion) restrict decision makers to making satisficing decisions—solutions that are not optimal but are good enough. An alternative approach, image theory, recognizes that decisions are made in an automatic, intuitive fashion. It claims that people will adopt a course of action that best fits their individual principles, current goals, and plans for the future. 4. Identify the various factors that lead people to make imperfect decisions. People make imperfect decisions due to cognitive biases. One such bias, framing, refers to the tendency for people to make different decisions based on how a problem is presented. For example, when a problem is presented in a way that emphasizes positive gains to be received, people tend to make conservative, risk-averse decisions, whereas when the same problem is presented in a way that emphasizes potential losses to be suffered, people tend to make riskier decisions. Simple rules of thumb, known as heuristics, also may bias decisions. For example, according to the availability heuristic, people base their judgments on information readily available to them, and according to the representativeness heuristic, people are perceived in stereotypical ways if they appear to be representatives of the categories to which they belong. People also are biased toward implicit favorites, alternatives they prefer in advance of considering all the options. Other alternatives, confirmation candidates, are considered for purposes of convincing oneself that one’s implicit favorite is the best alternative. Decisions also are biased because of the tendency to believe that we were far better at judging past events than we actually were (known as the hindsight bias) and the tendency for people to give too little credit to others when things are going poorly and too much credit when things are going well (known as the person sensitivity bias). Finally, decisions are biased insofar as people tend to escalate commitment to unsuccessful courses of action because they have 168 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten sunk costs invested in them. This occurs in large part because people need to justify their previous actions and wish to avoid having to admit that their initial decision was a mistake. 5. Compare the conditions under which groups make more superior decisions than individuals and when individuals make more superior decisions than groups. Groups make more superior decisions than individuals when these are composed of a heterogeneous mix of experts who possess complementary skills. However, groups may not be any better than the best member of the group when performing a task that has a simple, verifiable answer. Individuals make more superior decisions than face-to-face brainstorming groups on creative problems. However, when brainstorming is done electronically—that is, by using computer terminals to send messages—the quality of decisions tends to improve. 6. Describe various traditional techniques and high-tech techniques that can be used to enhance the quality of individual decisions and group decisions. Decision quality may be enhanced in several different ways. First, the quality of individual decisions has been shown to improve following individual training in problem solving skills. Training in ethics also can help people make more ethical decisions. Group decisions may be improved in three ways. First, in the Delphi technique, the judgments of experts are systematically gathered and used to form a single joint decision. Second, in the nominal group technique, group meetings are structured so as to elicit and evaluate systematically the opinions of all members. Third, in the stepladder technique, new individuals are added to decision-making groups one at a time, requiring the presentation and discussion of new ideas. Contemporary techniques also employ the use of computers as aids in decision making. One of these is known as electronic meetings. These are computer networks that bring individuals from different locations together for a meeting via telephone or satellite transmissions, either on television monitors or via shared space on a computer screen. Another computer-based approach is computer-assisted communication—the sharing of information, such as text messages and data relevant to the decision, over computer networks. Finally, computers have been used to facilitate decision making by way of group decision support systems. These are interactive computer-based systems that combine communication, computer, and decision technologies to improve the effectiveness of group problem solving meetings. Questions for Review 1. What are the general steps in the decision-making process, and how can different types of organizational decisions be characterized? Answer: According to the analytical model of decision making, the making of decisions is a multistep process through which (1) a problem is identified, (2) solution objectives are defined, (3) a predecision is made (i.e., a decision about how to make a decision), (4) alternatives are generated, (5) these alternatives are evaluated, (6) an alternative is chosen, (7) that alternative is implemented, and then (8) a follow-up evaluation occurs to determine if the problem still exists. Decisions made in organizations can be characterized as being either programmed, routine decisions made according to preexisting guidelines or nonprogrammed decisions requiring novel and creative solutions. Decisions also differ with respect to the amount of risk involved, ranging from those in which the decision outcomes are relatively certain to those in which the outcomes are highly uncertain. Uncertain situations are expressed as statements of probability based on either objective or subjective information. Decisions also differ with respect to whether they are made by high-level organizational officials (top-down decisions) or by employees themselves (empowered decisions). 2. How do individual decision style, group influences, and organizational influences affect decision making in organizations? Answer:There are individual differences in the way people make decisions. Generally, people demonstrate one of four dominant decision styles: directive (preference for simple, clear solutions), analytical (willingness to consider complex situations based on ambiguous information), conceptual (a humanistic and artistic orientation), or behavioral (a concern for the organization). Within organizations, decision quality may be adversely affected by severe time constraints and by political face-saving pressures. 3. What are the major differences between the rational-economic model, the administrative model, and the image theory approach to individual decision making? Answer: The rational-economic model characterizes decision makers as thoroughly searching through perfect information to make an optimal decision. This is a normative approach, in that it 169 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten describes how decision makers ideally ought to behave to make the best possible decisions. In contrast, the administrative model is a descriptive approach, which describes how decision makers actually behave. It recognizes that limitations imposed by people’s ability to process the information needed to make complex decisions (bounded rationality and bounded discretion) restrict decision makers to making satisficing decisions—solutions that are not optimal but are good enough. An alternative approach, image theory, recognizes that decisions are made in an automatic, intuitive fashion. It claims that people will adopt a course of action that best fits their individual principles, current goals, and plans for the future. 4. Explain how each of the following factors contributes to the imperfect nature of decisions: framing effects, reliance on heuristics, decision biases, and the tendency to escalate commitment to a losing course of action. Answer: Framing is the tendency for people to make different decisions based on how the problem is presented to them. Scientists have identified three different forms of framing effects that occur when people make decisions: Risky choice frames, Attribute framing, and Goal framing. Heuristics are simple decision rules used to make quick decisions about complex problems. People’s decisions are biased by their tendency not to consider all the available relevant information. Finally, the escalation of commitment phenomenon is the tendency for people to continue to support previously unsuccessful courses of action because they have sunk costs invested in them. Each of these factors inhibit effective decision making. 5. When it comes to making decisions, under what conditions are individuals superior to groups and under what conditions are groups superior to individuals? Answer: Groups make more superior decisions than individuals when they are composed of a heterogeneous mix of experts who possess complementary skills. However, groups may not be any better than the best member of the group when performing a task that has a simple, verifiable answer. Individuals make more superior decisions than face-to-face brainstorming groups on creative problems. However, when brainstorming is done electronically—that is, by using computer terminals to send messages—the quality of decisions tends to improve. 6. What traditional techniques and computer-based techniques can be used to improve the quality of decisions made by groups or individuals? Answer: Decision quality may be enhanced in several different ways. First, the quality of individual decisions has been shown to improve following individual training in problem solving skills. Training in ethics also can help people make more ethical decisions. Group decisions may be improved in three ways. First, in the Delphi technique, the judgments of experts are systematically gathered and used to form a single joint decision. Second, in the nominal group technique, group meetings are structured so as to elicit and evaluate systematically the opinions of all members. Third, in the stepladder technique, new individuals are added to decision-making groups one at a time, requiring the presentation and discussion of new ideas. Contemporary techniques also employ the use of computers as aids in decision making. One of these is known as electronic meetings. Another computer-based approach is computer-assisted communication—the sharing of information, such as text messages and data relevant to the decision, over computer networks. Finally, computers have been used to facilitate decision making by way of group decision support systems. Experiential Questions 1. Think of any decision you recently made. Would you characterize it as programmed or nonprogrammed? Highly certain or highly uncertain? Top-down or empowered? Explain your answers. Answer - Students’ examples will vary but should cover these basics. Programmed and nonprogrammed. A decision that is made repeatedly and according to a pre-established set of alternatives is a programmed decisions, routine decisions by lower-level personnel that rely on predetermined courses of action. In contrast, nonprogrammed decisions, ones for which no ready-made solutions exist. In these cases, the decision-maker confronts a unique situation, and the solutions are equally novel. 170 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Certain and uncertain decisions. Degrees of certainty and uncertainty are expressed as statements of risk. All organizational decisions involve some degree of risk, which ranges from complete certainty (i.e., no risk) to complete uncertainty or “a stab in the dark” (i.e., high risk). What makes a decision risky is the probability of obtaining the desired outcome. Top-down and empowered decision. Traditionally, making decisions in organizations was a manager’s job. Subordinates collect information and give it to their superiors, who then use it to make decisions. Known as top-down decision making, this approach puts the power to make decisions in the hands of managers. 2. Identify ways in which various decisions you have made were biased by framing, heuristics, the use of implicit favorites, and the escalation of commitment. Answer: Students’ examples will vary but should cover these basics. Framing is the tendency for people to make different decisions based on how the problem is presented to them. Reliance on heuristics. The use of certain rules to make decisions. Bias toward implicit favorites reflects individuals’ tendency to pick an implicit favorite option (i.e., a preferred alternative) early in the decision-making process. Subsequent options are not given serious consideration. They are used merely to convince oneself the implicit favorite is indeed the best choice. Escalation of commitment. People sometimes “throw good money after bad” because they have “too much invested to quit,” the escalation of commitment phenomenon, the tendency for people to continue to support previously unsuccessful courses of action because they have sunk costs invested in them. 3. Think of various decision-making groups in which you may have participated over the years. Do you think that groupthink was involved in these situations? What signs were evident? Answer: Students answers will vary, but they should include a discussion of the characteristics of groupthink: complacency, over confidence, wide spread agreement, lack of conflict, and lack of reflection on the decision. Questions to Analyze 1. Imagine that you are a manager facing the problem of not attracting enough high quality personnel to your organization. Would you attempt to solve this problem alone or by committee? Explain your reasoning. Answer: It depends on how you frame the problem, simple--we don’t pay enough, or complex--our corporate culture, our competition, our business environment are affecting our recruiting. Students’ responses should reflect certain basics depending on how they frame the problem. Whether groups do better or worse than individuals depends on the nature of the task--it depends on how complex or how simple the task is. An important decision must be made about a complex problem. The highly complex nature of this situation may overwhelm even an expert, thereby setting the stage for a group to do a better job. Naturally, groups may excel in such situations. A situation in which a decision is required on a simple problem with a readily verifiable answer. An expert working alone may do even better than a group, because the expert performing a simple task may not be distracted by others or need to convince them of the correctness of his or her solution. For a summary of some key considerations. Also if the problems is seen as a poorly structured, creative task, than an individual would perform better than a group. 2. Suppose you were on a committee charged with making an important decision and that committee was composed of people from various nations. How do you think this might make a difference in the way the group operates? Answer: Yes both in terms of their focus on collectivistic versus individualistic approaches and what they consider as ethical behavior. Even if people followed the same basic steps when making decisions, there would still be widespread differences in the way people from various cultures might go about doing so. 171 Greenberg & Baron: Behavior In Organizations Chapter Ten Thailand, Indonesia, or Malaysia, however, managers often accept nonperformance by suppliers as fate and allow the projects to be delayed. An American, Canadian, or Western European manager, perceived such a situation as a problem in need of a decision, whereas Thai, Indonesian, or Malaysian managers perceive no such problem. Cultures also differ regarding the nature of the decision-making unit they typically employ. In the United States, where people tend to be highly individualist, individual decisions are common. In more collectivist cultures such as Japan, however, it is inconceivable for someone to make a decision without first gaining the acceptance of his/her immediate colleagues. Swedes may totally ignore an organizational hierarchy and contact whomever is needed to make a decision, however high-ranking that individual may be. In India, however, where autocratic decision making is expected, a manager consulting a subordinate about a decision is considered to be a sign of weakness. Yet another cultural difference deals with time. In the United States, one mark of a good decision maker is decisive, willing to make an important decision without delay. In Egypt, the more important the matter, the more time the decision-maker is expected to take. There tend not to be equally similar norms regarding ethical and unethical behavior. Rather, ethical standards vary widely among capitalist nations, and Americans appear to be more concerned than their foreign counterparts about ethics--too much so, according to some. 3. Argue pro or con: “All people make decisions in the same manner.” Answer: There are meaningful differences between people in their orientation toward decisions, in their decision style. Although most managers may have one dominant style, they often use many different styles. Being aware of people’s decision styles is a potentially useful way of understanding social interactions in organizations. People take very different approaches to the decisions they make. Coupled with their interpersonal skills, their personalities lead them to approach decisions in consistently different ways. The decision-style model classifies four major decision style. Critical Thinking Questions 1. As an individual who is potentially overwhelmed by statistics and observations about individual players, how do you think Lemmerman’s own decision processes may be biased? Answer: He is a highly experience recruiter—he may make decisions quickly because of his experience or using a heuristic. 2. In what way do you think that the quality of the decisions made by officials from the New Orleans Saints is helped or harmed by the practice of making draft decision as a group? Answer: Groupthink could be a potential problem. On the plus side, officials are more likely to support decisions that they have had a say in. 3. In what ways do you think that escalation of commitment may be involved in the decisions Lemmerman makes for the teams? Answer: It is possible that the time he has spent recruiting a potential team member may bias him to favor that individual over others. However, his use of a database does help to make the process more objective because the availability of statistics on each player. 172