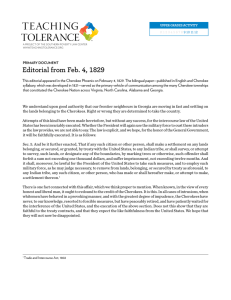

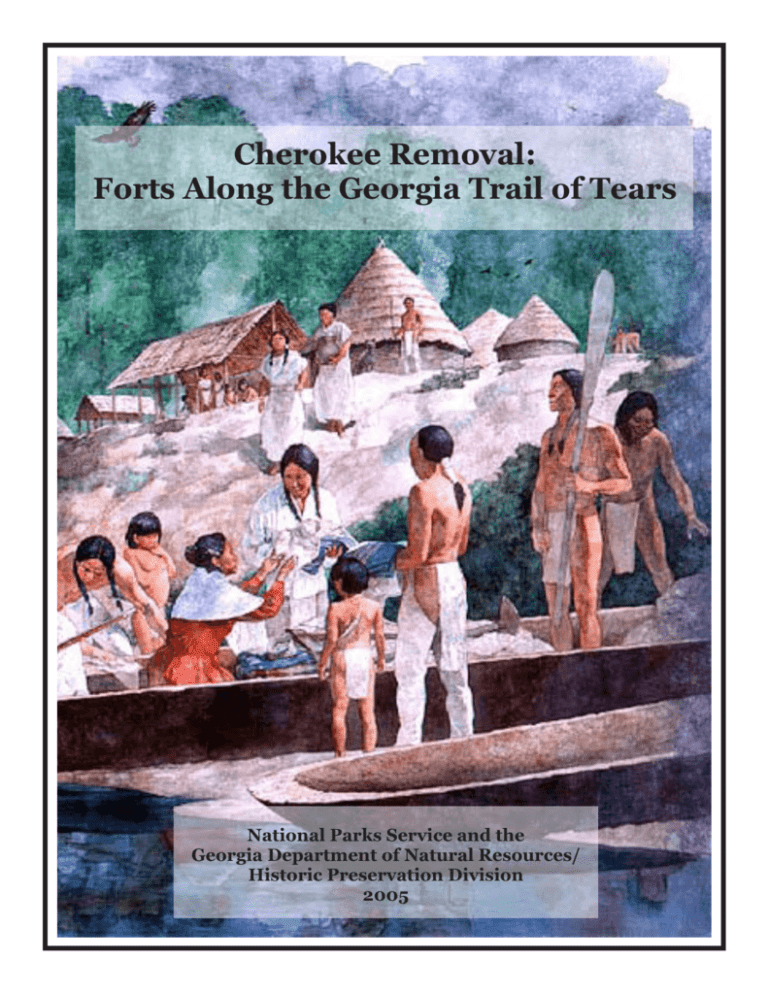

Cherokee Removal: Forts Along the Georgia Trail of Tears

advertisement