Copyright by Paula Sanmartín 2005

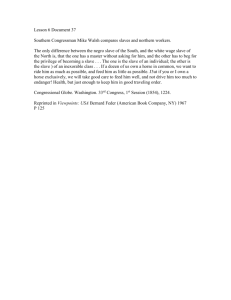

advertisement