SUPPLEMENTAL PAGE FOR CONTEMPT PAPER DUE PROCESS

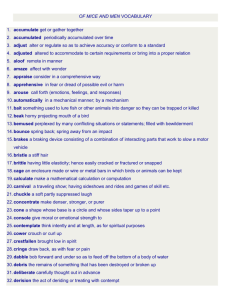

advertisement

SUPPLEMENTAL PAGE FOR CONTEMPT PAPER DUE PROCESS AND THE COLLECTION OF CHILD SUPPORT THROUGH THE POWER OF CONTEMPT This topic arises out of the United States Supreme Court’s decision of Turner v. Rogers, ET Al. 564 U.S.____(2011), No. 10-10, June 20, 2011 (subject to revision before publication). The Turner case (a five to four decision) affirmed the proposition of the appointment of counsel not being required under the Sixth Amendment in civil contempt but under the Due Process Clause added a caveat that the State must have in place alternative procedures that assure a fundamentally fair determination of the critical incarceration related question which is, whether the supporting parent is able to comply with the support order. The Turner Case majority stated it must “ decide whether the Due Process Clause grants an indigent defendant, such as Turner, a right to state-appointed counsel at a civil contempt proceeding, which may lead to his incarceration.” The Turner Court considered an indigent's right to paid counsel when a contempt proceeding is used to ensure the custodial parent receives support payments or the government receives reimbursement but made no ruling relevant to a government case. (The Court seems to be inferring the right to counsel may exist when the government is pursuing the contempt and is represented by an attorney.) This case held: that the Due Process Clause does not automatically require the provision of counsel at civil contempt proceedings to an indigent individual who is subject to a child support order, even if that individual faces incarceration (for up to a year). In particular, that Clause does not require the provision of counsel where the opposing parent or other custodian (to whom support funds are owed) is not represented by counsel and the State provides alternative procedural safeguards equivalent to: adequate notice of the importance of ability to pay, fair opportunity to present, and to dispute, relevant information, and court findings. The Court has made clear (in a case not involving the right to counsel) that, where civil contempt is at issue, the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause allows a State to provide fewer procedural protections than in a criminal case. Hicks v. Feiock, 485 U.S. 624, 637-641(1988) (State may place the burden of proving inability to pay on the defendant). The Turner Court (citing Lassiter v. Department of Social Servs. Of Durham Cty. ,452 U. S. 18 (1981)) recognized the preeminent generalization which is an indigent’s right to appointed counsel in civil cases “exist[s] only where the litigant may lose his physical liberty if he loses the litigation” and added that right does not exist “in all such cases.” The Turner Court considered an indigent's right to paid counsel at such a contempt proceeding (using contempt to ensure the custodial parent receives support payments or the government receives reimbursement). It appears the child support collection process must include an explicit notice to the alleged contemnor that his ability to have paid or to pay will be the crucial issue. The ability to comply has always been a key issue. The burden of showing the inability to have complied does not appear to have been altered. Clear notice of the importance of that issue is now required! A means of gathering relevant financial information (perhaps a form) also seems to be required (of course the usual due process rights such as notice and the right to be heard apply. (See footnote 46.) The Court must in its’ orders clearly address the issue of ability or inability of the contemnor to have complied. This case does not directly alter what has been stated in this material but it expands upon the due process issue of representation and in so doing limits the assertion that a defendant in a civil contempt case does not have a right to an attorney. However, certain excerpts from the case give rise to unanswered questions. The Turner Court expressly stated it did not address cases where the State is collecting reimbursement of support owed to the State or unusually complex cases. Given the emphasis placed on the symmetry of representation (both or neither being represented) and the reference to complexity being such that one can fairly be represented only by a trained advocate, one is inclined to conclude counsel for indigents’ in such cases is going to be required. Therefore in such cases a violation of due process may exist and might result in a reversal if appealed. This conclusion is reinforced by the following language: the Due Process Clause does not require the provision of counsel where the opposing parent or other custodian (to whom support funds are owed) is not represented by counsel. As an aside, in defense of our Supreme Court the dissenting opinion in the Turner Court makes it clear the only issue presented our Court was the application of the Sixth Amendment. As such the minority would affirm. The language and reasoning of the minority opinion is a great example of logic and the application of accepted appellate principles. The logic of not allowing a general provision (here meaning the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment) to render a specific one (here the Sixth Amendment) superfluous seems compelling. It would solve the appealed issue without unnecessarily creating new and unanswered issues. THE PAPER WAS PRINTED JUST BEFORE THE TURNER CASE. THE SOUTH CAROLINA SUPREME COURT ISSUED AN ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER AND FORMS SUBSEQUENT TO THAT CASE. IT ALSO RENDERED AN OPINION ON CONTEMPT SUBSEQUENT TO THE PRINTING. THE COMPUTER DISC REFERENCES THOSE NEW CASES.