BY MATTHEW BRAGA why he aspires to be the “rococo, Jewish, city

advertisement

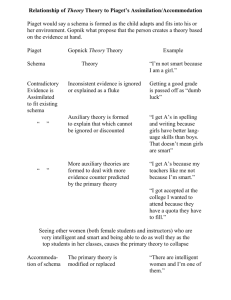

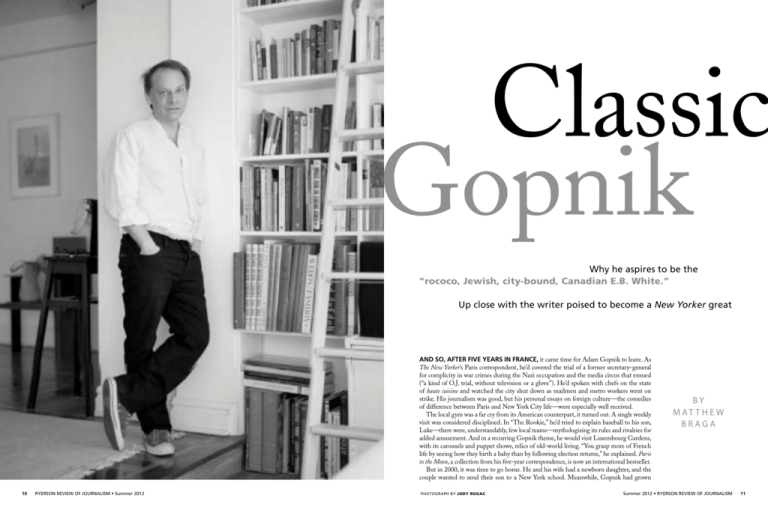

Classic Gopnik Why he aspires to be the “rococo, Jewish, city-bound, Canadian E.B. White.” Up close with the writer poised to become a New Yorker great And so, after five years in France, it came time for Adam Gopnik to leave. As The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, he’d covered the trial of a former secretary-general for complicity in war crimes during the Nazi occupation and the media circus that ensued (“a kind of O.J. trial, without television or a glove”). He’d spoken with chefs on the state of haute cuisine and watched the city shut down as mailmen and metro workers went on strike. His journalism was good, but his personal essays on foreign culture—the comedies of difference between Paris and New York City life—were especially well received. The local gym was a far cry from its American counterpart, it turned out. A single weekly visit was considered disciplined. In “The Rookie,” he’d tried to explain baseball to his son, Luke—there were, understandably, few local teams—mythologizing its rules and rivalries for added amusement. And in a recurring Gopnik theme, he would visit Luxembourg Gardens, with its carousels and puppet shows, relics of old-world living. “You grasp more of French life by seeing how they birth a baby than by following election returns,” he explained. Paris to the Moon, a collection from his five-year correspondence, is now an international bestseller. But in 2000, it was time to go home. He and his wife had a newborn daughter, and the couple wanted to send their son to a New York school. Meanwhile, Gopnik had grown 10 Ryerson review of journalism • Summer 2012 photoGRAPH BY Jody rogac BY M AT T H E W BRAGA Summer 2012 • Ryerson review of journalism 11 “You learn something about what Adam thinks, and you learn extraordinary things about the world,” says Malcolm Gladwell. “But he remains somewhat opaque” wary of repeating himself. “Your readers know it even if they can’t put their finger on what it is,” he says. “The moment I thought self-consciously about how I would engineer a little comedy of difference”—learning how to drive, for example—“that’s shtick.” When the 55-year-old author and essayist writes about himself, he’s not really the subject. We don’t read Adam Gopnik to hear about him, but to hear from him—what he thinks and how the world looks through his eyes. His comic sentimental essays are not merely inward-looking observations; he avoids self-indulgence in pursuit of a greater truth. He excels at this style of writing—and yet, he is ready to move on. His children are getting older, their experiences no longer his to share. And so he writes about them less. Where he once documented the death of his daughter’s fish or his young son’s linguistic errors, he now draws connections between Darwin and Lincoln instead. And just as he left Paris, in part, fearful of shtick, he’d rather not be typecast as the man who primarily writes about his kids. In the prime of his career, he no longer hesitates to call himself an essayist, and has set his sights on a higher standard defined by The New Yorker’s early literary greats—a difficult goal for any writer to achieve. His focus has shifted to grander, more humanist subjects, from information overload to the history of romanticized winter. But in becoming an old-school essayist, there is certainly an element of 12 Ryerson review of journalism • Summer 2012 risk. On the one hand, readers are enthusiastic about long-form writing again in a way that no one could have predicted. Online sites such as Longreads exist for the sole purpose of finding the best in-depth stories on the web. On the other, a declining print industry means smaller budgets and fewer features, things once in abundance for essayists of old. And perhaps most importantly, there is no guarantee that new readers will take to Gopnik’s style, or that it will succeed in any enduring way. But if a classical revival is what Gopnik wants, there might not be a better time than now. Though Montreal remains his hometown, he is not, technically, Canadian. Born in Philadelphia in 1956, he was 11 when his family moved to Quebec. One of six children— the only one not to have pursued a PhD—he lived in Moshe Safdie’s ambitious Habitat 67 apartment complex. He earned a bachelor’s degree in art history from McGill in 1980, and met his future wife, filmmaker Martha Parker. Later that year, the couple hopped a bus to New York City. Following stints editing at GQ and the publishing house Knopf, he joined The New Yorker in 1986, after sending the magazine unsolicited pieces—unsuccessfully—for years. His debut, “Quattrocento Baseball,” combined two disparate topics—baseball and art history—in what would become typical Gopnik fashion. He spent the following years writing Talk of the Town pieces, before the section had bylines. But CBC Ideas producer Paul Kennedy says Gopnik’s tales were easy to identify. There were pieces about the writer’s SoHo loft, the building full of “crazy artists, not making a lot of money, but with lots of hopes and dreams,” says his friend. “They captured the poignant essence of being an artist in New York.” In one piece, simply titled “Hay,” from 1989, Gopnik helped a conceptual artist rescue bales from a leaking apartment. “Water was coming through the ceiling,” he wrote, “like blood in an old Vincent Price movie—slipping spookily down the wall in sheets.” In a later story, his apartment fell victim to a leak of its own, a strange sugary substance with the colour and consistency of blood, another art project gone awry. In Paris, he was happy to be rid of that old loft. When the family returned to New York in 2000, Gopnik found a different Manhattan than the one he left—safer, cleaner, but far from innocent. There was 9/11, the smell of burned buildings and buried bodies like “smoked mozzarella.” And in a piece titled “Last of the Metrozoids,” he discussed the loss of his close friend and graduate school mentor Kirk Varnedoe to cancer. While Paris to the Moon detailed the changing metropolis of turn-of-the-century France, Through the Children’s Gate was a coming-of-age story of a country in mourning and a city in repair. Gopnik still watches his beloved Montreal Canadiens play from his home in New York. Such is Gopnik’s man-about-town persona, offering up slices of New York City life—though not necessarily his own. Malcolm Gladwell jokingly referred to such essays as personal pieces that don’t reveal anything personal. “You learn something about what Adam thinks, and you tend to learn extraordinary things about the world,” says his New Yorker colleague. “But he remains somewhat opaque. And I think that’s actually quite lovely.” There is a characteristic start to every Gopnik story, says The New Yorker’s editorial director, Henry Finder. With most writers, assigning ideas means suggesting a few topics and seeing what sticks. “But the experience is very different with Adam,” says his editor. “You can sort of choose any topic at random.” After Gopnik bought a small Havanese poodle last summer, Finder suggested a story about dogs. Gopnik, however, was hesitant. He wasn’t sure he would have anything to say. But with a bit of prodding, Gopnik, in a breathless account of dates, details, and facts, often finds he has more to say about the topic at hand than he initially thought. “He will, almost in the process of letting you down, start writing the piece,” says Finder. What once seemed like a non-story becomes a finished, 4,000-word piece the following week. But Gopnik says he wouldn’t be able to get anything done were it not for the pile of reading his editor suggests before the start of each piece. While Finder is no doubt instrumental, Gopnik has a knack for drawing unlikely connections between concepts and people that might not seem obvious to anyone else. Take, for example, Charlie Ravioli, the imaginary friend of his then eight-year-old daughter, Olivia. “Bumping into Mr. Ravioli” is one of Gopnik’s most popular pieces. What is, on the surface, an absurd story of childhood imagination—many children have a made-up friend, but Olivia’s might be the only one too busy to play with her—is actually a smartly worded commentary on the hustle and bustle of New York City life. It’s a technique Gopnik uses often. The death of his daughter’s goldfish is actually about the larger theme of mortality. A trip to the farmer’s market with a handful of chefs reveals that cooking is not all that dissimilar from writing. The final product, be it soup or story, unites people around a table in consumption and conversation. “The key to writing—at least, the kind of writing that I do, the kind of personal essays I write,” Adam explains, “is that the ‘I’ has to become ‘you.’” In the series of apartment pieces that Kennedy found so endearing, the reader isn’t expected to actually identify with the antics of Gopnik’s photoGRAPH BY Luke Gopnik-Parker SoHo neighbours, but with the concept of crazy neighbours—the idea that everyone has at least one. It’s about making the experience relatable. Even if, on the surface, the topic isn’t something that seems immediately familiar—say, a community of feral parrots in “Power and the Parrot”— Gopnik eventually makes the connection. The parrots, which come from outside North America, recall the country’s ethnic origins—their nests “only slightly smaller than the spaces that are usually rented in the city… for nine hundred dollars a month.” Forced to adapt, the non-indigenous birds are a proxy for new immigrants to old New York. And for second- and even third-generation Americans, it’s a concept with which many can relate. The comic sentimental essay, says Gopnik, is “a kind of antimemoir, a nonconfession confession, whose point is not to strip experience bare, but to use experience for some other purpose: to draw a moral or construct an argument, make a case or just tell a joke.” Though all personal writing starts from the inside, with an inner passion or obsession, it’s not a colonoscopy. Of the writers he admires, this approach to writing is not uncommon. Gopnik points to the English author Virginia Woolf, for example, who wrote essays on everything from feminism to food in the early 20th century, or golden-era New Yorker journalist A.J. Liebling’s stories on the intricacies of war and Summer 2012 • Ryerson review of journalism 13 boxing. “You can’t be an essayist on a single subject,” explains Gopnik. “Then you’re not an essayist, you’re an expert.” A New York Times obituary following Liebling’s death in 1963 said that as his style matured, “it became convoluted, subtle and abounding in unlikely allusions.” Recounting a fight, for example, “might be a delicate embroidery on a theme suggested by a medieval Arabian historian.” He was an amateur boxer in his younger years, and even spent a year in Paris. As with E.B. White, who wrote about pigs on his farm and the accents of Maine residents, to riff imaginatively on a variety of topics requires the mundanity of everyday life. Be it tales of weekly psychoanalysis sessions or his son’s football team, Gopnik mediates on the broomstick, not the witch’s broom. White, for example, realized during his early days at The New Yorker “that writing of the small things of the day, the trivial matters of the heart . . . was the only kind of creative work which I could accomplish with any sincerity or grace.” Gopnik, to an extent, is of a similar breed. Both have taste buds and their little geniuses reflect flatteringly on their own achievements.” It wasn’t exactly glowing. Nor was a 1996 Salon article that decried the “tortured sentences and haphazard arguments” used to convey the mundane details of Gopnik’s Parisian life. “With critics,” says Gopnik, “the things that they don’t like are always the things that you’re best at.” Writing, to him, is a business of perfection, and every sentence should shine with its own unique charm. “But if you’re seen to digress, readers hate that,” he admits. “They feel it’s selfindulgent, that you’re imposing on their time.” In her 1999 book Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker, Renata Adler, a former writer at the magazine, characterized the distinctive structure of a Gopnik piece. Each would begin by presenting a commonly held belief, she said, and then work to disprove it. “Here is what I have discovered is, in fact, the case,” mimicked Adler, “and present to you here, at this very moment, for the first time, ever.” There were “The moment I thought selfconsciously about how I would engineer a little comedy of difference”—for example, learning how to drive—“that’s shtick,” says Gopnik GOPNIK ON… John Stuart Mill “You think of him as the absolute Englishman, but he was a wild francophile who was buried in France because he preferred the country to England.” Garrison Keillor “The greatest storyteller of our time. There’s not a single Lake Wobegon story that I don’t take pleasure in reading in bed at night.” Calvin Trillin “He is an immensely affable, funny, folksy family guy. But he has been through all the normal traumas of human existence, and they leave less trace on his voice than they do on his self.” John Milton “Reading Paradise Lost, I was so excited by it I went to Mister Steer, a hamburger place in Montreal, and I just sat, ate a burger, and read.” E.B. White “I have a certain—probably deplorable—editorializing, moralizing vein, and I see that in White as well.” Randall Jarrell written children’s books—White is the author of Charlotte’s Web—and published collected essays outside the magazine. But times have changed. Perhaps a more pressing question for the wider journalism community is how many publications are still willing—and financially capable—to support the kind of writing Gopnik wants to do. Many magazines, he suspects, now essentially live online, with “a sort of memorial issue that no one sees.” But still he remains loyal to print, a disciple of Liebling, Woolf, and White. “And however inadequate I am,” he says, “that’s certainly the measuring rod I’d like to see used.” Bullshit. That’s what New Yorker editor David Remnick thinks of Gopnik’s critics. One piece in particular seems to set him on edge. In 2007, Vanity Fair’s James Wolcott pointedly asked if Gopnik was “put on this earth to annoy” before launching into a scathing critique of Through the Children’s Gate. “This bountiful note of yuppie triumphalism warbles through the book,” he wrote of the family, as “their exalted 14 Ryerson review of journalism • Summer 2012 numerous problems with this approach, she argued—foremost, that it treated readers as idiots, and painted Gopnik as the progenitor of new and amazing thoughts. But as far as Remnick is concerned, “The day any of these people write anything even remotely as fine and intelligent as Adam Gopnik will be a cold day in hell.” The New Yorker has long reveled in the sort of highbrow intellectualism that some revere and others resent. Gopnik is a frequent target of both sentiments. But such critiques miss the point. They misunderstand the Gopnik essence, says Finder—not selfdisplay for its own sake, but in service of a greater narrative. Gopnik does admit that there are times when “the ‘I’ stubbornly refuses to become a ‘you,’” and those are the stories that often fail to resonate. He’s become a regular at the Moth, a New York-based collective of storytellers that holds regular spoken-word events. The stories are often personal, though far from confessional. Gopnik adapted “Bumping into Mr. Ravioli,” for example, and performed his popular “LOL” story—about a miscommunication with his son over “One of the writers I most admire. He had a terribly difficult inner life and ended up committing suicide. But his voice is one of just matchless ebullience and life-affirming wit and charm.” Woody Allen “The awkwardness is part of the authenticity. But it’s not that way in writing. Awkward on the page is just awkward.” Karl Popper “I thought he was the greatest philosopher in the world. But to my shock, he was the most irascibly paranoid human being who had ever lived, like a wounded panther in his resentments.” the meaning of the internet initialism—for the first time. Both were well received because they were situations the audience could identify with. But another performance, in which he told a story about a conference he was invited to speak at, “didn’t work nearly as well.” It was the type of situation, Gopnik suspects, with which few could relate. But the Moth helped his writing—not only in the types of stories he tells, but how he tells them. “The listener can’t turn the page back,” he explains. “It reminded me, at a time when I felt my stuff was getting a little too meandering, of the value of that kind of simplicity of approach, and that kind of linear storytelling.” TOP: Gopnik with his two kids, Luke and Olivia, in Central Park. BELOW: Olivia’s old imaginary friend was the subject of one of Gopnik’s most popular stories. 16 Ryerson review of journalism • Summer 2012 In Adam Gopnik’s wallet is a Canadian $5 bill—a “nostalgic image of national spirit” that depicts children playing hockey on a frozen pond. It’s a reminder of his youth in Montreal, watching hockey behind the school and playing hooky in the city’s underground malls. It is also the subject of one of his essays from Winter: Five Windows on the Season, one of his two books released last fall. He used myriad examples, from the lyrics of Joni Mitchell’s “River” to the inventor of the modern central heating system in England, to frame the historical context of the season. Anansi House Press packaged the essays together as a book, and Gopnik delivered them as a series of Massey Lectures for the CBC in five Canadian cities. In Angels and Ages, a relatively short 2009 book comparing Darwin and Lincoln, it wasn’t a question of who these men were but “what were they like?” He imagined Darwin, for example, would “frown and furrow his brow and make helpless embarrassed harrumphs” were he around to suffer our questions today. It’s a completely different approach from Gopnik’s usual fare, which, with a few small exceptions, is barely rooted in personal themes. Kennedy was amazed that Gopnik could link such seemingly disparate figures together. “But Adam has read enough to know he can make those kind of comparisons,” he says, “without putting himself at risk of being called an intellectual charlatan.” When the pair toured Canada for the Massey Lecture series, an incredulous Kennedy watched from across the aisle of their plane as his friend spread four research books across the tray table—on a flight that was barely an hour long. “I’m losing my hair, my memory, and probably my skills,” Gopnik jokes, “but my ability to read seems to get greater as I get older.” Indeed, over the course of an hour, he refer- Photographs: top BY Deborah Copaken Kogan; bottom BY Yvonne Brooks ences artists, intellectuals, and writers too many to count. One minute it’s National Hockey League commissioner Gary Bettman and the next, philosophers John Stuart Mill and Oswald Spengler. He doesn’t name them idly, but to back up an argument or make a point—categorical knowledge that he has been honing for years. He feels more comfortable calling himself an essayist these days, “one of the last of a vanishing kind.” Others go so far as to describe him as a polymath and a raconteur, practised and interested in a variety of areas. He plays the piano, and would love to become a songwriter, he admits, a hobby he is pursuing now (a musical adaptation of Through the Children’s Gate is in the works). He has written two children’s books, The King in the Window and The Steps Across the Water—the latter takes place in the supposedly fictional, sprawling, skyscraping city of U Nork. Despite his art history degree, he was never particularly artistic, and spent last spring learning to draw. “Jesus, you’re going to try and top me at that, too, are you?’” says New Yorker artist Bruce McCall with a laugh. “With his application, discipline, and imagination, he’ll probably end up being a better artist than me, too.” Adam Gopnik looks tired. It is a late fall morning in Toronto, his second book tour in less than a month. He’s on deadline. I’m the latest in a string of back-to-back meetings, and it’s not even 11 a.m. But while protestors occupy the park outside, Adam is occupied promoting his latest book, The Table Comes First. It’s a mix of past articles and original pieces, with a focus on “family, France, and the meaning of food.” There are personal anecdotes and tales sprinkled throughout, with his own family—or, more precisely, his mother’s Grand Marnier soufflé—driving much of the narrative. It follows a familiar Gopnik formula, but it’s still more Winter than Through the Children’s Gate. I ask about his shift away from the more traditional personal essays that buoyed his magazine fame. We’re a long way from “Quattrocento Baseball,” and the things he wrote about in his 20s are not what he writes about today. In response, he recites a line from the great Irish-American writer Frank O’Connor: “And anything that happened to me afterwards, I never felt the same about again.” To him, that’s the invisible last line to every essay he’s ever written. Essay writing requires a certain curiosity, a desire to learn. Writers should come out of the process knowing more than when they began. He couldn’t write about the same thing twice, even if he wanted to. The shift may not be conscious, but it’s necessary. “That was one body of work,” he says, “and this is another.” Luke, after all, is no longer the young wanderer of Luxembourg Gardens. The arrival of Olivia’s imaginary friend seems like eons ago. Now that his children are older, there are but two rules: no piercings below the belt and no bitter memoirs. That hasn’t stopped them from threatening the latter, however. They’ve even come up with titles, riffs on their father’s work. Olivia’s would be called The Other Side of the Gate, while Luke’s would be Ages and Ages. But if they didn’t want to have their lives written about, Gopnik jokes, they shouldn’t have been born to a writer. There’s a scene in Through the Children’s Gate in which Gopnik returns to New York. “This isn’t a true Gothic cathedral,” he complains about St. Patrick’s Cathedral. “There are such things, I’ve seen them, and this is just a…copy, a raw inflated thing thrown up in emulation of a far-off and distant thing! That Renaissance palazzo on Fifty-fourth Street is no Renaissance palazzo—it’s a cheap stage-set imitation!” But it soon becomes clear that the city remains unchanged—just perceived differently in light of recent experience. And it strikes me that his writing is the same. Not a cheap-set imitation, mind you; rather, he is still writing comic-sentimental essays, even if the scope and scale have changed. Readers can bemoan the departure, but he is still Adam Gopnik. Winter, Angels and Ages, and even The Table Comes First are different, but also the same—Gopnik amplified. “And now New York just looks like New York,” he writes: “Old as time, worn as Rome, mysterious as life.” His wife toys with the idea of moving to the Connecticut countryside, away from the bustle of city life. And he knows E.B. White lived much of his life on a farm in Maine. But Gopnik doubts he’ll ever truly leave. To be the “rococo, Jewish, city-bound, Canadian E.B. White”—his words—would make him extremely happy. “But,” he admits, “I don’t know that I’ve earned that.” ❰❱ Summer 2012 • Ryerson review of journalism 17