FARRELL, JAMES T. Dreaming Baseball, EDS. RON BRILEY

advertisement

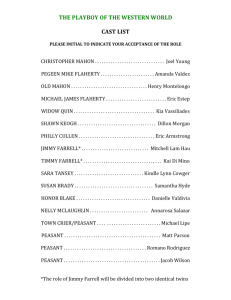

FARRELL, JAMES T. Dreaming Baseball, EDS. RON BRILEY, MARGARET DAVIDSON, AND JAMES BARBOUR. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2007. Pp. vii+316. $28.00 cb. Baseball history enthusiasts, Chicago history buffs, and avid readers of historic sports fiction will be both pleased and frustrated by the first-time publication of what the Kent State University Press dust jacket dramatically dubs the “‘lost novel’ about the 1919 Chicago Black Sox scandal” written by Chicago native James T. Farrell. In a succinct afterword, Dreaming Baseball co-editor Ron Briley explains how Farrell’s book proposal appealed in principle to publishing house A.S. Barnes in the late 1950s. Still, the untitled Farrell draft manuscript ultimately disappointed publisher John Lowell Pratt, who rejected the novel on the grounds of what Briley terms its “two dimensional” world. Discouraged by the unflattering reaction to the serious baseball novel meant to resurrect his career financially and artistically, Farrell, despite lukewarm interest from cronies in the publishing world, shelved the book. Nearly a half century later, Ron Briley, adjunct professor of history at the University of New Mexico-Valencia and a preparatory school headmaster, learned of the unpublished, unfinished baseball novel housed in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania as well as two additional, alternate drafts in the possession of Farrell estate executor, Cleo Paturis. Almost simultaneously and unbeknownst to Briley, scholar James Barbour made inquiries about publishing the “lost” novel only to learn from Farrell expert Donald Yanella that Briley had beat him to it. After some negotiation, scholars Briley, Barbour, and Barbour’s wife, Margaret Davidson, wisely joined forces. Sadly, however, the literary-archival adventure story of how editors Briley, Barbour, and Davidson reconciled competing drafts of the lengthy novel, replaced the euphemistic character pseudonyms with the real life surnames of the 1919 Black Soxers, and hashed out a title captivates as much or more than the novel itself, which continues to suffer from a “two dimensional” treatment. The action in Dreaming Baseball is narrated by fictional greenhorn Mickey Donovan, a Southside Chicago semi-pro prospect who gets called up to the “bigs” in time to witness the infamous 1919 Series from the Sox bench. Donovan is an amiable if not flat personality arguably based, according to editor Briley, on the real-life Freddie Linstrom, who the editors describe as a “boy wonder who came from the sandlots of Chicago.” Akin to The Great Gatsby in its world weary outlook, Dreaming Baseball is a coming of age, loss of innocence tale as told by the working-class Donovan, who struggles to make a career of the game he loves, court and wed his best gal, and stay true to his no-nonsense, widowed mother and the family’s humble Southside roots. JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY While Donovan’s voice, for all its atonality, captivates as well as lulls, the kid is an unlikely raconteur, as any nascent narrative insights are hampered by his youth, his Midwestern reserve, and his marginal status on the team, where he is dismissed initially as a “rookie,” a “goof ” and a “busher.” So utterly irrelevant is Donovan, a guiltless “Clean Sox” surrounded by wily, canny veterans, he is not even called upon to testify before the grand jury, nor interviewed by any of the major papers. Instead, he is left to reiterate to friends and family, ad nauseum and post hoc, the seemingly spurious, fleetingly-witnessed events that took place in the lobby of Cincinnati’s Sinton Hotel on the eve of the fateful 1919 Series, where the gamblers wore “know-it-all, hard, cynical looks on their faces . . . as if they didn’t see you or else looked right through you.” Put simply, Donovan, the ninteenyear-old second-baseman-in-waiting, is so blinkered by wide-eyed youth and big city lights that he makes a poor witness, in both the fictional and legal sense. While Donovan’s is a one-track baseball mind, he is, somehow, unable to shed new light on his infamous teammates, managers, and Sox owners. Not only does Farrell fail to make his loosely autobiographical stand-in worthy as a baseball yarn-spinner, he falls well short of making him a sympathetic character off the diamond, as Donovan proves unable, beyond the occasional hackneyed recital, to articulate his puppy love for the woman who will become his wife, Mary Collins. Dreaming Baseball’s narrator turns its back on even the most tried and true baseball stock characters; Mickey, for example, is neither the baseballobsessed zealot-mystic nor the hard-partying, caution-to-the-wind playboy—both types typically granted license by readers—but a young man caught in between, anxious and inarticulate. A host of other problems plague Farrell’s unfinished novel, including many needless redundancies, a problematic, misdirection of a first chapter, and a conventional, almost obligatory chronicling of events that reads more like a deposition than a reclamation or revivification. While the editors are to be congratulated for their heroic, painstaking efforts to condense more than 500 manuscript pages into a digestible 300-page novel, they might have gone further, as several passages in the book feature embarrassing, almost verbatim repetitions of the kind typically weeded out early in the editorial process. In his afterword, editor Briley claims, “This is neither a critical edition nor a facsimile edition of Farrell’s work but, rather, a new work of fiction we are introducing to a contemporary audience.” Though the sentiment expressed here is genuine and carefully reasoned, its premise seems fanciful, as, in the first case, Dreaming Baseball would not make muster as a conventional, mass market novel in 2007, just as it failed to in 1958, and would be dead in the water without the benefit of Farrell’s growing, posthumous reputation among scholars of sport and literature. Other small quibbles include the title of the book, Dreaming Baseball, which the editors take great pains to defend on thematic grounds but which, in its revisionist, post-modern feel, bears little resemblance to the titles of Farrell’s more than two dozen other novels. Also problematic is the poor quality author photograph on the back jacket which, doubtless enhanced from a low resolution newspaper photo, gives the appearance of having been selectively darkened to the point of caricature. Finally, the design of the book perplexes, as the front cover, while handsomely, dreamily designed, fails to list the book’s three editors, while it inadvertently misrepresents the book by the longdead Farrell as “A new novel by the author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy.” Though Eliot 488 Volume 34, Number 3 REVIEWS: BOOKS Asinof, who knew Farrell and benefited from his reminiscences in writing the definitive Eight Men Out, provides a mostly descriptive foreword to the book, the editor’s afterword would be better deployed as a general introduction explaining the book’s complicated past and present. As it is, it is possible, indeed likely, that unfamiliar readers will finish the book before realizing it has been doctored. In the end, Kent State University Press and editors Briley, Davidson, and Barbour deserve much credit for seeing this forgotten book through to publication, as it provides a valuable, historical window to early Jazz Age Chicago and a rare, albeit brief, account of the struggling White Sox in the years after the eight man ban. While it is natural to wish this too-long-mothballed book a wide and appreciative audience, it seems destined for relatively few scholars and historical curiosity seekers. —MICHAEL JACK ZACHARY North Central College Fall 2007 489