bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

advertisement

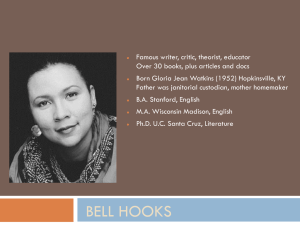

bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Search bell hooks From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents Gloria Jean Watkins (born September 25, 1952), better Featured content known by her pen name bell hooks,[1][2] is an American author, feminist, and social activist. Her writing has focused on the interconnectivity of race, class, and gender and their ability to produce and perpetuate systems of oppression and domination. She has published over thirty books and numerous scholarly and mainstream articles, appeared in several documentary films and participated in various public lectures. Primarily through a postmodern perspective, hooks has addressed race, class, and gender in education, art, history, sexuality, mass media and feminism. Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia bell hooks Born Gloria Jean Watkins September 25, 1952 (age 58) Hopkinsville, Kentucky, USA Pen name bell hooks Toolbox Contents [hide] Print/export Languages Deutsch 1 Biography 1.1 Early life 1.2 Career Ελληνικά 2 Influences Español 3 Teaching to Transgress Français 4 Criticism Bahasa Indonesia 5 Awards and nominations עברית 6 Select bibliography 日本語 7 Film appearances Polski 8 Further reading Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски 9 References Occupation Author, feminist, social activist Notable work(s) Influences Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism All About Love: New Visions We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity [show] 10 External links Svenska Türkçe Biography [edit] Early life [edit] Gloria Jean Watkins was born on September 25, 1952 in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. She grew up in a working class family with five sisters and one brother. Her father, Veodis Watkins, was a custodian and her mother, Rosa Bell Watkins, was a homemaker. Throughout her childhood, she was an avid reader. Her early education took place in racially segregated public schools, and she wrote of great adversities when making the transition to an integrated school, where teachers and students were predominantly white. She graduated from Hopkinsville High School in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, earned her B.A. in English from Stanford University in 1973 and her M.A. in English from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1976. In 1983, after several years of teaching and writing, she completed her http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia doctorate in the literature department from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a dissertation on author Toni Morrison. Career [edit] Her teaching career began in 1976 as an English professor and senior lecturer in Ethnic Studies at the University of Southern California. During her three years there, Golemics (Los Angeles) released her first published work, a chapbook of poems titled "And There We Wept" (1978), written under her pen name, "bell hooks". She adopted her grandmother's name as her pen name because her grandmother "was known for her snappy and bold tongue, which [she] greatly admired." She put the name in lowercase letters "to distinguish [herself] from her grandmother." Her name's unconventional lowercasing signifies what is most important in her works: the "substance of books, not who I am." [3] She taught at several post-secondary institutions in the early 1980s, including the University of California, Santa Cruz and San Francisco State University. South End Press (Boston) published her first major work, Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism in 1981, though it was written years earlier, while she was an undergraduate student. [4] In the decades since its publication, Ain't I a Woman? has gained widespread recognition as an influential contribution to postmodern feminist thought.[5] Ain’t I a Woman? examines several recurring themes in her later work: the historical impact of sexism and racism on black women, devaluation of black womanhood, media roles and portrayal, the education system, the idea of a white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy, the marginalization of black women, and the disregard for issues of race and class within feminism. Since the publication of Ain’t I a Woman?, she has become eminent as a leftist and postmodern political thinker and cultural critic. She targets and appeals to a broad audience by presenting her work in a variety of media using various writing and speaking styles. As well as having written books, she has published in numerous scholarly and mainstream magazines, lectures at widely accessible venues, and appears in various documentaries. She is frequently cited by feminists as having provided the best solution to the difficulty of defining something as diverse as "feminism", addressing the problem that if feminism can mean everything, it means nothing. She asserts an answer to the question "what is feminism?" that she says is "rooted in neither fear nor fantasy... 'Feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression'". [6] She has published more than 30 books, ranging in topics from black men, patriarchy and masculinity to self-help, engaged pedagogy to personal memoirs, and sexuality (in regards to feminism and politics of aesthetic/visual culture). A prevalent theme in her most recent writing is the community and communion, the ability of loving communities to overcome race, class, and gender inequalities. In three conventional books and four children's books, she demonstrates that communication and literacy (the ability to read, write, and think critically) are crucial to developing healthy communities and relationships that are not marred by race, class, or gender inequalities. She has held positions as Professor of African and African-American Studies and English at Yale University, Associate Professor of Women’s Studies and American Literature at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and as Distinguished Lecturer of English Literature at the City College of New York. A commencement speech hooks gave in 2002 at Southwestern University was considered controversial. Eschewing the congratulatory mode of traditional commencement speeches, she spoke of government-sanctioned violence and oppression, and admonished students who went with the flow. The speech was booed by many in the audience, though "several graduates passed over the provost to shake her hand or give her a hug."[7] In 2004 she joined forces with Berea College in Berea, Kentucky as Distinguished Professor in Residence, [8] where she participated in a weekly feminist discussion group, "Monday Night http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Feminism", a luncheon lecture series, "Peanut Butter and Gender" and a seminar, "Building Beloved Community: The Practice of Impartial Love". Her most recent book is entitled belonging: a culture of place, which includes a very candid interview with author Wendell Berry as well as a discussion of her move back to Kentucky. Influences [edit] Writers who have influenced hooks include abolitionist and feminist Sojourner Truth (whose speech Ain't I a Woman? inspired her first major work), Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (whose perspectives on education she embraces in her theory of engaged pedagogy), Peruvian theologian and Dominican priest Gustavo Gutierrez, psychologist Erich Fromm, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, writer James Baldwin, Guyanese historian Walter Rodney, black nationalist leader Malcolm X, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr (who addresses how the strength of love unites communities).[9][10] Teaching to Transgress [edit] This section may require copy-editing. In her book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, hooks investigated the classroom as a seat of constraint and yet also as a potential locus for liberation. This pattern showed that the teacher has the currency of knowledge and deposits it into the students’ minds where it is left and took off at a further time. [vague] Against this pedagogy, she argued that the routine of control and the inappropriate exercise of power often enhance the dynamic of the powerful teacher and dull the enthusiasm, objectified students in class. [vague] This situation leads to most students’ lessons being obedience to authority. As she writes: “Those boundaries that would confine each pupil to a rote, assembly-line approach to learning.” [11] She advocated that the university should instead encourage students and teachers to transgress. She looked for a way to use collective effort to make learning more relaxing and exciting. She described teaching as serving “as a catalyst that calls everyone to become more and more engaged…”. [12] Since she had to enter the classroom as a total individual, she realized that authority and experience can exclude and silence students, and that the teacher had to disperse the students’ attention from her voice.[vague] At the same time, she recognized that decentralization of authority would match revolt from students.[vague] What she advocates pedagogically contributes to the model education system. Criticism [edit] She has attracted a measure of criticism, often from conservative writers. Peter Schweizer has accused her of hypocrisy in sexual politics.[13] One passage writer David Horowitz has specifically objected to is a discussion in the first chapter of Killing Rage, in which she states that she is "sitting beside an anonymous white male that [she] long[s] to murder". [14] She explains that her impulse was occasioned by a ticket/boarding pass error resulting in the harassment of her black, female friend; she sees this dispute as symbolic of the role of racism and sexism in American society. Awards and nominations Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics: The American Book Awards/ Before Columbus Foundation Award (1991) Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism: "One of the twenty most influential women’s books in the last 20 years" by Publishers Weekly (1992) bell hooks: The Writer’s Award from the Lila Wallace–Reader’s Digest Fund (1994) Happy to Be Nappy: NAACP Image Award nominee (2001) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] [edit] bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Homemade Love: The Bank Street College Children's Book of the Year (2002) Salvation: Black People and Love: Hurston Wright Legacy Award nominee (2002) bell hooks: Utne Reader's "100 Visionaries Who Could Change Your Life" bell hooks: The Atlantic Monthly's "One of our nation’s leading public intellectuals" Select bibliography [edit] Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism (1981) ISBN 0-89608-129-X All About Love: New Visions (2000) ISBN 0-06-095947-9 And There We Wept: Poems. (1978). OCLC 6230231 . Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (1995) ISBN 1-56584-263-4 Be Boy Buzz (2002) ISBN 0-7868-0814-4 Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992) ISBN 0-89608-433-7 Bone Black: memories of girlhood (1996) ISBN 0-8050-5512-6 Breaking Bread: Insurgent Black Intellectual Life (1991) (with Cornel West) ISBN 0-89608-414-0 Communion: The Female Search for Love (2002) ISBN 0-06-093829-3 Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (2000) ISBN 0-89608-629-1 Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984) ISBN 0-89608-614-3 Happy to be Nappy (1999) ISBN 0-7868-0427-0 Homemade Love (2002) ISBN 0-7868-0643-5 Justice: Childhood Love Lessons (2000). ISBN 0688168442. OCLC 41606283 . Killing Rage: Ending Racism (1995) ISBN 0-8050-5027-2 Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations (1994) ISBN 0-415-90811-6 Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies (1996) . ISBN 0415918235. OCLC 35229108 . Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work (1999) ISBN 0-8050-5910-5 Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-esteem (2003) ISBN 0-7434-5605-X Salvation: Black People and Love (2001) ISBN 0-06-095949-5 Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-recovery (1993) ISBN 1-896357-99-7 Skin Again (2004) ISBN 0-7868-0825-X Soul Sister: Women, Friendship, and Fulfillment (2005) ISBN 0-89608-735-2 Space (2004) ISBN 0-415-96816-X Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (1989) ISBN 0-921284-09-8 Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (2003) ISBN 0-415-96817-8 Teaching to Transgress: Education As the Practice of Freedom (1994) ISBN 0-415-90808-6 We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity(2004) ISBN 0-415-96926-3 Where We Stand: Class Matters (2000) ISBN 9780415929134 The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (2003) ISBN 0-7434-5607-6 Witness (2006) ISBN 0-89608-759-X Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life (1997) ISBN 0-8050-5722-6 Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (1990) ISBN 0-921284-34-9 ″Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom‘’ (2010) ISBN 0-978-0-415-96820-1 Film appearances Black Is... Black Ain't (1994) Give a Damn Again (1995) Cultural Criticism and Transformation (1997) My Feminism (1997) I Am a Man: Black Masculinity in America (2004) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] [edit] bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Voices of Power (1999) Baadasssss Cinema (2002) Writing About a Revolution: A Talk (2004) Happy to Be Nappy and Other Stories of Me (2004) Is Feminism Dead? (2004) Further reading [edit] Florence, Namulundah. bell hooks's Engaged Pedagogy. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1998. ISBN 0-89789-564-9 . OCLC 38239473 . Leitch et al., eds. "Bell Hooks." The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001. pages 2475-2484. ISBN 0-393-97429-4 . OCLC 45023141 . South End Press Collective, eds. "Critical Consciousness for Political Resistance"Talking About a Revolution.Cambridge: South End Press, 1998. 39-52. ISBN 0-89608-587-2 . OCLC 38566253 . Stanley, Sandra Kumamoto, ed. Other Sisterhoods: Literary Theory and U.S. Women of Color. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998. ISBN 0-252-02361-7 . OCLC 36446785 . Wallace, Michelle. Black Popular Culture. New York: The New Press, 1998. ISBN 1-56584-459-9 . OCLC 40548914 . Whitson, Kathy J. (2004). Encyclopedia of Feminist Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313327319. OCLC 54529420 . References [edit] 1. ^ hooks, bell, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (South End Press, 1989) ISBN 0896083527 2. ^ Dinitia Smith (2006-09-28). "Tough arbiter on the web has guidance for writers" . The New York Times: p. E3. "But the Chicago Manual says it is not all right to capitalize the name of the writer bell hooks because she insists that it be lower case." 3. ^ Heather Williams. "bell hooks Speaks Up" . The Sandspur (2/10/06). Retrieved 2006-0910. 4. ^ Teaching to Transgress, 52. 5. ^ Google Scholar shows 894 citations of Ain't I a Woman (as of August 30, 2006) 6. ^ bell hooks, Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics Pluto Press, 2000 7. ^ The Austin Chronicle: News: Hooks Digs In 8. ^ Berea.edu 9. ^ Notes on IAPL 2001 Keynote Speaker, bell hooks 10. ^ Building a Community of Love, bell hooks & Thich Nhat Hanh 11. ^ (hooks, Teaching to Transgress 12) 12. ^ (hooks, 11) 13. ^ Do As I Say (Not As I Do): Profiles in Liberal Hypocrisy, Peter Schweizer, Doubleday, 2005, p.9 . ISBN 0385513496. OCLC 62110441 . 14. ^ hooks, bell. Killing Rage, p. 8. Henry Holt & Co. New York, NY. 1995 . ISBN 0805037829. OCLC 32089130 . External links [edit] Ejournal website hooks) (several critical resources for bell Real Change News Royale) (interview with hooks by Rosette Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: bell hooks bell hooks articles published in Shambhala Sun Magazine South End Press (books by hooks published by South End Press) University of California, Santa Barbara "Postmodern Blackness" Whole Terrain (biographical sketch of hooks) (article by hooks) (articles by hooks published in Whole Terrain) Z Magazine - Challenging Capitalism & Patriarchy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] (interviews with hooks by Third World bell hooks - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Viewpoint) Ingredients of Love bell hooks (an interview with ascent magazine) at the Internet Movie Database Categories: 1952 births | African American philosophers | African American writers | American activists | American feminists | Anti-poverty advocates | Feminist studies scholars | American feminist writers | Living people | Stanford University alumni | University of California, Santa Cruz alumni | City University of New York faculty | University of Southern California faculty | San Francisco State University faculty | Yale University faculty | People from Hopkinsville, Kentucky | African American studies scholars | Black feminism | University of Wisconsin–Madison alumni | Lowercase proper names or pseudonyms This page was last modified on 18 April 2011 at 06:28. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Contact us Privacy policy About Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_hooks[4/25/2011 9:22:59 AM] Disclaimers