Image Quiz 8 - Nephro

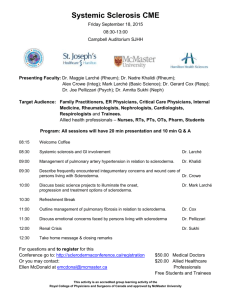

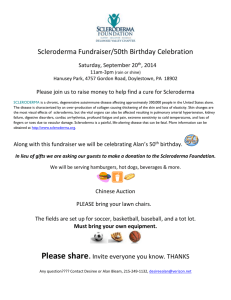

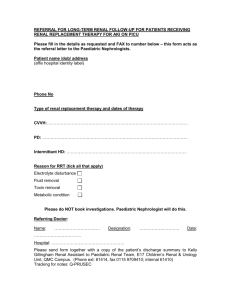

advertisement

www.nephro-pathology.com CASE OF THE WEEK 10 & IMAGE QUIZ 8 CLINICAL HISTORY: 31 year old female, presented with joint pains, oral ulcers, dysphagia and uncontrolled hypertension since 3 months. History of skin rashes few months back for which Dermatological consultation was sought and steroids were instituted. EXAMINATION: No edema, BP 200/120 mmHg INVESTIGATIONS: Urine – Albumin: nil, RBC- 2-3/hpf, WBC 4-6/hpf. Haematological profile -Haemoglobin 7.5 g% (75 g/L) , ESR 88 mm/ 1st hour Urea: 116 mg% (41.41 mmol/L), Creatinine 3.1 mg% (274 micro mol/L) ANA- positive (1:640) anti ds DNA negative pANCA , cANCA: negative, anti-histone and anti RNA Polymerase antibodies (I, II, III): + Serum C3 & C4 levels: WNL, HBsAg/HIV/HCV- negative USG abdomen: Bilateral normal sized kidneys (9.1 and 9.4 cms) with raised cortical echogenicity Clinical impression: Connective tissue disorder (? MCTD) RENAL BIOPSY www.nephro-pathology.com Scanner view images reveal tubulointerstitial scarring, glomeruli with wrinkled capillaries and arteries showing marked fibrointimal thickening & narrowing of lumina. www.nephro-pathology.com Glomeruli show ischemic wrinkling and “pseudothickening” of capillaries with retraction of the glomerular tuft www.nephro-pathology.com www.nephro-pathology.com Arteries show circumferential medial proliferation with “onion skinning”, subintimal edema, endothelial swelling and variable compromise and occlusion of arterial lumina. DIF (IMAGE QUIZ 8) www.nephro-pathology.com IgG IgG www.nephro-pathology.com IgG IgG The DIF studies showed negativity for IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, C1q and Kappa & Lambda light chains in the glomeruli. Intense nuclear staning for IgG was however noted for IgG (and kappa & lambda light chains) in the tubular epithelial cell nuclei, vascular smooth muscle cell nuclei, endothelial cells and podocyte nuclei (consistent with the “ tissue ANA” phenomenon in the present clinical setting). FINAL DIAGNOSIS Scleroderma Renal Crisis with histological features suggestive of a thrombotic microangiopathy “ Tissue ANA phenomenon” in DIF studies DISCUSSION: Systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) is a connective tissue disease associated with autoimmunity, vasculopathy, and fibrosis [1]. Clinically ,systemic sclerosis can manifest as as limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous forms and rarely as systemic sclerosis sine Scleroderma. It can also be a part of Mixed connective tissue disorders (e.g Systemic sclerosis, SLE and polymyositis) or overlap syndrome (e.g.systemic sclerosis with SLE, rheumatoid arthritis or polymyositis). Apart from cutaneous manifestations, sytemic sclerosis can affect various organ systems including the gastrointestinal system (Bacterial overgrowth, Barrett esophagus or strictures, Gastric antral vascular ectasias: watermelon stomach, or Gastroesophageal reflux disease), Cardiovascular system (Abnormal cardiac conduction, Congestive heart failure, Diastolic dysfunction,Pericardial effusion, Digital ischemic changes and Raynaud phenomenon), musculoskeletal system (Flexion contractures Muscle atrophy), Pulmonary system (Interstitial lung disease, Pulmonary arterial hypertension) and renal system. Renal involvement in sytemic sclerosis usually ocurs in about 5-10% of patients, usually in the form of Scleroderma renal crisis (SRC) in patients with diffuse cutaneous form of the disease [2]. SRC is typically characterized by a sudden and marked increase in systemic blood pressure, and acute renal failure, with or without significant microangiopathic hemolytic anemia or thrombocytopenia. SRC is often accompanied by headache, blurring of vision, and dyspnea. These symptoms can be attributed to hypertensive encephalopathy, congestive heart failure, and/or pulmonary edema consequent to rapid increase in blood pressure[3]. Pathogenesis of SRC is uncertain but possibly involves endothelial injury as the triggering event which triggers a series of events and a vicious cycle involveing the renin-angiotensin system culminating in malignant hypertension and characteritic picture of SRC [4] Histologically, features are usually of a thrombotic microangiopathy. Similar to idiopathic malignant hypertension, and in contrast to haemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, primary small vessel changes usually predominate over glomerular alterations. Early vascular changes can manifest as intimal accumulation of myxoid material, thrombosis and/or fibrinoid necrosis. Onion-skin lesions usually develop later while fibrointimal sclerosis with or without adventitial fibrosis may be the only manifestation of chronic persistent damage or sequel of previous acute episodes. Acute glomerular changes can occur primarily or often develop secondary to the vascular injury and reduction in renal perfusion DIF and ultrastructural studies do not reveal any unique findings. Few cases of MCTD /Scleroderma or other connective tissue disorders (including SLE) with high titres of ANA may show the “tissue ANA phenomenon” where the anti-nuclear antibodies (usually of IgG subtype) bind in a specific “granular / speckled” pattern to tissue nuclear antigens and produce the characteristic fluorescence in DIF studies [5,6]. Major risk factors for development of SRC include the diffuse cutaneous form of the disease, rapidly progressive skin disease and high dose corticosteroid therapy [3, 7, 8]. Other risk factors for SRC include anaemia, HRT, pericardial effusion, cardiac insufficiency, high skin score and large joint contractures, the presence of antibodies to RNA polymerases (particularly RNA polymerases I and III) and new cardiac events [7,8,9]. Before the advent of ACE inhibitors, SRC was associated with a poor renal outcome, progressing to ESRD in majority of patients. However these drugs have significantly reduced the adverse renal outcome, particularly if disease is recognized and treatment initiated early [10,11,12] REFERENCES: 1. Sakkas LI. New developments in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity. 2005 Mar;38(2):113-6. 2.C. P. Denton, G. Lapadula, L. Mouthon,U. Mu¨ ller-Ladner. Renal complications and scleroderma renal crisis. Rheumatology 2009;48:iii32–iii35 3.Penn H, Denton CP.Diagnosis, management and prevention of scleroderma renal disease.Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008 Nov;20(6):692-6. 4. Virginia D. Steen. Scleroderma renal crisis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 29 (2003) 315–333 5. Denton CP, Black CM. Scleroderma – clinical and pathological advances. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004;18:271–90. 6. Ibrahim Batal,Robyn T. Domsic, Thomas A.Medsger Jr., and Sheldon Bastacky. Scleroderma Renal Crisis: A Pathology Perspective. International Journal of Rheumatology. Volume 2010, Article ID 543704, 7 pages doi:10.1155/2010/543704 7. Teixeira L, Mouthon L, Mahr A et al. Mortality and risk factors of scleroderma renal crisis: a French retrospective study in 50 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:110–6. 8. Bryan C, Howard Y, Brennan P et al. Survival following the onset of scleroderma: results from a retrospective inception cohort study of the UK patient population. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:1122–6. 9.DeMarco PJ, Weisman MH, Seibold JR et al. Predictors and outcome of scleroderma renal crisis: the high-dose versus low-dose D-penicillamine in early diffuse systemic sclerosis trial. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2983–9. 10. Lopez-Ovejero JA, Saal SD, D’Angelo WA, et al. Reversal of vascular and renal crises of scleroderma by oral angiotensin-converting-enzyme blockade. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1417 – 9. 11.Thurm RH, Alexander JC. Captopril in the treatment of scleroderma renal crisis. Arch Intern Med 1984;144:733–5. 12. Zawada Jr ET, Clements PJ, Furst DA, et al. Clinical course of patients with scleroderma renal crisis treated with captopril. Nephron 1981;27:74 – 8. © www.nephro-pathology.com