First mover advantages in international business and firm

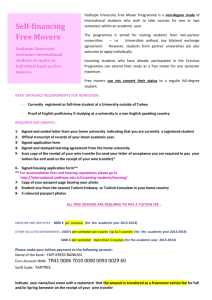

advertisement