A Mariner's Life - Lake Champlain Maritime Museum

advertisement

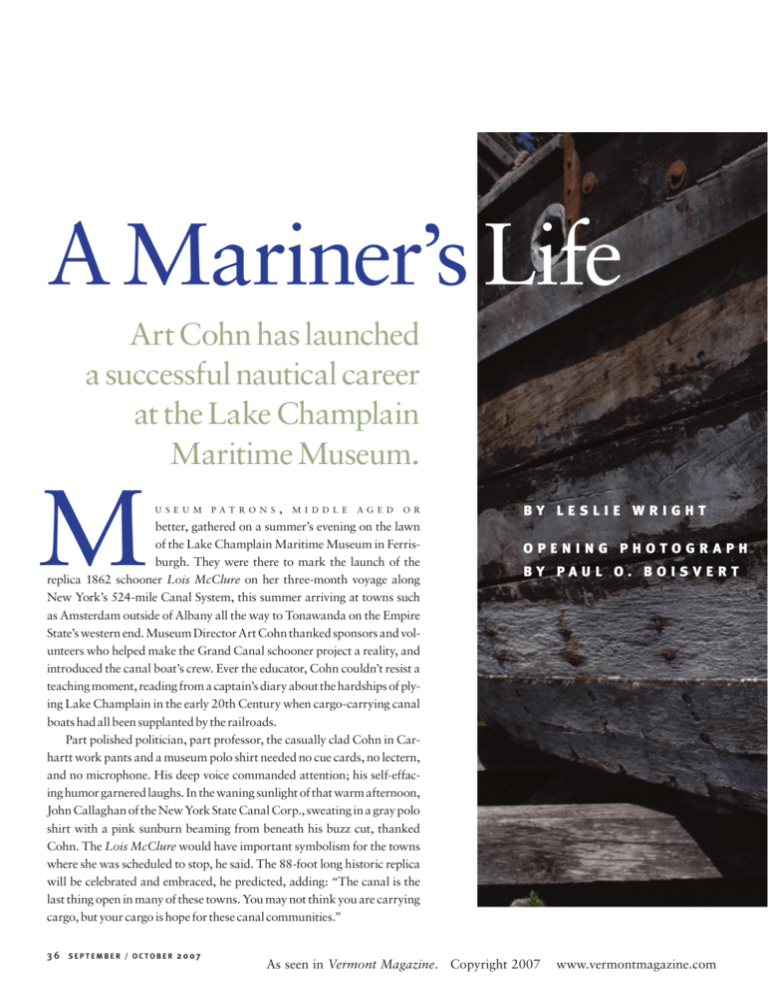

A Mariner’s Life Art Cohn has launched a successful nautical career at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. M pat ron s , m i d dl e ag e d o r better, gathered on a summer’s evening on the lawn of the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in Ferrisburgh. They were there to mark the launch of the replica 1862 schooner Lois McClure on her three-month voyage along New York’s 524-mile Canal System, this summer arriving at towns such as Amsterdam outside of Albany all the way to Tonawanda on the Empire State’s western end. Museum Director Art Cohn thanked sponsors and volunteers who helped make the Grand Canal schooner project a reality, and introduced the canal boat’s crew. Ever the educator, Cohn couldn’t resist a teaching moment, reading from a captain’s diary about the hardships of plying Lake Champlain in the early 20th Century when cargo-carrying canal boats had all been supplanted by the railroads. Part polished politician, part professor, the casually clad Cohn in Carhartt work pants and a museum polo shirt needed no cue cards, no lectern, and no microphone. His deep voice commanded attention; his self-effacing humor garnered laughs. In the waning sunlight of that warm afternoon, John Callaghan of the New York State Canal Corp., sweating in a gray polo shirt with a pink sunburn beaming from beneath his buzz cut, thanked Cohn. The Lois McClure would have important symbolism for the towns where she was scheduled to stop, he said. The 88-foot long historic replica will be celebrated and embraced, he predicted, adding: “The canal is the last thing open in many of these towns. You may not think you are carrying cargo, but your cargo is hope for these canal communities.” 36 u s e u m september / october 200 7 By Leslie Wright opening Photograph by Paul O. Boisvert As seen in Vermont Magazine. Copyright 2007 www.vermontmagazine.com As seen in Vermont Magazine. Copyright 2007 www.vermontmagazine.com V e r m o n t M a g a z i n e 3 7 ing baritone with a roughness at the edges that hints at his urban upbringing. Cohn’s close-cropped beard is sprinkled with gray. A silver Bermudian coin hangs from his neck—the coin’s edges have been cut away to leave just the image of a fish. photo: courte s y of L a ke Champlain M aritime Museum A When he’s not at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in Ferrisburgh, Art Cohn may be out diving the lake or at the helm of the Lois McClure. Callaghan’s comments spoke to the museum’s mission and captured the essence of Art Cohn, the 57-year-old underwater explorer, educator, and researcher who has been on a three-decade-long odyssey to protect Lake Champlain’s submerged cultural resources. Cohn has made it his life’s work to share his boundless enthusiasm for an underwater world most of us will never see and historic events in Champlain’s past—all the while leading a loyal crew of followers. A cargo of hope, indeed. The Lois McClure project is just one example. “The mission hasn’t changed from day one,” Cohn told his audience at the canal boat launch this past June. “It’s to share the rich archeological history of the lake and share it with the public.” Cohn founded the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum 22 years ago, in Ferrisburgh. Bob Beach, owner of neighboring Basin Harbor Club, was instrumental in starting the museum, as well. Cohn is surrounded by a tight group of long-time 38 september / october 200 7 supporters and employees, but more than anyone else he has been the captain of underwater historic preservation on Lake Champlain. Without Cohn we’d know a lot less about the lake and its rich history, long-time lake historian Peter Barranco says. “Art’s been a driving force in his field. His dedication to it. His understanding of it,” Barranco says. “He’s been able to convey very well the importance of the lake and its history to the public.” Had Cohn been born in another time, he might have been a scrappy and resourceful Revolutionary War general on the American side capitalizing on his charisma to motivate tired, hungry, and ill-prepared troops to stay the course against tall odds. Or perhaps he would have been a swashbuckling pirate leading a dedicated but disheveled outlaw crew on the high seas. In any case, Cohn is a leader. It’s not hard to imagine a past life for him as a mariner. Tall and broad shouldered, he speaks in a boom- rt cohn grew up in the New York City borough of Queens. His father was a pharmaceutical salesman and his grandfather owned a drug store, where Cohn worked as a kid. His introduction to diving came in his teens in the murky waters of greater New York Harbor. Fresh out of law school in the early 1970s, Cohn started his career as a public defender in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. He soon shelved the law and found work as a diver and dive instructor in Vermont and the Caribbean. In Vermont, he was employed by a dive shop in downtown Burlington. That was where the hand of fate interceded. A ferryboat captain stopped in the dive shop one day and queried Cohn about some of the wrecks at the bottom of the lake. Cohn didn’t know about the wrecks. Few people did back in the 1970s. The man was Capt. Merritt Carpenter. On his runs across the widest part of the lake from Burlington to Port Kent, N.Y., he had plenty of time to ponder the lake and its history. The captain knew of several wrecks. The General Butler was a canal boat that sank off the Burlington breakwater in 1876. The Phoenix, a steamer, burned in 1819. But the captain didn’t dive. He had no proof the wrecks were there, though he had done enough research to make fairly educated guesses. Cohn was intrigued. Sadly, the earlier history of Champlain shipwrecks was marred by tales of boats being raised only to face destruction because their salvagers either lacked finances or an understanding of how to preserve the wrecks. Cohn was mindful of that unfortunate history and points out that misconceptions persist even today. “Submerged cultural resources are so new as a class of resource that usually people don’t have the slightest idea of what you are talking about when you start talking about a shipwreck as underwater cultural heritage,” Cohn says. “‘What is that? They are just shipwrecks, right? You just rip them out of the bottom and sell them at auction and put the pieces around your neck.’” Cohn helped shed light on the value of these hidden treasures. In the 1980s, he As seen in Vermont Magazine. Copyright 2007 www.vermontmagazine.com photo: paul o. boisvert played a key role in the creation of the Lake Champlain Underwater Historic Preserve, a collection of nine wrecks open for viewing by divers. More recently, Cohn advocated on an international stage as a U.S. delegate to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s convention for the protection of underwater cultural heritage. His voice balanced that of the salvage operators who raise underwater artifacts for profit. Meanwhile, the Maritime Museum’s own preservationist role has been put to the test right here in Lake Champlain. A decade ago, while mapping the lake bottom using side-scan sonar, the museum’s research team made a monumental find—a missing gunboat that was part of Benedict Arnold’s fleet in the Battle of Valcour Island in 1776. The gunboat’s location has remained a secret while a number of players with a potential stake in the discovery—including Senators Patrick Leahy of Vermont and Hillary Clinton of New York, the U.S. Navy, and the Department of Defense— determine the best course of action. Cohn’s not frustrated that it’s tak- ing longer than a decade to decide what to do with the gunboat. It’s been there a long time—when he dove on the site, he was the first person to see the boat, named the Spitfire, since it sank in October 1776. “There are a lot of very good examples about bad recovery and part of what we’re trying to do is learn from that,” Cohn says. “The biggest single mistake that these various bad case studies have made is hasty judgment governed by politics or economics as opposed to what’s best for the shipwreck.” In a sense, Cohn’s entire career prepared him for the complex and weighty matter of deciding the fate of one of the lake’s most significant cultural finds in recent history. He’s been doing what’s best for the lake’s shipwrecks since Capt. Carpenter sensed something about Cohn and entrusted him with information about the location of certain shipwrecks in Lake Champlain. Cohn continues to take that responsibility to heart. Callaghan, the official who thanked Cohn for bringing the Lois McClure down the Erie Canal, felt it when he spoke of bringing hope to disenfranchised communities. Len Ruth felt it when Cohn gave him a job 18 years ago. As seen in Vermont Magazine. Copyright 2007 www.vermontmagazine.com Ruth was a troubled kid from Ticonderoga, N.Y. when a judge sent him to job training in Vergennes. The museum has had a longstanding relationship with the Job Corps and Ruth was introduced to the museum through a boat-building program. “I could have continued to be a delinquent. Art gave me a chance and an opportunity and I’m extremely grateful for that,” says Ruth who, as bosun, keeps the Lois McClure in order. Erick Tichonuk, who is an underwater archaeologist and coordinator of the museum’s replica fleet, has been with the museum since its inception. He calls Cohn a mentor, summing up what drives Cohn. “Art has a real care for society and culture as a whole,” Tichonuk says. “He wants to make the world or his corner of it a better place.” That is Art Cohn’s cargo of hope. Leslie Wright is a freelance writer who lives in Ferrisburgh. For more information on Art Cohn’s work and the Lake Champlain Maritime Musuem, go to www.lcmm.org or call (802) 475-2022. The Lois McClure will return to Basin Harbor in Vermont from September 24 to October 14. V e r m o n t M a g a z i n e 3 9