SOCIAL MARKETING: UNRAVELING THE "FUZZY" PRODUCT

advertisement

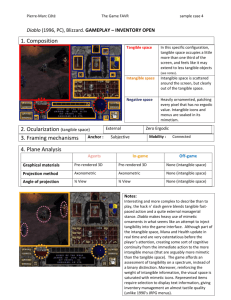

SOCIAL MARKETING: UNRAVELING THE "FUZZY" PRODUCT Marie-Louise Fry University of Newcastle NSW 2308 Associate Professor Susan Dann Queensland University of Technology Abstract Although social marketing is recognised as being difficult to define, it remains a major growth area in the discipline of marketing. Ambiguity surrounding social marketing can, in part, be attributed to the fuzzy and elusive nature of the 'idea' product. This paper develops a product classification which recognises fundamental differences between goods, services and 'idea' product types. From a marketing perspective, as both the close of the millennium draws near and the application of social marketing expands, distinctions need to be drawn between the varying product types to provide greater clarity and more in-depth understanding to the area of social marketing. Introduction Since the issue of distinguishing social marketing as a subset of marketing was first raised some 30 years ago, marketing scholars have debated the inclusion of ideas within the exchange relationship and how, as products, they differ from physical goods and services (Bagozzi 1975; Kotler & Levy 1969; Kotler 1972). During this time, social marketing has developed from the simple concept of broadening marketing's tools, to selling changes in ideas and behaviours, to becoming a social change management technology (Kolter & Roberto 1989; Andreasen 1995; Goldberg et al 1997). While social marketing refers to an 'adaptation' of commercial marketing technologies, there is little examination of social marketing beyond the broad application of marketing tools and technologies to a social context. Consequently, social marketing campaigns may not have achieved the full depth and breadth of activities that are characterised in traditional product and service marketing situations. One reason for this may be due to broadening the market penetration of social marketing to various areas such as health, environment and education, as well as promoting the adoption of social marketing to a wide range of private, public and non-profit organisations. As social marketing has achieved acceptance, it is now time to deepen the social marketing discipline by developing more sophisticated concepts and tools. This paper develops a framework to explore one of the 4p's - the product - to ascertain it's identity in a social marketing context, as distinct from those of goods and services. An attempt is made to define and clarify some essential elements for developing a conceptual understanding of the social product. While public policy frequently deals with social marketing issues, social marketing activities may be undertaken by a diverse range of groups. As such, this article focuses on defining social marketing products more broadly, not solely within a public policy context. Unraveling the "FUZZY" Social Product 1 Conceptually marketing is based on the notion of exchange. By accepting intangible products (ie. services) within the exchange context (Kotler & Levy 1969; Kotler 1972; Bagozzi 1975, AMA 1985) the inclusion of intangible psychological entities, such as ideas, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours becomes possible in the definition of what can and does constitute a marketing "product". The physique of products can be tangible (palpable) or intangible (impalpable), or more commonly combinations of both. While the social marketing product certainly fits within the intangible product dimension, it is the degree and nature of the intangibility surrounding the social product that is at issue. The social product Defining the social product has evolved over time. Fine (1981) viewed the social product from its point of conception, as an individual idea diffusing, in time, to become social issues and causes as they catch on. The sum of these individual ideas over time change individual actions to achieve direct or indirect social benefits. Conversely, Lovelock (1979) conceived the social product as the outcomes of organisations that promote or advocate ideas and social causes, using the term "social behaviours" to refer to the individual or group behaviours that collectively impact on society. The greatest advances toward defining the social product has been made by Kotler and Roberto (1989). These authors describe the social product as consisting of three elements relating to behaviour implementation: an idea ( which may take the form of beliefs, attitudes or values); a practice (either one-off or on-going) and/or a tangible object. Important issues to consider in this latter definition are firstly, recognition that social marketers promote ideas as well as practices as a prelude to bringing about the behaviour change outcome. Secondly, specifying the social product as a composite of entities allows for conceptualisation of the "total" social product idea. Thus, social products take on an abstract form such as family planning which may involve changing attitudes, include an on going behaviour and/or the use of contraceptive devices, or the social product may incorporate more differentiated products such as anti-racism. Thirdly, whilst included as a dimension of the social product, the primary function of the tangible component product base is to augment the core product, that is, a change in behaviour. For example, a physical product is not required to stop smoking, however a physical product such as nicotine patches may make the idea more concrete as well as enhance the probability for a successful attempt at self-behaviour change. While each of above mentioned interpretations of the social product differ in orientation (ie. conception, outcome or implementation foci), there is general agreement that the social product is the outcome of the campaign ie. a change in behaviour. These changes of behaviour may involve starting a new behaviour such as donating blood; stopping a behaviour such as giving up smoking, alcohol or drugs; or switching a behaviour such as dietary alterations or driving slower. More importantly, the critical unifying element of these social product interpretations is that the social product transcends the tangible and even goes beyond the intangible service product to the conceptual idea product. Thus, the social product not only differs from physical and service products by the degree of intangibility, but also by the nature of the intangibility which is based on the combination and integration of elements as articulated by Kotler and Roberto (1989). Product Entity Model 2 The consumer benefit concept recognises that the core product surrounding most product entities will always be intangible and to a large extent conceptual. For example, consumers buy "hope" not lip stick, "quarter inch holes" not quarter inch drills or "time critical transport" rather than air or car transport. However, one does not buy skin cancer protection, drug prevention or environmentalism, rather these are attitudes or values which are then transferred into behaviours. Thus, while the core product surrounding most products can be related to a conceptual idea, it is the degree and nature of the intangibility dominating the articulated product entity (ie. physical/ service/social) that helps to unravel the "fuzzy" social product. While it has long been acknowledged that service dominant entities differ from physical good dominant entities, further consideration needs to be given to how "idea/practice" dominant entities differ from these other well articulated product entities. The complexity surrounding the social product can be more clearly understood when the articulated product entities (ie. physical goods, services and social idea/practices) are examined in a tangible versus intangible versus conceptual framework. Figure 1 illustrates the three primary product types physical, service and social product - according to their dominant characteristics (as shown by the circle) and by the characteristics that facilitate the delivery and consumption of the articulated product (as shown by the arrows). Figure 1: Product entities Physical Product Service Product Social Product Tangible dominant Tangible & intangible dominant Conceptual idea leading to practice Intangibles Intangibles and tangibles Tangibles and intangibles Intangible Conceptual Tangible Evolutionary Scale The predominant nature of the physical 'good' product is as a tangible object, device or thing (Berry 1980) supported largely by abstract, intangible associations such as image, branding and advertising which add value to the core offering and serve to differentiate the product among offerings. For example, the dominant nature of the product Coca Cola is tangible, yet the product is clearly differentiated in the marketplace by linking abstract image associations (visual, verbal) to the physical item. The dominating characteristic of services, in general, can be considered a mixture of tangible and intangible elements which are facilitated by the service delivery system that assists to not only create the product but also deliver it simultaneously to the consumer, with the consumer being actively involved in the process. In comparison to a physical good, a service can be considered a "performance" rather than a "thing" (Lovelock et al 1998). The service product is intrinsically tied to elements that facilitate the delivery of the service (such as billing, order 3 taking, payment or information provision processes), as well as supporting services which add value to the core service offering and serve to differentiate one service provider from another (such as problem solving procedures, providing hospitality, or safekeeping possessions) (Lovelock et al 1998). The consumer benefit concept for the service cannot exist without the delivery system and the specification of the system is as much the specification of the product (Bateson 1995). Extending beyond physical products and services, the social product is a purely conceptual entity (an idea, attitude, value or behaviour) moderated primarily through peripheral cues comprised of tangible and intangible elements as a means to facilitate behaviour change. Thus, the social product incorporates many of the aspects of services (eg. counseling services, telephone help lines), physical good products (eg. nicotine patches) and advertising and branding techniques (eg. "Quit Smoking") employed to both deliver and tangibilise the social product in a framework the consumer is able to comprehend. The web of confusion surrounding the legitimacy of social marketing as a sub-discipline of marketing stems, in part, from the naïve assumption that the expansion of marketing's domain resulted only in the addition of products of increasing intangibility (Whyte 1985). More importantly, the inclusion of psychological entities, such as ideas, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours as possible marketing products involved not only an elongation in the degree of product intangibility but also involved a reconceptualisation of the nature of product entities. Modeling product types according to their discrete characteristics clearly identifies the dominance of tangible, intangible or conceptual elements. From this perspective, the various product entities can be viewed as existing on a continuum which includes not only tangible and intangible dimensions but also the newly articulated "conceptual" dimension (see Figure 1). While all products involve to some degree a combination of characteristics, what differentiates one type of product (physical/service/social) from another is the relative emphasis on tangible versus intangible versus conceptual elements. While intuitively understood, this element of product entities has been seldom articulated. This reconceptualisation of the nature of product entities to include a "conceptual" dimension favours the legitimacy of social marketing as being a clear and needed variant of the traditional marketing discipline. Managing the social product Development and management of the marketing process for the social product calls for identification of the unique differences that distinguish the "idea" product from physical goods and service products. Some of these differences are described below and need to be developed in future work. In a commercial marketing situation, the marketing methods generally employed are designed for situations in which benefits to the consumer for choosing an advertised product or service clearly outweigh the costs (Rangan et al 1996). Purchasing an automobile with a certain set of features is a clear cut proposition with a certain set of features. With social marketing, however, the products are not exactly fast moving or high in demand. Moreover the demand situation may be non-existent (eg: family planning among certain religious groups) or negative (eg driving slower or giving up smoking/drugs). More importantly, the benefits of a social marketing campaign are not always so concrete as in commercial marketing situations. Often the benefits are invisible for example child inoculation where success means that nothing happened ie. no measles or polio which makes it difficult for the target audience to see a connection between the recommended behaviour and specific outcomes. In addition, it 4 may be difficult to make distinctions as to who are the primary beneficiaries of any given social change program. A program designed to encourage women to be tested for cervical cancer clearly benefits individuals. A smoking prevention program benefits not only the individuals to whom the campaign is directed, but also health insurance premiums and society. With a recycling program the primary beneficiary is the community and society on the whole, rather than an immediate outcome return to the individual. Traditional commercial marketing generally involves situations where product demand is not only relatively high, but also positive in nature. On the other hand, social change often involves altering people's core attitudes and beliefs as a prelude to changing behaviour to create product demand. Consider the issue of skin cancer prevention in Australia. Changing behaviour in relation to the sun involved both education as to the long term consequences of sun abuse as well as changing the fundamental belief that "brown is beautiful". Furthermore, the Cancer Council's "Slip (on a tee-shirt), Slop (on a hat), Slap (on sunscreen)" media campaign provided a behavioural solution to preventing skin cancer easily adopted by consumers. However, in the situation of government regulating of population growth in countries where children are an integral element of family support and the social system, or where family planning is considered an unnatural act, the ability to change attitudes, beliefs and behaviours is both difficult and complex. Clearly, social marketing takes the macro-marketing perspective with the objective of any social marketing campaign being to achieve broader social benefits in contrast with the commercial marketing approach which takes a micro-marketing firm-consumer exchange perspective. In the process of achieving social change, social marketing activities are built around applying and adapting knowledge gained from business practices to develop campaign strategies targeting specific segments within communities. However, in developing the campaign consideration needs to given to the nature of the change program and the marketing problem. Where the change of behaviour is relatively small compared to the benefits, the marketing situation may be simply persuading consumers to purchase products or services currently available (eg: pap smears). On the other hand, social change campaigns may involve considerable changes in attitudes and behaviours involve a more complex marketing strategy involving diffusion of ideas among the community as a precursor to attitude and behavioural change. Conclusion The past two decades have been about the marketing of social marketing. To further deepen the domain, our thinking about social marketing needs conceptual clarity if greater analytical rigor is to be bought to the area. The "fuzzy" social product can be related back to one structural difference - expanding beyond intangibility to include the conceptual. This paper has attempted to explore the idea product, as distinct from those of goods and services. Recognition that idea-dominant entities differ from good or service entities allows consideration of other distinctions which have been intuitively understood, but seldom articulated. References AMA board approves new marketing definition. (9185, March 1). Marketing News, p.1 Andreasen, A. (1995), Marketing Social Change: Changing Behaviour to Promote Health, Social Development, and the Environment, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco 5 Bagozzi, R.P. (1975), "Marketing as Exchange", Journal of Marketing, 39, 32-39. Bateson, J.E.G. (1995), Managing Services, Marketing, Dryden, Orlando USA Berry, L. (1980), "Services Marketing is Different", Business Fine, S.H. (1981), The Marketing of Ideas and Social Issues, Praeger, New York. Goldberg, M., M. Fishbein, and S.E. Middlestadt (1997), Social Marketing: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey Kotler, P. (1972), "A generic Concept of Marketing" Journal of Marketing, 36 (2), 46-54 ---- and S.J. Levy (1969), "Broadening the Concept of Marketing", Journal of Marketing, 33, 10-15 ---- and E.L. Roberto (1989), Social Marketing: Strategies for Changing Public Behaviour, The Free Press, New York Levitt, T.H. (1960), "Marketing Myopia", Harvard Business Review, 38, 45-46 ---- (1981), "Marketing Intangible Products and Product Intangibles", Harvard Business Review, 59: 94-102. Lovelock, C.H. (1979), "Theoretical contributions from Services and Nonbusiness Marketing", Conceptual and Theoretical Developments in Marketing, 147-165 ----, P.G. Patterson and R.H. Walker (1998), Services Marketing: Australia and New Zealand, Prentice Hall, Australia Rangan, V.K., S Karim and S.K. Sandberg (1996), "Do Better at Doing Good", Harvard Business Review, May-June, 42-54 Whyte, J. (1985), "Organisation, Person and Idea Marketing Exchanges", The Quarterly Review of Marketing, Winter, 25-30. 6