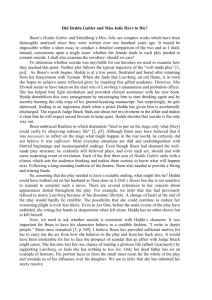

Hedda Gabler - WordPress.com

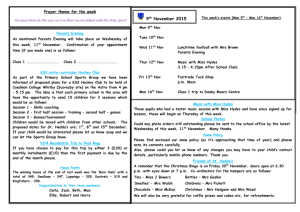

advertisement