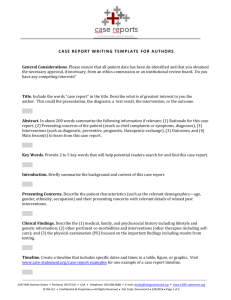

A diagnostic model PAPER

advertisement