Appreciating Value

advertisement

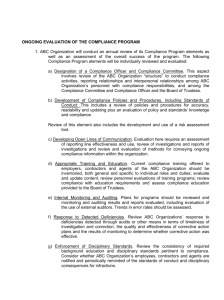

Appreciating Value Issue 5 November 2009 Contents Welcome to Issue 5 of Appreciating Value. As the Australian economy emerges from the downturn our thoughts turn to profiting from the next growth cycle. In this issue the team investigates how Management can best analyse profitable growth opportunities. A key lesson from the Global Financial Crisis is that a project’s risk must be priced effectively when considering opportunities to deploy capital. The resurgence of Value Based Management and particularly Economic Profit is considered in our first article. Value based management – Simple truth 1–2 Valuation models – just a point in time, or performance enhancing as well? 3–4 Learning the lessons of ABC 5–7 Economics in brief A ‘macro’ point of view and key metrics The second article investigates how the humble DCF can be an effective Management tool to enhance a company’s performance. ASX Industry Market Multiples As of 9 November 2009 Lastly, we introduce the first of our case studies – in this issue we take a look back at ABC Learning Centres and the lessons that can be learnt by all from its demise. As always, we welcome feedback and suggestions from our readers. If you have any comments or would like us to cover a particular topic in future, please contact us at: appreciatingvalue@au.pwc.com Mark Reading Editor About PwC Corporate Value Advisory 8–9 10 11 Value based management – Simple truth? The global financial crisis has caused Boards and Executive Teams to keep a closer eye on the capital that is employed in the business. Unsurprisingly, various forms of Value Based Management are gaining in popularity again. Time to revisit an old friend: Economic Profit. The GFC has reminded us of two fundamental business principles: “ This disconnect between ‘value’ and ‘accounting’ has left companies puzzled with poor shareholder returns while accounting profits have been improved. ” a. Capital both in the form of equity and debt is the origin of any business activity; and b. Capital commands a level of return appropriate to compensate for the level of risk to which it is exposed. Both principles are reflected in the concept of the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). This cost of capital rate is a blended rate of both the cost of debt and the cost of equity. It is widely accepted and has been used in practice for decades when it comes to decision making: the WACC is the discount rate in free cash flow valuations. However, the cost of equity as reflected in the WACC is an opportunity cost and therefore can’t be found in Income Statements. This disconnect between ‘value’ and ‘accounting’ has left companies puzzled with poor shareholder returns while accounting profits have been improved. At times this disconnect can become a threat to a company’s existence when impairments force the ‘value’ perspective back into the equation. Impairments can lead to debt covenant violations or generally reduced creditworthiness and difficulties in refinancing maturing debt. Let’s have a look at a prominent example: $ million NPAT The difference between the two graphs lies in the opportunity cost of equity. NPAT is already reflective of the cost of debt (interest), but it ignores the opportunity cost of equity. Economic Profit = NPAT – Opportunity Cost of Equity This is the one big thing about Value Based Management and metrics like Economic Profit or Economic Value Added (EVA): they go beyond accounting in that they consider the opportunity cost of equity. This is a small extra step and simple enough to calculate but it has far reaching consequences for corporate objectives, strategy development, decision making, performance measurement, balanced scorecards and driver trees, and very importantly, incentive remuneration. Profit metrics ignorant of the opportunity cost of equity (e.g. EBIT, NPAT, EPS…) should not be part of executive incentive plans, at least not if you want to properly align shareholder and management interests. The perception that Economic Profit is a complex matter and not easily understood by general management has its origin in the past. Previously, numerous adjustments to the accounting numbers were applied to measure performance more accurately. Firstly, this is not a defining element or specific to Economic Profit (e.g. analysts would calculate an ‘underlying’ EBIT, too). Secondly, accounting has come a long way over the past decades towards a true and fair view. Today, most companies choose to keep it as simple as possible, and don’t apply any adjustments at all. Let’s have a glimpse at the power of the framework in a management context. 200 150 100 50 0 Economic Profit is usually calculated as: Economic Profit = NOPAT – (WACC x Capital Employed) 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Economic Profit $ million This is the data for ABC Learning Centres (ABC) and of course it all ended in tears. But what actually is it that the graphs reveal? 50 0 -50 -100 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 In this case Net Operating Profit after Tax (NOPAT) can be defined as NPAT without interest expenses. Interest expenses together with the opportunity cost of equity are captured by the WACC applied to the capital employed (equity plus debt or total assets less non interest bearing liabilities). With Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) defined as NOPAT/ Capital Employed, the above equation can be restated as Economic Profit = (ROCE – WACC) x Capital Employed Table 1 Appreciating Value 1 What would you like to change ? Value based management – Simple truth? Excess Return (ROCE – WACC) is a strategic measure of competitive advantage or attractive markets. Capital Employed puts the advantage to a dollar scale. The two factors can be mapped out on the following graph: The Iso EP Map is useful to understand the historic journey of a company, compare performance and strategic direction to peers, or map the strategic plan going forward. It was originally developed for holding companies and portfolio management purposes. Iso EP Map 10.0% ” 7.5% growth EP = 150 5.0% 2 2.5% profitability Excess Return (ROCE – WACC) “ Economic Profit is where strategy meets numbers. EP = 200 3 EP = 100 EP = 50 Economic Profit is where strategy meets numbers. Hence, a successful implementation and application usually takes a CFO with a strategic view, a CEO who is not ignorant of the numbers or a good cooperation between the two. 0.0% EP = -50 -2.5% EP = -100 -5.0% EP = -150 -7.5% 1 consolidation EP = -200 -10.0% 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 Capital Employed Economic Profit multiplies profitability with growth, solves the trade-off and provides a single objective - improve EP! Each dot on the Iso EP Map represents Economic Profit as a product of Excess Return and Capital Employed. The same level of Economic Profit can be achieved through different combinations of Excess Return and Capital Employed. For example, an EP of $50 can be achieved through an Excess Return of 10% on Capital Employed of $500 or 5% on Capital Employed of $1,000. The graph above shows Economic Profit levels as iso-lines in steps of $50. The blue arrows indicate directions to improve EP and can be categorised in three general directions: 1. Consolidation • Optimise net working capital • Dispose of non-core or unproductive assets 2. Profitability • Cost reduction • Revenue enhancement 3. Growth • Leverage existing core competencies into adjacencies • Geography, products & services, value chain coverage, etc Guido Gadomsky Perth Appreciating Value 2 What would you like to change ? “ If the valuation model was so important in making the initial decision why not use it going forward to measure the performance of the business? ” Valuation models – just a point in time, or performance enhancing as well? Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis is one of the most commonly used approaches to estimating the intrinsic value of a business. Part of its appeal is that it draws together consideration of competitive advantage, operations, capital requirements, and the opportunity cost of capital. That’s why when considering whether to buy, or invest in, a business many people will turn to a DCF approach. However, after the acquisition the DCF model’s prominence often fades, and performance reporting turns to accounting measures. If the valuation model was so important in making the initial decision why not use it going forward to measure the performance of the business? At first thought the initial objection to this question will be that the DCF model provided a view of the business only at a point in time. However, there is a relatively simple method of using the DCF model to track performance, thereby creating a measure which provides insight and better alignment to investors. Consider the simplified company DCF shown in Figure 1 which we’ll assume was prepared at the commencement of 2010. For the purpose of this simple example the forecast horizon is only 5 years, but in practice this approach can be used with a longer forecast horizon and a terminal value. This makes it suitable for the performance measurement of indefinite life assets, like companies. Note that in Figure 1 the forecast free cash flows have been discounted with a rate of 10% to yield a present value of $500 (insert billion if you like to think big). Start of year Year 2F 2011 Year 3F 2012 Year 4F 2013 Year 5F 2014 Forecast free cash flow $120 $126 $133 $139 $146 Present value factor 0.91 0.83 0.75 0.68 0.62 Present value of forecast $110 $105 $100 $95 $91 Total present value of forecast $500 End of year Actual 2010 Year 1F 2011 Year 2F 2012 Year 3F 2013 Year 4F 2014 Forecast free cash flow $120 $138 $133 $139 $146 Present value factor 1.00 0.91 0.83 0.75 0.68 Present value of forecast $120 $125 $110 $105 $100 Total present value of forecast $440 Forecast Figure 2 The DCF at the end of the year in Figure 2 changes in two other respects, that is the year 2010 has become “Actual”, and since we have moved forward in time the present value factors have been adjusted accordingly. The present value of the remaining cash flows is now $440. The company’s performance for the year can now be judged by comparing the end of year to the start of the year, as shown below in Figure 3. Calculation of performance Cost of Capital 10% A Value as at end of year $440 –B Value as at start of year $500 =C Change in Value ($60) +D Actual cash flow realised during year $120 =E Total Return $60 –F Expected Return $50 Forecast =G New Value Created $10 Year 1F Year 2F Year 3F Year 4F Year 5F 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Figure 3 Forecast free cash flow $120 $126 $133 $139 $146 Present value factor 0.91 0.83 0.75 0.68 0.62 Present value of forecast $110 $105 $100 $95 $91 Total present value of forecast $500 Figure 1 In the example let’s now move ourselves forward 12 months to the end of 2010 (wow, what a year!). We can now compare the original forecast to the updated version at the end of the year, as shown in Figure 2. Let’s suppose that at the end of 2010 the business has exactly performed as forecast, with the exception that the forecast free cash flow in 2011 has now increased from $126 to $138 (perhaps due to anticipated cost saving, or additional revenue). Appreciating Value 3 Forecast Year 1F 2010 Start of year The first step is to calculate the change in the value of the forecast, yielding a negative change in value of $60 (i.e. in Figure 3, A-B=C). To this we now add the $120 cash actually realised during the year, so the total return was $60 (i.e. C+D=E). We compare this to investor expectations, the ‘Expected Return’, by multiplying the starting value of $500 by the 10% cost of capital. New Value Created is now $60 – $50 = $10. This $10 is significant because it is value which has been created over and above the expectations of investors, as quantified in the 10% cost of capital. Had the 2011 forecast free cash flow not increased the result would have been zero, signifying that investors’ expectations had been met exactly. Of course the opposite could also have occurred, with a negative result showing value had been lost. What would you like to change ? Valuation models – just a point in time, or performance enhancing as well? To continue to use this approach the management team merely add a year to the end of their forecast, perhaps as part of an annual planning process, and ‘lock it in’ for the same comparison in 12 months time. Other time frames, such as quarterly or semiannually, are also feasible. “ This approach gets management focused on the value of the business using the same approach that investors use. ” But what’s to stop someone from arbitrarily increasing the forecast, in order to make their performance look good? Well, there are two main reasons: 1. Behaviour like that becomes a ‘one shot game’ as the ending value becomes the new starting value used to judge the following year’s performance, i.e. they’ve raised the subsequent benchmark. As a further deterrent, if this measure is linked to an incentive scheme then deferral of payments would be recommended. 2. The time value of money means that to spuriously affect performance the changes either need to be close in time to the present or very large, either of which would be noticeable to directors and other managers. What would you need to get started? 1. Develop a robust corporate value model which you believe captures the true underlying economic drivers of the business. 2. Build the use of the value model and this measure into the firm’s planning and management processes. This should include some training. 3. Include people from other functional teams, not just finance, as they can make valuable contributions to discerning the core economic drivers of the business. 4. Consider the use of the measure in your company’s dialogue with investors. Building and enhancing these capabilities ensures that management’s efforts are more directly linked to value creation. The more people there are looking at the business through a value lens, the more likely it is that shareholders will be delighted. This approach gets management focused on the value of the business using the same approach that investors use. Surely that’s an important outcome since managers are custodians of capital and trying to deliver returns at least equal to expected returns. Other benefits include: 1. As for traditional measures there is still recognition of current performance, via ‘actual cash flows realised during year’. 2. But this measure is also forward looking. This is a key distinction given that managers are paid to worry about the future, not what’s just happened. 3. Although this approach could be used for any business, public or private, it will have particular attraction for management teams focused on making long term strategic decisions. Are you a manager making decisions which will have impact far into the future? 4. This approach can also be applied to large capital investments using the Net Present Value (NPV) model as the basis and following the same logic. James O’Brien Sydney Appreciating Value 4 What would you like to change ? Learning the lessons of ABC By understanding value, boards and managers can sidestep the issues that brought one of the fastest growing companies in Australia to its knees. “ To uncover some answers … we opened our toolbox of value tools and analysed publically available information … to see if we could find anything that might provide a hint of what was to follow. ” While the financial press has been full of stories of corporate collapse, the collapse of ABC Learning has been one of the more emotional. Widespread reporting of parents concerned by the impending closure of their ABC Learning Centre has focused community attention on what went wrong with this erstwhile darling of corporate Australia. Not only have children, parents, shareholders and creditors been affected but the founders also saw a concerted run on their (highly leveraged) holdings by short sellers, leading to a significant loss of personal wealth. Were there any early warning signs that senior managers and boards could look to so they short circuit these types of calamitous outcomes in their own businesses? To uncover some answers, we travelled back in time – to a time when ABC Learning was at its zenith, in 2006. We opened our toolbox of value tools and analysed publically available information from 2006 and 2007 to see if we could find anything that might provide a hint of what was to follow. Clearly, the context of the rapid growth and share price appreciation that ABC Learning experienced should not be ignored; it is often easy to pinpoint issues in hindsight. However, disciplined financial management is like driving in that it requires us all to look for potential accidents, even when the traffic is running smoothly. Accordingly, we’ve unapologetically sought to find a glimpse of the oil on ABC Learning’s road even as it was racing ahead. A brief primer on ABC Learning ABC Learning operated childcare centres or nurseries in Australia, NZ, the UK and the USA, as well as some schools in the USA. By 2007, it had revenues of almost $1.8 billion, across almost 1,200 outlets in Australia and New Zealand and more than 1,000 in the Northern Hemisphere, employing thousands. It grew from annual revenues of $40 million in 2003 – a phenomenal growth trajectory by any standards. Chart 1 plots the trend of revenue growth and share price over this period. Appreciating Value 5 Chart 1: Revenue and average share price 20032008 ABC’s growth came from three sources; most significantly acquisitions, green-field developments and organic growth. Because of the sensitivity of childcare operations, regulation and government funding were substantial considerations in how it ran its business, with increased funding of childcare places being a substantial driver of organic growth. Revenue was largely dictated by the number of places filled in the centres and costs were predominantly labour and premises, the number and condition of which were largely regulated, making the costs fixed within quite large ranges of child numbers. Margin expansion was to some extent achievable by initiatives such as tailoring child place mix, increasing administrative leverage, developing procurement/property efficiencies and promoting wage restraint. From a market perspective, ABC Learning experienced dizzying growth in value touching a high of $8.80 per share, which placed its founders in many lists of Australia’s most wealthy. Even into 2008, ABC Learning continued to grow. Unfortunately, it didn’t last. Short sellers targeted the stock leading to precipitous declines in value, creating nervousness around the company’s survival. On 6th November 2008, matters came to a head with the group being placed into voluntary administration. ABC Learning was not a particularly complex business, nor did it engage in extensive financial engineering. Essentially, it was a good business that got itself into trouble. The key question is, could trouble have been spotted earlier? What would you like to change ? Learning the lessons of ABC In using our value toolkit, we took into account three perspectives to see what warnings were available – a market perspective, an accounting perspective and a value governance perspective. “ Economic profitability was negative in both periods we reviewed. This implied that the business was not generating the returns that justified the capital invested in it. ” We have not adjusted for any of the restatements that occurred in 2008. To do so would distort the information available in 2007, but clearly if the restatements had been included, the picture would not have been better than what is explored below. A market perspective Firstly, the market perspective provided some insight. We took four key measures from our corporate value model that summarises the way the market looks at a company. The four measures we chose were: the z-score, volatility, economic profitability and economic leverage. The z-score is a credit scoring model, which estimates the risk of credit default in a similar way to credit markets. Volatility is a measure of the variability in share price, which provides a market-based measure of uncertainty of value. Economic profitability compares the return on capital with the cost of capital, which is an indicator of capital efficiency. Economic leverage highlights the degree to which the business value is debt funded. ABC Learning’s scores in the two years were studied were as follows: Measure 2007 Z-score 1 -0.4 2006 5.1 Volatility 2 33% 29% Economic profit % 3 -3% -4% Economic leverage % 4 43% 4% In 2007, ABC’s z-score and economic leverage took a battering, largely as a result of substantially debt funded offshore acquisitions. The high degree of debt funding was exacerbated by the currency and short tenor of funding. This left ABC highly exposed to refinancing risk and with the added leverage implied by margin loans (as signalled by unanticipated disposals of management owned shares) made the company highly exposed to the eventual short-selling raid on the shares. From where we sit today, it can only be speculated about the rationale for the aggressive financing of the US acquisition that generated this exposure, and indeed the company sought to reduce this risk in 2008, as discussed opposite. Appreciating Value 6 Volatility in the two periods increased slightly, but ABC Learning only just made it into the top half of the ASX 300 in terms of observed risk. This measure became more of a problem for the company in 2008 but in this period of ABC’s life did not highlight major challenges. However, it was significant to note that the share price trajectory flattened and started to decline in this period, implying a perception that more downside risk existed than previously. Economic profitability was negative in both periods we reviewed. This implied that the business was not generating the returns that justified the capital invested in it. On its face, this would be of some concern, but against the background of extremely rapid growth this may have been a timing issue of when full year earnings were attributable against capital invested. During the period under review, this wouldn’t have set an alarm sounding, but it would have remained an area to watch for the board and senior managers. Accounting indicators Accounting indicators also provided some warnings during 2006 and 2007. We looked at three key indicators – EBIT interest cover which is a measure of the buffer that exists for servicing of debt holders, the current ratio, which highlights a company’s liquidity, and free cash flow as a percentage of revenue, which reveals how much of the company’s revenue is converted to cash. On the first two measures, the aggressive offshore acquisition financing plan made ABC Learning appear much riskier than it had in the past. In fact, the second measure, the current ratio was an immediate indicator of either an impending liquidity crisis or major refinancing risk. The company did notice this risk, and early in the new financial year conducted a major refinancing, with a substantial equity raising and extending the term of debt facilities. However, with hindsight, this refinancing was not enough to stem the tide that was turning for ABC Learning. In terms of free cash flow generation, very little of ABC Learning’s stellar revenue growth was being converted to cash. This raises questions about whether the level of growth was sustainable or whether ABC Learning was in fact over extending in its quest for rapid growth. 2007 2006 Interest cover 5 Measure 3 5 Current ratio 6 0.25 2 FCF % of revenue 7 1% -4% What would you like to change ? Learning the lessons of ABC Value governance From a value governance perspective, we considered four aspects. “ ABC was on a growth binge, fuelled in part by its systems of governance pertaining to value. The growth binge failed to fully take account of the capital consumed or the dramatic risk profile that the sources of that capital created for the group. ” First, we looked at the incentive plan in place for senior management. We noted that this was largely driven by increases in EBITDA. Inherent in the structure of this incentive plan was that the capital invested in delivering this EBITDA growth was not accounted for. This created a structural deficiency in accountability for capital employed, a fundamental aspect of value governance. In 2008, the company sought to address this shortcoming, if belatedly. Another issue of value governance is the incentives implied by related party transactions with members of the board. The impact of any board member deriving related party fees as a result of capital raisings, property transactions and acquisitions is a relevant consideration for investors. Without access to non-public information relating to these transactions, of course, no conclusions can be drawn around the nature of the advice provided. However, on its face, any financially sophisticated member of a board who may have an incentive, through related party transactions, to accelerate growth velocity at rates that may be difficult to sustain is a sign of potentially increased risk for investors. ABC Learning’s investor base provided interesting value governance challenges. Despite the stellar growth described above, ABC Learning’s analyst following remained relatively limited, the institutional investor base remained narrow and general shareholdings remained closely held. These challenges may have muted the feedback of the market to the company, and almost certainly exacerbated valuation downside when positive momentum waned. The final issue of value governance was around disclosure of quality of earnings. By any measure, ABC’s growth was stellar. It also engaged in some innovative property finance transactions. In circumstances like this, it was difficult to truly tell what the underlying earnings from operating its centres were – there were challenges around the clarity of presentation of revenue and margins of franchised centres, half periods of earnings from new acquisitions, restructuring costs, and one-off profits of centre redevelopment. Given the complexity of these phenomena, greater transparency would have provided investors and creditors much more certainty and perhaps alleviated many concerns that were emerging. Allied with this opacity, the earnings restatements that emerged in 2008, with the appointment of a new auditor heaped more market scepticism on the quality of earnings. Furthermore, the lack of continuity in the CFO over this period may have restricted the company’s ability to have necessary market dialogue to develop clarity in earnings reportage. Conclusions Boiling down all of the above analysis, there were warning signs about ABC Learning even in its heyday. Fundamentally, ABC was on a growth binge, fuelled in part by its systems of governance pertaining to value. The growth binge failed to fully take account of the capital consumed or the dramatic risk profile that the sources of that capital created for the group. The good news is that lessons can be drawn from this sad outcome which will enable boards and senior managers to avoid or prevent the difficulties that ABC Learning has been through in the last year or two. To summarise these lessons: • Understand how debt and equity markets view your business, particularly in terms of your risk profile • Check out what your value governance says about your company – − what behaviours are incentives likely to generate, − what could related party transactions say about the likely stance of the board, − how does your investor base influence value outcomes and − how transparent are your reported earnings. These sound like simple lessons, but they are lessons that are very costly if ignored. Richard J Stewart Sydney Appreciating Value 7 What would you like to change ? Economics in brief A ‘macro’ point of view The global economy is growing again after contracting sharply late last year and in the early part of 2009. The risk aversion that was so evident earlier in the year, particularly in financial markets, has abated and confidence is gradually returning. GDP growth would have been stronger had exports not been tempered by the sharp drop in global prices for agriculture commodities and lower coal and iron ore contract prices which came into effect during the quarter. Chart 1: Quarter-on-quarter growth rates “ The risk aversion that was so evident earlier in the year, particularly in financial markets, has abated and confidence is gradually returning. ” Interestingly, this turn around in global economic fortunes has not been driven by the traditional economic powerhouses – the USA and the EU – but by the emerging Asian economies. The Asian region’s financial systems have not experienced the same dislocation as elsewhere in part due to the substantial reforms which resulted from the turmoil of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-98. The Asian economies are also benefiting from a recovery in domestic demand, as these traditionally high saving populations are encouraged to increase consumption. Growth in China and India has been particularly strong. Economic conditions in Australia have also been stronger than expected. In contrast to other developed economies, the Australian economy is estimated to have expanded, albeit modestly, over the first half of the year and recent data suggest that this expansion has continued into the second half. Confidence has improved and spending has been supported by stimulatory settings for both monetary and fiscal policy. The challenge that now faces those at the controls of fiscal and monetary policy is to determine an appropriate pace to roll back the expansionary settings of both forms of stimulus without stymieing the recovery of the Australian economy. GDP Consumers Gov Investment Exports Imports 2% 0% -2% -4% -6% -8% 2008 Q3 2008 Q4 2009 Q1 2009 Q2 Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Stimulus measures drive the economy The Government cash handouts continue to prop up consumer confidence. This was reflected in the performance of industries with direct exposure to discretionary spending. Retail trade grew by 1.7% q-o-q, restaurants and cafes by 0.9% q-o-q and recreational services by 3.7% q-o-q, its strongest growth since Q3 2007. Consumer confidence has also hit its highest level since December 2007 with the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment reaching 119.3 in September 2009 (see chart 2). Chart 2: Household consumption and growing consumer confidence Household Consumption (LHS) 1.6 120.0 Consumer Confidence Index (RHS) 1.2 Given that the Australian economy is operating with less spare capacity than earlier thought likely, and the outlook for the next few years has improved, the Reserve Bank Board has elected to lessen the degree of monetary stimulus in place by increasing the cash rate by 25 basis points at both its October and November meetings. The cash rate is still deemed to be at low levels and it is likely the Board will continue to raise rates as the economic recovery strengthens towards a neutral position (thought to be a cash rate of around 5.0%-6.0%). The buoyant Australian economy The Australian economy expanded by 0.6% in Q2 2009 relative to Q2 2008 (see Chart 1 below). This is the second consecutive quarter of growth after contracting by 0.6% quarter-onquarter during Q4 2008. Domestic growth, both household and business, was led by the Australian Government’s fiscal stimulus flowing through the economy. Household spending was up 0.8% q-o-q while business investment grew 1.9% q-o-q. Appreciating Value 8 100.0 0.8 80.0 0.4 0.0 60.0 Dec-07 Mar-08 Jun-08 Sep-08 Dec-08 Mar-09 Jun-09 Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and Westpac Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment Index Companies are still showing caution, choosing to run down inventories as opposed to re-stock in order to meet the surprisingly strong, stimulus driven, consumer demand. Despite this caution, private business investment rose by 1.9% q-o-q as companies took advantage of the historically low interest rates and the Government’s tax incentives designed to bring forward the purchase of critical machinery and equipment. The Reserve Bank is now watching carefully for inflationary pressures resulting from this fiscal stimulus, with rates having started their rise from these historically low levels back towards the long term norm of 5.0% to 6.0%. What would you like to change ? Economics in brief A ‘macro’ point of view Treading lightly along the road to recovery “ While the cash hand outs, tax offsets to business and infrastructure spending have placed the budget into deficit, these measures can be considered one off, or temporary in nature. ” It appears that the Australian economy has dodged the worst of the global recession and stabilised, setting the stage for an imminent recovery. However, there are still obstacles on the road to recovery, one of which is the successful winding back of the emergency stimulus measures. While the cash hand outs, tax offsets to business and infrastructure spending have placed the budget into deficit, these measures can be considered one off, or temporary in nature. They appear to have supported the intended sectors during the global financial crisis without fundamentally changing or distorting the markets in which these sectors operate. These measures therefore pose less risk to destabilising areas of the economy as they are wound back. By contrast, the boost to the first home buyers’ grant and Government bank guarantee have both had a structural impact upon the markets they were designed to support. The demand generated by the boost to the first home buyers’ grant has shored up Australian housing prices during the crisis. Key metrics Indicator So while Australian prices matched the strong growth shown in the US and UK in the period leading up to the crisis, they appear to have avoided the sharp drop which has been witnessed overseas (see chart 3). The Government has signalled the gradual withdrawal of this measure: however the short term impact on house prices and longer term impact on housing affordability remain to be seen. Chart 3: House-prices % change in real terms for 2001-2006 and 2007-Q2 2009 65% 45% 25% 5% -15% -35% Australia Britain 2001 - 2006 US 2007 - 2009 (Q2) Source: , Standard & Poor’s and US Case Shiller Index The government bank guarantee has also influenced the structure of the Australian banking sector, leading to the consolidation of the ‘big four’ banks’ positions as smaller institutions face higher funding costs and non bank lenders struggle to access capital. However, the strength of the ‘big four’ has been one of the reasons behind the relative stability of Australia’s financial markets during the crisis. Hence the withdrawal of this guarantee needs to consider not only the competitive forces within the Australian market place, but also the nature and time span of similar such overseas guarantees so as not to weaken the position of Australian banks within the global market. 2007 2008 2009f 2010f GDP growth 4.0 2.4 0.4 1.4 Consumer spending 4.4 2.6 1.7 1.7 Government spending 2.4 4.1 2.6 2.3 Real growth (annual % change) Investment 9.5 9.6 -4.9 -3.2 Export Imports 3.3 11.8 3.8 11.3 1.4 -11.3 3.4 2.0 2.3 4.4 1.5 2.2 6.75 4.25 3.50 * ↑ Inflation CPI (annual % change, average) Interest rates (%) Base interest rate (EOP) Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics; Reserve Bank of Australia; PricewaterhouseCoopers Economics’ forecasts (f) Economic analysis provided by PricewaterhouseCoopers Economics. * Rate as of 4 November 2009 is 3.50% James Liddy Sydney Appreciating Value 9 What would you like to change ? ASX Industry Market Multiples As of 9 November 2009 No. of companies EV/EBITDA Multiple P/E Multiple Automobiles and Components 11 6.3x 9.9x Consumer Durables and Apparel 26 5.7x 11.6x Consumer Services 30 8.0x 14.0x Media 34 8.3x 13.4x Retailing 33 8.1x 15.4x Industry Consumer Discretionary Consumer Staples Food and Staples Retailing 8 7.1x 20.3x 40 8.8x 16.0x 2 4.3x 10.2x 198 8.4x 13.2x 12 N/A 14.1x 141 7.9x 13.9x 9 11.5x 18.2x 85 12.4x 11.9x Healthcare Equipment and Services 66 7.2x 15.5x Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology and Life Sciences 75 5.9x 17.0x Capital Goods 97 6.0x 12.8x Commercial Services and Supplies 56 7.1x 14.8x Transportation 22 7.7x 13.6x 3 3.9x 6.4x Software and Services 65 7.1x 14.0x Technology Hardware and Equipment 28 4.2x 13.1x 568 6.5x 12.7x 25 4.9x 11.1x 26 12.6x 21.2x 1661 7.5x 11.7x Food, Beverage and Tobacco Household and Personal Products Energy Energy Financials Banks Diversified Financials Insurance Real Estate Healthcare Industrials Information Technology Semiconductors and Semiconductor Equipment Materials Materials Telecommunication Services Telecommunication Services Utilities Utilities Total Source: Data obtained from Bloomberg and Capital IQ Reported multiples are average ratios in the industry group (excluding negatives, outliers and not meaningful data) Definitions • N/A = Data is not available/applicable, • EV = Market Value of Equity plus Preferred Equity plus Minority Interests plus Book Value of Debt minus Cash • EBITDA = Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation for latest 12 months • P/E = Price to Earnings Ratio, calculated as the Market Capitalisation divided by the Net Income for the latest 12 months Casey de Souza Sydney Appreciating Value 10 Sholto Maconochie Sydney What would you like to change ? About PwC Corporate Value Advisory Understanding the concept of value is fundamental to effective decision making in business, whether raising or investing capital, driving change, managing performance or satisfying regulatory requirements. How Corporate Value Advisory can help you? Our professionals are drawn from accounting, corporate finance, tax, law, marketing, engineering and economic disciplines and include Chartered Accountants, Masters of Business Administration and those with the Chartered Financial Analyst designation. Our services include: • Value measurement – Independent value measurement and opinion to enhance management’s value position for transactions, tax and accounting; We work with our clients to improve their performance by ensuring there is rigorous analysis underpinning key management decisions. • Value enhancement – Portfolio business reviews, value based management and insights using value to deliver improved business performance; • Investment analysis – Value analytics, financial modelling and business case process to test and better inform key investment choices. Contacts Brisbane Andrew Wellington +61 (7) 3257 8816 andrew.wellington@au.pwc.com Sydney Mark Reading +61 (2) 8266 2963 mark.reading@au.pwc.com Kevin Reeves +61 (2) 8266 0617 kevin.reeves@au.pwc.com Richard Stewart +61 (2) 8266 8839 richard.stewart@au.pwc.com Alastair Pearson +61 (2) 8266 5345 alastair.pearson@au.pwc.com Perth Melbourne Roger Port Nigel Smythe +61 (8) 9238 3476 roger.port@au.pwc.com +61 (3) 8603 3970 nigel.smythe@au.pwc.com John Studley +61 (3) 8603 3770 john.w.studley@au.pwc.com Appreciating Value 11 What would you like to change ?