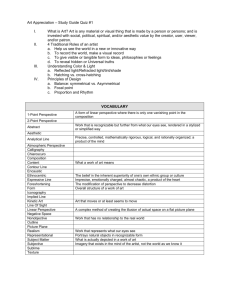

What types of styles can be associated with works of art?

advertisement