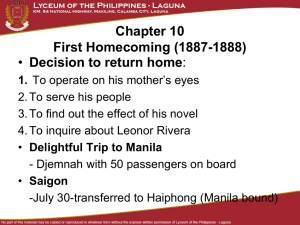

Filibustero, Rizal, and the Manilamen of the

advertisement