Appellant's Opening Brief - Electronic Privacy Information Center

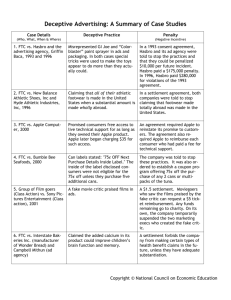

advertisement