The Effects of Matching Post-transgression Accounts to Targets

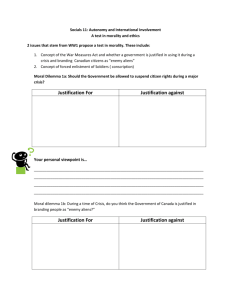

advertisement