Alcohol and Other Drug Problems Among the Homeless: Research

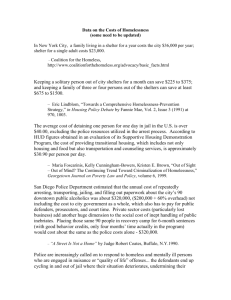

advertisement